I’m in a shabby office in Finsbury Park, north London. A sign pinned to the wall displays a countdown to the 12th of December: “30 days until socialism,” it reads. Another lists local food establishments, along with a note encouraging people to “consider spending your money in one of them, rather than a tax-dodging chain.” Aside from the wall signage, the space looks like any other office – laptops everywhere, bad carpets, the low murmur of phone conversation. Except the people who work here are not trying to sell you something. They’re here to win an election.

This is the headquarters of Momentum, the grassroots, Labour-affiliated organisation that began in 2015. Momentum, originally an amalgamation of pro-Jeremy Corbyn groups formed during his leadership campaign, is now a registered company with a governing board, full-time staff and more than 130 local groups across the country. After the December general election announcement, staff relocated to this office to accommodate the expansion from around 13 employees to 40.

Videos by VICE

Momentum campaigns for a Labour government, and is known for its impressive online presence (read: good memes), a large supporter base of young people, and really liking the policies fronted by Jeremy Corbyn. Although it functions in a similar way to other party-adjacent groups like Progress or Labour First, Momentum garnered particular attention for its critical role the snap election of 2017, helping Labour remove a Conservative majority. While the Conservatives scratched their heads, Momentum knew it had tapped into something huge.

“The story of the [2017] election is that essentially, Momentum, along with the leadership, had a very bold, positive, energetic approach to campaigning which wasn’t based on simply defending Labour seats,” Laura Parker, Momentum’s national coordinator, tells me. “We did much, much, much better than anybody thought we would, and a large part of that was down to the fact that Momentum members just thought, ‘Stuff it.’”

But to understand Momentum’s origin story, you have to go back further – to 2015. Labour, under the helm of Ed Miliband, had just lost the election to David Cameron, and a leadership election was underway. Jeremy Corbyn, an anti-nuclear weapon, jam-making backbencher was squeezed onto the ballot paper. It was a long-shot, sure, but MPs reasoned it was worth having a candidate like Corbyn in the running to allow for a full spectrum of debate. And then, something happened that no one expected. He won.

This was the first of many plot twists that the campaigners who make up Momentum would witness. Corbyn’s win led to the creation of Momentum, as well as a surge of membership to the Labour party. Jon Lansman, Adam Klug, Emma Rees and James Schneider, all involved in Corbyn’s leadership campaign, created Momentum to advocate for left-wing ideas within the Labour party, incorporate activism tactics in campaigning, and support Corbyn as leader.

When I visit Momentum, the new office is busy with workers coordinating phone banks and editing videos, so Parker and I head to the nearby Gadz Cafe. The Lebanese eatery is also known as ‘the Corbyn caff’, with pictures of the MP and ‘Vote Labour’ signs on the walls. “Probably wouldn’t take the Sunday Times here,” jokes Parker.

Momentum’s original aims were threefold: to win elections for Labour, to create a socialist Labour government, and help build a wider social movement. “I often think that Momentum is a bit like a bridge,” says Parker. “You’ve got the party issues, which of course at various points we’ve been very much aligned with [but] not necessarily, and then you’ve got the trade union movement, you’ve got climate campaigns, you’ve got renters’ unions [etc.]. And in between the two, we act as a bridge.”

This proved an effective MO during the last election. In the summer of 2017, Theresa May called a snap general election, attempting to increase her slim majority. Instead, and much to her dismay, Labour gained 32 seats, winning in safe areas like Kensington – the borough that houses Grenfell – and Portsmouth South, where the Conservatives had previously held a 12.5 percent majority. Many news outlets cited a “youthquake” as responsible for the unpredicted result, in part, caused by Momentum and Labour’s digital campaigning. While the scale of the youth turnout was questioned by the British Election Study, whose (somewhat limited) data claimed that the vote turnout of under-25s actually fell in the 2017 election, newly mobilised young people were accepted as key to Labour’s success.

“In terms of organising,” explains Parker, “social media output from Momentum was clearly much more creative and energising and entertaining than anyone else was putting out, so that got the organisation lots and lots of coverage.” Take, for example, Momentum’s parody video of the well-known First World War conscription advert, in which a child asks her father, “Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?” In Momentum’s mock-party broadcast for the Conservatives, set in “Tory Britain 2030,” a father is talking to his daughter about all the things he received from the state when he was younger, like free schools meals. “Why don’t I get any of that?” she asks. “Because,” he says proudly, “I voted for Theresa May.” The video currently has 1.2 million views.

“I think it’s the language that we spoke to people in,” continues Parkers. “The Momentum videos – they convey really pithy, deeply political messages in a way that’s interesting for people who are of a generation that, if it’s not interesting in the first three seconds, they’re going to move on.”

Momentum has taken advantage of the online political battleground. In 2017, the Conservative and Unionist Party spent £18,565,102 on Facebook adverts, compared to £11,003,980 by the Labour party. In the last three elections since the birth of social media, Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp have offered new ways to reach voters – including the controversial use of personal data to target Facebook users during the 2018 Brexit vote. The Tories have already been in hot water this year over misleading online advertisements and sponsored posts on Facebook, so far spending over £100,000 since the 29th of October. While Momentum can’t match the Conservatives on spend to artificially promote their adverts or videos, they can beat them with funnier, better and organically shared videos and memes. A recent report from the Guardian showed exactly this, listing many Momentum videos that had reached over 19 million views, compared to a measly one million for the Tories.

But it’s not just how Momentum shares its information, it’s the information itself, says Parker. “For lots of younger people, I guess they were just grabbed by finally hearing something different,” she explains. “I think that what Jeremy says appeals to young people, with £57,000 of tuition fees, debt, and no prospect of ever owning a house or actually being able to afford the rent, never mind owning anything.”

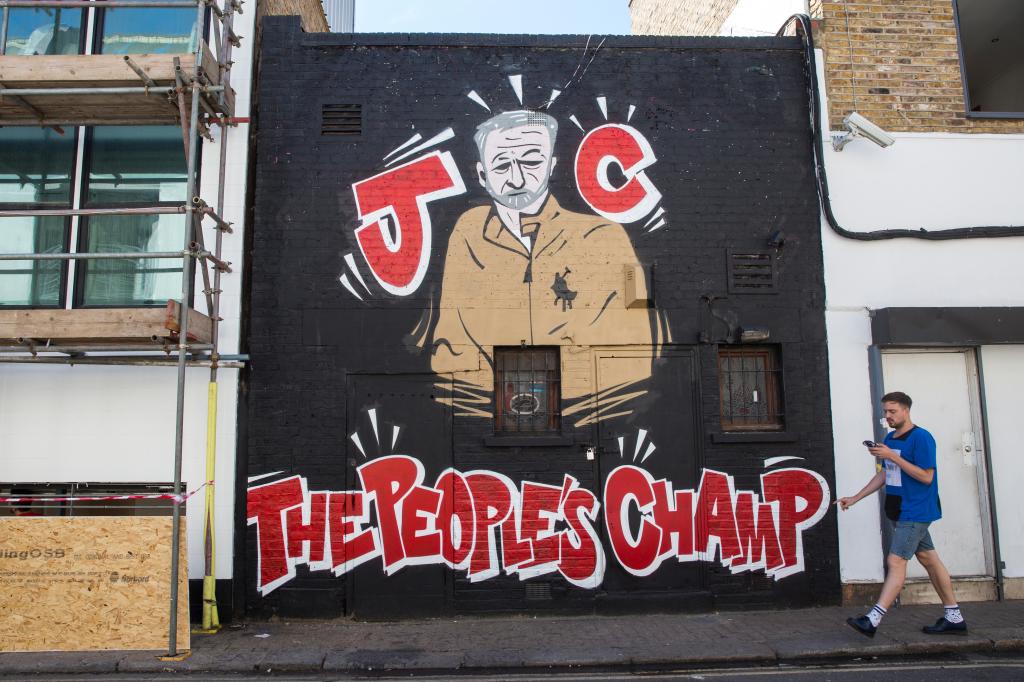

Corbyn’s message may resonate with young people, but his image has changed since the 2017 election. In his early days as leader of the opposition, optimism was high and Momentum rode the new wave of ‘Corbynmania’. “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn” was chanted everywhere, from streets to festivals, and Corbyn made an appearance at Glastonbury. But it’s hard for any politician to remain untarnished. Antisemitism accusations have meant that many Jewish voters feel unable to support a party under Corbyn, and some artists involved in the 2017 Grime4Corbyn campaign have now complained of feeling “used” by the Labour leader.

Parker says that the change Momentum wants to see has to go beyond a single figure. “People often think it’s all about Jeremy, because Jeremy was the figurehead for this movement,” she explains. “The changes that we need to bring are so significant that they’re gonna last way beyond Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell.”

Ahead of the 2019 election, Momentum, alongside its strong digital campaign, will focus on canvassing. As of August 2019, Labour has 485,000 members, and many non-members who will be able to door-knock, phone bank and leaflet potential marginal areas. The Conservatives, on the other hand, only have 180,000 members, many of whom will be older and presumably less likely to traipse out in the November cold. In the last election, Momentum targeted marginals, rather than trying to defend Labour safe seats, which proved crucial to winning. This year, it’s doing the same, outlined in its “Plan to Win” document. While the Conservatives may have more money than Labour, when it comes to people power, Labour are rich.

I speak to Simon Youel, a Labour supporter who started working for Momentum shortly after the 2019 election was announced. Youel negotiated a temporary break from his job to come and work for the organisation, supporting its press department in the run-up to the election. “I was working for a non-profit research and campaign group,” he tells me. “As soon as [the election] was called, I was ready to drop everything and give it my all.”

Momentum also has a new strategy called ‘Labour Legends,’ that asks people to take time off from work to volunteer and canvass. So far, over 1,000 people have committed their time. The organisation has also introduced persuasive conversation training, which departs from traditional data collection-led canvassing and teaches volunteers to build conversations around topics they care about, using personal anecdotes that illuminate Labour’s policies.

“When I first went canvassing the Labour party was literally, ‘[Knock knock]. What’s your name? How do you vote? Thanks very much, off I trot,’” explains Parker. “No one ever persuaded anybody of anything like that.”

The day I visit Momentum HQ, the organisation is preparing to canvass in Kensington that evening, the affluent London constituency that swung Labour in the last election by 20 votes. With the Liberal Democrats optimistically considering themselves a contender despite getting only 4,724 votes in 2017, and the Tories still a real threat, it’s essential that the party holds the seat. Coincidentally, it’s also the area I grew up in.

I head down with the Momentum organisers and join around 200 others at a rally with local MP Emma Dent-Coad and journalist Owen Jones. We stand in a park near Ladbroke Grove and divide into groups, ready to canvass. I end up with Dent-Coad and other volunteers, some experienced in canvassing, others new. The ground is wet with leaves and it’s pitch black. I briefly speak to Dent-Coad, introducing myself as “one of the 20” who swung the vote in the last election. I’m not the first to say that to her, apparently.

The first door we knock on is opened by a pregnant woman with kids, who tells us she’s living in her mum’s house. She says she’s definitely voting Tory, so I ready myself for a difficult chat. It later transpires that she actually means she’s definitely not voting Tory, and we discuss issues she’s concerned about, like the NHS. It’s a good start. We knock on two more doors, an elderly man and a married couple. Both are definite Labour. This isn’t too surprising, considering that the subsection of the constituency we’re in has historically elected Labour councillors, but it’s a good sign nonetheless.

I ask Youel how he’s found canvassing so far. “After being stuck in the Momentum office for the past couple of weeks, it’s great to finally get out on the doorstep,” he tells me. “It’s a completely different story to the one I’d been seeing in the news – despite being a heavily contested marginal, I didn’t speak to anyone who was voting for anyone other than Labour.”

This changes when the group moves onto a more affluent road. Quite a few people don’t open their door, or say that they don’t want to chat. On the next road, a few doors down from a Portuguese cafe that David Cameron was heckled at, we meet a woman named Joyce in her 90s. She apologises for not inviting us in, and talks to us about living through two World Wars. She feels lucky to live in a council-owned flat in such a lovely area. She’s not sure who she’s voting for, but really wants to stay in Europe and thinks Dent-Coad has done a great job. It’s a good conversation, but I get the impression that she was a bit lonely and might have just wanted an opportunity to chat.

For the 14.3 million people living in poverty in the UK – 33.3 percent of those children – something’s got to give. Whether its the dangerous underfunding of the NHS, the rise in homelessness, or the 65 percent increase in food bank use in the last five years, Momentum is relying on people noticing and reaching breaking point to demand real change.

I ask what Parker thinks is going to happen on the morning of the 13th of December. “Someone’s got to win,” she says. “And it better be us for the sake of the country, and the climate, because this lot are not up to it.”

“We can’t afford for this to go on,” she continues. “We have unsustainable levels of inequality. I was working in Westminster recently, and I went to one Hyde Park corner, where there was a flat that was sold for £116 million, and literally a three-minute walk away, there’s a doorway with sleeping bags in it.”

“Just under no stretch of anybody’s imagination can that be acceptable in such a wealthy country. We have to win.”

More

From VICE

-

Courtesy of the Michigan Department of State -

All photos by Yushy Pachnanda -

-