A significant amount of responsibility comes with being the first and only museum in the world dedicated to LGBTQ art. Just ask New York’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.

With the public conception of “queerness” constantly evolving, the museum has to keep up, reflecting these shifting boundaries in their expansive permanent collection. Founded over 50 years ago by partners Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman, the collection spans centuries, today totaling over 30,000 objects. And it’s still growing. Today, after an expansion into the adjacent storefront in their SoHo location, the museum reopens with a new exhibition called Expanded Visions: 50 Years of Collecting.

Videos by VICE

The show presents a sweeping history of queer art through a combination of famous and lesser-known artists. Rather than strictly chronological, Expanded Visions is organized thematically, revealing one of the collection’s biggest strengths: the opportunity to trace trends throughout centuries of LGBTQ creativity. Those thematic sections include self-portraiture, the relationship between the police and LGBTQ people of color, responses to the AIDS pandemic, and surrealism and the construction of queer-friendly alternate realms. More than the art itself, the show acts as a reminder of the history of the contemporary LGBTQ rights movement—its highs and lows, and the surprising revelations that can be gained from taking in decades of queerness all at once.

VICE spoke to Gonzalo Casals, the museum’s new director, about the history of Leslie-Lohman’s permanent collection, its future and the importance of queer art in society.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

Trans-Sissi by Oree Holban, 2015

VICE: Leslie-Lohman’s permanent collection has a compelling history that, in many ways, intersects with the modern LGBTQ rights movement. How did the collection start?

Gonzalo Casals: The history of the collection is very tied to the history of the museum—Fritz [Lohman] and Charles [Leslie]’s interests, as well as the recent history of the LGBTQ community. Soon after Stonewall, Charles and Fritz started showing works by LGBT artists in their loft in SoHo, but it went beyond just showing work—it was about supporting artists and building community in that moment in history. There weren’t a lot of places where you could just get together and be yourself. I think they understood in a very intuitive way that art could be a tool to bring people together. Then they began to collect work.

Without getting too personal, Charles told me that when they met, one of the things they realized they had in common was that they slowly but surely collected work. It was one of the things that connected them as a couple. It starts from a very personal, meaningful understanding of the power of art.

How did the collection take on increased significance during the HIV/AIDS pandemic?

As our former director Hunter O’Hanian put it, there were different reactions to the AIDS pandemic—you had GMHC [the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, an HIV/AIDS activism organization,] who saw the need for social and medical services, ACT-UP, [another HIV/AIDS activist organization,] which embodied the political response, and then you have Leslie-Lohman, who saw a whole generation of artists dying. Their art and visual culture was very explicitly going to disappear with them. Families of artists who died would clean their apartment and throw their work on the street. Part of our collection is work that had been discarded by others.

Soon after, in 1987, Charles and Fritz began to formalize the work they had been doing to turn their collection into a foundation and museum. It took them four or five years to get the recognition from the IRS as a foundation, because the word gay was in the title. As they become a more public space, they were harassed by the police and complaints by neighbors, but they continued to press forward and continue to create that space for LGBT artists.

Untitled, by Jason Keeling, 2007

The new exhibition, Expanded Visions, allows viewers to both see a wide swath of the current state of the collection but also reflect on how it might grow. How do you see the collection shifting in the future?

Today, we’re looking at how we can expand on Charles and Fritz’s vision. It’s important and dear to me and timely for us, as a museum, to explore the idea of intersectionality–not only looking at how sexuality and gender affects the creation of images, but also ethnicity, race and class. It’s an important conversation that the museum can help contribute towards.

In many ways, this is a personal goal for me. I just came to the United States from Argentina 16 years ago. I became a minority—I was a queer immigrant. For some reason, even though I was out, I connected more with my Latino identity. But there were moments where my queerness would come out. Only recently did I start thinking about intersectionality and what it means to be a queer Latino immigrant. And then this job opportunity came up.

Beyond intergenerational dialogue, censorship looms large in the exhibition, revealing the consistent policing of same-sex desire and queer bodies.

To me, that’s really interesting. In particular, there’s a whole tradition of the male nude in the Western art canon from the Greeks onward. And then, in the 1940s and 50s in the United States, male nudes became political, a reason for an artist to be sent to jail. It speaks a lot to the recent history of our country and it also helps start conversations about what’s happening now.

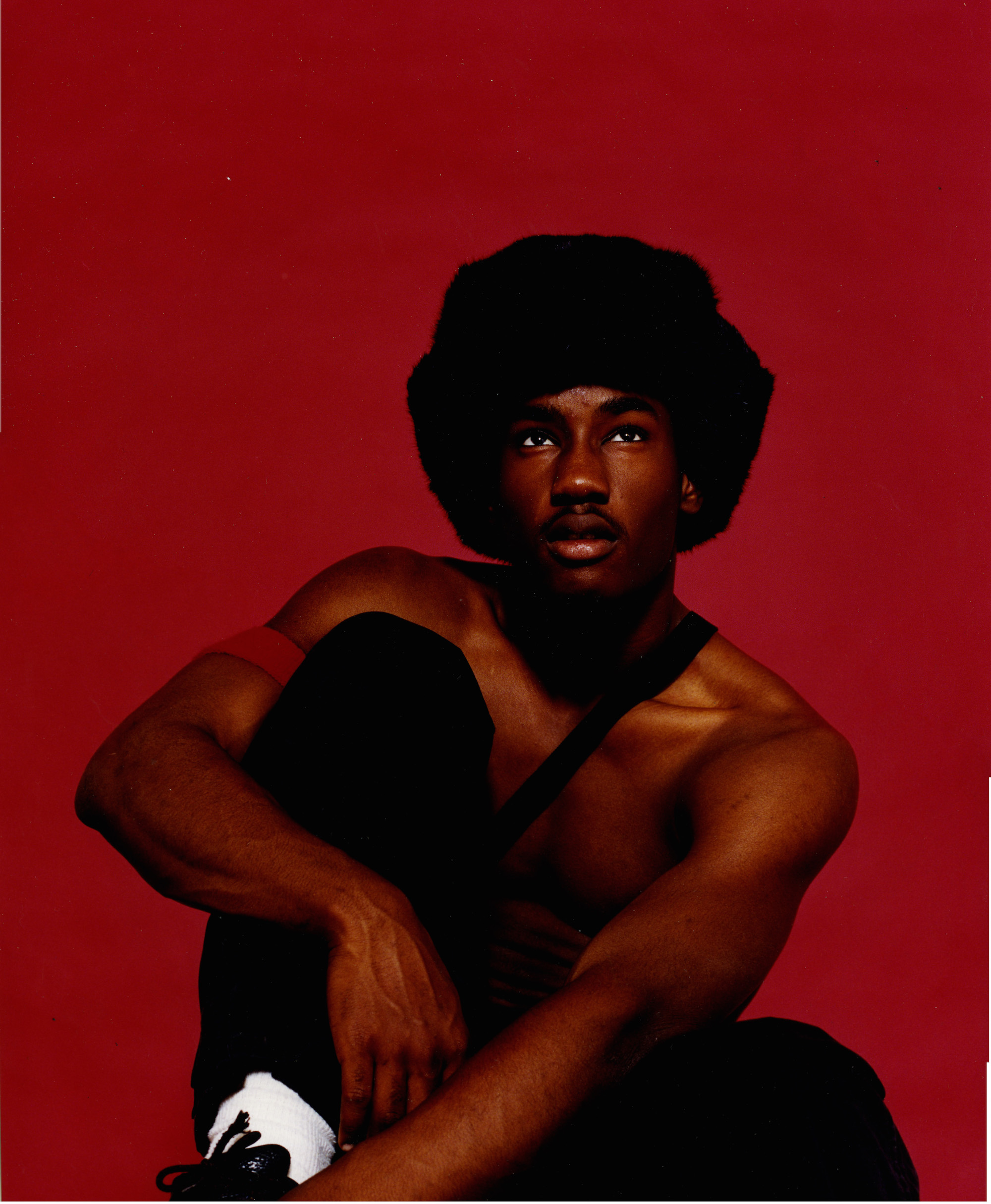

Afro Muse, by Mickalene Thomas, 2006/2014

I’m glad you mention opening conversation– Expanded Visions makes the case for the significance of queer art-making both socially and politically. What do you think is the place of queer art in society and what role do you see the museum taking?

The museum and its collection is a platform. It creates a physical and intellectual space for LGBTQ people to see themselves mirrored in society. There’s an empowerment that comes with that. They can come to a place and meet likeminded people to see they’re not the only one.

If a visitor isn’t an LGBTQ person, these works and the institution could be a window into the other. If they have a relative they don’t quite understand, a friend or even, if they don’t know anyone in the community but are curious, there’s nothing better than art to help make sense of things. Seeing a show like Expanded Visions, with its diversities and history, offers the possibility to open up a conversation. It’s about dialogue.

Follow Emily Colucci on Twitter.