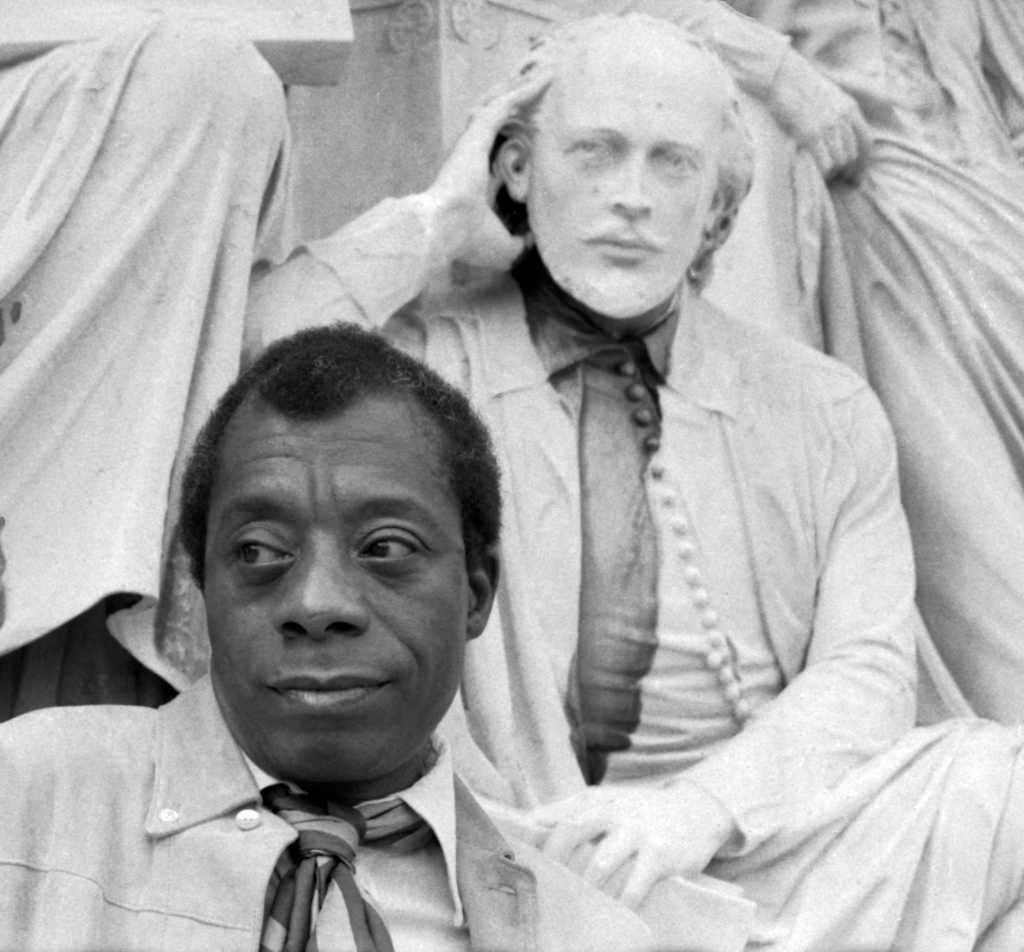

What does it mean “to discover the country which is your birthplace, to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any space for you?” That’s what I Am Not Your Negro, a new documentary by Raoul Peck about the groundbreaking author and social critic James Baldwin, seeks to answer. In theaters today, the documentary is comprised almost entirely of the author’s own words, voiced by Samuel L. Jackson.

I Am Not Your Negro is based on notes for Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript Remember This House, in which the author reflects on the legacies of three historic black men, all assassinated between 1963 and 1968—Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Medgar Evers. The documentary weaves clips from Baldwin’s interviews and speeches with notable moments from the civil rights movement to ensure their legacies don’t die in the same unceremonious way that they did.

Videos by VICE

Of course, since Remember This House is not Baldwin’s autobiography, it couldn’t be expected that I Am Not Your Negro would touch heavily on the author’s experiences as an openly gay black man, but the film only references Baldwin’s queerness once, by way of its mention in a 1966 FBI memo that’s shown on the screen, despite it being as integral to his politics and social critique as his blackness. This isn’t to say that I Am Not Your Negro is somehow lacking. Baldwin’s personal history isn’t the point of this movie; his is simply the voice chosen to give life to the compelling stories of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. But as political activism today frequently fails to be adequately intersectional, it’s important to remember that not only was James Baldwin unapologetically black, but he was also unapologetically queer.

For every The Fire Next Time, Baldwin’s 1963 book of “letters” about the racial injustices he experienced growing up in Harlem, he also wrote a Go Tell It on the Mountain, his 1953 novel about a young black boy discovering himself, featuring a number of allusions to his developing homosexuality. And for every Notes of a Native Son, his 1955 collection of essays about black life during the early civil rights era, he also had a Giovanni’s Room, his most directly homoerotic work. When his American publisher refused to release it, fearing its gay subplots would alienate his core audience, he published it in England instead. For Baldwin, it was important to be completely honest in his writings, no matter what that may have revealed about his personal identity.

That honesty becomes clear in I Am Not Your Negro, as you begin to see how Baldwin refused to sacrifice any of his identities for another. In the film, he discusses how he avoided joining organizations if they held beliefs he didn’t support; that meant refusing to join the NAACP because of their tendency to promote and condone classist elitism, Christian churches because of their failure to love everyone equally, and the Black Panthers—because, in his words, “I did not believe that all white people were devils, and I didn’t want young black people to believe that [either].”

Baldwin didn’t believe that all white people were innately evil, and he held hope that the state of race relations could improve in America, but that didn’t stop him from being openly critical against white America. The elegance and poise with which Baldwin could point the finger back at his oppressors is unmatched; he may be the only man that could simply shrug and chuckle at Dick Cavett’s tone-deaf question of “Why aren’t the negroes optimistic [about their futures]?” before calmly replying, “Well, I don’t think there’s much hope for [us, black people], to tell you the truth.” And he discussed queer sexuality, specifically for those who were black in America, just as gracefully.

Baldwin’s edition of The Last Interview includes a conversation between the author and journalist Richard Goldstein about being gay in America. Obviously, it also touched on blackness—primarily because Baldwin believed that race and sexuality “have always been entwined.” But Baldwin’s summation of what separates black homosexuals from their white counterparts is still perhaps one of his most insightful lessons.

After Goldstein, who is gay, mentioned feeling distinct from his straight white peers, Baldwin told him that his feelings of “otherness” were the result of feeling like he had been “placed outside a certain safety to which you think you were born.” Those of us who are both black and gay, however, experience life quite differently. “The sexual question comes after the question of color,” Baldwin told Goldstein. “Long before the question of sexuality comes into it,” a black gay person is already “menaced and marked because he’s black.” While being gay is just one more marginalized identity that black people are forced to contend with, Baldwin explains that for white people, being gay is simply an unexpected anomaly, whereupon they realize that they are no longer at the top of the social food chain. Baldwin maintained that Caucasian feelings of otherness based on sexuality lay in “direct proportion to [their] sense of feeling cheated of the advantages which accrue to white people in a white society.” It’s not a struggle for them, so much as a “bewilderment and complaint.”

According to Baldwin, the origins of racism lay more in white people’s refusal to give up power than in any innate desire to truly despise another human being. “They thought vengeance was theirs to take,” he said, describing how the colonialist mind works. To him, the dismantling and ultimate destruction of racism could come after white people truly took the time to understand the value of human dignity. But he also acknowledged that such epiphanies don’t occur out of the blue—that’s why he believed in the possibilities of coalitions. Baldwin admitted that he believed the (white) gay rights movement and the civil rights movement could align themselves, but only because both groups had experienced oppression from others who feared their prosperity. Blacks had dealt with white fears, while queers had dealt with the fears of straight men.

Unfortunately, Baldwin’s hopes of an integrated resistance to white supremacy, heteronormativity, cisnormativity, and other dominant American social regimes seem harder to achieve than ever. But his greater lesson is that to be hopeful for the future is not to be ignorant or blind. Baldwin may have put too much faith in the white people that he hoped would grow to see him as human, but he also made sure to hold up a mirror in his work, so they could see just how much they were breaking him (and the black community) down. That’s what I Am Not Your Negro does most effectively: It shows its audience how difficult white society makes it for black people to thrive. As someone who was used to being met with resistance both for being black and for being gay, it’s no surprise that Baldwin’s thoughts on what it means to be disenfranchised in this country were so forthright and profound.

Something about Baldwin’s hope for a better tomorrow is uplifting as our nation enters a period of political turmoil. It inspires us to keep pushing through and fighting for the recognition of our humanity—exactly as we are, whether that be gay, queer, or both. As he had it in The Last Interview: “I was not born to be what someone said I was. I was not born to be defined by someone else, but by myself and myself only.”

Follow Michael Cuby on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Instagram / Zelig Williams -

Jeremy Strong and Sebastian Stan, playing Ray Cohn and Donald Trump in new movie 'The Apprentice' -

Allmodern -

Avion Pearce