For the last two weeks the Sofia House Solidarity Centre has been welcoming homeless people from across London to a legally-squatted vacant four-storey commercial property just north of Oxford Circus – one of the ten per cent of Westminster properties owned by offshore tax vehicles.

The centre was the latest project by homelessness activists Streets Kitchen. They opened their doors on 1st March, offering not only food, clothes, medical care and housing advice, but an inclusive community with no wrong answers and few red lines.

Videos by VICE

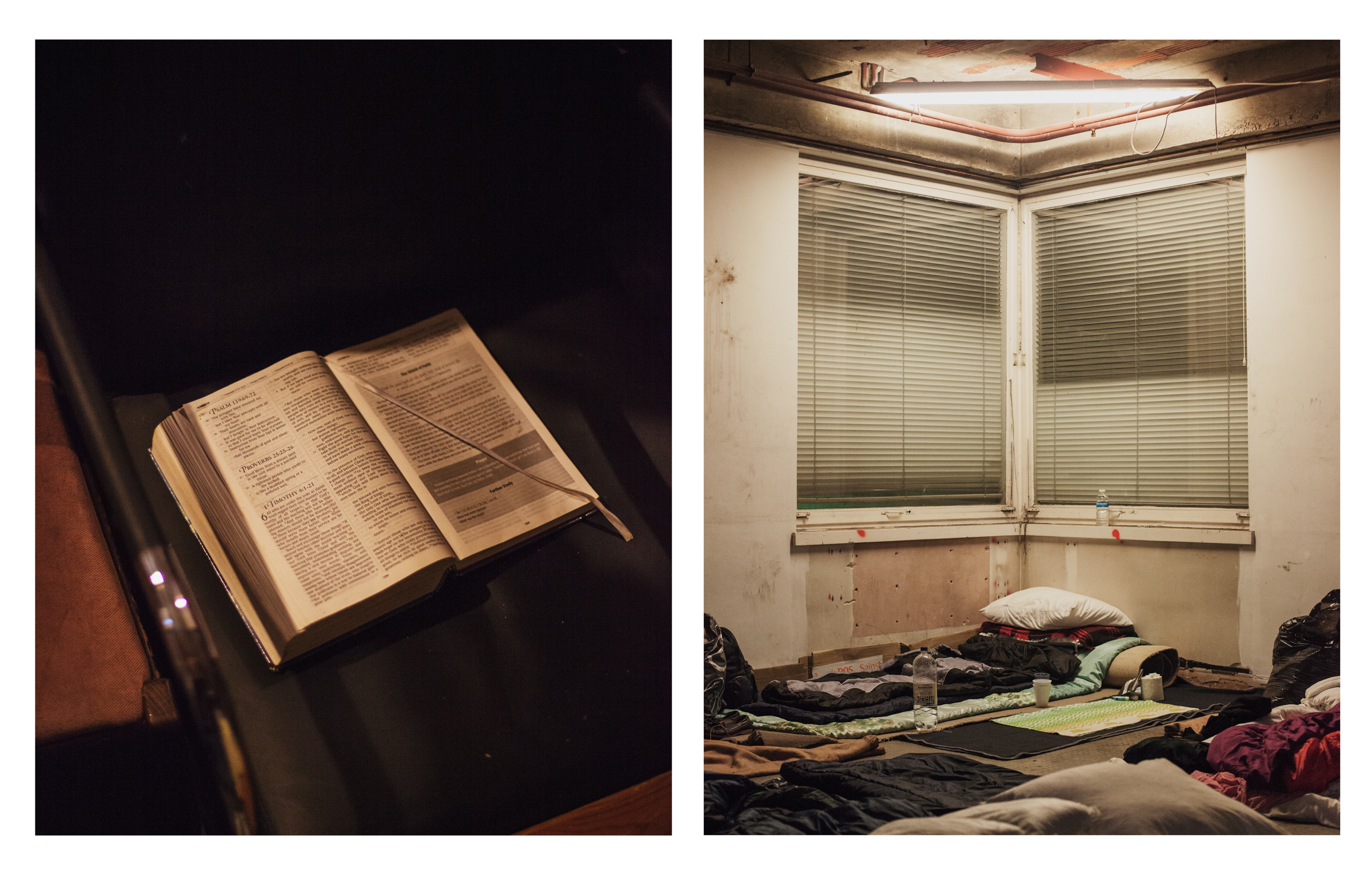

I visited the centre two days after it opened in early March. Behind a narrow, frosted-glass door, tarpaulin dividers between concrete columns broke up an otherwise large, if dingy, space. The tallest volunteers were on step ladders, fixing strings of lights to overhead cable trays. Piles of donated clothes and bedding leaned against the floor-to-ceiling windows facing onto Great Portland Street.

“This is when you see people power at its finest,” explained Sarah, a volunteer. In no time at all, a large kitchen counter was up and a microwave began reheating one of at least fifty takeaway containers of chilli and rice.

“These are perfect community spaces that we can utilise, and turn into something beautiful,” she said, as a plumber wrestled with the toilet while Franco Manca pizza boxes, which arrived full the day before, soaked up the overflow. Not perfect or beautiful in every sense, but I got what Sarah meant.

A week later, I was back at the centre to attend a house meeting. The toilet was in surprisingly good shape by this point. The pile of clothes was now a free shop, with shelves and opening hours, and most of the bedding was strewn throughout the building. But there was a tense Friday night atmosphere. With guests spread out over three floors, maintaining the centre’s drug and alcohol-free policy was getting harder. “I’m sick of being called fucking bitch,” one volunteer told me.

The meeting was messy. The conversation pinballed, and a “hands up and wait your turn” rule lasted about ten minutes. The Sofia Centre opened its doors in a moment of acute crisis, at the peak of the Beast from the East weather front that brought sub-zero temperatures. London eventually thawed, but guests continued to arrive.

The discussion seemed to circle around two questions: How long can Streets Kitchen’s volunteers continue to offer “unconditional care” to an ever-growing group of guests, many with addiction and physical and mental health issues? And: How far can and should they move away from the council model of “providers” and “service users”, encouraging guests to share the responsibility of maintaining a sustainable and inclusive environment?

“We’re doing our best,” said one volunteer, “but every night more and more people are coming, and we’re having to open more and more beds. We need people who are going to stand up, respect this place and help out.”

“There’s no voices of the residents here,” another responded. “We’re imposing our will on the building.”

The phrase “self-aggrandizing circle jerk” was used.

“Let’s just treat each other how we want to be treated,” someone suggested. I hadn’t expected a group of anarchists to talk for an hour and come up with the Bible.

One of the clearest voices in Friday’s meeting was Behar Loshi, a recovering addict and a volunteer mentor in Camden. Softly-spoken and thoughtful these days but by his own admission a rebellious and difficult service user during his addiction, Loshi has been on both sides of a divide that the centre is blurring. I wanted to know whether lessons learned here could ever feed back into professional outreach services.

“You don’t see this in professional organisations,” said Loshi of the Sofia Centre’s approach to its guests. “I’m in those places, and they struggle with these people.”

Escaping cycles of homelessness and addiction, he explained, is only possible from a place of security and ownership. Responsibility is essential to building that sense of security. “It’s quite healthy to be made to feel responsible. These people haven’t been trusted with anything in a long time. We’re talking about smart responsibility: specific, measurable, realistic. Bite-sized.”

And his own experiences tell him this works. “My recovery got started accidentally,” said Loshi. “I found a key worker that cared. I was just looking for that glimpse. I recognise it in everyone now: you give them care, instead of giving them targets.”

Loshi is far from the only volunteer at the centre with experience of addiction and rough sleeping, and is convincing in his belief that roles like his – where support is provided by people who’ve lived the experience of those they’re supporting – are the future of our approach to homelessness. But it’s hard to shake the feeling that Streets Kitchen’s ethos of ‘solidarity, not charity” will always be irreconcilable with state services, and is often predicated on their shortcomings.

“We’re not a political movement,” Streets Kitchen’s founder Jon Glackin often says, “but what we do is by its nature political.”

Later on, Glackin nudges me as he passes and points towards the kitchen. “Look at that!” Behind the counter, three guests are making lunch, tidying as they go. “It’s happening,” he said mischievously. “It’s fucking happening!”

Here and there, it was happening. Tony, 51, spends his time as the centre’s doorman. He calls himself “Oz 2” after Ozzy Osbourne, and has spent over half his life sleeping rough. More of a “watcher” than a people person, sitting away from the crowd gives him space for reflection.

“I thought it was hell, here, at first,” explained Tony. “I don’t get on well with so many people, but I’ve got a lot more confidence since I came here.” He leafed through the pages of the centre’s guestbook, as he spoke to me. “It’s a bit of space to be what I really am. I might not look it on the outside, but I’m a happy person.”

I asked Tony if he still think this is hell, five days on? “No, no,” he said, half to himself. “I like it here. I’m loving it. I’ve met a lot of people here I could call friends. I hope I can call them friends.”

Some of the guests, like Sid, slept for days when they arrived. “It’s comfortable, man,” Sid said, “wonderful.” Many guests left behind doorways and cardboard for a double mattress, clean bedding and a community. But when he wakes up, Sid, like many others, is waiting for the axe to fall. “I get the fear, a bit,” he told me, fidgeting. “I can’t stop thinking about it. What’s going to happen when we get asked to leave here, are we back on the streets again?”

Volunteers counted 160 guests on Tuesday night, the 24 hours before the court decision was due. When it finally came, it was expected: the building’s owners were granted the right to evict everyone in there.

“These people are going right back out there,” said Glackin after the verdict. “Death haunts them out there. This is when we need councils to get behind us. Give us buildings. Give us the resources to do this properly. We shouldn’t have to take buildings, we should be given them.”