Detroit, the city that gave birth to cars and techno, is fueled by a full tank of stories. Etched into dance music’s collective memory is the grand narrative of techno’s beginnings with the Belleville Three, stitched together with thousands of endless nights half-remembered by those who lived, loved, fucked, and fought to the raw sounds taking shape at parties across town. Then, there are the lost tales of musicians who never made it, and the mythologized legends of the ones who did. But there is one story that evades our every attempt to pin it down—that of Moodymann (born Kenny Dixon Jr.), the second-wave Detroit DJ and producer who infamously doesn’t give a fuck about playing the music industry game.

Dixon’s debut album in 1997, on Carl Craig’s label Planet E Communications, was called Silentintroduction. And he meant it: Moodymann declined to speak with the press for ten years, until he finally gave his first interview to Gilles Peterson on BBC Radio 1, in 2007. During a rare RBMA lecture in 2010, he explained his reclusiveness, saying: “My identity was not important… Fuck the DJ. The talent is on the turntables and that is the truth.”

Videos by VICE

In town for Movement festival in late May, I find myself shooting the shit outside the Submerge record store with Carl Craig (who I am shadowing for a forthcoming story) and Underground Resistance co-founder “Mad” Mike Banks. Mike is telling me where to find underground street races in the city, but our eyes keep drifting to a three-floor brick house across the street. Its windows are thrown open, violently purple curtains billowing in the wind, as Prince’s “Take Me With You” plays at full blast, his voice sliding down the baking sidewalk like marmalade.

7 Electronic Producers Reflect on What Prince Meant to the Dancefloor

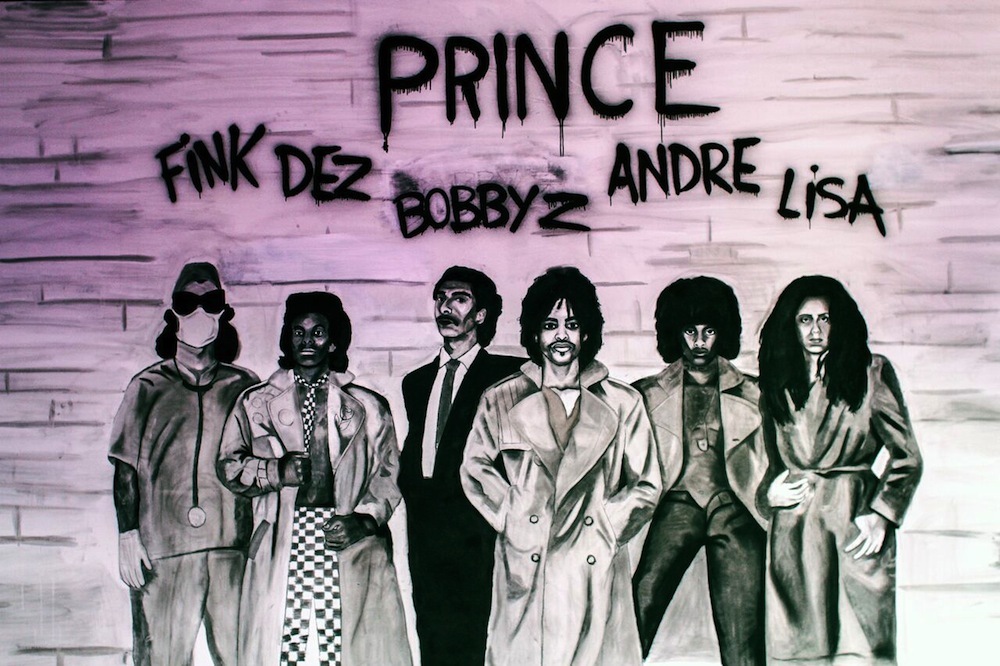

“That’s one of the places where Kenny lives,” reveals Craig. “Let’s go say hi.” So we cross the street and I climb up wood planks fashioned into a narrow flight of creaky stairs, a sense of serendipity swirling around my ankles. Once my eyes adjust to the cool, dark interior, a sense of being suddenly hit by something rare and sublime: the house has been transformed into a personal Prince shrine, Dixon’s longtime collection of records, T-shirts, shoes, and other rare memorabilia proudly displayed on the walls.

The floor’s made of polished wood, like you could tug on a pair of skates and cruise across the living room, get accidentally tangled in the plum-colored sheets, and clatter into low-slung glass table, sending a silver platter of watermelon chunks and pistachio seeds flying into the air like a pop of confetti.

At first, we are told that Dixon is preoccupied upstairs and won’t be able to greet us. But a few minutes later, there he is, slinking down the stairs, Afro bristling in the wind, sinewy sun-bronzed arms sticking out of a Prince and the Revolution wifebeater—so charismatic that every move is a pose. He gives Craig a hug, and when I introduce myself and ask if our photographer can take a few pictures for this story, his mustache twists into a kind smile as he says, “OK, as long as I’m not in it—and thank you for asking.”

He insists on giving us T-shirts and tickets to Soul Skate—an all-ages roller skate party he’s been throwing at various rinks throughout the city since 2007—and tells me a little about the various dance styles represented on the rink.

Why Roller Skating Matters, According to People at Detroit’s Soul Skate Party

“Our skate crew that comes down here, I believe that they are totally unaware of [Movement]. I’m actually the one who introduced them to the festival,” he says. “They come from LA, Chicago, Ohio, you name it. On the floor they represent where they’re from. If I’m talking to a gentleman right now, I might not know where he’s from. As soon as he puts on skates, and goes three feet, I know this muthafucka’s from Chicago. Or he’s from LA. East LA! That dog’s from the west side. They all have different styles.”

Two women suddenly appear through the door—friends and relatives of Dixon’s—and we decide to move on. But before walking out the door, I quickly sidle up to him for one last question, hoping to understand the root of Dixon’s Prince worship: “What was Prince’s biggest impact on you?”

Why Prince Was an LGBTQ Hero—And a Nightmare

Without missing a beat, Dixon replies with a cheeky glint in his eye: “Girls. Women. I didn’t have to have no game, I just had to put a Prince record on. It was easy. I didn’t have to say nothing. They’ll come to the car where I’m playing it loud, and they’ll be like, ‘Can you turn that up?’ And I’ll be like, ‘No, you turn it up.’”

Laughing as I walk out the door, I turn around to look at the house one more time. Prince’s legacy has been celebrated by millions around the world, but perhaps there’s no purer expression of love than to blast that freaky motherfucker all day and night from your home, pistachio shells jumping off the vibrating floors, purple curtains like handkerchiefs waving goodbye in the wind.

The exterior of Moodymann’s house (Photo by Luis Nieto Dickens)

A charcoal mural of Prince and the Revolution by Tashif “Sheefy McFly” on the hallway walls (Photo by Luis Nieto Dickens)

Snacks on a silver platter and a checklist of Prince-inspired T-shirts later sold at Moodymann’s Soul Skate party (Photo by Luis Nieto Dickens)

Moodymann, Carl Craig, and Craig’s publicist Kim Booth in the living room (Photo by Michelle Lhooq)

Walls lined with Prince records and other memorabilia (Photo by Luis Nieto Dickens)

(Photo by Michelle Lhooq)

(Photo by Luis Nieto Dickens)

Inside the living room (Photo by Michelle Lhooq)

Michelle Lhooq is THUMP’s Features Editor. Follow her on Twitter.