Earlier this month, in a charmingly dingy community centre in south London, 250 people gathered to talk about polyamory. The organisers think Polyday is the biggest non-monogamy event in Europe – and in its four years, this was the biggest yet. “We’re at maximum capacity, way more than expected – it’s going to be tight, hot and sweaty!” proclaimed the welcome speech.

Polyamory has just gone mainstream in BBC1’s primetime drama Wanderlust, and you couldn’t help but wonder if some of the crowd had decided to attend while choking down their Merlot and Kettle Chips. That is to say, the crowd wasn’t just the likely suspects. There were some tasselled waistcoats and flares, sure, and some fluorescent hairstyles – but there was also: all sorts.

Videos by VICE

There were retired folk in cardigans; sleek, almost-famous actors; parents and children; millenials-who-can’t-buy-homes-because-they-drink-too-many-oat-milk-flat-whites. Some were polyamorous veterans, experienced at having concurrent, committed intimate relationships. Others were taking their first steps away from the monogamous doctrine.

Ethical non-monogamy (an umbrella term encompassing varied relationship styles that fall outside monogamous coupledom) seems to be on the up. Over the past five years, “polyamory” has become ten times more popular as a UK Google search, and there’s also now a dating app dedicated to alternative relationships.

Waiting for the event to start, attendees made convivial not-so-small talk about love and sex. “It’s my first time at a poly event,” one antsy but excited man told the woman next to him, “my wife suggested polyamory, and I’m embracing it.” Beside me sat a beaming trio holding hands.

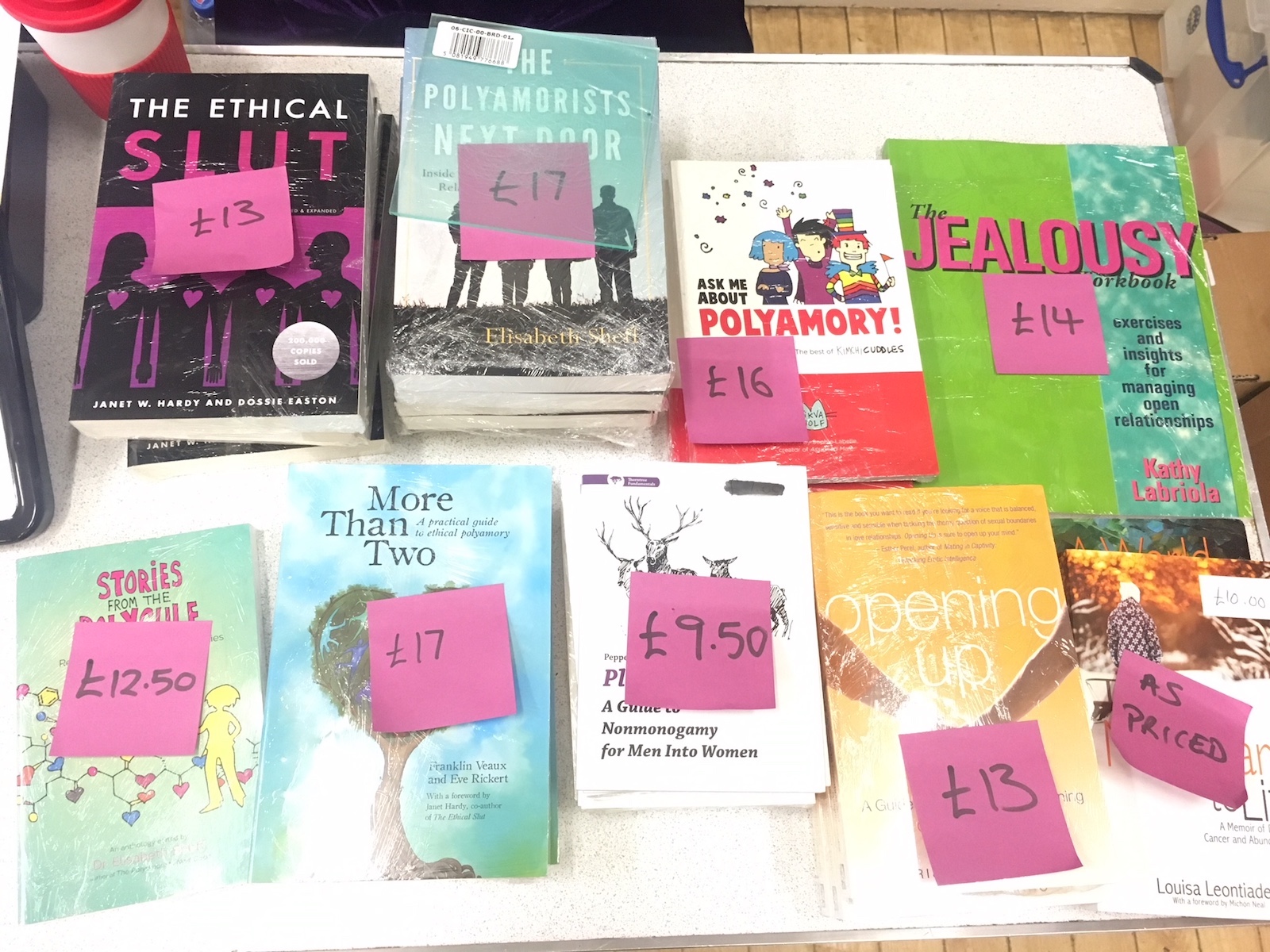

Polyday 2018 was a conference of sorts, with workshops and talks on topics from “the history of polyamory”, to “consent culture”, to “people of colour and polyamory”. In “Polyamory 201”, people shared their experiences with a vulnerability and generosity of spirit that is scarcely seen among strangers. During the “speed-friending” session, we shared names and pronouns, then discussed quite existential questions – both relating to polyamory and not.

One of the prompts during “speed-friending” was, “Is polyamory an identity, or a desirable behaviour, or something else?” For some, the desire and capacity to have intimate bonds with more than one person at once feels like a core part of their identity; for others, polyamory is more of a decision.

“For me, it’s about questioning pre-existing romantic values and norms,” said Kakinoki, an attendee doing postdoctoral research on non-monogamy. “Some people struggle their whole lives, because they are trained to be monogamous but might fit better into non-monogamy.”

In her session on the history of polyamory, sex academic Kate Lister took us on a whistle-stop tour of human sexuality. “Monogamy is weird,” she said, “it’s not our natural state and that upsets people.” But whether monogamy is natural isn’t that important – what matters, said Lister, is that “monogamy doesn’t seem to work very well”. And crucially, that it isn’t our only, or necessarily best, option – even though it’s presented as such in modern Western culture. Among the Bari people of Venezuela, Lister told us, it is common for pregnant women to have sex with various men – all of whom share parental responsibility.

“I think we live in a fear-based culture surrounding relationships,” said Matt, an attendee who is new to non-monogamy. “It’s all, ‘Oh god, don’t leave me!’ and there’s this pressure for one person to be everything.” In contrast, Matt finds polyamory “very celebratory and honouring of people”.

“It’s wonderful – when you stop looking for one person to cover everything, you can really engage with that person without the pressure,” he said. “Knowing that they don’t have to be everything, because you have a community, you have other people, enables you to be much more present.”

Unlike monogamy’s configuration, which is supposed to be straightforward but usually isn’t, polyamory is a malleable concept. It comes with its own vocabulary, said facilitator Eunice Hung, because “we live in a society that trains us to talk about love and relationships in a certain way”.

Some people identify as “solopoly”, meaning they tend not to be part of a couple or other relationship “unit”. They may have intimate relationships, but place great importance on personal autonomy. Other people have a “nesting relationship” – one that is cohabiting and closely entwined. This relationship is likely to be someone’s “primary” relationship, but not necessarily. Some people practise “kitchen table” poly, which refers to poly relationships where everyone involved in a network of relationships – even if they’re not all intimate – is friendly with each other. And that “network” of connected non-monogamous relationships is often called a “polycule”.

During one session we had “sharing circles” about opportunities, challenges and solutions in polyamory. For practical issues, Google calendars are popular. But there was also frank discussion about more delicate issues. We spoke about the inadequacy of the concept of “jealousy” – some experience it as an undesirable insecurity, others see a certain unease as both exciting and proof they care deeply about a partner. A shared frustration among Polyday-goers was “mononormative” responses to their relationship problems. Namely: “It’s because you’re poly!” (Shall we start blaming monogamy every time a couple gets bored or cheats?)

With an entire workshop dedicated to it, consent was central to Polyday. Facilitator Jenny Wilson told the packed room that the first hurdle for fully consensual relationships is often that “British people find it very difficult to talk about sex, even with people they’re having sex with.” To practise expressing our needs and desires, we used the analogy of choosing pizza toppings with other people. We all have things we “want”, things we “will” eat and things we “won’t” eat – the challenge is working out who you have enough in common with to share a pizza. “And it becomes more difficult the more people you’re dealing with!” an audience member chimes in. “You’ve got to consider the allergies of the whole group,” advised Wilson.

People at Polyday were mindful that polyamory may not be accessible to everyone. “We need to break things down and see how different people experience polyamory because of different aspects of their identities,” said Rae. In her session, hypno-psychotherapist and activist Zayna Ratty spoke about how people of colour can be reluctant to enter polyamorous communities that are predominantly white, and how we can fight against racism in polyamory by platforming people of colours’ stories, targeting gaslighting and stopping barriers to entry.

Polyday clearly attempted to foster an atmosphere of loving inclusion for all – and it wasn’t until the final session, a panel discussion on LGBTQ+ and polyamory, that the pervasiveness of polyphobia became apparent. “There is a societal driver, whereby monogamy is what people ‘need’ to do,” said organiser Marcos, “and people who steer away from that are seen to be steering away from core beliefs that are essential to the functioning of society.”

Panelist DK Green, who has a long-term relationship with two co-parenting partners, was once investigated by social services after someone at his child’s school made a complaint. The authorities came to his home and interviewed his children. “It was the scariest and most empowering period of my life,” he said. “By the end they apologised and were very respectful – they thought it was weird, but they got an education.” Another panelist, Charlotte Davies, said her holiday accommodation was once cancelled on the grounds of her being polyamorous.

There was some debate in the audience as to whether poly had a place at Pride, but the panelists’ take was clear. “If Pride is a protest, polyamory absolutely has a place there,” said Davies. The key, she added, is the discussion about who takes up space: “The more privilege you have, the more you should shut up.”

There was no dogma at Polyday that non-monogamy was a “better” way of living – just a sense that life would be better for everyone if we were free to build our intimate bonds in the way that felt best to us, not to societal conventions.

“I use ‘polyamory’ as a shortcut, but what I really identify as is a ‘relationship anarchist’,” said Marcos, “which is a relational philosophy where every single relationship has its own mechanisms that are not imposed by societal expectations, and rejects the idea that sexual and romantic relationships are more important.”

Relationship anarchy, said Marcos, might be helpful for everybody: “The idea that you need to be in a couple is really damaging. I think that absolutely everybody – whether you fall in love with someone new every day, whether you fall in love with one person for the whole of your life, or whether you never fall in love, never have sex – can explore relationship anarchy, solely on the basis of healthy, consensual relationships.”