(Top image: Angus Bean – “Quentin Crisp” (1941). All images courtesy of Tate Britain.)

2017 marks 50 years since the decriminalisation of homosexuality in this country. This is a complicated anniversary: on one hand it’s a milestone for freedom of expression; on the other, a shameful reminder of how recently liberties which we now take for granted were denied by law, and the lengths that queer rights still have to go.

Videos by VICE

These complexities form the basis for Queer British Art 1861-1967, a major new exhibition at London’s Tate Britain. The show covers art made in the century before homosexuality was officially legalised, and spotlights creators who were marginalised by society at that time on account of their sexual preferences. It includes work by artists we would now consider to be gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans, and is a valuable look at the resistance and tenacity displayed by queer people even when their very existence was criminalised.

To find out more about the exhibition and specifically why it matters right now, I spoke with meme-loving King’s College London PhD student Ellie Jones, who has been working on Queer British Art alongside its curators.

Henry Scott Tuke – “The Critics” (1927)

VICE: The exhibition is happening because it’s been 50 years since the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK. Do the pieces in the show reflect that gap in time, or do you think they still resonate today?

Ellie Jones: For much of the period covered in the show, terms like “lesbian”, “gay”, “bisexual” and “trans” weren’t actually widely recognised, and many of the artists featured don’t fall neatly into these categories as they’re understood today. Landmark events like the Wilde trial in 1895 [when the author Oscar Wilde was put on trial for homosexuality] helped bring sexual identity to the forefront of public debate, before which sexual practices or forms of gender expression were not really considered a central part of the self. The art of this period reflects this fluidity, in often surprising ways.

That being said, the issues artists faced a century ago remain as urgent today as they were then, and it’s not as if we can look back from a place of complacency. Artists in the Bloomsbury Group [an influential group of creatives active in the early 20th Century], for instance, really question how sexuality informs every corner of our existence – “Who can we live with and in what way?”, “What does it mean to be mostly attracted to men but in love with a woman?”, “How can we escape gender?” You get the gist.

The exhibition explores the fundamentals, really: what does queer art look like, or what makes an object queer? Is it always about bare butts and being camp? Of course not – although they are both important.

Paul Tanqueray – “Douglas Byng” (1934)

In that case, do you think there’s a strand of queer culture that has just always sort of been there?

Part of the reason behind showing pre-decriminalisation artwork is to show that queerness has always and will always find expression, even when it is legally dangerous to do so. The range of objects on show – from portraits of lovers to costume designs for drag performers – speak to the playful and innovative approach queer artists have taken in the face of oppression. There’s some tragic stories but also some moments of humour, triumph and liberation. This diversity and creativity are still intrinsic to queer communities today.

So how do you think queer art in the UK has changed since 1967, when the show’s time period ends?

The majority of the work in the exhibition is centred on bodies. Artists working in the lead up to decriminalisation, like Keith Vaughan, David Hockney and Francis Bacon, do start to push the boundaries of figurative representation, and you can see how abstraction informed their practice.

Since then, though, queer art has proliferated and diversified in tandem with increased accessibility to materials, digital media, and the internet. Tate’s 2017 programme includes exhibitions and displays by a range of contemporary queer artists which demonstrate these changes, including Wolfgang Tillmans and Cerith Wyn Evans.

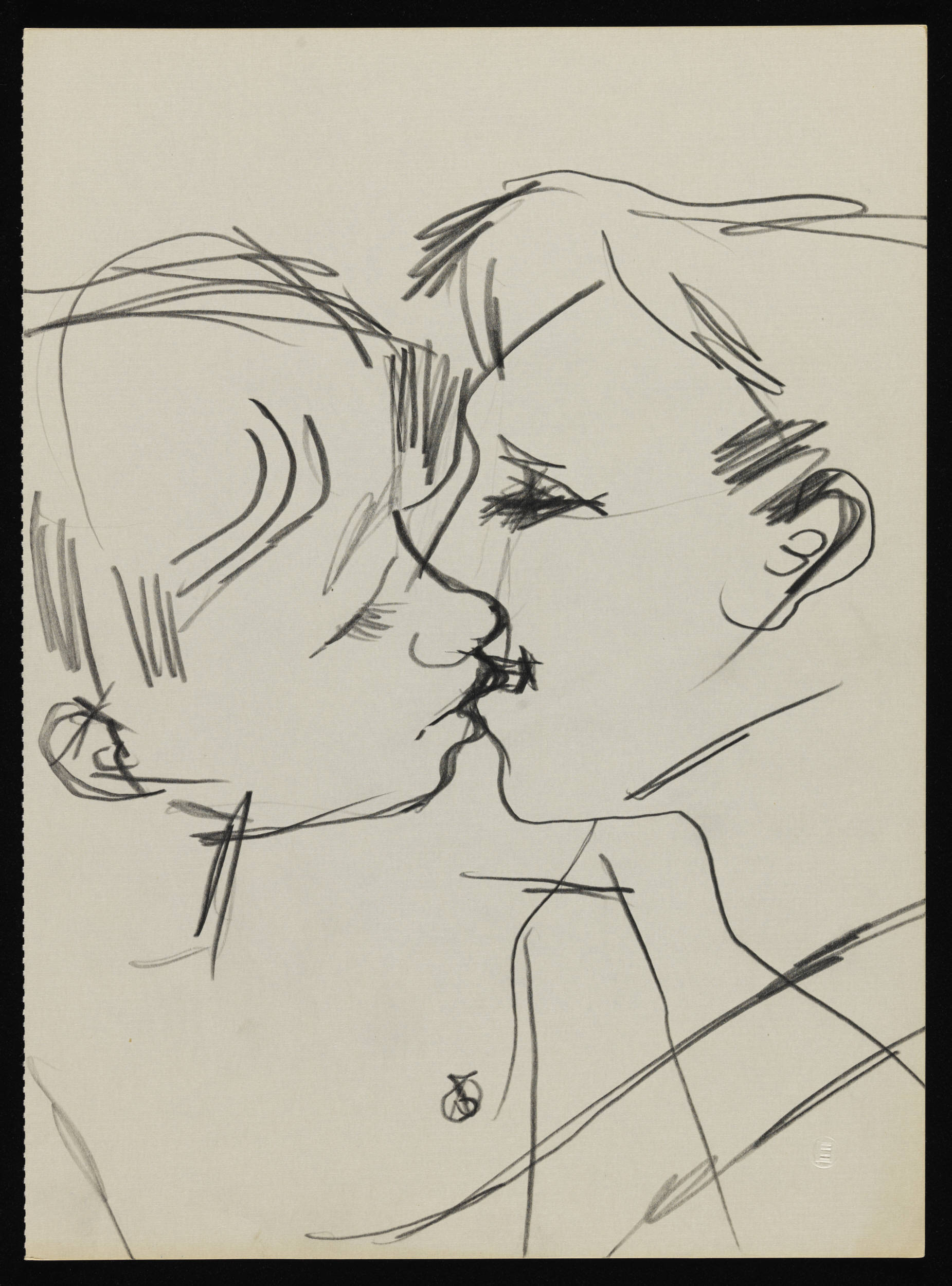

Keith Vaughan – “Drawing of two men kissing” (1958-73)

To change tack for a minute, what are the responsibilities involved in putting together an exhibition like this?

We’ve tried to include material that connects to the widest possible range of identities and experiences. Queerness is so diverse, and there are some perspectives for which, given the time frame of the exhibition, we found little material. Being the first exhibition of its kind, it’s hoped that Queer British Art is the start of a wider conversation about how queer experiences are represented and preserved. We’re keen that people know that this is not a closed canon of queer British art, and it is not definitive.

In terms of “responsibilities”, the art world can often seem a bit alienating for quote-unquote “young people”. Do you think that exhibitions like this, which tap into the identity politics which so many millennials are now acutely aware of, are an effective way of bringing younger people who haven’t studied art into the traditional gallery space?

Yes, and I think this show in particular reconsiders or probes at what can legitimately be shown in the gallery space. Critics Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer have discussed the need for “curatorial promiscuity” when it comes to exhibitions and collections concerned with sexuality.

What are the most special parts of the show for you? Is there anything you would recommend people look out for?

One of my favourite objects is a drawing by Simeon Solomon called “The Bride, Bridegroom, and Sad Love”, which I guess can be summated as a heart-breaking representation of the third-wheel. Its presentation of ostracised and impossible love is frankly gut-wrenching. I also love the costume designs by Edward Burra for ballet performances inspired by French sailors. He made the men’s bodices extra tight, and edged the sleeves with sequins and feathers, because of course. Where else in London are you going to be able to see a pink wig from a 1920s female impersonation act, racy magazines from the 1950s and the door of Oscar Wilde’s prison cell alongside Duncan Grant’s erotica, photographs by Claude Cahun and paintings by Francis Bacon? I ask you.

Solomon, Simeon – “Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene” (1864)

Do you have any cool stories from when you were sourcing pieces for the show?

One of the most surprising stories for me was the huge number of glamorous female impersonation acts on the stage from the 1900s to the 1950s – the forerunners of drag – without whom there might even be no RuPaul’s Drag Race, perish the thought. There are some stunning photographs of performers during this period. I was also struck by the cross-genre exchange between the visual and performing arts, with queer artists lending their vision to performance.

Finally, can you speak a little bit on what you think is the significance of the show? Why is it important and necessary now? Why should we even come see it?

I’ve recently been reading the artist David Wojnarowicz’s book Close to the Knives, and there’s this one section which I’ve reread loads, which concludes: “Sexuality defined in images gives me comfort in a hostile world.”

I think that quote does a lot of work. The show gives voice to lives and experiences which have been silenced, obscured or completely invisible for so long. It provides relief, it gives room for anger, it has moments of sadness as well as humour.

Queer British Art 1861-1967 is on show at Tate Britain from the 5th of April to the 1st of October, 2017.

More on British art:

How To Make British Art Better

Where Are All the British Asian Artists?

What’s It Going To Take For the British Art World To Stop Cosying Up To Big Oil?