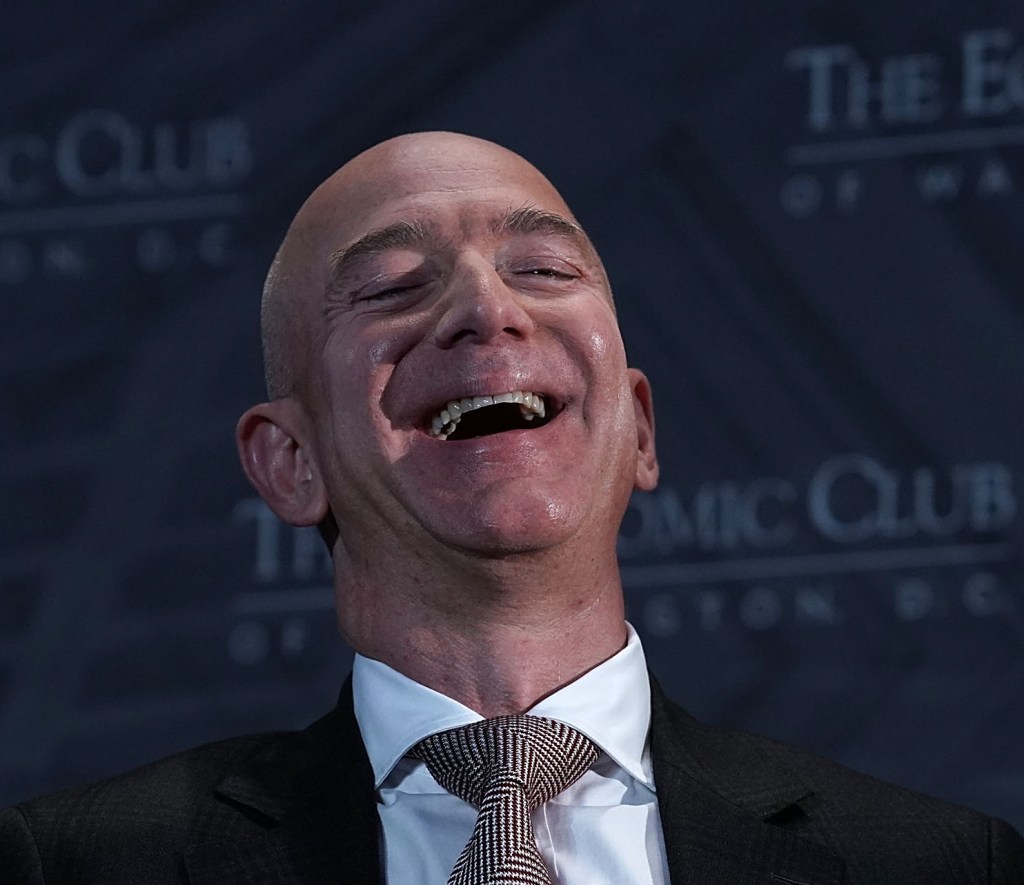

On Tuesday, the world’s richest man made a concession to the hundreds of thousands of Americans in his employ: The lowest wage of all Amazon employees in the US will be $15 an hour starting November 1, according to a statement put out by company founder and CEO Jeff Bezos. The pay floor affects part time and temp workers, as well as people who work at subsidiary Whole Foods, and it stands to impact the larger economy: Bezos has pledged to lobby the federal government for legislation that nudges other retailers to follow suit.

The decision was immediately praised not just as a #win for the progressive left, but for Bernie Sanders in particular. That’s because the liberal US Senator from Vermont created a petition in August calling out the absurdity of Bezos earning “more money in ten seconds than the median employee of Amazon makes in an entire year.” Sanders also proposed a bill last month called the Stop Bad Employers By Zeroing Out Subsidies (BEZOS) Act, which would hold companies liable if their workers needed government help to scrape by. And while it may seem naive in 2018 to think someone worth upwards of $165 billion could be motivated by anything other than craven capitalism, the statement Amazon used to trumpet the decision suggested it was in fact motivated, at least in part, by people calling Bezos out for sucking so much.

Videos by VICE

“We listened to our critics, thought hard about what we wanted to do, and decided we want to lead,” Bezos said. “We’re excited about this change and encourage our competitors and other large employers to join us.”

Of course, it’s not that simple. Historically, critics have argued, much of Amazon’s growth came from bleeding and buying out rivals. The idea was that if competitors refused to be acquired, Amazon could just sell whatever they did at a loss, not having to worry about shedding money in the meantime thanks to incredible overall revenue and market share. Eventually, the smaller company might go out of business—or at least be rendered vulnerable. That’s what happened with Zappos in 2009, and, right now, Amazon may want to pressure competitors like Target into taking on an expense—higher wages—they weren’t necessarily prepared for, and fail.

To figure out whether the Bezos announcement was a good thing, a sinister one, or both, I called up Marshall Steinbaum, a research director and fellow at the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute. He painted a dark picture of the world’s richest man wielding incredible power over the American labor market.

VICE: How much of this minimum wage increase is actually the result of political pressure from people like Bernie, and how much is it about their competitors?

Marshall Steinbaum: I think broadly speaking it is partly right to say it was caused by political pressure. There’s no way of knowing in particular if it was caused by the introduction of the [Stop BEZOS] bill by senators in Congress, but my impression is that Amazon has taken a lot of flak for bidding these HQ2 proposals against each other and for trying to get subsidies from cities that would have the headquarters. And they’ve done that on a smaller-scale for warehouse locations. I think there’s generally been a public questioning of, “Well, what are we really getting out of this, by giving corporate subsidies for this gigantic and powerful company that is both managed and largely owned by the world’s richest person, and they’re paying out poverty wages?”

And this is repeating a pattern that has been seen in American political history before in terms of campaigns pressuring individual companies to adopt wage policies that then create pressure both in politics—to level-up the playing field—and also new standards that the same activists can then take to other companies. It is definitely right to see this caused by politics, and I don’t think that’s any way in tension with its matter of predictability in terms of labor economics, frankly. If they’re doing this to harm their competitors, more power to them. That’s the kind of competition we want.

Ok, if we’re not to be cynical about this, then, to what degree should we be concerned that they seem to have the ability to influence the entire labor market, and that the benevolence of a billionaire is many people’s best hope for economic mobility?

That’s what it means to live in a high inequality society. That is to say the whims of a few rich people determine the life or death or living conditions or basic subsistence of hundreds of thousands if not millions of individuals. I would say it’s not quite correct to interpret this news as benevolence on Bezos’s part. I think it was in part a calculation on the political pressure that he and the company are under and if that political pressure yields some particular concession to demands, then it’s not right to say that he’s just deciding on a whim who gets what. But yeah, I think your basic inclination is right. Is this the best we can hope for in the economy we currently live in? Yeah, kind of. And that sucks. So why don’t we change the way the economy works?

Amazon is effectively immune from antitrust laws because it’s made products cheaper for consumers, right? How did the law get that messed up?

The basic background is that we’ve had the same antitrust laws that we’ve always had since 1890. But the enforcement of them and the core precedents that determine how they’re enforced have been weakening ever since the 1970s. And that is based on an ideological transformation of the federal judiciary, and in the particular case, in the influence of a particular school of economics that thinks antitrust law was bad, that it was economically illiterate, and that if you truly understand how the economy works, a company like Amazon presents no problem.

The reason why is that it’s good at presenting low prices, and the antitrust laws have devolved to the point that if they do that, then that’s kind of a get-out-of-jail-free card. And that’s an invitation to engage in all kinds of other anti-competitive behavior. Now it’s commerce, logistics, delivery, they manufacture a ton of goods, they’re not just a streaming service but they produce original content. Amazon web services is now a big piece of their profits—they have something ridiculous, like 36 percent market share—and now that’s powering everything else that they do. And I don’t know exactly how they use it, but I would say it’s scary that other companies are operating their cloud computing services via Amazon’s platform, because that means Amazon basically gets to see what everyone else is doing. And they certainly can use that advantage to great effect in terms of expanding their own power.

All of those things would have raised red flags in the past among antitrust enforcers, whereas now they just look at the low prices and say, “Great. This is the kind of company we want. We want them to control so many markets because they’re benefitting consumers.” And if they’re making it impossible for anyone else to earn a living and setting wage policies for the rest of the country, as they potentially are, it’s of no concern.

Is there any precedent for a company like this having such a stranglehold over the US economy?

I was at an economics conference where a colleague of mine pointed out that in the 30s, The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P), which was then the dominant retailer, controlled 2 percent market share of all retail stores direct to consumers. Congress enacted a law called the Robinson-Patman Act, which is actually still around, although it’s almost never enforced. And that made their business model illegal. So under that act, you’re not allowed to price discriminate. That meant the A&P was basically squeezing the profits out of retail supply chains, so if you were unaffiliated with the A&P, if you were trying to sell your goods, the A&P would either exclude the good from their store or pay you very little for them. They were kind of consolidating retail in the same way Walmart and now Amazon have done.

And that was our policy for a while until we decided to stop enforcing that policy in the 1970s. Anyway, this guy at the economics conference said that between Walmart and Amazon, they have 10 percent market share. And if we don’t do anything about that, we are going to see a Robinson-Patman Act. And I think that’s a good point. The politics of it are such, that I can’t really imagine people tolerating one or two companies having such broad sway over the US economy—as you were saying, today we’re talking about a wage policy that’s good to some degree, but all it says in the larger sense is that one company sets the terms for the entire labor market.

Rather than try to hold Bezos liable for the government help his employees may need to make ends meet, as Sanders is doing, is anyone trying to close that antitrust loophole?

Congress has not acted substantively in the theater of antitrust in a really long time, and there’s some policy capacity there, but mostly they have deferred to agencies, and especially courts. And my view is that it’s gotten to the point that the policy is unsalvageable without Congress stepping in. There’s definitely a rising chorus that we need to get the train back on the tracks here.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Allie Conti on Twitter.