OceanGate Expeditions, the exploration company behind the submersible now apparently lost beneath the Atlantic Ocean, spent years positioning itself as a boundary-breaking firm that existed outside the “industry paradigm” and prioritized “rapid innovation” above approval from outsiders.

While it’s not clear what, if anything, has gone wrong with the company’s submersible, it is clear that OceanGate has marketed itself as prizing innovation and disruption above rigorous, industry-standard safety testing, claiming to have crafted vessels so exotic it wasn’t even possible to test them within the currently-existing paradigm.

Videos by VICE

The company’s CEO and co-founder, Stockton Rush, had repeatedly positioned OceanGate as the deep-sea equivalent to space tourism outfits like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic—moving too fast to align with all pre-established rules and guidelines in an effort to push the industry forward faster than previously.

Rush among those aboard the missing boat, the company confirmed to Fox News on Tuesday.

Stockton Rush “christens” the Titan sub five years ago.

On its website and in the press, OceanGate has frequently boasted about the innovative designs of its vessels, including a carbon fiber and titanium hull, an “unparalleled” hull monitoring system, and an electronic control system.

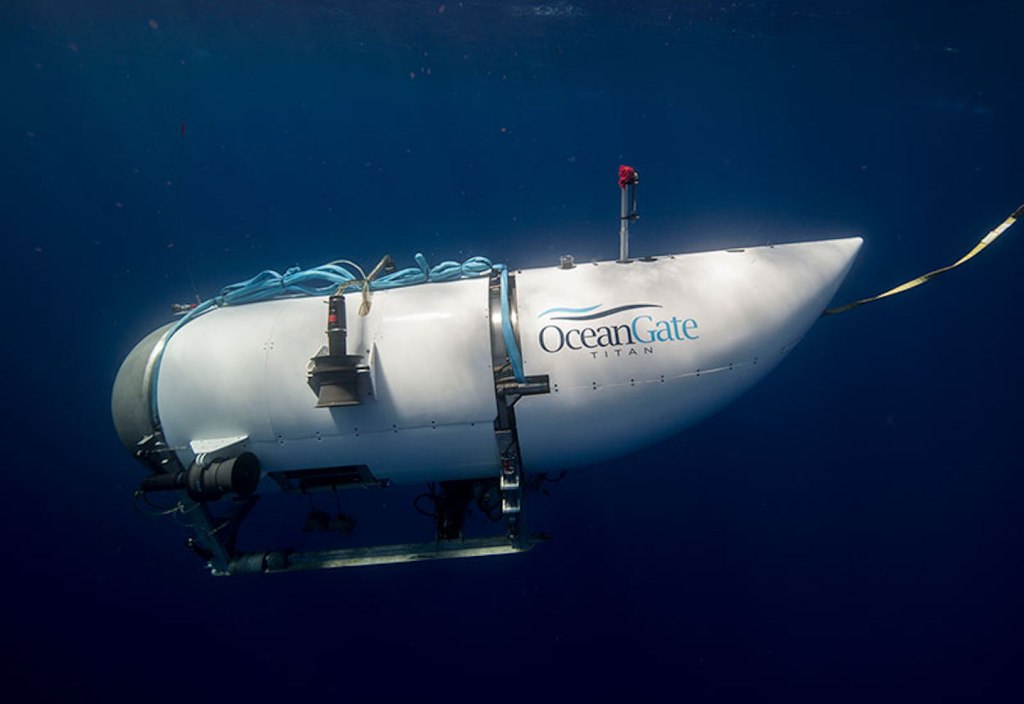

Of particular pride was the Titan, an “easy-to-operate” five-person submersible that is now lost beneath the Atlantic, where it had been on a mission to view the wreckage of the Titanic, which sank to the bottom of the ocean in 1912. Prior to the Titan, the only submersibles that had been capable of reaching the world’s oceans average depth had reportedly been owned by the U.S., French, Chinese, and Japanese governments.

Do you have information about OceanGate or the luxury travel industry? We want to hear from you. From a non-work device, contact our reporter at maxwell.strachan@vice.com or via Signal at 310-614-3752 for extra security.

Prior to this week, the company had bragged that the Titan made “innovative use of modern materials,” including “off-the-shelf components,” that helped “streamline the construction” and made it “more cost efficient to mobilize than any other deep diving submersible.” The use of “off-the-shelf technology” additionally made it easier to “replace parts in the field,” a “unique advantage over other deep diving subs,” the company said.

OceanGate had long positioned itself as a disruptor in the field of ocean technology. In a 2019 post published to its site, the company said when it was “founded the goal was to pursue the highest reasonable level of innovation.” As a result, it said, the company “by definition” operated “outside” of the “already accepted system” and the “existing industry paradigm.”

In the same post, the company also took aim at classing—which, in the company’s description, “assures ship owners, insurers, and regulators that vessels are designed, constructed and inspected to accepted standards.” While classing standards “do have value,” the company explained, they were on their own “not sufficient to ensure safety.” More to the point, the company said, classing agencies’ “multi-year approval cycle” for “ innovative designs and ideas” were a primary reason that the Titan was not classed.

“Bringing an outside entity up to speed on every innovation before it is put into real-world testing is anathema to rapid innovation,” the company said then.

In a profile published months later in Smithsonian Magazine, Rush, the company’s CEO, described concerns about deep sea exploration as “understandable but illogical” and criticized regulations governing the commercial sub industry as “obscenely safe” and the reason that the industry hadn’t “innovated or grown” since at least 1993, when the Passenger Vessel Safety Act of 1993, as Smithsonian put it, “imposed rigorous new manufacturing and inspection requirements and prohibited dives below 150 feet.”

In the article, the journalist wrote that Rush believed the law “needlessly prioritized passenger safety over commercial innovation.”

The article depicted Rush as “maverick CEO and co-founder,” “daredevil inventor,” and “real pioneer” who had a disposition toward Star Trek references and dreamed of becoming an astronaut before vision issues made the goal impossible. He soon turned toward the sea, portraying it as a more daring area of exploration.

“I had this epiphany that this was not at all what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist. I wanted to be Captain Kirk on the Enterprise. I wanted to explore,” he told Smithsonian.

After the article was published, Smithsonian added an update saying that the company had been unable to secure the proper permitting and had to postpone its trip to the Titanic. It was one of a number of setbacks that OceanGate has dealt with. In 2018, the company reportedly postponed trips to the Titanic after deep-water tests in the Bahamas, where the Titan’s electronic system reportedly “sustained lightning damage that affected more than 70 percent of its internal systems.”

“While we are disappointed by the need to reschedule the expedition, we are not willing to shortcut the testing process due to a condensed timeline,” Rush said then in a news release. “We are 100 percent committed to safety, and want to fully test the sub and validate all operational and emergency procedures before launching any expedition.”

Late last year, CBS correspondent David Pogue toured the Titan. Before he did so, Pogue signed a waiver on camera that said the vessel “experimental submersible vessel that has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body and could result in physical injury, disability, emotional trauma or death.” As part of the segment, Rush took Pogue inside the five-person submersible, which he said included parts from Camping World and was operated using a simple “game controller.” (“With a little bit of training, if you know how to play a video game, you can drive one of our subs,” a company rep said in a video posted to YouTube.)

“We only have one button, that’s it,” Rush told Pogue at the time. “It should be like an elevator, it shouldn’t take a lot of skill.”

During the segment, Pogue said he was struck by “how many pieces of this sub seemed improvised” and included “some elements of MacGyvery jerry-rigged-ness,” like using “construction pipes as ballast.” Rush pushed back, saying that the company had worked with NASA and Boeing on the vessel.

“Everything else can fail. Your thrusters can go, your lights can go, you’re still going to be safe,” he said then.

But during Pogue’s reporting trip, the sub was lost for roughly five hours while he was on a ship above water, he said this week.

“They could still send short texts to the sub, but did not know where it was,” he added. “It was quiet and very tense, and they shut off the ship’s internet to prevent us from tweeting.”

The company had reportedly first decided to take civilians down into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean to view the wreckage of the Titanic as a “marketing ploy” to gain attention for the company, according to a 2019 profile in Smithsonian Magazine.

In an emailed statement, the company told Motherboard that its “entire focus” at this moment “is on the wellbeing of the crew” and reestablishing contact with the Titan.

“We pray for the safe return of the crew and passengers, and we will provide updates as they are available,” the company said.