In our Dancing vs. The State series,THUMP explores nightlife’s complicated relationship to law enforcement, past and present.

I’ve always believed that dance clubs and parties have the potential to offer far more than a place to cut loose. Historically, for marginalized communities, they’ve provided important opportunities for people to find each other—and themselves—on the dance floor. Many queer people can even trace the roots of our lesbian and gay liberation movements to social spaces. Most widely known are the riots that took place outside of New York’s Stonewall Inn in June 1969. There, queer and trans people fed up with constant police raids of gay gathering spots fought back and never stopped moving forward. In Toronto, police raids of four gay bathhouses on February 5, 1981 sparked mass protests and galvanized a community.

Videos by VICE

And in Montreal, following years of institutional discrimination, a broad queer movement mobilized in response to the police raid of Sex Garage on July 15, 1990. Cops didn’t just shut the after-hours party down; they lined up outside to block its exit, batons in hand, and harassed hundreds of patrons attempting to leave. Attendees were blatantly beaten on the street. The Sex Garage raid ignited clashes between Montreal’s police force and the LGBTQ2+ community. It also politicized more than one generation of artists, activists, and party producers who united to fight for necessary change. Sex Garage is also directly linked to the city’s sexually and musically diverse after-hours scene that exploded in the 1990s, as well as its alterna-queer movement of the 2000s.

Through visiting, working, and DJing in Montreal over the years, I’ve learned a lot about the event and its impact on the city’s queer community. Almost 27 years later, its story remains noteworthy, despite not being as well-known outside of provincial borders. Here, scene-makers who organized, participated in, or were later influenced by Sex Garage reflect on its legacy and how the lessons learned from the aftermath are all-too-relevant in today’s political climate.

WHAT CAME BEFORE

Sex Garage was far from the first time that Montreal police were uninvited guests at a gay soirée.

“It’s historically been a very difficult relationship between police and the gay community here,” says playwright and publicist Puelo Deir, who also co-founded the city’s original Pride festival, Divers/Cité. “When there was a relationship, it was because the cops decided to come into a bar and either shut it down for the night or check what was going on, often accusing the bar of being a common bawdy house.”

“In the late 70s, cops raided west end leather bar Truxx. They put guys in jail, put their names in newspapers, and people were charged with sex crimes. I believe it was part of Mayor Jean Drapeau’s attempt to clean up downtown. Drapeau had no tolerance for gays.”

Deir, who grew up moving between Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa, made the former home in the 80s because he was drawn to its French and Latin culture, as well as the city’s reputation for less conservative nightlife. He enjoyed the mixed crowds that came together at loft parties more than the separations that existed in the Gay Village.

“The Village had migrated from the west end of the city to the east end, where we know it to be today,” Deir describes. “The bars were quite segregated; there were men-only bars, and many of them didn’t even allow drag queens in. The loft and warehouse parties—the illegal after-hours—were a way for French and English, men, women, trans and drag to co-habitate outside of the Gay Village structures.”

According to many, the most adventurous of those loft parties were presented by filmmaker and artist Nicolas Jenkins, aka Sterile Cowboys & Co. Born in Peru and raised largely in Canada, Jenkins had studied at the Ontario College of Art before leaving Toronto for New York. There, he worked at influential nightclub Area as a busboy then projectionist, and fell in love with the underground house music heard at clubs like Paradise Garage.

In 1987, Jenkins moved to Montreal. Soon after, he began to produce parties every two-to-few months. He selectively handed out flyers at gay bars, straight clubs, punk venues, and other spaces. The parties quickly grew to attract hundreds.

“It was an influence from Area to try and do something different every time,” explains Jenkins. “There would be a concept, which I’d incorporate into the flyers, and projections, and the music was house. The music scene in Montreal was really suffering at the time. The gay clubs played incredibly commercial music; house was only played in some black clubs, but they were not so welcoming of gay people. The gay scene was also incredibly segregated and homophobic in the sense of being very hostile to drag queens, to feminine gay men, and women were only allowed in the men’s clubs once a month, if that.”

“Coming from New York where the best clubs were incredibly mixed—you had every age, every class, rich people, poor people, people from the hip-hop scene, from the new wave scene,” he says. “That, to me, was the perfect formula for a great event. That’s what I tried to introduce with my parties.”

SEX GARAGE: THE PARTY & PROTESTS

Sex Garage was a one-off party held in the same warehouse building in the city’s Old Montreal district that local bands had rehearsal spaces in. The isolated location was ideal for the vibe that Jenkins would provide that hot July night in 1990.

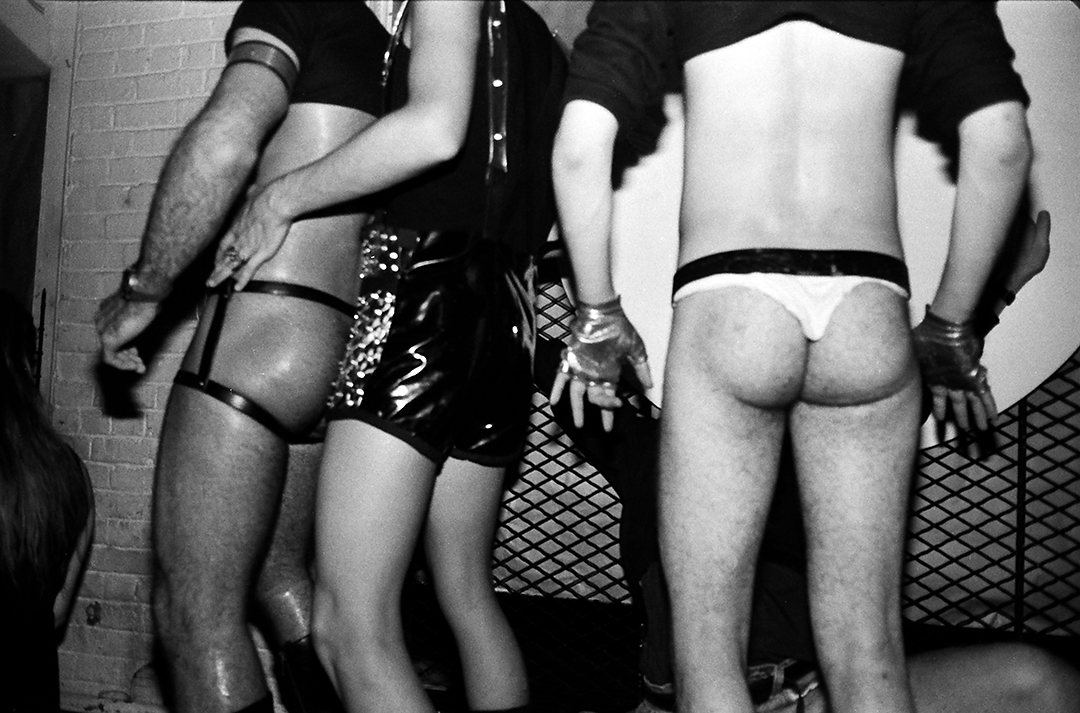

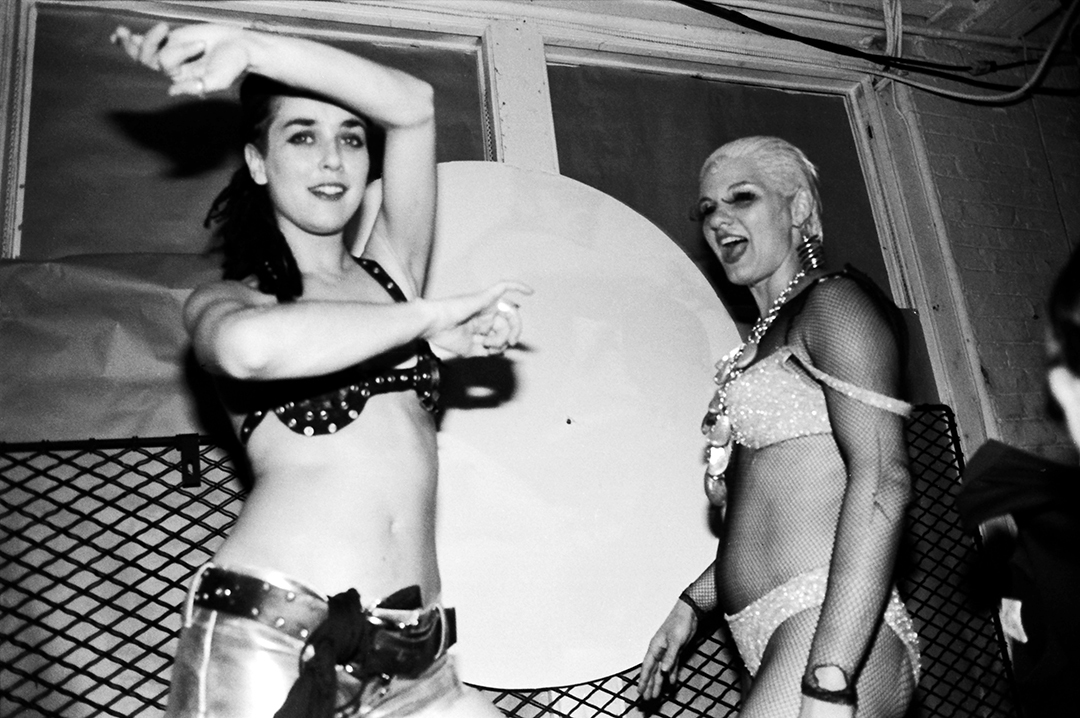

“I had hired a stripper-contortionist who performed and then, as the party picked up, I had go-go dancers. All of the parties had projections—a lot of them sexual in nature, mainly vintage porn. There was nudist porn, straight porn, a lot of gay stuff,” he recalls. “That was when the whole AIDS crisis was happening and I was trying to bring sex back into going out, trying to be very sex positive, and very poly-sex positive, in the sense of celebrating all forms of sexuality. I was very conscious of including tons of gay and lesbian stuff. I wanted to make it very clear that these were queer parties; that even though everyone was welcome, it was a safe space for queer people.”

Jenkins hired DJs including Peter Lightburn and Tony Desypris—both pioneers in Montreal’s house and garage underground—to play the event, which attracted about 400 attendees. Most were inside when police arrived to investigate around 4am. While the organizer was accustomed to visits from the cops (“About half of my parties got shut down”), their arrival this this night would be disturbingly different.

“I started getting nervous because a lot of people were coming in later than usual and all at the same time,” says Jenkins. “When the police showed up, I got the same treatment I’d received at other parties; they basically said ‘The party is over. Turn on the lights, everyone is out,’ and that was it. From my experience, nothing was different, but the way that people were treated outside was. I witnessed everything from the windows.”

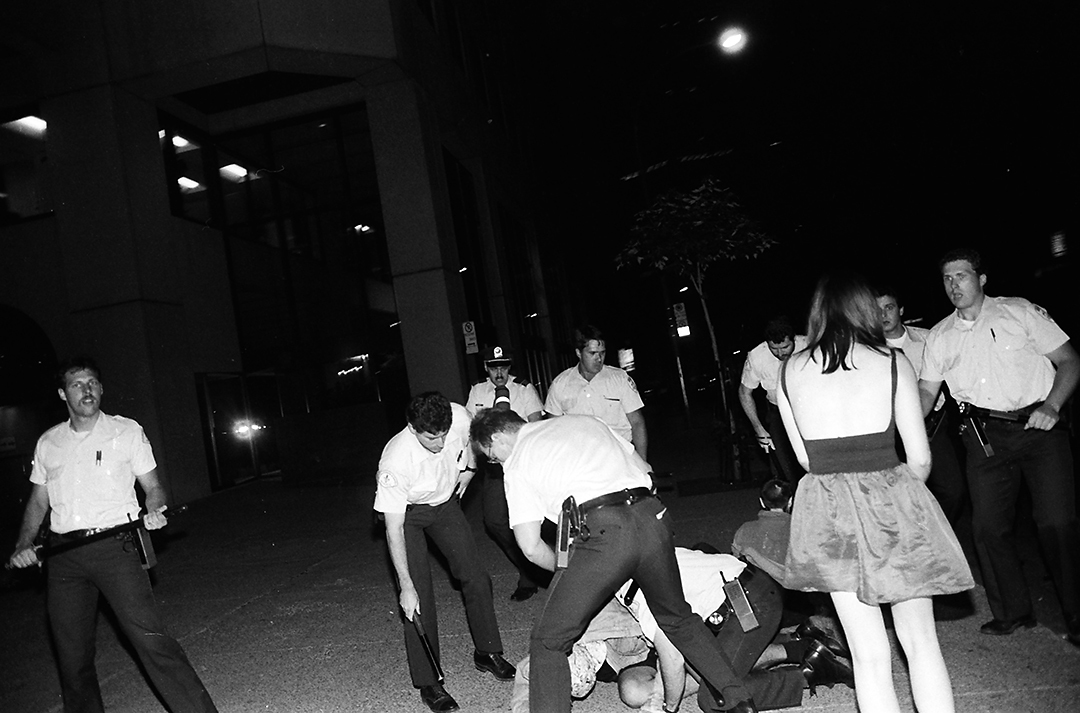

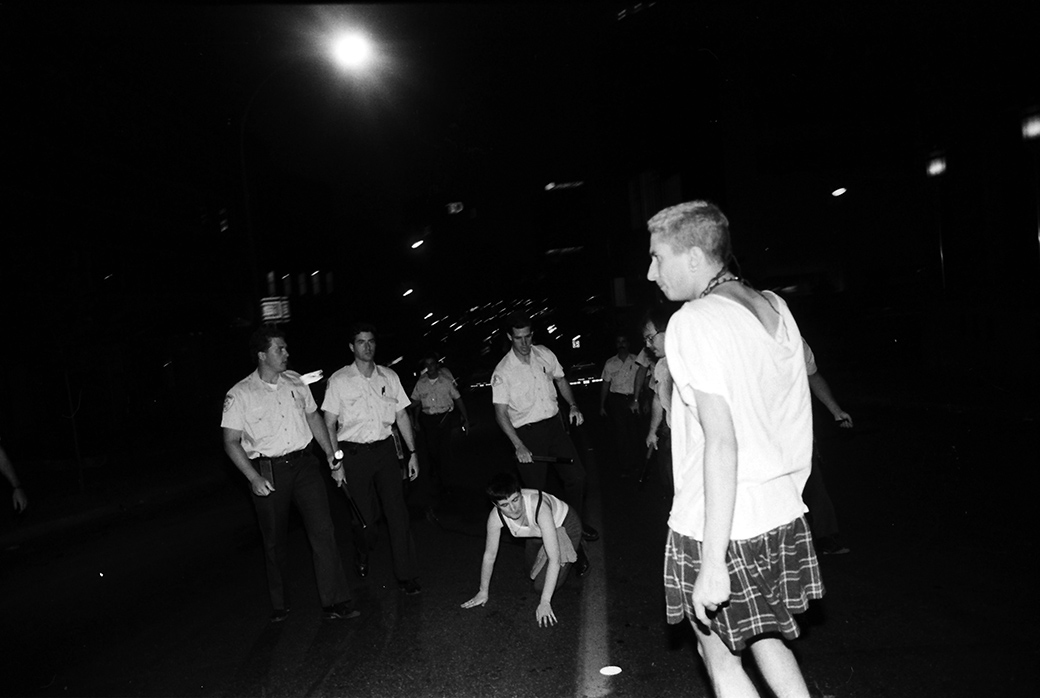

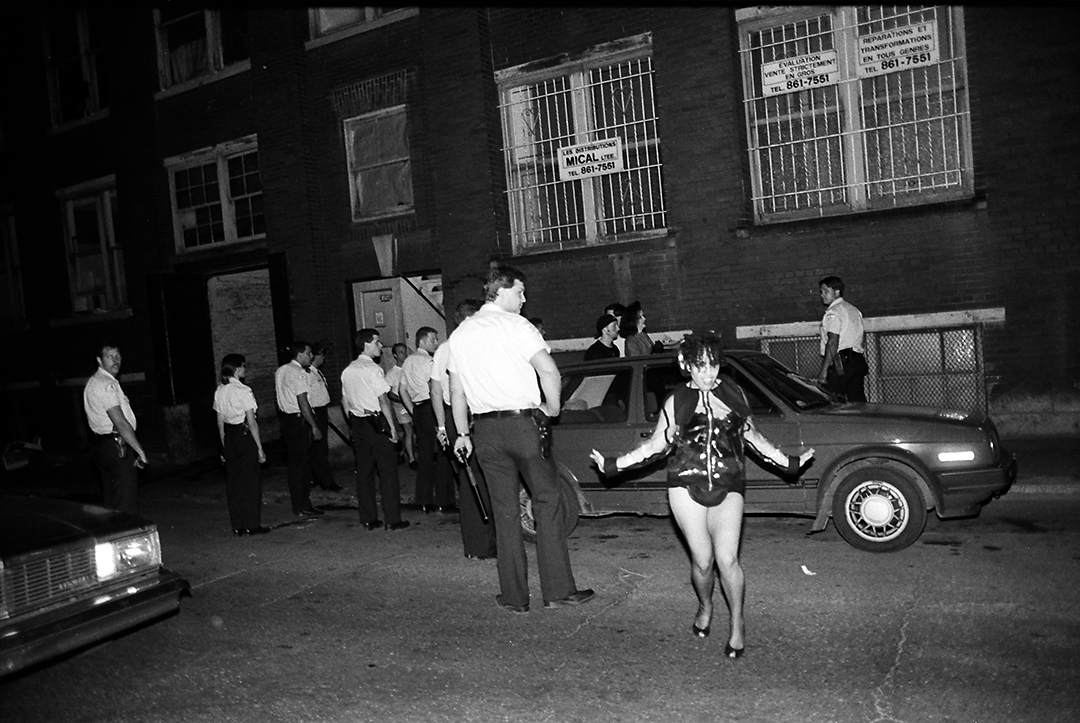

Police “regrouped in battalion formation” as they blocked partygoers attempting to exit. Some cops advanced on the crowd with batons in hand, yelling homophobic insults. The crowd stood firm, volleying back political chants. Some cops removed their badges, and beat party participants.

Photojournalist and writer Linda Dawn Hammond witnessed both the party and police actions with camera in hand. Hammond had moved from B.C. to Montreal in 1982 and became an active participant in its arts and punk communities. Drawn to a “Montreal milieu that was inclusive in terms of gender, sexual orientation, race and language,” she would come to take photos at a number of Jenkins’ events, and was at Sex Garage to document people voguing there. Her photos would capture much more than intended.

“I first heard of the police presence [at Sex Garage] when someone told me that they’d been inside and commanded the organizers to close it down,” she details. “Lights were still dim and the music pounding, so many of us thought it was just a rumour. Then we heard that police were outside the front door, and witnesses from another loft space in the building reported seeing police attack a man from the party, Bruce Buck, who had tried to return to retrieve his coat. The police had taken him out of sight between the building and parked cars, and badly beat him.”

Hammond recorded what came next at length, both in words and photos. Police “regrouped in battalion formation” as they blocked partygoers attempting to exit. Some cops advanced on the crowd with batons in hand, yelling homophobic insults. The crowd stood firm, volleying back political chants. Some cops removed their badges, and beat party participants. Hammond kept shooting, her camera’s flash identifying her location. Despite being knocked to the ground by police, she managed to get her camera and rolls of film to a friend who biked away. These photos later served as evidence of both police brutality and a community that no longer accepted this as a given.

“The cops went to extremes with a new generation that night,” says Puelo Deir, who was at Sex Garage though had left before the raid. “This was a new generation that was out, media-savvy, and that wasn’t afraid of having their names printed. They were also more militant given HIV and AIDS. We were at the apex of mobilizing around that. Also, it was a mixed crowd of people—French and English, gay, straight and trans, bi people, supporters. You had a hodgepodge of partiers, politically motivated people, university-educated people, and a few street thugs that were ready for a fight.”

People mobilized quickly. The very next day, there was a large protest—dubbed both the “love-in” and the “kiss-in”– held outside of downtown police Station 25. This time, mainstream media outlets including La Presse, Montreal Gazette, and CTV Montreal were there to witness what transpired.

“[There were] more than 70 police, clad in riot gear and some with latex gloves to protect themselves from AIDS,” says Hammond, who again took photos. “They surrounded us in a square formation.” “I witnessed that the police beat protesters up in broad daylight, in front of the news media,” adds Jenkins, who attended. “They did it so openly, which to me indicated the extent of their homophobia. They thought that it was okay to do that publicly. Except it backfired. It got so much press attention, and not positive for them.”

“I think the vicious daylight police attack of July 16th, and subsequent arrests, reinforced public support and galvanized resistance,” agrees Hammond, who notes that friends, family and others would gather at later protests to support the gay community. “Sex Garage brought together all these communities that had never co-existed to work together in a way that had never happened before,” says Deir. “They didn’t even go out together in the same places and then, all of a sudden, were confronted with working together.”

WE’RE HERE, WE’RE QUEER, GET USED TO IT

Sex Garage further united a generation already fighting homophobia and issues related to HIV and AIDs.

“The timing was kind of perfect,” says Jenkins. “There was a lot of activism happening in the bigger cities. There was ACT UP and Queer Nation, and a small group of us were already starting to organize those groups in Montreal. People like David Shannon, who used to have a column in the Montreal Mirror, Paula Sypnowich, Blane Mosley, and Douglas Buckley were already starting to be active and political. I think Sex Garage just inspired more people to join.”

Filmmaker Maureen Bradley, then based in Montreal, captured the increased community engagement in a short documentary about Sex Garage titled We’re Here. We’re Queer. We’re Fabulous.

Deir, a self-professed “party boy,” was one of the people to immediately step up. He helped raise funds for Sex Garage-related legal defence by producing a series of events. He and others also formed a range of political-action groups to fight for LGBTQ2+ civil rights in Montreal.

“There was the Table de concertation des gaies et lesbiennes du Grand Montréal, which developed out of Sex Garage, and the group Lesbians and Gays Against Violence,” states Deir. “There were the Quebec Human Rights Commission’s historic 1993 hearings on violence against gays and lesbians. That stemmed out of Sex Garage, and the activists who had started out with ACT UP and Queer Nation, and grew from there. Sex Garage brought queer rights into the public domain in a way that hadn’t happened before.”

He was also inspired to organize the city’s first large-scale Pride march in 1993, Divers/Cité, with co-founder Suzanne Girard. Founded on a strong spirit of protest, a commitment to remember both Sex Garage and those lost to HIV and AIDS, and a shared belief in inclusion, it grew to become Montreal’s biggest Pride event for more than two decades.

“Most of us who were around Sex Garage were also at the origins of Divers/Cité,” says Deir, who remained a co-organizer until 1998. “If it’s contentious or arguable that Sex Garage was Montreal’s official Stonewall, it was my Stonewall. It was important to honor that significant event in Montreal’s queer life.”

THE SOCIAL & SONIC REVERBERATION

Parallel to the political organizing were the parties. The influence of mixed loft parties was felt in many gay clubs that moved to have more inclusive door policies. Nicolas Jenkins was even hired by some clubs, like legendary multi-level Gay Village venue K.O.X., to help broaden the clientele.

He also continued to create large loft parties after Sex Garage, collaborating with Mark Anthony in the 90s. Before he would go on to be one of Montreal’s most successful house and circuit DJs, a teenage Anthony attended Jenkins’ “very cool, very eclectic” parties, and had been “dumbfounded” when he’d learned about the Sex Garage raid on the news.

“Being a straight guy, but mostly hanging out in the gay world, I got to see it through a different lens,” says Anthony. “It was homophobia, straight up. I think Sex Garage made people more aware of what was going on. It opened their eyes, socially speaking.”

Together, the duo produced after-hours parties with “racy invitations, amazing ambiance, décor, and dancers,” according to the DJ. “Our parties were a little bit more trendy, and with more people. We gathered people from all walks of life; we had a black crowd, a gay crowd, the cool straight people, and the downtown people,” he says. “That was exactly our vision of the Montreal utopia.”

Anthony also points out that the police never shut down any of the parties he did with Jenkins. Nor were there any issues with Playground, Montreal’s first legal after-hours club, which operated in the Gay Village from late 1994 into 1997. Anthony was Playground’s Saturday night resident.

“Playground was Montreal probably at its best,” says the DJ. “It was a special time. The music was good, the drugs were good, and it was also phenomenal to see gay people and straight people in an after-hours setting. That was nothing new for us, because we had seen it with our parties, but to then officially witness it in a commercial club—I knew we had hit the next level in Montreal.”

Though it didn’t last long, Playground help set the course for Montreal’s next big legal after-hours club, Stereo, which opened in 1998, also in the Village and also developed with Anthony’s input. Stereo famously drew a very mixed crowd for many years, including on the DJ’s Ritual nights. (He’d later go on to tour the world and today is focused on production.)

Plastik Patrik is another Montreal nightlife icon deeply influenced by attending Jenkins’ parties. At 18, he read about the Sex Garage raid and protests in newspapers. Soon after, he was on Jenkins’ dancefloor.

“Nicolas’ parties were very stimulating—from the music to the visuals, the themes, and the people who attended. When I came across that whole crowd, I really liked the duality between the decadence and the extravagance, and the political awareness,” enthuses Patrik. “I realized that those people who I thought were so damn cool were also involved in some of the protests, and thought ‘Wow—you can do both. You can be cool and political, have this social conscience and advocate for both things.’ It kind of set me up for a lot of what came afterwards.”

Having grown tired of house music in the late 90s, he established himself as an alternative DJ and fronted glam-punk bands including One 976 and Patrik et les Brutes. He took his records, bands and fiercely androgynous self to venues around the city, deliberately making noise in gay bars and seedy punk clubs alike.

Alongside DJs like Bobzilla, Frigid, and Mini, Patrik was at the centre of Montreal’s alterna-queer art and music explosion. They brought rock, electro-clash, and techno to Village clubs like Parking and Sky, and Plateau hotspots including Saphir Bar, where he helmed an eight-year Friday residency. “There were a lot of people sort of pushing in the same direction at that point,” says Patrik. “The scene grew, and that’s where Sex Garage, the Divers/Cité event, connected.”

SEX GARAGE: THE STAGE

As Divers/Cité grew in size, scope, and funding, the festival added more outdoor performance stages. Patrik programmed the Sex Garage stage for most of the 2000s. As with the original party, the stage attracted a pansexual crowd and featured underground sounds.

“It was a kind of tougher, in-your-face sound,” Patrik describes. “It was usually danceable, and it was always energetic.”

The popularity of the Sex Garage stage meant its budget allowed for out-of-town bands like Olympia, Washington’s Gossip, California electro-clash group Gravy Train!!!!, and Vancouver post-punks The Organ, alongside local faves including Lederhosen Lucil, Frigid, the Cherry Persuasion, Duchess Says, Echo Kitty, We Are Wolves, and Cherry Cola. Before they would record for Alien8 and tour alongside bands like Le Tigre, Montreal electro-punks Lesbians on Ecstasy played one of their first shows on the Sex Garage stage.

“It was so fun!” recalls the group’s co-founder and lead vocalist Lynne Trepanier. “We still played with our blue iMac on stage, which was hilarious. Plastik Patrik hosted and there were so many people there. Big corporate shows always feel a bit weird so [the Sex Garage stage] was the best-case scenario for us to play at Pride. Our friend Viviane made us buttons to throw out into the crowd that said ‘I support Lesbian Divorce.’”

Though she had been too young to go to Jenkins’ parties, Trepanier had heard about the original Sex Garage and understood its significance.

“I knew that it was an important moment, and it meant a lot more than just a party space. Then, at Concordia, I took a course about the HIV/AIDS pandemic and Sex Garage was discussed a lot as an impetus to the queer rights movement in Montreal,” she says, who would go on to host three electronic music programs on community radio station CKUT and co-produce a new wave of loft parties.

While the music was different, the goals were similar to those of Jenkins’ a decade earlier. “A group of friends and I started to throw some that were pretty centered around the drum and bass scene, and we were a jumbled mix of gay and straight. Very PLUR. Very celebratory,” adds Trepanier. “I think that the loft parties were a way to create safe space where all were welcome. It was easy to be off the radar back then.”

LESSONS IN ACTION

Today, lessons learned from the likes of the Sex Garage raid are again important to hold close as we witness the steady and vicious rollback of human rights the Trump administration is working to enact, including against LGBTQ2+ people.

“I don’t think Sex Garage is widely known outside of Montreal,” says Jenkins, who moved back to New York in 1994, and has continued to make films immersed in queer culture, including last year’s NYC ballroom and vogue short documentary Walk. “I think a lot of things that happened before the internet get forgotten.”

Thankfully, people like syndicated queer journalist Richard “Bugs” Burnett, scribe for publications including HOUR, Xtra!, and the Montreal Gazette, have written extensively on the subject. The 25th anniversary of Sex Garage was also recognized in 2015 by Fierté—Montreal’s only Pride festival since Divers/Cité folded that same year—with an exhibition of Linda Dawn Hammond’s photos.

“I did not realize it was remembered to that degree,” admits the photographer, who had left Montreal for Toronto 11 years prior. “Some younger people who saw the exhibit and didn’t know about Sex Garage expressed surprise that something like this could have happened ‘back then.’ I hear it’s contentious to some people to refer to Sex Garage as ‘Our Stonewall,’ but I recognize that the history of LGBTQ activism in Montreal changed following this event, and am proud to have been a part of it.”

Sex Garage did more for Quebec LGBTQ human rights than any other event before it. It engaged an entire generation of people to be out and, more importantly, to be politically motivated and change culture and change society.—Puelo Deir

Puelo Deir agrees. “Sex Garage did more for Quebec LGBTQ human rights than any other event before it,” he emphasizes. “It engaged an entire generation of people to be out and, more importantly, to be politically motivated and change culture and change society. I tell kids and people who say ‘Oh we don’t need Pride anymore’ that we have an example right now of why Pride is more important than ever. You have a situation in the United States where they want to destroy all of the gains that we’ve achieved and, as we’re seeing, it can be easily done.”

When asked to comment on the relationship between Montreal’s police force and the queer community today, Deir immediately responds, “Non-existent. We have the queer kids that are anti-cop, and I totally get it. We had the student protests of ‘Maple Spring‘ [2012] and again more recently [2015], where the relationship with the cops showed how not much had changed at all. The cops have never, to my knowledge, participated in the parade with Divers/Cité or the current incarnation of Pride in Montreal. I think there’s still a lot of work to do.”

Deir, who is currently at work on a documentary/theatre piece about male sex work and Canadian prostitution laws, has pointed to what is perhaps the most divisive issue in Canadian queer politics today: how, if at all, police should participate in Pride parades outside of paid on-duty shifts.

This issue came to the forefront when Black Lives Matter Toronto halted last year’s Pride parade to present a list of demands to Pride Toronto. The item on that important list that has received the most media attention—and sparked countless heated debates—is the demand to remove police floats from the parade. Earlier this year, members attending Pride Toronto’s Annual General Meeting voted to accept and implement BLM’s demands. Off-duty police remain welcome to participate in the parade on foot, but not in uniform.

“I think that everything happening in Toronto right now, about Pride and police, is bringing this issue into discussion, where it should be,” affirms Trepanier, who now works as a sound recordist and continues to DJ. “How on earth can people forget so quickly that the police hated us? They may be better at PR, but the police still actually hate on QPOC communities and people live in fear of the police. The cops are not a benign force —they enact racist and homophobic policies all the time. Pride was about fighting back against that.”

This conversation is a crucial one. All people whose lives fall under the LGBTQ2+ spectrum do not benefit equally from the same rights and privileges. Until we do, there is reason to keep marching and protesting.

“It seems to me that what Black Lives Matter did was remind people that Gay Pride is about more than sponsors and dancing and a parade,” observes Patrik. “One thing I definitely learned from Sex Garage is that when you want to bring on radical change, it’s always messy. Change as fundamental as the way that people look at gays or queers, and how the police respect or lack respect, is never done in a polite manner because it’s sort of a punch back.

“I think that’s what Sex Garage was. It was ‘Enough is enough,’” he says. “What came after was a feeling that you could go out and be gay in the world, and the world was ready for it.”

Denise Benson is on Twitter.