Former Vice President Joe Biden entered Wednesday’s debate as the dominant frontrunner in the Democratic primary and a symbol of the party’s establishment, even at a time when its left wing is increasingly powerful.

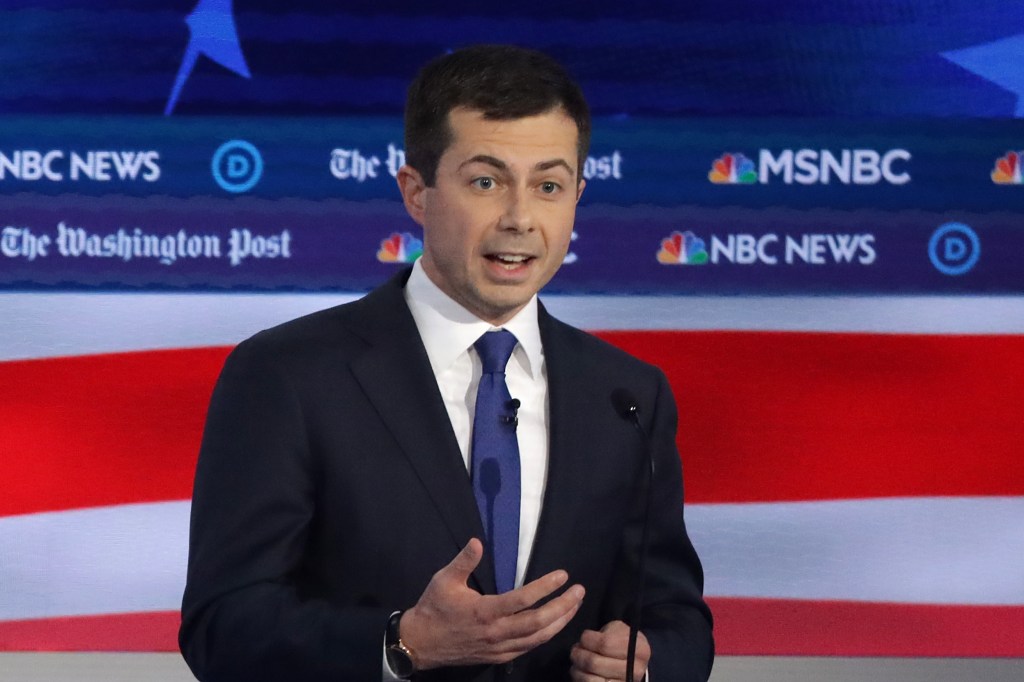

But South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg carried the mantle of moderation. Biden misspoke, rambled, and awkwardly promised to “keep punching” at the issue of domestic violence; Buttigieg displayed tremendous poise, flipped questions about his inexperience into a badge of honorable outsider status, and delivered sunny slogans for a centrist Democratic presidency.

Videos by VICE

Buttigieg is a persuasive speaker, and his performance Wednesday night served as a reminder of why he’s recently skyrocketed to frontrunner in Iowa and near-frontrunner in New Hampshire, despite languishing at a distant fourth in national polls. But the slickness of his presentation often distracted from the blandness of his substance. On a number of occasions, Buttigieg revealed a naive theory of politics that seems bereft of serious reckoning with power or policy.

In his first answer of the debate, Buttigieg referred to President Donald Trump’s conduct as impeachable, but prefaced it with a curious declaration: “The constitutional process of impeachment should be beyond politics.” from start to finish. In other words, Buttigieg’s hope to keep impeachment above the fray of politics is at odds with how the whole thing works.

Buttigieg’s puzzling outlook on how politics works resurfaced later, this time about overcoming Republican resistance during the Obama era. He responded that his plan of “Medicare-for-all-who-want-it,” which would allow people to opt into a government health program option, would “unify the American people,” in contrast to a more sweeping Medicare-for-all plan that would abolish private health insurance.

That analysis seems a bit optimistic. Obamacare was a fundamentally conservative reform plan that was conceived of by a right-wing think tank, previously tested out by a Republican governor, and posed no existential threat to the private health insurance system—and it was still subjected to the most vicious Republican political attacks of the decade. In fact, a crucial part of Obama’s strategy for passing it was dropping the public option: the very kind of plan Buttigieg wants to pass into law.

This is not to say that Buttigieg’s plan cannot be passed. Rather, it’s to point out that when he said he wanted to find ways to “galvanize not polarize” the public, he seems to misunderstand how Republicans, who are likely to hold onto a majority in the Senate in 2020, respond to attempts at moderation and compromise: they scoff at it.

Buttigieg’s remarks about unity echoed an earlier speech in which he promised never to “allow us to get so wrapped up in the fighting that we start to think fighting is the point.” The language was a thinly veiled criticism of his competitors Warren and Sanders, who embrace combative attitudes and see polarization as an intrinsic part of today’s political climate that can be harnessed for the good of the Democrats.

His talk of unity echoed something else too: Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. A key premise for Obama’s initial run for the White House was to revive bipartisan unity and fix Washington by rebuilding trust. Buttigieg’s objection to being polarizing seems to match that sensibility, as does his emphasis on even trying to win people across the aisle even during his own party’s primary. During the debate, he was the only frontrunner to mention Republicans as part of the coalition he’s looking to build.

It bears noting, though, that Obama’s promises of unity didn’t pan out as he expected. His attempts at good-faith negotiation with the opposition were not reciprocated—Senate majority Leader Mitch McConnell explicitly said that making Obama a one-term president was “the single most important thing we want to achieve.” And Democrats constantly agreed to lopsided compromises on bills like Obamacare and the economic stimulus package.

Buttigieg’s talk about breaking the shackles of hyperpartisanship and coming together to save the republic is seductive, but nothing about the way politics has been evolving for decades suggests that it’s a sound strategy. Like Obama, he relies on charisma and optimism to make such a future seem possible. But the hard realities of polarization cannot be vanquished solely by good intentions.

In an age when widespread unity is a political impossibility, fear of being polarizing isn’t just out of touch—it could be an act of self-sabotage.

Zeeshan Aleem is a columnist for VICE. Follow him on Twitter and join his politics newsletter .