Water is the key ingredient for life on Earth, which is why scientists hoping to find aliens on other worlds are particularly interested in its presence. A team of researchers made a huge splash on this front in 2018 by suggesting that radar observations of bright patches under the southern polar cap of Mars were hidden lakes that could potentially provide a habitat for modern Martian microbes, according to a study in Science.

But a trio of new studies throws cold water on these hypothetical subglacial lakes by proposing alternative explanations for the observations, which were captured by the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) instrument on the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter.

Videos by VICE

For instance, one team of researchers demonstrated “that clay minerals known to exist in the south polar region of Mars are sufficient to fully explain the radar observations,” according to a study published on Thursday in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. While these minerals, known as smectites, might rule out the existence of lakes on modern Mars, they corroborate the evidence that the red planet was much wetter billions of years ago.

“We’re not saying lakes are impossible,” said Dan Lalich, a research associate in the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science and second author on the new paper. “We just think that this is much more likely and consistent with other independent observations, whereas with lakes you have to start invoking some more complicated or unique scenarios.”

“I think, at least for now, this smectite hypothesis and the other papers that have come out will be the favored interpretation in the broader community but, as always, that’s not to say they’ll turn out to be definitely right,” he added.

While it is exciting to imagine water flowing under Mars’ south pole, the 2018 study also provoked skepticism among many Mars scientists. The idea of subglacial lakes clashed with estimates of freezing temperatures a mile under the polar cap, creating conditions that are too cold to support liquid water. These incongruities, among others, were eventually explored further at the International Conference on Mars Polar Science and Exploration in Ushuaia, Argentina, in January 2020, just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

The conference kickstarted the batch of new studies that have appeared in recent weeks, along with a few others that are still awaiting publication. One paper, published last month, showed that the bright signals at the south pole are widespread, and often located in areas that appear too cold to host liquid water. Another study, published two weeks later, suggested that clays, metal-bearing minerals, or saline ice at Mars’ south pole could explain the reflective radar signals.

Lalich and his colleagues, including lead author Isaac Smith of York University, have now zeroed in on smectites, a common clay mineral on Earth and Mars, as the possible source of the radiant spots. To back up their hypothesis, Smith simulated chilled smectites to -58°Fahrenheit (-50°C) in the laboratory to simulate temperatures under the Martian south pole, which revealed observational signatures akin to those captured in the MARSIS radar data.

The back-and-forth over these subglacial lakes mirrors a similar discussion about the presence of briny water flows on Mars, a tantalizing idea that also received pushback in later studies. The upshot of all of these disputes is that modern Mars does not seem particularly amenable to the presence of liquid water, or life.

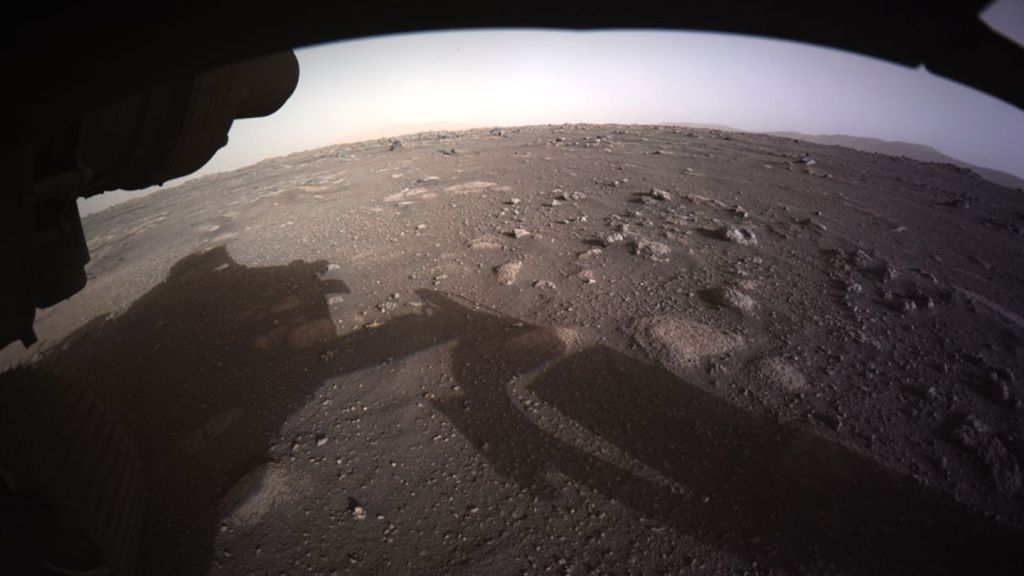

However, the abundance of smectites and other clays on the red planet does corroborate a vast body of evidence that Mars once hosted stable bodies of liquid water in the past. NASA’s Perseverance rover is currently exploring Jezero Crater, an ancient lakebed, in order to collect samples that will be eventually returned to Earth. Life on modern Mars may be a tall order, but scientists hope that Perseverance’s samples will reveal that the red planet was once habitable, and perhaps even inhabited, billions of years ago.

While it can be a “bummer” to cast doubt on the abundance of liquid water on modern Mars, Lalich said, it’s also a necessary step toward a better understanding of this fascinating neighboring world.

“The big lesson here is that when you do have these anomalous observations, you have to be really, really careful about them,” Lalich noted. “Radar is a tool that’s being used on other planets and other moons to do things like detect water.”

“Maybe this is a cautionary tale that getting a detection that looks like liquid water may not uniquely be attributable to liquid water,” he concluded. “It’s something that you just have to be really careful about; you have to really cross your t’s and dot your i’s when you’re trying to make that kind of detection and ideally, you’ll need multiple lines of evidence.”