“A little trash talk is an expected part of competitive multiplayer action, and that’s not a bad thing. But hate has no place here, and what’s not okay is when that trash talk turns into harassment.” This was Microsoft’s attempt to draw a line between good-natured put-downs and more toxic forms of online interaction in a May 2019 update to its Xbox community standards. The document also helpfully outlines examples of acceptable and unacceptable trash talk. For instance, “That sucked. Get good and then come back when your k/d’s over 1″ receives the official Microsoft seal of approval. But you’ve stepped over the line if you instead suggest, “You suck. Get out of my country — maybe they’ll let you back in when your k/d’s over 1.”

Flash back to 2002, however, and Microsoft’s marketing campaign to promote Xbox Live’s launch told a very different story. In one print advertisement, a photo of a disaffected young man with a controller in his hand is accompanied by a caption claiming that an Xbox Live opponent “wanted to meet me so he could see the face of failure.”

Videos by VICE

Another 2002 ad asks, “Does ruining someone’s day make you do the dance of joy?” A promotional video from the same era features a player sneering into her headset, “You guys are so pathetic. You chafe my ass!” Sony was in on the act, too. A 2002 ad hyping the debut of the PlayStation 2’s online functionality encouraged players to “reach out and smoke someone,” while highlighting the ability to trash talk opponents as an essential feature of the new service.

These ads, along with others from the era, point us toward an uncomfortable truth: Companies like Microsoft and Sony frequently marketed toxicity as a key selling point for their new online gaming platforms. This is a puzzling strategy from the vantage point of 2020, a time when toxicity is practically synonymous with online gaming and too often spills over into real-world harassment. Perhaps these campaigns were eerily prescient in anticipating the downward spiral of gaming culture. Or maybe these edgy advertisements modeled the exact brand of toxicity that the same companies are now struggling to curb.

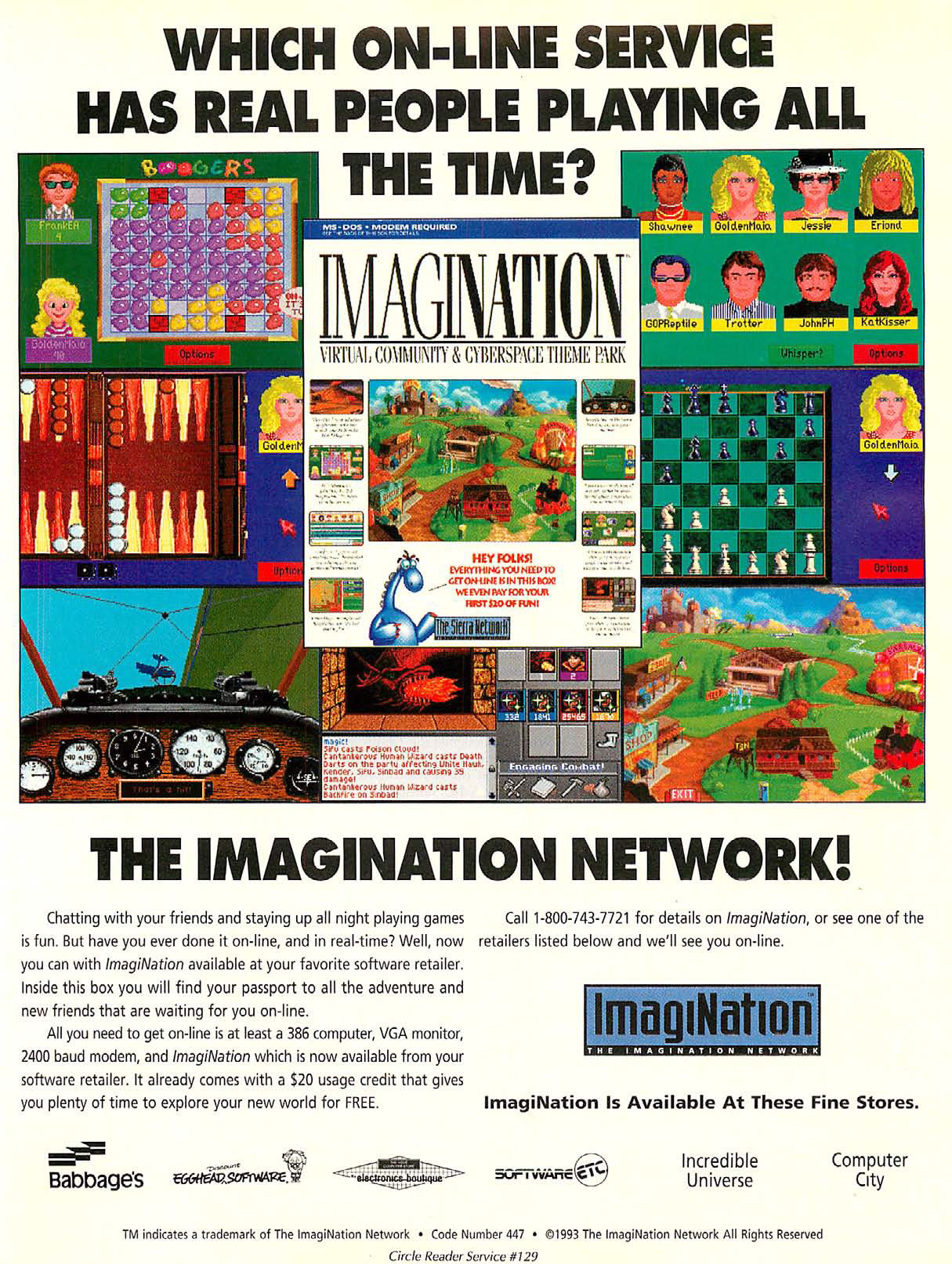

It wasn’t always this way. Ads for online platforms that predated the modern internet — services like CompuServe and Prodigy — emphasized the potential of these technologies to bring people together as opposed to presenting them as platforms to trash talk strangers anonymously. A low-baud modem was your ticket to making friends with people from around the world who shared any number of interests, including games. The Sierra Network, launched by Sierra On-Line in 1991 and later rebranded as the ImagiNation Network, promised all the wholesome fun of “chatting with your friends and staying up all night playing games” on “the network that has the whole country talking.” Even ads for TSN’s racier LarryLand, inspired by Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry series, remained decidedly tame.

When did the shift toward commodifying and marketing toxicity occur? In many ways, the late 1990s and early 2000s were a defining period for video games — the crucible in which modern gaming culture was forged. It was an attitude-driven era characterized by the intense competition and skull-cracking trash talk of the ascendant first-person shooter genre. Take this copy from a 1997 ad for Quake, showcasing the game’s nail gun: “Player 2 feels the sting of raw metal parting his skin and fatty tissue. Player 2 hears the grinding of his sternum as the spike passes through with ease. Player 2 lurches forward as rusty steel hollows out his chest cavity, bursting his inner organs. Player 1, despite himself, smiles.” Scratchy fonts, violent imagery, and an emphasis on pwning n00bs were de rigueur for ads from this period. Lest we forget, it’s the same era that produced the infamous “John Romero’s about to make you his bitch” Daikatana ad in 1998.

Other advertisements cut out the middle man altogether and simply trash talked potential customers directly. “It knows you like running off-tackle on third and short,” taunts a 1999 print ad for NFL 2K on the Sega Dreamcast. “Obstinate little tool, aren’t you?” Another ad for Sonic Adventure boasts, “Sonic has a new light speed dash. Too bad your lame-ass reflexes are the same.”

At the same time, a growing emphasis on hardware specs gave rise to a gaming “hot rod” culture obsessed with dominating opponents through technological superiority. The console wars of the early to mid-’90s had instilled a fierce sense of brand loyalty in gamers — and with it, the fetishization of bits, bytes, MIPS, pings, color palettes, polygons, frames per second, and any number of other quantitative measures of gaming supremacy. Being a gamer meant having the latest and greatest hardware, and the true elite were dumping thousands of dollars into souping up their PCs. After all, as a 1999 ad for 3dfx graphics cards reminds us, “There are two kinds of gamers in this world. The ones who still play on consoles. And the ones who’ve actually seen breasts.”

Speaking of fragile masculinity, the turn of the millennium is also a period when magazines, marketing campaigns, conventions, and the games themselves consistently reinforced the hardcore “boys only” mentality we know all too well today. This was a time when booth babes still walked convention floors. Ads from the era frequently relied on sexualized images and lazy masturbation-adjacent puns to sell games to a presumed audience of straight, adolescent boys. Meanwhile, magazines like PC Accelerator and PC Zone ran contests for readers to win a date with Lara Croft — or at least whoever was currently under contract with Eidos to portray Lara at industry events.

Given this broader cultural context of the late 1990s and early 2000s, it’s no surprise to see various forms of aggression, over-competitiveness, and hypermasculinity creep into advertisements for online gaming platforms. In fact, their toxicity hardly seems out of place considering the zeitgeist of the moment.

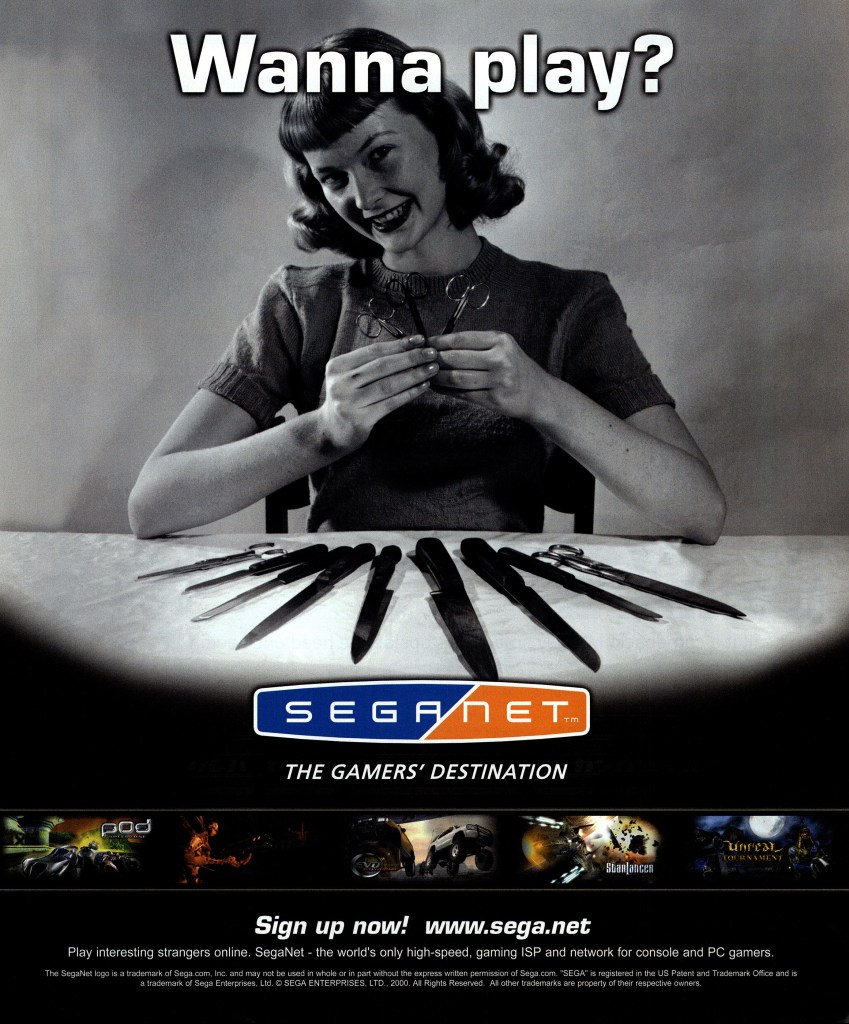

It’s around this time that Sega emerged as an industry thought leader with provocative advertisements for Heat.net, its online PC gaming platform. A 1998 ad for the service includes a disturbing testimonial from a presumably fictional Heat.net player: “I used to take out my bullets, and on each one I would write the name of each person on my bus. Then a friend showed me I could purge my violent urges in Net Fighter on Heat.net against other people. Thanks to Heat, the people on my bus will never know how close they came.”

Sega explored this theme across several Heat.net ads, coining the term cyberdiversion theory and suggesting if we “satisfy our primal violent urges on the Net, we won’t have to hurt people in reality.” After all, who needs to talk through their issues with deep-seated rage with a therapist when there’s Heat.net? As another Heat.net advertisement from 1997 reminds us, “CYBERBULLETS CAUSE NO PAIN!!”

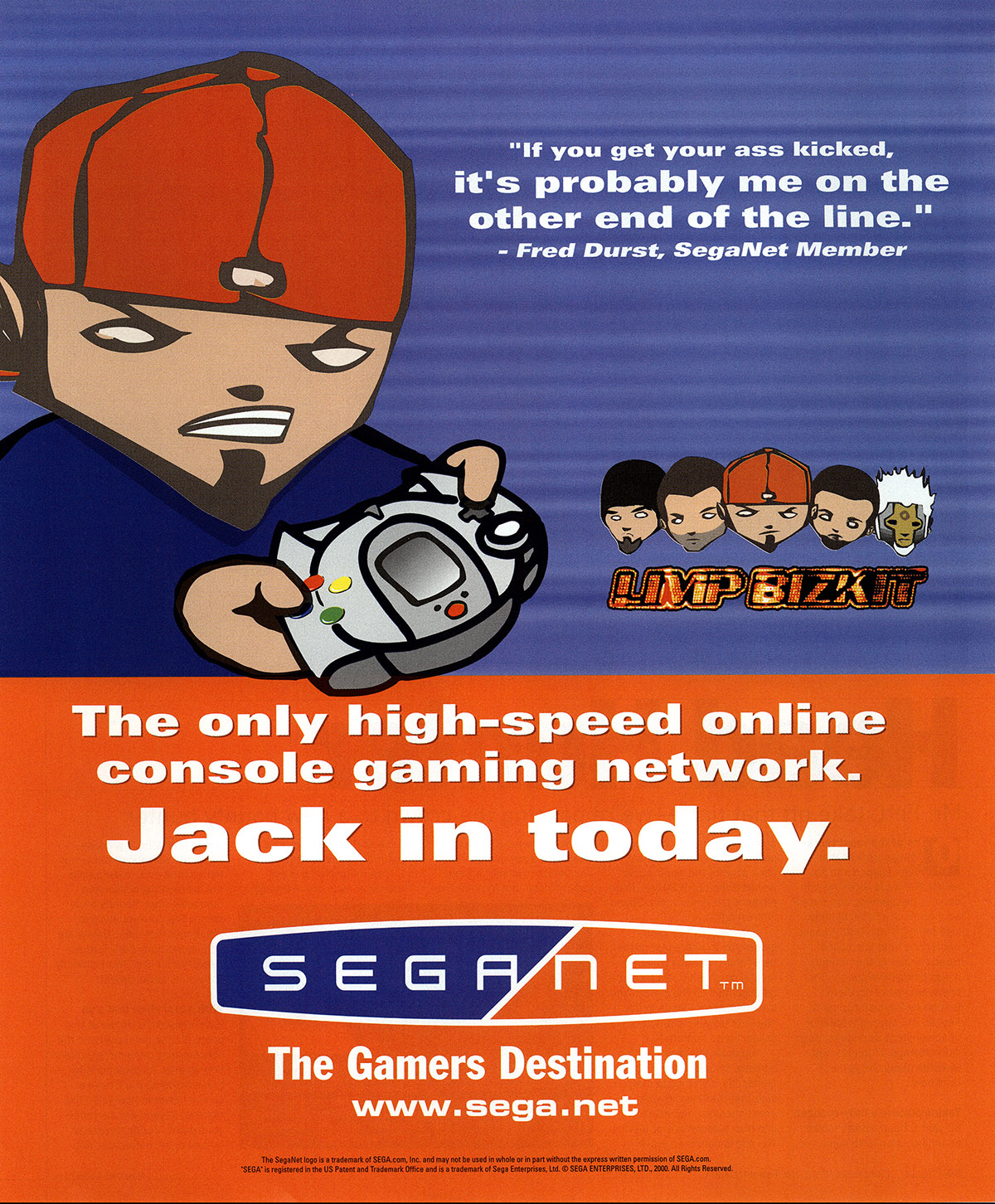

When Sega launched the Dreamcast launched as the first console with a built-in modem, the company turned to none other than rap-rockers Limp Bizkit to promote their SegaNet online gaming service. In a 2000 print ad, what can only be described as a chibi cartoon version of frontman Fred Durst assures the reader, “If you get your ass kicked, it’s probably me on the other end of the line.”

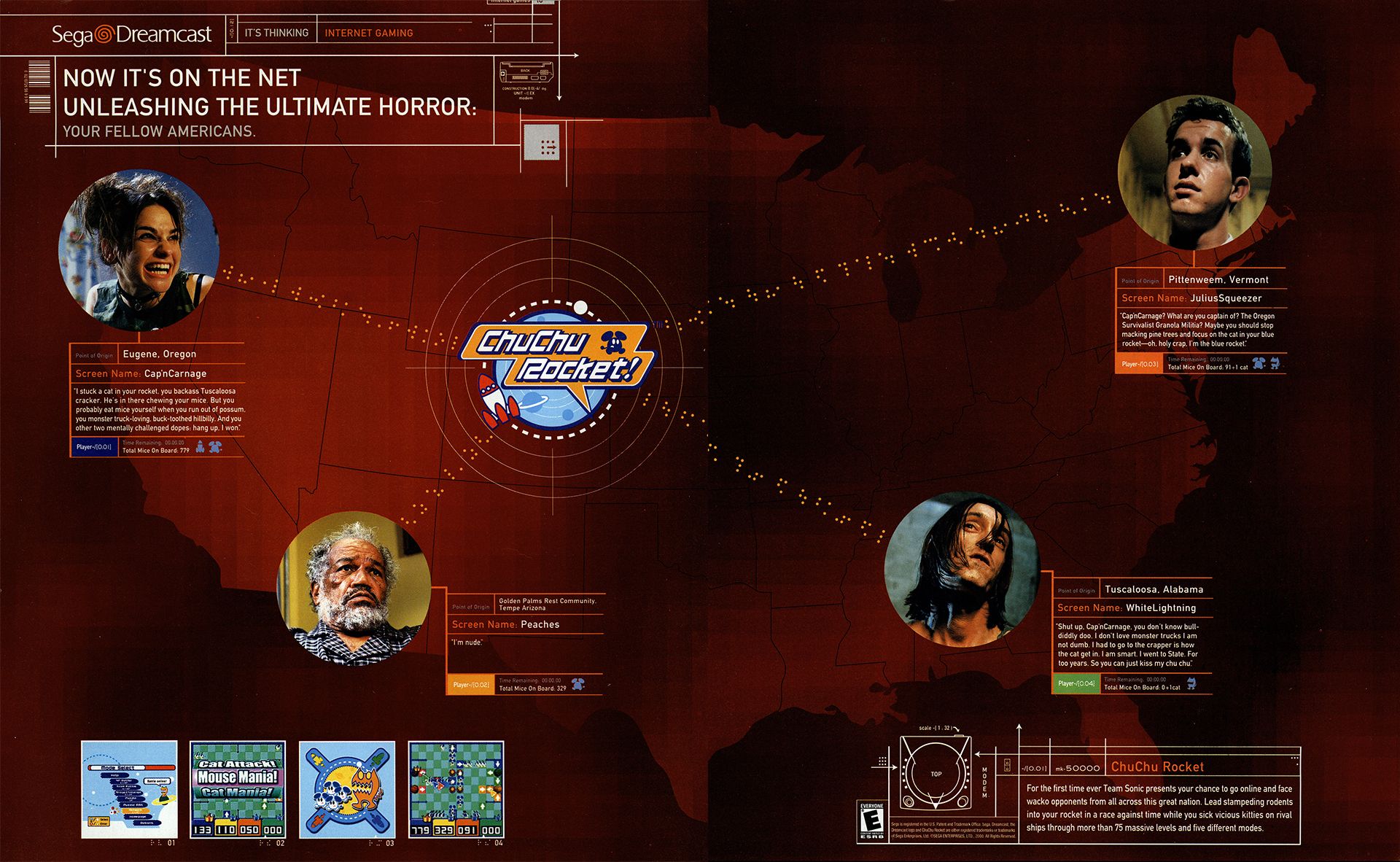

It’s an advertisement for Sega’s ChuChu Rocket!, a puzzle game about mice evading cats by escaping on rocket ships, that showcases the very worst of this toxic marketing. The ad, which hit magazines in mid-2000, depicts a player named Cap’n Carnage unleashing the following diatribe on her rivals: “I stuck a cat in your rocket, you backass Tuscaloosa cracker. He’s in there chewing your mice. But you probably eat mice yourself when you run out of possum, you monster truck-loving, buck-toothed hillbilly. And you other two mentally challenged dopes. Hang up, I won.”

This rant would almost certainly earn a ban from most reputable gaming platforms today, but twenty years ago, Sega considered it a perfectly reasonable way to sell the first online Dreamcast game to potential customers. While Microsoft and Sony never stooped quite so low in promoting their multiplayer platforms, we nevertheless see similar themes of toxicity and harassment at play in their early ads.

Sure, readers might have flipped past these toxic ads to get to GamePro‘s exclusive Syphon Filter 2 strategy guide or EGM‘s preview of the latest WWF game, but they saw them. And, as is so often the case, the ads in question are about more than just selling a product or a service. They teach potential customers how they will use the product, how they should feel about it, and where it will fit into their lives. The apparent lesson here? These online services are designed, at least in part, for verbally harassing strangers from behind the safety of an anonymous handle. As the ChuChu Rocket! ad boasts, Sega and its industry counterparts had unleashed the ultimate horror: your fellow Americans.

Of course, all of this suggests a fundamental chicken-or-egg problem. Did companies like Sega, Microsoft, and Sony identify a population of hyper-competitive, angry gamers and market their online services toward them, or did the marketing of these platforms model an acutely toxic mode of interaction that gamers then seized upon and imitated? The likely answer is that the two are mutually reinforcing. The toxic marketing campaigns wouldn’t have existed without the audience, but that doesn’t mean the ads didn’t continue to shape that audience once they were out in the wild.

Regardless of which came first, what’s certain is that the major companies began to steadily back away from these edgy marketing strategies by the mid-2000s. Of course, by that point, ill-mannered 12-year-olds yelling sexist, racist, and homophobic threats at rivals during online play had already attained meme status. In turn, when the Xbox 360 launched, Xbox Live ads were reminiscent of a bygone era: “Distance tears friends apart. Xbox Live brings them together.” Similarly, marketing for the PlayStation Network would eventually focus on themes of bringing gamers together, downplaying trash talk and harassment as value propositions.

We also see this shift reflected in the community standards adopted in recent years by companies like Microsoft and Sony. The PlayStation Network urges its members, “Be patient and considerate. Be kind. Remember you were new once too. You can help make someone’s early gaming and community experiences good ones.” Today, Xbox Live encourages gamers to “be yourself, but not at the expense of others.”

Yet, at a time when harassment remains a pervasive and very real problem in gaming culture — particularly for already-marginalized members of the community — the aggressive behavior modeled in these early advertising campaigns offers a window into how we got here in the first place. We may think of toxicity as a bug in 2020, but two decades ago, game companies were selling it as a feature.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshot: SEGA -

Screenshot: Konami Digital Entertainment -