This article appeared in the April issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

On February 21, 2014, 49 years to the day after Malcolm X’s earthly form fell to assassins’ bullets in Harlem, Chokwe Lumumba, the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, came home to find the power out. The outage affected only his house, not any others on the block. He phoned friends for help, including an electrician, an electrical engineer, and his longtime bodyguard—each in some way associated with his administration. They couldn’t figure out the problem at first. They called the power company, and waited, and as they did, they talked about the strange notions that had been circulating. At the grand opening of Jackson’s first Whole Foods Market a few weeks earlier, a white woman said she’d been told at her neighborhood-association meeting that the mayor was dead. He’d been coughing more than he should’ve maybe, and his blood pressure was running high, but he was very much alive. He gave a speech at the grocery store that day.

Videos by VICE

In a time of outcry for black lives across the United States, Lumumba had come to office in a Southern capital on a platform of black power and human rights. He built a nationwide network of supporters and a local political base after decades as one of the most radical, outspoken lawyers in the black nationalist movement.

Earlier that February, Lumumba had given an interview to the progressive journalist Laura Flanders, host of GRITtv. Flanders pressed him on his goals on camera, and the mayor was more forthcoming than he’d been since taking office that previous July. He discussed the principle of cooperative economics in Kwanzaa, Ujima, which guided his plans for upending how the city awarded its lucrative infrastructure contracts; he wanted to redirect that money from outside firms to local worker-owned businesses. He also spoke of the idea of the Kush District, starting with 18 contiguous counties with large black populations around Jackson, which he and his closest allies wanted to establish as a safe homeland for African American self-determination. Jackson was to be its capital. Implied in this kind of talk was a very tangible transfer of power from the white suburbs to the region’s urban black majority.

At the time, Black Lives Matter was still nascent, more a hashtag than an on-the-ground movement, and DeRay Mckesson—the activist now running for mayor of Baltimore—was still working for the Minneapolis Public Schools between sending off tweets. But those paying attention were coming to see Jackson as a model, the capital of a new African American politics and economics, a form of resistance more durable than protest.

Four days after the outage at Lumumba’s home, he phoned his 30-year-old son, Chokwe Antar Lumumba. He felt tightness in his chest. Chokwe Antar, an attorney like his father, was in court, but he rushed over to the house, eased his father into the car, and drove him over Jackson’s cracked and cratered roads to St. Dominic Hospital. There were tests, and there was waiting. Nurses brought Lumumba into a room for a transfusion around 4 PM. They weighed him. After they finished, he leaned back on the bed, cried out about his heart, shook, trembled, and lost consciousness. Less than eight months after he had taken office, Lumumba was dead.

As word of what had happened began to spread through city hall, Kali Akuno made calls. Akuno had been one of the mayor’s chief deputies. He set in motion the local and national security protocol of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, the organization to which he, Lumumba, and many of the others in the administration belonged. He saw clerks rummaging through the mayor’s office, and downstairs the city council was already jockeying to fill the power vacuum. The administration, together with Akuno’s job, was already all but over.

“I’m glad he’s dead,” Akuno remembers hearing someone say the day Mayor Chokwe Lumumba died. “I don’t know what the hell he thought he was doing. He was trying to turn this place into Cuba.”

That evening, Akuno himself started feeling something strange in his chest. He’d been having heart problems of his own, a clotting issue. He checked himself into St. Dominic near 10 PM and was taken not far from where the mayor’s body lay. As Akuno waited to be seen for whatever was happening in him, he heard voices down the hall.

“I’m glad he’s dead,” Akuno remembers hearing. “I don’t know what the hell he thought he was doing. He was trying to turn this place into Cuba.” There is a way of doing things in Mississippi, and Lumumba wasn’t playing along. There are lines you don’t cross, and he was crossing them. One county supervisor wondered aloud on TV what a lot of black people in Jackson were thinking: “Who killed the mayor?”

Louis Farrakhan helped pay for an autopsy by Michael Baden, who had also performed autopsies on Michael Brown in Ferguson and the exhumed body of Jackson’s most famous martyr, Medgar Evers. Supporters had their suspicions of foul play, but the cause of death was an aortic aneurysm, likely enough a consequence of the mayor’s tendencies for overwork and undernourishment. He had been trying harder than was healthy to make the most of the opportunity, to do as much as he could with the time he had left.

As Akuno, off camera, watched Lumumba give his interview with Flanders that February, he felt like his boss was ready to stop playing nice with the Establishment, as he had been so far. The honeymoon was over; the gloves were coming off.

“Mayors typically don’t do the things we’re trying to do,” Lumumba said. “On the other hand, revolutionaries don’t typically find themselves as mayor.”

The commercial building that once housed the Malcolm X Center for Self Determination on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive has fallen into disrepair.

At the center of Jackson’s civic district, Mississippi’s former capitol building looms over Capitol Street, which has been subject to a variably successful renovation effort seeking to replicate the urban revival that has lately been sweeping hollowed-out cities across the country. Intersecting Capitol Street to the north, the segregation-era black business district, Farish Street, now stands nearly empty. Historical signs are more plentiful than pedestrians. The Old Capitol Museum presents slavery and Indian removal—the city was named after Andrew Jackson, in gratitude for his role in the latter—as quandaries to be pondered rather than obvious moral disasters. After all, these were law; there were treaties and contracts. The same could also be said of the predatory mortgages that, in the Great Recession, wiped away what gains civil rights had brought to African American wealth, especially in places like Jackson.

Capitol Street changes abruptly after crossing the railroad tracks on the west end of downtown as it heads toward the city zoo. Lots are empty and overgrown, right in the shadow of the refurbished King Edward Hotel. Poverty lurks; opportunity for renewal beckons. And right there, at the gateway of this boarded-up frontier, is a one-story former day-care building newly painted red, green, and black: the Chokwe Lumumba Center for Economic Democracy and Development. Standing guard against the gentrification sure to come, this has become the most visible remnant of the mayor’s four-decade legacy in the city.

Lumumba first arrived in Mississippi when he was 23 years old, in 1971. He had been born Edwin Finley Taliaferro in Detroit, but like many who discovered black nationalist movements in the 1960s, he relinquished his European names and took African ones—each, in his case, with connotations of anti-colonial resistance. While at Kalamazoo College, in southwest Michigan, he joined an organization called the Republic of New Afrika (RNA). Its purpose was not to achieve integration or voting rights, but to establish a new nation in the heartland of US slavery, one where black people could rule themselves, mounting their own secession from both the Northern and Southern styles of racism alike. This quest was, to its adherents, a natural extension of the independence struggles then spreading across Africa.

Local authorities did not prove welcoming. That August, the RNA endured a shootout at a house they were occupying in Jackson. Police officers and FBI agents came armed with heavy weapons and a small tank; the resulting confrontation left an officer dead. Lumumba himself wasn’t present that day, but supporting his comrades kept him in Jackson a few years longer. A 1973 RNA document in the archives of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission—the state’s segregationist Gestapo—records him as the republic’s minister of justice. The document calls for reparations, in this form: “We are urging Congress to provide 200 million dollars to blacks in Mississippi for a pilot co-op project to make New Communities, jobs, training, fine free housing, and adequate food and health for thousands.”

Lumumba soon returned to Detroit, where he graduated from law school at Wayne State University in 1975. Malcolm X wished he could become a lawyer; Lumumba’s aspiration, he’d later tell his son, was to be the kind of lawyer Malcolm X would have been. He defended Black Panthers and prison rioters. For Mutulu Shakur—who was facing charges of bank robbery, murder, and aiding the jailbreak of Assata Shakur—Lumumba unsuccessfully argued that Shakur was entitled to the protections of the 1949 Geneva Convention as a captured freedom fighter. (He would later also defend Mutulu’s stepson, the rapper Tupac Shakur.) He became renowned to some, and notorious to others. A federal court in New York held him in contempt for referring to the judge as “a racist dog.” Then, in 1988, he persuaded his wife, Nubia, a flight attendant, to move with their two children back to Mississippi. He wanted to continue what he and the RNA had started years before.

The change that came over Jackson after Lumumba’s first sojourn in the 1970s was a cataclysmic but also entirely familiar story of American urban life. (“As far as I am concerned, Mississippi is anywhere south of the Canadian border,” Malcolm X once said.) The advent of civil rights inclined most of the city’s white residents to flee for the suburbs, while maintaining their hold on political power and the economic benefits of city contracts. To many of them, the city’s subsequent decline was a case in point. To Hollis Watkins, a local civil rights hero, the story of the city’s transformation after white flight was simple: “intentional sabotage.”

Lumumba had helped found the New Afrikan People’s Organization, in 1984, and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement grew out of that in 1990. MXGM, whose first chapter was in Jackson, set out to bring black nationalism to a new generation of activists; adults organized and strategized, while kids joined the New Afrikan Scouts and attended their own summer camp.

Safiya Omari, Lumumba’s future chief of staff, came to Jackson in 1989. At rallies, they chanted the old RNA secessionist slogan, “Free the land!”—three times, in quick triplets with call-and-response—followed by, in dead-serious unison, its Malcolmian addendum, “By any means necessary.” Their names and message were foreign to local black folks, and scary to many whites, but as years passed, they became part of the landscape.

After Lumumba’s death, Kali Akuno became the movement’s de facto leader and spokesman.

Since Lumumba’s passing, Kali Akuno has become the chief spokesman for what remains of their movement. As I sat with Akuno at his makeshift desk at the Lumumba Center’s large multipurpose room last summer, he described his world as a confluence of “forces.” In a generation whose radicals tend toward impossible demands and reactive rage, he is the rare strategist. He thinks in bullet points, enumerating and analyzing past mistakes as readily as future plans, stroking the goatee under his chin as his wide and wandering eyes look out for forces swirling around him.

Akuno came of age in California—Watts of the 1970s and 80s—immersed in the culture of black pride and power, descended from Garveyites and New Afrikans. “Akuno” came later in life, but his first name was Kali from birth. People he grew up around talked about cooperative economics, about businesses controlled democratically by the people they serve. They talked about Mondragón, the worker-owned conglomerate co-op in the Basque Country that arose under the thumb of the Franco dictatorship. In college at UC Davis and after, Akuno drifted from one experiment in cooperative living and organizing to another. After Lumumba and his comrades founded MXGM, Akuno gravitated to its Oakland chapter. He would become one of the organization’s chief theorists.

Hurricane Katrina brought him down to the South. When it became evident how the storm had devastated black neighborhoods of New Orleans, and the government response only made matters worse, MXGM mobilized. Lumumba’s daughter Rukia, then in law school at Howard, began flying down every chance she could to organize volunteers. Akuno moved from Oakland and took a position with the People’s Hurricane Relief Fund.

“We were trying to push a people’s reconstruction platform,” said Akuno, “a Marshall Plan for the Gulf Coast, where the resources would be democratically distributed.” But mostly they had to watch as the reconstruction become an excuse for tearing down public housing and dismembering the public schools. It was not rebuilding; it seemed more like expulsion.

“Katrina taught us a lot of lessons,” Rukia Lumumba said. The group started to think about the need to control the seats of government, and to control land. “Without land, you really don’t have freedom.”

Lumumba proposed a “critical break with capitalism” through three concurrent strategies: assemblies to elevate ordinary people’s voices, an independent political party accountable to the assemblies, and publicly financed economic development through local cooperatives.

Akuno and MXGM’s theorists around the country began working on a plan. What they developed would become public in 2012 as The Jackson-Kush Plan: The Struggle for Black Self-Determination and Economic Democracy, a full-color, 24-page pamphlet Akuno authored, with maps, charts, photographs, and extended quotations from black nationalist heroes. It calls for “a critical break with capitalism and the dismantling of the American settler colonial project,” starting in Jackson and Mississippi’s Black Belt, by way of three concurrent strategies: assemblies to elevate ordinary people’s voices, an independent political party accountable to the assemblies, and publicly financed economic development through local cooperatives. Each would inform and reinforce the others.

By 2008, the scheming led to talk of running a candidate. MXGM had been organizing in Jackson for almost two decades, and it had a robust base there. Akuno suggested that MXGM should run Lumumba and begin training Chokwe Antar—who was then finishing law school in Texas—to run for office in the future. Both father and son were reluctant, but Lumumba came around.

In 2009, he ran for a city council seat in Jackson, and with the help of MXGM’s cadres and his name recognition as an attorney of the people, he won. On the council, he cast votes to protect funding for public transit and to expand police accountability. But it became clear that, in Jackson, the real power—in particular, power over infrastructure contracts—lay with the mayor’s office. Those contracts were still going largely to white-owned firms in the suburbs. Black people had long been the majority of Jackson’s population, but the MXGM felt its land wasn’t really free until it benefited financially, too.

Few among Jackson’s small, collegial elite bothered to notice the Jackson-Kush Plan when Lumumba ran for mayor in 2013. He was just one in a crowded pool of candidates. And the plan was still little more than a series of ambitions. The co-ops didn’t exist; the assemblies, when they actually happened, were small and populated mostly by true believers. Yet Lumumba understood his role as an expression of the popular will, which the co-ops and assemblies would someday represent. At important junctures, he would often say, “The people must decide.”

The mayoral race was a testament to what Lumumba had built in Jackson and elsewhere. Rukia Lumumba gathered support from MXGM supporters across the country. The $334,560 raised in 2013 by Jonathan Lee, the young black businessman Lumumba faced in the runoff vote, was still much more than the $68,753 Lumumba’s campaign raised that same year. Lee, however, was mostly unknown in town, except to his friends on the state’s chamber of commerce. MXGM’s organizing efforts, combined with Lumumba’s long-standing reputation, resulted in a landslide. On May 21, he won 86 percent of the Democratic primary vote, guaranteeing him the mayoralty. The Lumumba campaign’s slogan, “One city, one aim, one destiny”—an homage to an old Garveyite saying—seemed to be coming true.

“The spirit behind Chokwe was high,” said Walter Zinn, a local political consultant. “It was probably the highest it had been in twenty years.”

Not everyone was on board, however. “I remember getting all these calls when he was elected mayor from white business owners—they were terrified,” City Councilman Melvin Priester Jr. told me. “They were afraid that he was going to treat them like they had treated a lot of black people, like a Rhodesia situation.”

Nia and Takuma Umoja are co-founders of the Cooperative Community of New West Jackson. The group has been buying abandoned properties in an eight-block section of its neighborhood and turning them over to a community land trust.

For Lumumba and his new administration—full of MXGM partisans—the first order of business was damage control. The city’s roads and pipes had been allowed to deteriorate to the point of disfunction. An EPA consent decree loomed over the crumbling wastewater system. Funds needed to be raised for repairs; perhaps, afterward, the money could be used to seed cooperative businesses for doing the necessary work. Lumumba used the political capital he’d won in the election to pass, by referendum, a 1 percent sales tax increase. He raised water rates. Practical exigencies won the day.

“We didn’t win power in Jackson,” Akuno said. “We won an election. It’s two different things.”

To pass the 1 percent tax, Lumumba had to accept oversight for the funds from a commission partly controlled by the State Legislature—a concession that not even his more conservative predecessor would accept. He hoped that, later on, he could mobilize people in Jackson to demand full control over their own tax revenues, but the city was in an emergency, so for the moment the commission would have to do.

From his new position, as director of special projects and external funding, Akuno tried to keep the Jackson-Kush Plan on track. However long the administration would last, he wanted to set up structures that would outlive it. He drew up plans for a $15 million development fund for cooperatives, using money from the city, credit unions, and outside donors. He wanted to create worker-owned co-ops for all the city’s needs—for collecting garbage, for growing the food served at schools, for taking on the plentiful engineering challenges. To help, Lumumba called for rules to direct more contracts to local businesses. And there were plans to roll out a participatory budgeting process, based on experiments in Brazil and New York, through which Jacksonians could decide how to allocate public funds directly.

This article appeared in the April issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

Ben Allen, president of the city’s development corporation, started getting to know the new mayor, and he was pleasantly surprised. When he invited Lumumba to a garden party at his country club, the mayor made an appearance. “Our fears were gone,” remembered Allen, who is white. “He wanted to work with us.”

Jackson’s troubles, by 2013, were more than black and white. An investment firm in Santa Monica had bought up more than half of the private buildings downtown. Israelis and Chinese were getting in on the action, too. Far from the RNA’s old secessionist strategy of the 70s, Lumumba was forming coalitions where he could, with whoever would work with him. Co-ops and assemblies took a backseat to balancing the budget, at least as far as official business went.

Two miles from downtown along Capitol Street, however, just blocks from the entrance to the zoo, another germ of the cooperative vision was beginning to sprout. In early 2013, MXGM members Nia and Takuma Umoja moved with their children from Fort Worth, Texas, into a small wooden house next to a local dumping ground. Slowly befriending their new neighbors, they started clearing the garbage away, replaced it with raised soil beds, and declared an eight-block section of the neighborhood the Cooperative Community of New West Jackson. They began putting their neighbors, many of whom grew up as sharecroppers, to work on a construction crew and growing food. Discreetly, the cooperative bought up more and more property within the territory, intending to transfer it to a community land trust. They renovated abandoned houses and painted them with bright colors. It was all part of the plan—the same plan that put their old friend Lumumba into office. And, like the mayor, the Umojas were making new friends as well.

They started building relationships with power brokers in town, including developers, pastors, and politicians—people who had their own plans for sprucing up the area around the zoo. Back in Fort Worth, the Umojas’ community center fell victim to the threat of eminent domain, and they didn’t want to see anything like that happen again. As renewal progressed around them, they would need powerful supporters. But where they saw necessity, Akuno saw an effort to swallow up the movement.

An abandoned house in West Jackson

“Our enemy saw an opportunity,” he said. Both the mayor and MXGM’s flagship cooperative project were teaming up with the likes of Ben Allen. If divide and conquer was the intent, it succeeded; a rift between Akuno and the Umojas deepened until they were acting more like competitors than comrades. According to Allen’s email signature, “Downtown redevelopment is like war.” (Last month, Allen was indicted for embezzlement of his organization’s funds.)

“We knew, when we got here, what we’d have to do to make sure that we’re at the table when decisions about development are being made,” Nia Umoja told me. “Our folks are never at the table.”

The forces that have kept #BlackLivesMatter trending are not exactly what one might expect from the headlines of black men killed by police. In reality, it’s primarily a queer- and women-led movement. It is also only marginally interested in whether cops wear body cameras. Its leaders are not afraid to use the word “capitalism,” and they do so derisively. (That slogan, “Black Lives Matter,” originated with Alicia Garza, an organizer of domestic workers.) They feel that black lives will not matter in this society until it adopts a different system for determining what and who matters. In this movement, as in so many movements before, only a tiny sliver of its variform lifeblood gets into the news.

The civil rights struggle of the 1960s was no exception, for it was never about civil rights alone. Malcolm X preferred to speak of “human rights,” and it was in those terms that he wanted to bring a case against the US before the United Nations. Martin Luther King Jr. marched for “justice and jobs”; he died supporting sanitation workers. “Black power,” “black liberation,” “black lives”—these betray demands more comprehensive than either headlines or mythic hindsight allow. And they were never far from economics.

Cooperatives have a long history in black American life. There were co-ops for sharecroppers seeking better markets for their produce, co-ops for townspeople who wanted better prices for basic commodities, and cooperative communes that tried to create a new world apart from white supremacy.

Twenty years ago, Jessica Gordon Nembhard, a political economist at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, began to notice a hidden economy at work in African American life. Again and again, people were organizing themselves in creative forms of cooperative enterprise, democratically owned and managed by those who took part. Starting with the co-ops listed in W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1907 book Economic Cooperation Among Negro Americans, she began reconstructing a history, eventually published in her 2014 book Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, that, before, had only been told in bits and pieces, passed down through families but rarely seen as significant. There were co-ops for sharecroppers seeking better markets for their produce, co-ops for townspeople who wanted better prices for basic commodities, and cooperative communes that tried to create a new world apart from white supremacy. Where white banks wouldn’t lend money, credit unions arose. These efforts faced sabotage and repression. But they were always around. “There’s really no time in US history when African Americans were not doing cooperative projects,” Nembhard told me.

In the mid 1960s, Black Power first became a force among a group of landowners and co-op members in Lowndes County, Alabama, before expanding to the country’s urban centers. “The Black Power concept came into being because of those farmers who were independent in and of themselves and understood the value of collective organizing and collective ownership,” Wendell Paris, a civil rights activist and cooperative developer in Alabama and Mississippi at the time, told me. In cities, the movement took the form of the Black Panthers’ rifle-toting demonstrations, along with their food, housing, and health programs.

For years, Paris traveled around the South helping black farmers hold on to their land and build wealth cooperatively. Black farmers in Louisiana weren’t getting paid fairly for their sweet potatoes, so they started a sweet potato cooperative and found their own markets—in many cases up north. In Alabama, farmers who were getting a raw deal on fertilizer formed a co-op to buy it in bulk from elsewhere. Paris assisted in forming the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in 1967. Black activists during that period visited co-ops in Africa and Israel. After years of agitating for voting rights, Fannie Lou Hamer organized the Freedom Farm, a cooperative meant to secure the gains of civil rights with—to use the now-fashionable term—food sovereignty. Today, this tradition is in a period of renaissance.

“Since the Great Recession, there has been a huge amount of interest,” Nembhard told me. “Everybody’s figuring out that there’s not a lot for them in the main economy and that they need to find some viable alternatives.” Cooperatives, she has found, can thrive at the economy’s margins, at the sites of market failure and exclusion. Their participant-ownership structure keeps wealth in local communities and acts as a bulwark against financial crises. “Co-ops can address almost every economic challenge we have,” Nembhard said.

Elandria Williams is an organizer at the Highlander Center in Tennessee, a historic base camp for agitators and activists. (A photo of King at Highlander, with a caption describing it as a “Communist Training School,” became a notorious piece of anti-civil rights propaganda.) Williams studies examples like the Emilia-Romagna region in Italy, where co-ops enjoy tax benefits and have flourished in sectors from agriculture and handicrafts to high-tech industry. Cooperatives don’t just happen one business at a time; they require an infrastructure to thrive, an ecosystem. That’s why she has been working to create the Southern Reparations Loan Fund, an investment vehicle for the new generation of co-ops.

“We’re trying to figure out what an economy would look like, not just what enterprises look like,” Williams told me. That’s part of why Lumumba’s election mattered so much.

“When we thought we had the mayor in Jackson, and that we were going to have a real example of a black municipality that was embracing the totality of a cooperative commonwealth, we were really excited,” Nembhard told me. It encouraged black-led co-ops around the country.

For instance, followers of the late James and Grace Lee Boggs have been planting a network of cooperative enterprises on the abandoned lots of Detroit. In New York, the city government is investing $3.3 million in creating new worker cooperatives alongside the existing ones in industries like home care and catering. A cooperative security company has started in a Queens housing project. Charles and Inez Barron, longtime movement friends of Lumumba’s, want to use their positions in the state assembly and the city council in New York State to set up co-ops in some of New York City’s poorest neighborhoods.

Cooperatives take time, and this new economy is coming along too slowly for those who need it most. The generation of farmers that organized under the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in the 1960s and 70s is aging out of existence, and the new generation of black co-ops is still emerging. The story of black cooperatives, as much as it is one of “collective courage,” in Nembhard’s words, is a story of loss. The loss once came in the form of Governor George Wallace’s Alabama state troopers pulling over a truck full of cucumbers until they turned to mush in the summer sun; then it was a police raid with a tank; then an aortic aneurysm.

The Pink Potato Cookhouse has been rehabilitated to serve as a community kitchen.

When Chokwe Antar first looked at his father’s body in the hospital room, he made the decision to finish what had been begun. He didn’t say anything; there still had to be discussions in MXGM about the next move. His wife was pregnant. Some still felt he wasn’t experienced enough, but ultimately, the movement’s decision echoed his own, and he ran on a promise to continue what his father had started. Throughout the country, MXGM members mobilized again. But by the time of Lumumba’s death, the Jackson-Kush Plan was secret no more, and the city’s business class was better prepared to oppose it.

Socrates Garrett is Jackson’s most prominent black entrepreneur. He went into business for himself in 1980, selling cleaning products to the government; now, he and his nearly 100 employees specialize in heavy-duty environmental services. The story of his success is one of breaking through Mississippi’s white old-boy network, and to do that his politics have become mainly reducible to his business interests. He is a former chairman of the chamber of commerce and serves on the boards of charities. He’s a self-described progressive who supported the last Republican governor, Haley Barbour. He became a political force—by necessity, and with less ideological freight than the partisans of MXGM.

“I had to have relationships with politicians,” Garrett told me. “If you’re not doing business with the government, you’re not in mainstream America.”

Garrett became a Lumumba supporter when it became clear who was going to win the election, but he grew disillusioned quickly. The MXGM-led administration didn’t play his kind of politics. “They started putting people in from different walks of life,” he recalled. “They had a lot of funny names, like Muslim names.” He was informed that he should not expect special treatment. Safiya Omari, Lumumba’s chief of staff, insisted that he was being treated like any other contractor, but Garrett perceived it as a snub—right when the militant black mayor seemed to be bending over backward to assuage the White Establishment.

Nia Umoja pushes a piece of plywood against a doorway on an abandoned house acquired by the Cooperative Community of West Jackson, which plans to restore the building to function as a center for folk art.

“Here you are, a black man—you start from scratch and work your way up, thirty years out here struggling—and there’s something wrong with my business model?” he said.

Garrett couldn’t wrap his head around how cooperatives were going to take on big city contracts, with all the bonding and hardware such work requires. Mississippi law doesn’t even have a provision for worker or consumer cooperatives; those that do exist must incorporate out of state. “In my opinion, it was going to produce chaos,” he said. He set about looking for a new mayor to raise up, and before long came upon Tony Yarber, a young bow-tied black pastor and city council member from a poor neighborhood. (Yarber’s LinkedIn profile still lists his profession as a motivational speaker.) What he lacked in age and experience was more than made up for in his willingness to collaborate.

Garrett and Yarber quietly set out to organize a run against Lumumba in 2017, but when the mayor died, their chance came sooner than expected. The white business class that had tolerated and even liked Mayor Lumumba wasn’t ready to risk his young and little-known son. Jackson Jambalaya, a straight-talking conservative blog, ridiculed him as “Octavian.” Chokwe Antar’s posters, between plentiful exclamation points, made promises of “continuing the vision”; Yarber, for his part, told the Jackson Free Press, “I don’t make promises to people other than to provide good government.” Garrett was his top individual donor.

The result was a reversal from the election a year earlier. Jackson’s population is 80 percent black, and Chokwe Antar won a solid majority of the vote in black neighborhoods. But the white minority turned out in droves, urged by last-minute canvassing in more affluent areas, which voted 90 percent for Yarber. Narrowly, on April 22, Yarber won.

Yarber removed almost all the members of the previous administration. Even Wendell Paris, who’d been working part time to develop community gardens on city land since before Lumumba’s administration, was dismissed. When I visited city hall a year later, Yarber’s sister, a police officer, was sitting by the metal detector at the entrance, pecking on the same iPhone that was once issued to Lumumba.

“The whole sense that we’re going to do something great has sort of dissipated,” Safiya Omari told me.

Sitting on his front porch, wearing a faded T-shirt from the first mayoral campaign and a black cap with Che Guevara inside a small red star, Akuno tried to explain to me the experience as he slathered his two small children in natural bug repellent. With the 1 percent tax and the water-rate hikes, they’d alienated part of their base. But capitalism didn’t leave them a choice. He was following the news of Syriza, the leftist party in Greece, as it tangoed with the Troika. “I feel like I know exactly the conversations they are having behind the scenes,” he said. “I’ve been there.”

Across town, Garrett was feeling blessed. Mayor Yarber put things back to what he was used to. “Every time, God sends an answer,” he told me. “But I can assure you that that movement is alive and well. And I can assure you that unless Yarber is razor sharp, they’ll be back.”

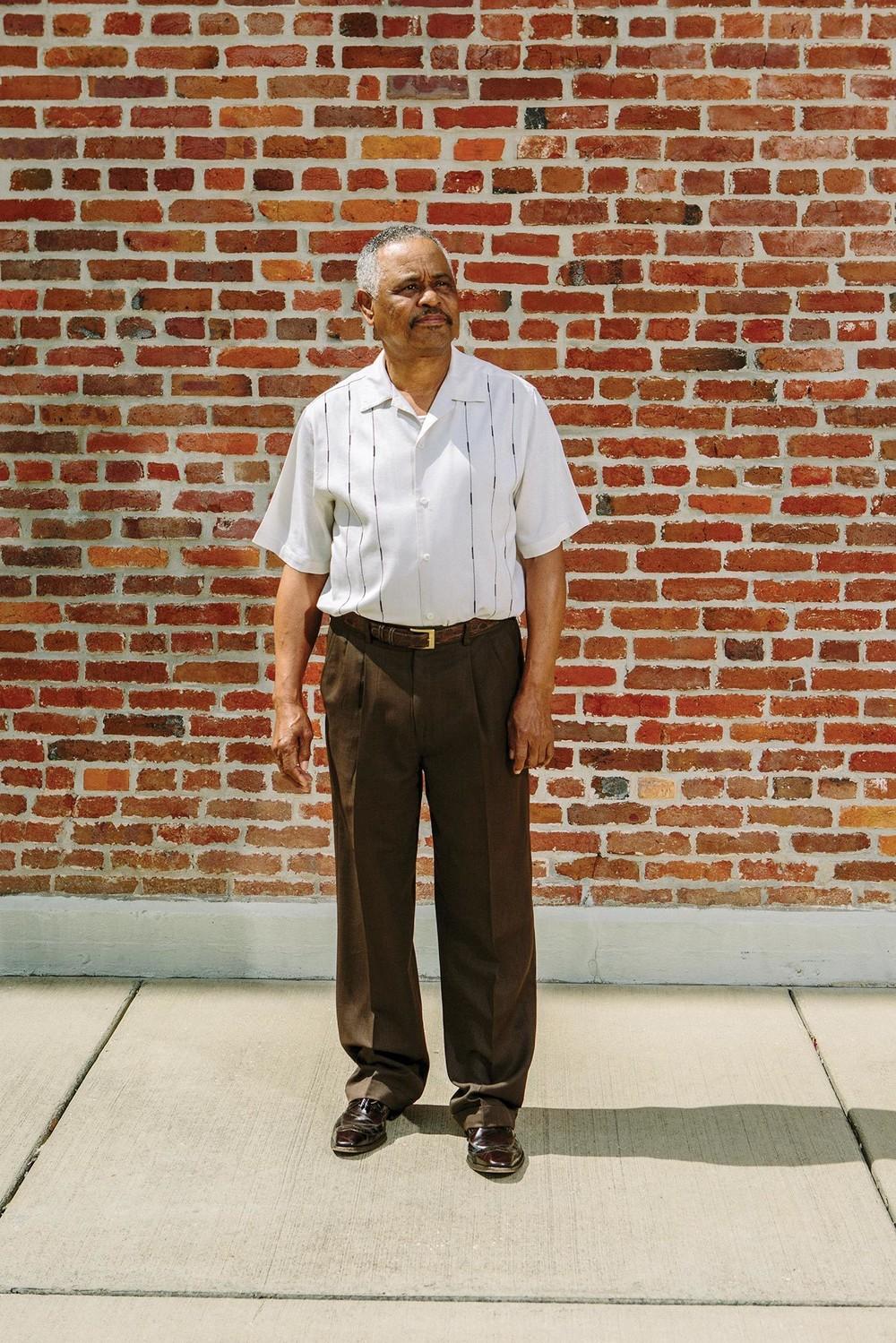

Socrates Garrett, Jackson’s most prominent black entrepreneur, objected to the way the Lumumba administration did business.

In May 2014, just months after Lumumba’s death, hundreds of people came to the Jackson State University campus from around the country and the world for a conference called Jackson Rising. They learned the history of black-led cooperatives from Nembhard and took stock of what might have been in Jackson—and what might be. Lumumba’s image appeared on the cover of the program, and on the first page, he spoke from the grave with a signed-and-sealed resolution from the mayor’s desk. “Our city is enthused about the Jackson Rising Conference and the prospects of cooperative development,” it said, as if nothing had changed. In fact, city hall’s expected support for the event lasted no longer than Lumumba’s tenure.

MXGM was meanwhile hatching a new organization, Cooperation Jackson, to carry on the work that had been started. Akuno enumerated a four-part agenda: a co-op incubator, an education center, a financial institution, and an association of cooperatives. Plans were soon underway to seed, first, three interlocking co-ops: an urban farm, a catering company named in honor of Lumumba’s wife, Nubia, who died in 2003, and a composting company to recycle the caterers’ waste back into the farm. Akuno raised money from foundations, entertainers, and small donors, and the Southern Reparations Loan Fund would be pitching in as well. Cooperation Jackson started buying up land for its own community land trust. Its members restored and painted what would become the Lumumba Center.

Jackson’s hot summer seemed especially apocalyptic last year. In South Carolina, Dylann Roof had murdered nine African American worshipers in a Charleston church; day after day, there was news of black churches across the South burning. Calls were mounting to take down the Confederate battle flag flying over the South Carolina Capitol, but comparatively few were talking about the stars and bars that still cover a substantial portion of the Mississippi state flag everywhere it appears. The Supreme Court declared same-sex marriage the law of the land, overturning the Mississippi Constitution’s marriage amendment, and the preachers who heavily populate the radio spectrum in Jackson declared the United States of America definitively captive in the talons of the devil. In the Lumumba Center’s backyard, Cooperation Jackson’s Freedom Farm consisted of a few rows of tilled earth, and in the kitchen, Nubia’s Cafe was having its first test run. Akuno and others were planning a trip to Paris for the UN climate summit. Down the road at the Cooperative Community of New West Jackson, Nia Umoja and her neighbors had bought 56 properties for their land trust. “We’ve taken almost all the abandoned property off the speculative market,” Umoja said.

Socrates Garrett was Jackson’s most successful black entrepreneur when Lumumba became mayor. “Here you are, a black man—you start from scratch and work your way up, thirty years out here struggling—and there’s something wrong with my business model?” he said.

In the wake of Roof’s shooting spree, Chokwe Antar helped organize a rally at the state capitol to demand changing Mississippi’s flag, alongside local politicians, activists, and hopefuls. The actress Aunjaune Ellis, flanked on either side by guards in black MXGM T-shirts, called for “rebranding our state” and “a different way of doing business.” Chokwe Antar led a chant: “Stand up, take it down!” “Free the land!” followed. Then, of course, “By any means necessary.”

Chokwe Antar’s name was in the national news a week later. In Clarke County, a police officer stopped Jonathan Sanders, a black man with a horse-drawn buggy, and he wound up dead after the cop put him in a chokehold. Chokwe Antar took the case. The incident became a possible flash point for the Black Lives Matter movement’s roving attention, but the story soon faded, and in January, a grand jury declined to indict the officer. The rebel flag still flies over Mississippi. The state, also, has been vying to wrest control over Jackson’s valuable airport—another blow to self-rule for the black-majority city. And the decision has been made: Antar will run for the mayor’s office again in 2017.

The flag campaign was the subject of conversation over grilling vegetables and chicken for dinner at the Lumumba Center in late June. Akuno, pacing back and forth over the grill, led the discussion. “I think with some of this Confederate stuff—that’s a distraction,” he said. “Is that really our agenda? Did we define it, or did the media define it, saying that this is within the limits?” He’d been saying as much to Chokwe Antar. Akuno wanted to keep the focus on the co-ops and the assemblies and elections—real counter power, backed by self-sufficiency.

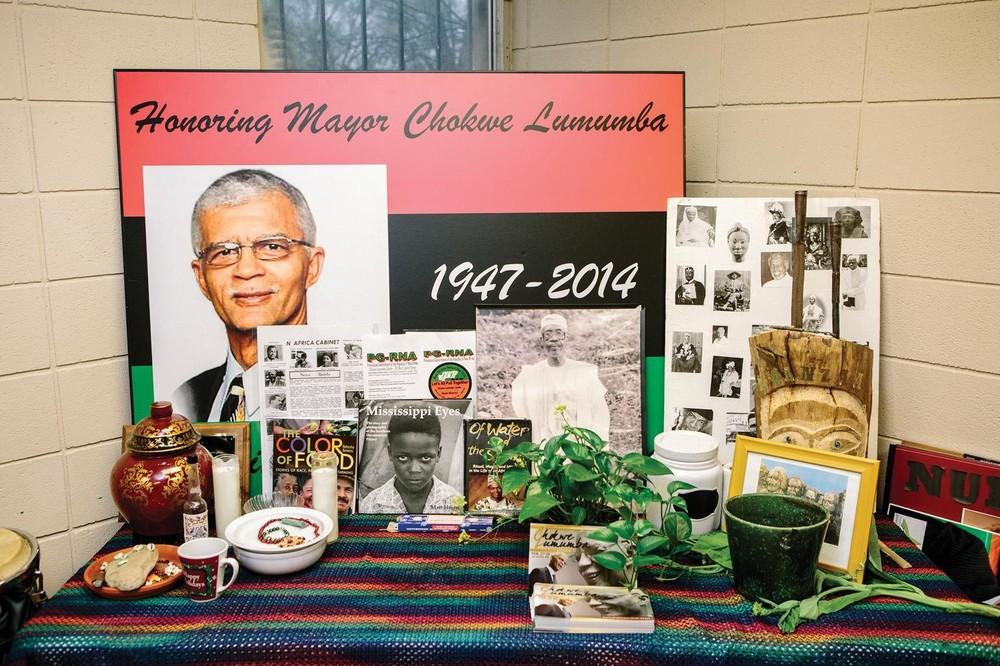

An altar to Chokwe Lumumba inside the Lumumba Center

“Nothing don’t change, whether the flag comes down or not,” said New Orleans housing activist Stephanie Mingo, from the other side of a picnic table. “There’s still going to be red, white, and blue.”

“I’m not a fan of the Black Lives Matter thing—because, to be honest with you, they don’t,” Akuno went on. “Your life did matter, when you were valuable property. You were very valuable at one point in time. We’re not valuable property anymore.” His pacing took him and his gaze back to the grill, where he flipped over a hunk of chicken.

“My argument is to tell other black folk, let’s start with the reality.”

This article appeared in the April issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

Note: Wording in this story has been updated to more accurately reflect the relationship between the Cooperative Community of New West Jackson and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement.