Michael Christopher Brown’s new book, Libyan Sugar, is about the Libyan revolution. Then again, in many ways, it’s not. It’s about being a photographer and bearing witness to life-changing events. It’s about family and the lengths people go to in order to test themselves.

Alongside his stunning, often harrowing photos of the years of upheaval and violence that wracked Libya, Brown includes text messages and emails from family imploring him to return, forwarding news bulletins, asking after him. The juxtaposition of his intimate, diarized personal life with the images of extreme violence on a geopolitical scale is both unsettling and thought-provoking.

Videos by VICE

An integral part of the book is the bombing in which Brown was injured, and photojournalists Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros were killed. We caught up with Brown to talk about the project.

WARNING: This post contains graphic images.

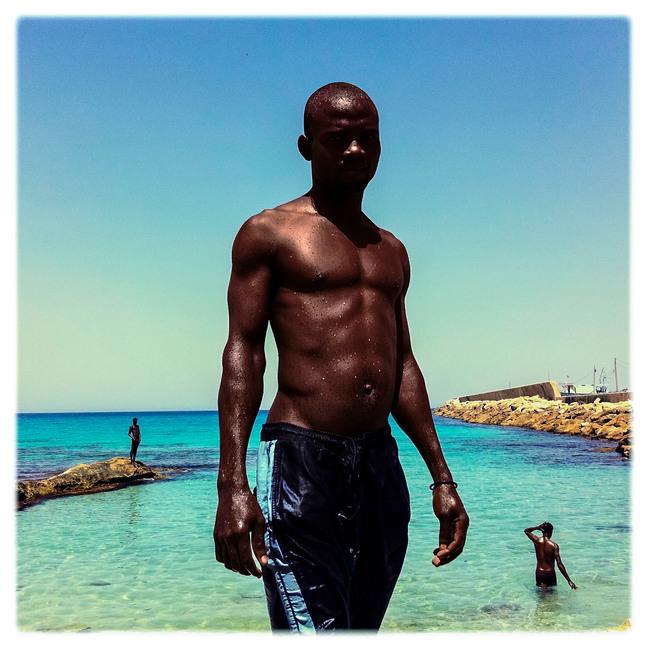

As Tripoli fell, thousands of Sub-Saharans took refuge in a fishing harbor as revolutionaries were rounding up Sub-Saharans, largely on the assumption they were Gaddafi supporters or mercenaries. Many if not most of these Sub-Saharans planned to escape to Europe by boat. Janzour, Tripoli, August 31, 2011. 13:18:46.

VICE: In a previous interview with VICE you said that honesty in photography can be a product of being pushed beyond one’s limit. Was your work in Libya, and your decision to return after numerous injuries, part of an effort to push yourself beyond your limits? And did that take your work to a level where it was fundamentally different from what it would have been were you working on less demanding terms?

Michael Christopher Brown: Yes and yes. Libya was the place where I came to that realization you mention. After being injured a second time, life became less about photography and more about understanding a voice. I made the book for myself, so there was also a need to be transparent, for better or worse, as with a diary. Hence the inner dialogue and the inclusion of communications with family and friends. I felt the book would also be more useful to others that way, rather than just showing people a pile of war pictures.

You talk in the book about feeling tied to those people you spent time with. A sort of guilt about your ability to leave while the subjects of your work could not. How big a factor was that in keeping you there working?

It was a factor, but I stayed in Libya for a number of reasons. I did have compassion for the Libyan situation. There was a feeling that their war was also ours, or mine, because it was—at least at the time—considered a fight for dignity and human rights. I identified with these values, and eventually the place and people became a part of me in some way.

Revolutionaries at a hospital. Ras Lanuf, March 27, 2011. 13:33:08.

What’s your view on impartiality in photojournalism? I’ve heard wildly varying views on this from different photographers. Some find the idea of objectivity in such situations laughable. Was objectivity something you sought, or was that simply beside the point for you?

I just always do what works for me, using my own values and experience. Objectivity, subjectivity, these are just words we use to describe a process where we take a certain approach—but I wasn’t interested in being in control of a process while in Libya. It seemed more like an opportunity to grow, a more creative process that in order to be useful could not be controlled. I was curious about everything. I was following my nose. This is also partly why I used a phone to take pictures and jumped in trucks evacuating soldiers from the frontline and so on. I wanted to remove myself from the process of photography, of its control and its history. I used the same tool Libyans used to begin, sustain, and further their revolution: a mobile phone. In that sense I was taken out of my role as a photographer and became more of an observer.

The inclusion of texts and emails from your family was a surprise to me. The concern shown in them is moving in itself—but alongside images of brutal violence they become even more sobering. Was involving your family in the work a difficult decision for you?

No, it wasn’t. I sought permission from family and friends. Their involvement was necessary because the book is not just about going to war; it is about going home. The idea was to be open about the experience in order to best preserve it for myself, as well as to create a character that could be identified with by others. A small percentage of people have been to war or can identify with the experience, but everyone does—more or less—have friends and family and can understand love. And perhaps they know loved ones who have been, or are in, war. In the texts, then, are paths into the photographs. Ultimately, what I discovered while pulling away from my family, my girlfriend, close friends, was that my life was less about some quest or war, however necessary it may have been or have seemed at the time, than it was about love. But I needed to go through the process in order to understand that.

Remains of a body. Abu Salim hospital, Tripoli, August 28, 2011. 12:56:48.

There are a lot of very graphic images in Libyan Sugar. It’s something people at times moralize over in reporting. How would you describe your views on depicting the dead, or very graphic injuries? What role do these images play for you in the context of the wider project?

Images depicting the dead—very graphic images—these are images of war and they are essential. War is also surreal and at times incredibly beautiful. Those sorts of images are also in the book. The real extremes of human emotion, as a society is turned on its head, when people are tested, these are emotions that can only be experienced in war and they lie between life and death. So at opposite ends of this spectrum we have beautiful moments contrasted with horrific moments. That’s one reason why I aligned texts from my mother with images of brutality. I included a number of these images. I saw many bodies, hundreds of them throughout the year. The images we see in many publications—say of men on patrol or bombs exploding—that’s not war. That is something else—advertising, perhaps. We don’t see true war pictures often because they do not inspire war; they inspire mass numbers of citizens to stop wars.

How did the bombing that killed Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, and injured you, change they way you see yourself and the work you did in Libya?

There is a lot I could say about this, and I talk about it in detail in the book. In immediate terms it made me step back and analyze what I was doing with my life. For several months after I didn’t really do anything, nor did I have the energy to.

That day we had spent hours moving in and out of a building on Tripoli Street. There were snipers nearby, and rebel fighters trying to smoke them out with burning tires. It was very intense. We went back to our safe house to get more film and recharge batteries at one point, and some of of us were initially inclined to stay, though Tim was ready to head right back out. In the end, my not wanting to miss anything led to me wanting to go back out with Tim in spite of my misgivings. I wasn’t listening to myself, and because of that I wound up back on that street that afternoon when the bombing happened. After that, my sense of self-criticism became sharp. I had some guilt for a while, but overall I’m a more intuitive individual today, largely due to that. I don’t always make the right choices, but as a result of those events I am closer to my gut and better understand the reasons why I have certain motivations. These thoughts are in the book and in the video installations that I hope to show later this year.

How useful to you was it to make this book? A reader might feel that composing this piece of work has put parts of your experience into context and given it all some sense of meaning.

Making the book was a cathartic experience. It took several years and various iterations, and that it exists now on my desk is a bit surreal. It has also helped to release some weight I’ve carried around since, as now that experience exists in a physical space outside myself.

See more images from Libyan Sugar below:

Unguarded weapons depot. Between Sirte and Waddan, October 26, 2011. 15:21:06.

A rally in Benghazi on April 8, 2011. 18:34:41.

Unidentified. Hikma hospital, Misrata, Apri 18, 2011. 12:03:04.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE