This article originally appeared on Noisey UK.

I remember being 15, blasting out music from my bedroom, and my Dad bursting in. “What’s that noise?!”, he yelled in his disgruntled Northern Irish gruff. “It’s just noise! It sounds like a dying horse!” He turned and slammed the door behind him.

Videos by VICE

The track I was playing was Public Enemy’s “Rebel Without a Pause” and, to be fair to him, it was a hell of a lot of horse-death to be dealing with at 10 AM. But that’s what hip-hop was to me then. The mainstream portrayal of the genre has always been aesthetically—and sonically—as slick, crisp and clean as a freshly razored fade. But at the fringes of that image exists a broad band of tangled noise: a hectic beat-driven assault, a cascade of glitches, an industrial eruption of sound.

The path we frequently tread through hip-hop history is as follows: the genre originated in the Bronx in the late 60s and 70s as a cultural movement, originally characterized by its four elements (DJing, b-boying, graffiti, and rapping). Its Golden Era took place in the late 80s, and artists like Rakim, A Tribe Called Quest, and Wu-Tang Clan all became touchstones for the sounds we hear today. But while Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash were laying the foundation for quintessential hip-hop, another strand that’s an equally important component in the genre’s history—a sound known as noise-hop—was just beginning.

Just as the genre of rock extends towards an extreme and becomes noise-rock, modern hip-hop, at its edges, becomes noise-hop, with artists like B L A C K I E, clipping., and El-P just a few that have contributed towards creating a much more unique and expansive sound, that takes cues from punk, metal, industrial, the LA noise scene, and the early sonic chaos from which hip-hop was born. When we talk about noise-hop we aren’t talking about your average boom-bap, finger-snap rap; noise hop is the sound of belligerent beats fighting with harsh digital-distortion and fucked up samples.

Artists like Death Grips, albums like Yeezus—they’re all current, modern examples of noise-hop. But behind those two well known reference points, there’s an entire history to the genre that’s been largely overlooked and written off as background noise. I guess it’s best if we start at the beginning.

Continues below

THE BIRTH OF NOISE-HOP (1980-85)

It was around 1980 when Bristol post-punk band The Pop Group were touring in New York, proving their worth as No Wave pioneers. The group’s frontman Mark Stewart tuned into Kiss FM (yes, even white kids from Bristol were well up on their hip-hop back then), and the DJ at the time, Red Alert, was on the ones and twos, injecting the airwaves with some sonic madness. The story goes that no less than an hour after tuning into that radio station, Stewart passed a construction site and became enthused by the sound of a piledriver slamming into the ground. The industrial city, DJ Red Alert’s chaotic scratching, the distorted echo chamber effects of Afrika Bambaataa’s recently released Death Mix, the booming bass of dub sound systems—they would eventually pile together into a new, as yet unfounded, salmagundi of sound in his head.

A few years later, in 1985, these influences become the sound of Stewart’s second solo album, As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade, a landmark record for what would initially be referred to as “industrial hip-hop”. The beginnings of noise-hop were formed in a confluence of these outsider industrial experiments. But it was once they were mixed with insider innovations from the likes of Hank Shocklee—member of Public Enemy’s production team, The Bomb Squad—that they really began to shake the foundations of hip-hop.

BLACK SKINHEADS

The Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade was equitable to a war report, and in keeping with that militant tone—Public Enemy (who claimed hip-hop was the “Black CNN”)—were truly sonic rebels. The rap group would take hip-hop to new heights with their music concrète of densely layered funk, righteous political mandate and energizing breakbeats, going on to inspire noise in other genres, from Rage Against The Machine to The Prodigy.

“I wanted to do something that was not melodic…” Public Enemy producer Hank Shocklee said in an interview with The Quietus earlier this year. “Frequencies that clashed with each other and created another frequency of dissonance… the feeling of rock and roll without a guitar.” It’s the same old punk philosophy we know as making something out of nothing.

“That whole cutting and pasting, smash ‘n grab… that was punk!” asserts Mark Stewart, as he remembers seeing what he described as the “oiks” and the original “black skinheads” slamming against the walls to the music. Coincidence or not, it’s worth noting that Stewart used the term ‘black skinhead’ about 30 years before Kanye West. Was this punk for kids in black skin?

Not only do the genres clearly share the same spirit, noise-hop has often drawn upon the distortion, nihilism, speed and abrasion of hardcore punk to make its noise heard, from Public Enemy sampling Slayer’s thrashing guitars in “She Watch Channel Zero!” (below) or Death Grips utilising the descending chugs of Black Flag’s “Rise Above” on their track “Klink”.

THE IMPACT OF SAMPLING AND PRODUCTION

Of course, the art of sampling as a part of hip-hop culture is vital—everyone from Dr. Dre to Atari Teenage Riot have utilized the MPC sampler to bring records from the past into the present. With sampling, anything goes. Any genre; any sound. And it’s this boundless eclecticism that would define the shape of noise to come. In order to evade perpetual copyright lawsuits, producers like DJ Premier and J Dilla would take smaller samples of records (rather than loops) and tap them out on the MPC or keyboard, allowing for a choppier rhythm and messier sound.

It’s this technological adaptation—using small samples of records, rather than loops—as a response to legal oppression that propelled hip-hop’s voyage into indiscernible noise. The greatest cyber-punk pirate of this sound is, without a doubt, producer El-P (formerly of Company Flow, co-founder of Definitive Jux records and now Run The Jewels). “Growing up being an admirer of graffiti… it wasn’t about the safety or the guarantee of anything, it was about the risk… it was about style… it wasn’t about sounding like anything that was already proven,” explained El-P in his Red Bull Music Academy lecture.

El-P came through the New York underground hip-hop scene in the 1990s, and from the off was canonized for being “independent as fuck.” His first group Company Flow (founded in 1992) may have kicked the ball into play left of field, in the face of the dominant shiny-suited ‘Jiggy era’, but it wasn’t until his work on Cannibal Ox’s debut The Cold Vein, in 2001, and his own debut solo record Fantastic Damage, in 2002, that we saw the real noise-rebel we’ve come to know as El-P.

Inspired by reading Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (later adapted for the film Blade Runner) and a love for the cold hard punchy old school beats of Boogie Down Productions, Schooly D and The Beastie Boys, El-P got to work, armed with not much more than a turntable and an EPS keyboard sampler (also used by RZA on early Wu-Tang records). El-P’s production on The Cold Vein painted a picture of a dystopian present in New York City, while Fantastic Damage explored personal issues of lost love, domestic violence, and paranoia. Those two records are as sonically disorientating as they are emotionally turbulent.

Despite possibly wanting to distance himself in more recent years from the backpack rocking overzealous indie nerds that crowded around his record label, what El-P did was to help shine a light on abstract and independent hip-hop. He opened a pandora’s box of weirdos, meaning mind-altering groups like Dälek could start to make total sense in this new landscape.

Dälek’s 2002 debut full-length From the Filthy Tongue of Gods and Griots cemented them as the torch bearers of noise-hop, blending dissonant drones and ethereal screeches with heavy industrial drums. They took the nauseating post-rock of My Bloody Valentine and used it to paint another dystopian post-apocalyptic vision. It was from here that horrorcore, hardcore, and experimental hip-hop witnessed a resurrection in the smouldering embers of the post-9/11 nightmare. Dälek’s “Black Smoke Rises” (below) encapsulated the sheer horror and confusion experienced around that strange time.

The reaction to war on a global scale twinned with imminent suffering in their own back-yard may have prompted a cognitive dissonance of sorts that matched the dissonance on record. At this time there appeared to be an emergent schism in underground hip-hop’s consciousness, represented through the lyrical nihilism of horrorcore in opposition to the politically analytical/self-reflecting noise of artists like Saul Williams—in collaboration with Trent Reznor as Niggy Tardust (2007), Dälek, and El-P (as well as what could’ve been Zack De La Rocha’s lost solo debut following the breakup of Rage Against the Machine in 2000, which was rumoured to feature production by both El-P and DJ Shadow).

So in the space of two decades noise-hop had experimented, developed and morphed in many different ways, but it was perhaps still too divergent to be move beyond its novelty and obscurity to become a significant movement. By the late noughties (2006-08) mainstream hip-hop was seeing the return of Jay-Z, Kanye was on that 808s and Heartbreak vibe and Lil’ Wayne was… well, Lil’ Wayne. It didn’t seem like the underdog story of noise-hop was going to make much of an impact until the turn of the next decade.

NEW NOISE

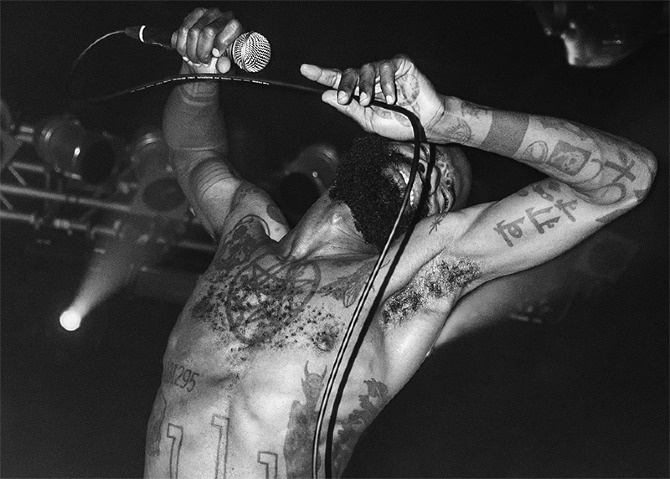

Death Grips, shot by Paul Sethi

Which brings us to the current day. Since their 2010 debut mixtape Exmilitary, Death Grips have been a gateway band for many (including myself) in discovering noise-hop. They cleared the lane for a whole generation of diverse noise-hop artists to make waves. The brilliant and formidable Moodie Black have clearly honoured and developed the lineage of Dälek, while one man band NAH is currently breaking barriers, dually summoning the spirit animals of both Zach Hill and MC Ride into one gnarly hybrid. Earl Sweatshirt has taken a more transcendental approach to noise with his track “Grief” from his album I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside (2015). The song is based around a digitally slowed down sample of Erykah Badu’s “Fall In Love” and as a result it is full of digital artefacts and glitches that turn it into a doomy bellowing heap of noise. It’s perhaps a slightly more nuanced approach than Tyler, the Creator’s explosive contribution to the noise lineage, through his track “Cherry Bomb” (the inspiration for which came after he was listening to Death Grips on his car stereo).

Tri-Angle records have consistently pumped out freakishly noisy beats, most recently in the form of Reducer by North Carolina based producer Hanz. “What I make is definitely influenced by more old school hip-hop, I’m using those sampling techniques to make music that isn’t exactly hip-hop. I’m into the ‘wall of sound’ and a certain density in the music. I think what I’m doing is a continuation of those old techniques/ textures – I’m just more into using that to create disorientation,” Hanz told Noisey over email.

His melee of choppy punk, dub, footwork tempo rhythms and nightmarish soundscapes is befittingly complemented by erstwhile label-mate Evian Christ’s uncompromising Waterfall EP in 2014. Not only did Evian Christ manage to bag a production credit the previous year on Kanye West’s Yeezus (arguably noise-hop’s mainstream crossover record—and a defining noise-hop/pop moment), around the same time he created an obscure conceptual noise album in the form of Duga-3, based on the rather noisy percussive woodpecker-like radio sounds heard on the soviet radar system of the same name—suggesting his production tendencies lean towards (yep, you’ve guessed it) noise.

The most notable new example though, has to be LA trio clipping., who not only push digital signals past their capabilities, distorting their representation, but also use obscure organic samples of household noise (water, glass, alarm clocks, etc.), delivered with such clinical rhythmic precision that it could sit quite comfortably on the radio next to any mainstream g-funk or trap record.

Prior to the release of their debut mixtape Midcity in 2013, William Hutson, clipping.’s primary noise-monger, spent years performing in LA’s noise-scene at clubs like Il Corral (which hosted artists like HEALTH, Wolf Eyes, and Circuit Wound). Speaking with The muSICKLA, Hutson stated that “one of the most incredible things about noise is that people come to it from a whole bunch of different trajectories… If you’re into almost any kind of music, and have an insatiable curiosity to reach for the weirdest, most out-there expressions of that genre, it approaches noise.” With clipping. it’s suggested that digital distortion can be a way of showing the listener the limits of the technology we use to both produce and consume music, kind of like throwing bricks at the force field to show its weaknesses. A belligerent use of music as a form of revolutionary and emancipatory communication that can also get shit well and truly lit in the club.

NOISE GOES POP

When Yeezus dropped it woke everyone the fuck up by saying “Yo Hip-Hop! It doesn’t have to be straight boom-bap you know?! Let’s just dirty this synth line up, drop the beat for a second in exchange for this obscure Hungarian sample that’s in a completely different key to the rest of the song and let’s scream and breathe really heavily over the track like the absolute life-botters we are!” And d’you know what? It totally worked.

It probably needed someone like Kanye West, a producer/rapper of his stature, drunk on enough self-belief to not give two shits about what people thought to forcefully bring the noise-hop to the pop forum. For decades now hip-hop’s influence on mainstream pop has been insidious, all the way from Madonna to N*Sync to Miley, and what Yeezus did was re-configure that hip-hop gene with the mutant noise of forebears like El-P, Shocklee, and even Death Grips. The sound of the underground has been appropriated, even El-P himself has somewhat attenuated his own noise in the form of Run The Jewels, which may not sound as alien as debut Fantastic Damage but is still clearly evolved from those same lets-fuck-your-speakers-up principles.

Without noise-hop we probaly wouldn’t have had artists like Sleigh Bells or FKA Twigs, and it’s even arguable that the noise-hop collage of Public Enemy paved the way for The Prodigy, which in turn influenced reams of harder electronic byproducts.

Why has pop accepted this noise? Was it simply a case of “Yeezy taught me”? Can we claim it back for the underground by making it more harsh and brutal than the radio can handle? It’s up to the new beat architects to decide the shape of noise-hop to come. At least now we see the path we came from in order to help guide us towards the future.

You can find Marcus on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic/Getty Images -

Derek White/Getty Images for STARZ -

Andreas Rentz/TAS24/Getty Images/TAS Rights Management