Photos by Lauren Poor

This article appears in the September Issue of VICE

Videos by VICE

On a windy evening in June, families of the graduating class of Henry M. Gunn High School, in Palo Alto, California, trickled onto the turf football field for the annual commencement ceremony. Below the stage were more than 400 graduating seniors, donning black caps and gowns. Breaking from long-standing tradition, instead of indicating their college names or logos, students festooned their caps with phrases like BLACK LIVES MATTER, 9 TRUANCY LETTERS LATER, and I AM A LEAF ON THE WIND. WATCH HOW I SOAR. A few months earlier, principal Denise Herrmann had proposed a ban on adorning caps, but she allowed students to add non-collegiate decorations after they protested. Her rationale was that having college names on graduation caps suggests that the ultimate purpose of high school is to get admitted to a top college or university, and that there is only one path to success, an entrenched belief in Palo Alto that the administration has been recently trying to dispel.

Among the three student speakers at the ceremony was Allyna Moto-Melville, whose great-grandfather was the school’s founder, Henry M. Gunn. “Even through the vicissitudes of high school, the friend drama, the C’s and D’s on math tests, the external and internal pressure to go to a top school, we, the Class of 2015, have that love and curiosity and strength in ourselves that Dr. Gunn dreamed of,” she said from the podium. “We are resilient, courageous, and compassionate. We have gone through trials and tribulations that no high schoolers should ever have to go through, and yet we have come out of the battle stronger than before.” Though she didn’t say it explicitly, everyone in the audience knew what she was referencing: Starting last October, three students and one recent graduate from Gunn and Palo Alto (Paly) high schools had taken their own lives. And it wasn’t the first encounter the town had had with youth suicide. Between 2009 and 2010, at least five Gunn students or recent graduates committed suicide. Then, in January 2011, a Paly senior killed herself.

In response to the most recent tragedies, the national media and school administration turned the deaths into a referendum on the schools’ culture of achievement. Palo Alto, which lies in the shadow of Silicon Valley and is one of the wealthiest communities in the country, has long put enormous pressure on its children to earn the label “best and brightest.” Their success has been measured in the number of Advanced Placement (AP) courses they take, their SAT scores, and how many elite college acceptances they receive. In the wake of the suicides, Gunn’s administration and the larger community have begun to interrogate the damaging effects of this culture and realized that many students are forced to live up to unsustainably high expectations. Gunn has since pledged to “develop a culture that broadly defines and promotes multiple paths to success, embraces self-discovery and social emotional well-being, and values the love of learning beyond traditional metrics of achievement.” But while parents and administrators have wrung their hands over the climate their kids have been raised in, Gunn students themselves have led their own efforts to have their voices heard and valued. For them, as much as the achievement culture needs to be reconsidered, it’s the support the academic community provides that needs improvement. Students are asking whether their schools, which have led the nation in academic accolades, can turn themselves into models of mental health care.

When Gunn students arrived at school on the morning of Tuesday, November 4, the mood on campus was upbeat. The school was still high off its homecoming win the week before. At the beginning of first period, teachers in every classroom addressed their students, reading from a letter written by the administration: “Some of you may have heard that a young man took his own life last night. His name has just been released by the police, and it is with great sadness that I have to tell you that he is one of our current students, Cameron Lee.”

Many of Lee’s friends sat in complete shock. But soon the sound of screaming and weeping began echoing throughout the campus. Many of his closest friends left school. None of them saw it coming; he was the last person any of them suspected would commit suicide.

The day before, Gunn junior Kian Hooshmand was in a statistics class with Lee. They were sitting with a few other friends cracking jokes and talking about the Ebola epidemic. After school, Lee went to the gym to try out for the basketball team. By the evening, a few hours before his death, he and a few friends were reviewing a trade they were planning to make in their fantasy football league.

Short and lanky, Lee had a cherubic face and close-cropped black hair. At school, he was part of a clique called the Gunn Bike Crew (GBC), a group of nearly two dozen boys and girls who were among the most popular kids at school. He was also a high-achieving student. Friends told me that school came naturally to him, but he would do his homework late and pull many all-nighters and end up dozing off during class. Nobody really thought much of it. In the note he left for his family and friends, he wrote that it was nobody’s fault—not his family, friends, or school. He said he felt he didn’t have a future for himself in the world and he simply wanted to remove himself from it.

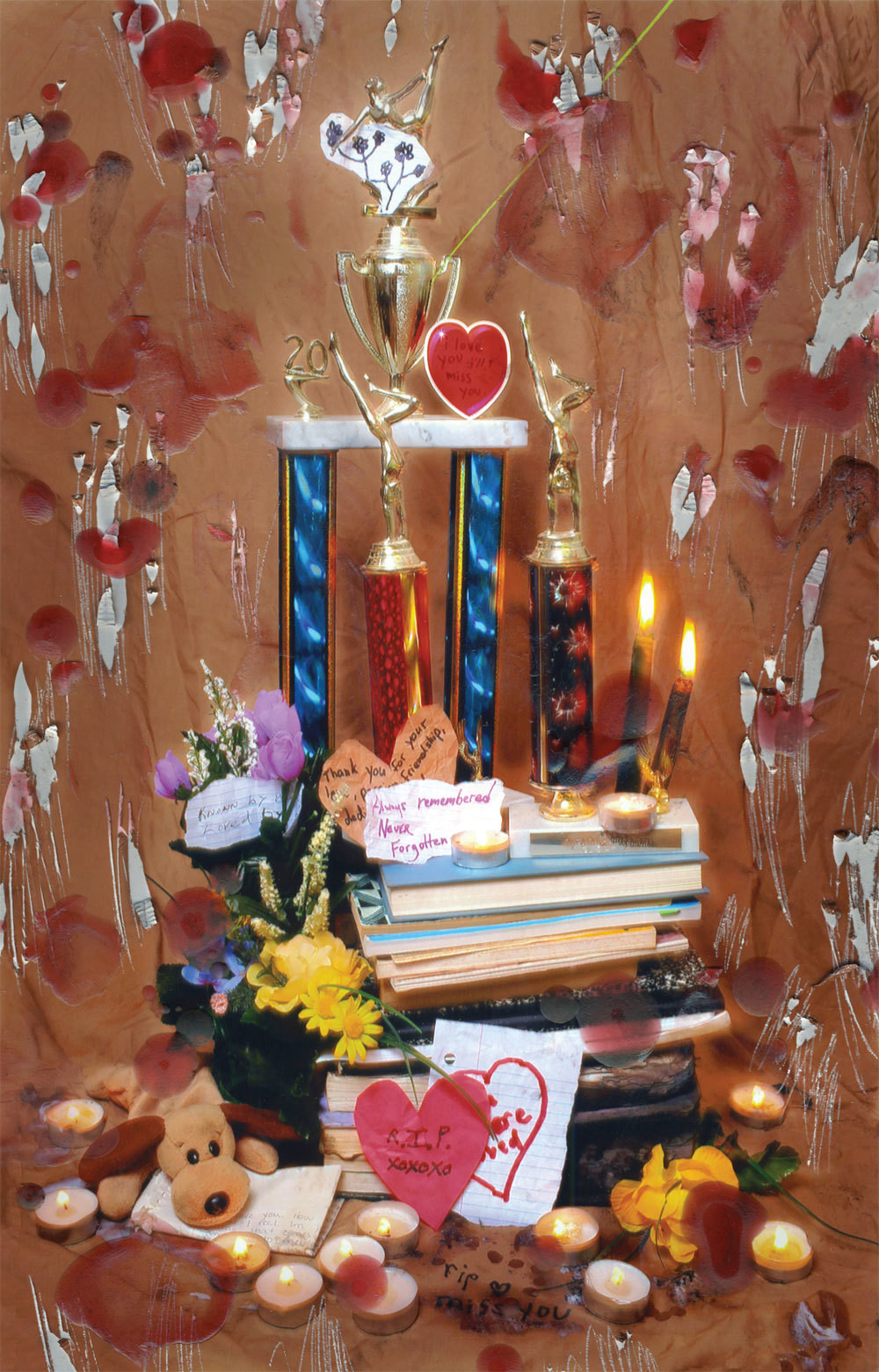

On Tuesday evening, dozens of Lee’s friends came to campus. Using chalk, they covered nearly every surface—sidewalks, walls, doors, bathrooms, and the parking lot—with phrases like WE LOVE YOU, CAM; PLEASE COME BACK; BALL IS LIFE; and FLUSH FOR CAM. One student told me they were “treating him like a martyr.” The next day, the administration, worried that the messages could be read as glorifying suicide and trigger suicidal thoughts in students who were already struggling with mental health issues, held a meeting with the student government. The school acknowledged that the chalk messages were part of the students’ grieving process, but they said the writing had to be removed. After school, it was power-washed away. The rest of the week the school was eerily quiet. Teachers gave students flexibility on assignments and tests, but a few continued with their lesson plans. Gunn junior Arjun Sahdev said, “You don’t have the time to mourn because you have to study for the exam the next day.”

Many in Palo Alto were especially tense because they were worried that Lee’s death had been a “copycat suicide” and evidence of a contagion in the community. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide contagion is “a phenomenon in which additional, often similar suicides take place following the report of a suicide.” A few weeks earlier, Quinn Gens had also taken his life. Gens was a freshman studying computer programming at Foothill College, a nearby community college, and had graduated from Gunn the year before. When a third student, Harry Lee (no relation to Cameron), committed suicide in January, there was increasing panic about a social contagion at Palo Alto high schools. His death happened on a Saturday, and students learned about it from Facebook and Twitter over the weekend, before it was formally announced on Monday morning at school. Once again, a letter was read to students, but it referred to Harry as “Henry.”

His friends described him as “hilarious,” “odd… in the most loving way possible,” and “a class clown.” He had once worn a horse mask to English class as a joke. In the senior poll, he was voted “most outrageous.” An obituary published on Palo Alto Online noted that he loved to dance and ride bikes, but it also mentioned his ACT score—35 out of a possible 36.

Then, in March, a Paly sophomore named Qingyao “Byron” Zhu took his life, marking the fourth and final student suicide of the 2014–2015 school year. His friends told me that he was taking many advanced classes, some intended for students in the next grade level. He was also involved in soccer and Science Olympiad. But looking back, they didn’t recall any warning signs.

By the time of Zhu’s death, parents and teachers had been scrutinizing their community and schools since the fall, and many had come to the conclusion that the intense pressure to succeed academically was driving the crisis. In all traditional metrics, Palo Alto high schools rank high. In 2014, Newsweek named Gunn America’s 38th best high school, and Paly was judged to be the 56th. More than 30 students in Gunn’s 2015 class and 24 in Paly’s were named National Merit Scholarship finalists, and many more had received what are considered the “golden” acceptance letters from the nation’s elite colleges. Though the community was proud of these achievements, some were quick to blame the suicides on the high-stakes “achievement culture” they created. But many ignored the broader mental health crisis and the lack of resources available to students that had also contributed. According to the 2013–2014 California Healthy Kids Survey, 16 percent of Gunn freshmen and 22 percent of juniors had recently “experienced chronic sadness/hopelessness,” and 21 percent of freshmen and 23 percent of juniors had thought about killing themselves in the past year. At Paly, the numbers were similar. Sixty-one Gunn students had been hospitalized or treated for suicidal ideation during the 2014 school year, a disturbing share of the school’s 1,900 students. In the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 4,600 people aged between ten and 24 commit suicide annually, the third leading cause of death for the age group.

By the time of his death, Harry Lee had been seeing mental health professionals to treat his clinical depression. Grant Fong, a senior at Gunn, said, “A lot of our friends considered it a failure of the system, as opposed to a personal failure. We had given him all the help he could receive. We set up therapist meetings. Unfortunately, none of them helped.” And after Lee died, his parents released a statement in the Palo Alto Weekly questioning the prevailing wisdom in the community about the suicides. “Our son struggled with depression,” they wrote. “He made it clear that the cause was not due to academic pressure at Gunn.”

In the fall of 2014, Gunn junior Manon Piernot was not in a healthy state of mind. She had been struggling with mental health issues for a while. Before high school, she was a student for many years at an international bilingual school in Palo Alto, which had fewer than 50 students in a graduating class. She loved the school and felt connected to her teachers. Her transition to Gunn after eighth grade was tough. At a school with a much larger student population, she felt lost and had only a handful of friends. One of the very first school assemblies was about college admissions. “I remember being really shocked,” Piernot told me. “I wanted to focus on learning things. I felt a lot of pressure to know exactly what I wanted to do.” She became involved in activities she had no interest in for the sake of upgrading her résumé.

When she was a sophomore and had to begin selecting courses for her junior year, she felt embarrassed that she wasn’t planning on taking an AP science course like many of her classmates. She loved sculpting and ceramics, and she intended to go to art school, a decision that few at Gunn seemed to support. By the end of the year, she started to feel depressed. Some of it had to do with problems at home, but most of it was affiliated with her feelings of inadequacy at school. Students constantly boasted about their grades and the number of AP classes they were taking. Their stress and college-oriented mindset began “rubbing off” on her. She told me that there was never an opportunity for her to candidly discuss what she was experiencing.

In November, the prevalent chalk drawings, the glorification of Cameron Lee’s death, and the school community’s failure to recognize what he had been going through triggered suicidal thoughts in Piernot. “Suicide seemed like a probable ending,” she said. Afraid that she might hurt herself, Piernot’s psychiatrist issued a 5150 hold—a 72-hour emergency stay at Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, a hospital just south of San Francisco. An ambulance was solicited, and Piernot was strapped to a stretcher and hauled to the emergency room. After waiting for a bed for eight hours, she was brought into the adolescent psychiatric ward.

Piernot ended up staying for two weeks. More than anything, she was relieved that she wasn’t at school. While there she participated in occupational therapy, worked on art projects, did yoga, meditated, and played cards and board games with some of the other adolescent patients. She wasn’t particularly impressed with her psychiatrist, who she said was not very helpful because he only asked about her mood and how she slept and then made adjustments to her medication. Most important, she soon discovered that a few of the patients were also students at Gunn, and for the first time in a long while she started to feel a little less alone. “Having a break from Gunn to understand my own priorities and goals saved my life,” she said.

These students were not interested in waiting for the adults to act. They made themselves into agents of change.

In November, disturbed by the suicides and the effects they had had on the student body, Gunn sophomore Martha Cabot and retired Gunn English teacher Marc Vincenti launched a campaign called Save the 2,008 to “bring a healthier, more forgiving life to our high schools.” The 2,008 refers to the number of students and teachers who remained at Gunn last fall after Cameron Lee’s death. Vincenti told me, “Save the 2,008 believes that high schools do not cause teenage despair nor can high schools cure teenage despair. But there is much that high schools can do to make teenage despair more bearable and survivable.” Cabot and Vincenti met for coffee to discuss ideas for the campaign, and at a school-board meeting a few weeks later, the duo presented a docket of six proposals, including trimming class sizes and amounts of homework; requiring meetings between parents, students, and guidance counselors to ensure that students who are taking AP classes are aware of what they are in for; decreasing the number of grade reports; banning the use of cell phones; and ending a climate of cheating by making consequences more explicit.

Many people in the community agreed that the academic environment had become toxic and unhealthy and supported Save the 2,008’s campaign. The obsessive preoccupation with where students would go to college had had a corrosive effect on their academic and social lives. Students end up pursuing classes and activities that look impressive on college applications, even though they may have no interest in them. And with admissions rates at elite colleges entering the single digits, the competition has intensified. Students who get accepted to those colleges are well respected at school. Alex Hwang, a senior bound for Rice University, told me, “Kids are judged by which college they are going to. I may know nothing about a guy, but I know where he’s going to college.” And the focus on grades had similarly started to distort students’ perceptions of their self-worth. Paly junior Sean Jawetz told me that when a friend says, “I failed that test,” he often has to clarify: “Did you ‘Palo Alto’ fail it,” meaning you got a B or worse, “or did you actually fail it?”

The Department of Pediatrics at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation tacitly came out for the Save the 2,008 plan with an op-ed published in the Palo Alto Weekly. “While we are not education specialists, as pediatricians we do recognize dangerously unhealthy lifestyle patterns and habits that are known to exacerbate stress, anxiety, depression, and physical illness,” they wrote. “These include chronic sleep deprivation, lack of unscheduled time for thought and relaxation, unhealthy eating habits, lack of exercise, and unrealistic pressures (real or perceived) to achieve. Those unrealistic pressures include excessive homework, overly ambitious course loads, and a seeming demand for perfection in grades, sports, and extracurricular activities.”

But many students felt that the campaign focused too heavily on addressing the school’s academic climate and not enough on the lack of mental health support available to students. In December, Gunn’s student newspaper, the Gunn Oracle, published an editorial signed by 36 of its 37 staff members, criticizing the campaign for “misperceiv[ing] the causes for student stress as purely academic” and disregarding the problems with mental health services at the school. While many in the community have supported the campaign, students at the school have mostly been critical, largely of the proposed cell phone ban and regulations of AP courses.

At Gunn and Paly, students have access to a free on-campus counseling program called Adolescent Counseling Services (ACS). One licensed therapist oversees a team of clinical interns who are earning counseling hours toward their marriage- and family-therapy license. But after the suicides, a negative stigma of mental health still looms, and many students are reluctant to use ACS. Students tell me they fear being seen as weak, overdramatic, or attention-seeking. Because of this, they are “very good at suppressing their emotions and struggles,” said Paly senior Andrew Lu. Paly junior Sean Jawetz also notes the pressure to win academically and socially while “maintaining an aura of being cool or chill.”

Then there’s the lack of mental health education. Students told me that there have been assemblies on sleep, for example, but few have attended because they don’t take them seriously. If you are not literate on the symptoms and causes of these problems, how can you possibly prevent and treat them?

Of the students who have visited ACS, few reported pleasant experiences. In the wake of the suicides, Gunn senior Jessica Lwi told me that the program, which is meant to help students handle stress and other issues, is ironically “a very stressful system.” When she went in for an appointment over the years, she often met with a different counselor each time, so she ended up having to re-explain her story. She felt the counselors were too busy and inadequately trained.

Lwi brought several of her friends who were suicidal or self-harming to ACS, but she says it’s actually made their situations worse because the school contacted their families, who then reacted poorly upon learning of their conditions. And the school never followed up with them later. Instead of waiting for students to come to them, Lwi argued, ACS should reach out to students who are expressing signs of mental illness. “Kids don’t always know how to ask for help,” she said. Part of the problem is that intern counselors only spend about a year at the school, so students have little emotional attachment to them. Principal Denise Hermann emphasized that the school’s mental health services were just short-term care and that families needed to follow up with their own health-care providers, but she said that Gunn would be hiring a full-time licensed mental-health therapist for the new year. Despite the flaws, Lwi still thinks going to ACS is better than getting no help at all, and she is considering pursuing a career as a mental health counselor when she gets to college.

There are a few encouraging signs that the community is coming around to recognizing and ultimately fixing these flaws. In March, the school board voted to allocate $250,000 of the district’s budget to hiring two more full-time therapists for the high schools, which will relieve the strained workload of the counseling staff. At Gunn, students took the matter of improving mental health into their own hands, organizing the Student Wellness Committee with the help of Herrmann. It organically grew out of their discussions on what needed to change at the school after Cameron Lee’s death. One of the things they set up was a referral box, which allowed students to anonymously refer their friends to counseling. “A startling number of people have told me that they wouldn’t talk to a counselor if they had a friend who was in trouble,” Gunn sophomore class president Chloe Chang Sorensen explained.

The committee also launched a mental health awareness campaign to educate students about causes, symptoms, and resources available to them. And finally, the committee collaborated with an organization called Youth Empowerment Seminar (YES!) to implement a mindfulness curriculum in physical education classes starting in the fall. These students were not interested in waiting for the adults to act. They made themselves into agents of change.

Following each of the suicides, the school district faced criticism from the community for not doing enough to prevent them. On top of that, there has been a sustained barrage of scathing media coverage in the New York Times, San Francisco Magazine, and NPR, sporting headlines like IN PALO ALTO’S HIGH-PRESSURE SCHOOLS, SUICIDES LEAD TO SOUL-SEARCHING; BEST, BRIGHTEST—AND SADDEST? and WHY ARE PALO ALTO KIDS KILLING THEMSELVES?

Some students, usually the ones who are high-achieving or in leadership positions in student government, have been defensive of Gunn at school-board meetings and in the press. They don’t deny that the stress and pressure exist, but they say that it’s all a normal part of high school and growing up, that it’s reasonable and only academic-related, and that Gunn isn’t a “place where people’s dreams die.” The students who are arguing that the amount of stress and pressure in Palo Alto are a normal part of high school and growing up likely don’t have a context of what life is like outside of a high-achieving community. It is not natural for stress levels to be this high and for this many students to be beset by mental heath issues. And so students who have that mentality have resisted proposals intended to relieve some of that pressure, like limiting the number of AP classes students can take. Gunn junior Kathleen Xue rebutted, “This is America. We should be able to choose how rigorous our workload is.”

In April, Paly’s online news publication, the Paly Voice, ran an editorial accusing the national media of perpetuating the “perceived image of the typical Palo Alto student as completely focused on academic success and nothing else” and inappropriately linking the suicides to stress at the schools. Gunn senior class president Mack Radin told me, “What I found at Gunn is that people do things very intensely. No matter what they are doing, they go all out.”

Over spring break in April, Palo Alto schools superintendent Glenn McGee announced that academic classes during zero period would be scrapped at both high schools, starting the next school year. Zero period was an option for students who wanted to take a class before the school day officially began. It came into existence after Gunn shifted its start time from 7:55AM to 8:25AM in 2011.

Proponents of this decision say that students were not getting enough sleep and sleep deprivation has a clear connection to poor teenage mental health. While it wasn’t advertised as a response to the student suicides, it was widely seen by the community as such. Supporters of the change cited a 2014 policy statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which recommended that schools start no earlier than 8:30AM.

Students, however, were overwhelmingly opposed to the change. Sorensen, the sophomore class president, conducted an online survey on zero period. Three hundred and seventy students responded, with 90 percent against the decision to ban academic classes during zero period. Students who had sports or work after school said zero period gave them more flexibility in their schedule, which actually reduced their stress. Some students said they preferred waking up earlier and getting a class out of the way to have a free period during the day. And some students who took a zero period said they went to bed earlier than the kids who didn’t. Yet there were a handful of students who agreed with the change. Some of their responses included: “Made my sleep a lot worse.” “Less sleep. Made everything more difficult. Impacted my grades harshly.” “It was hell to be honest. I skipped class because I could not get up in the morning. I was tired all day and was not able to function. I had to drop the class.”

Students were not willing to passively accept the superintendent’s decision. Two Gunn juniors, Ben Lee and Nina Shirole, co-founded the Palo Alto Student Union to advocate for and promote the student voice. They put up posters with the words SUPPORT STUDENT CHOICE, SUPPORT STUDENT VOICE all over Gunn. And many teachers supported their efforts. With the superintendent sitting behind him on stage, retiring Gunn mathematics teacher Peter Herreshoff said in a speech at graduation, “Your class this year witnessed the imposition of an unjust policy regarding zero period. Although it didn’t affect you directly, you united in solidarity with future graduating classes to oppose that policy. Although you didn’t win, yet, you learned about taking agency over your lives and working collectively to do that.” The student union considered holding a student walkout over the zero-period change but ultimately decided to host a sit-in at a school-board meeting.

A few weeks after the decision was announced, dozens of students attended a Tuesday-evening board meeting. This was the meeting at which zero period was originally meant to be discussed, but McGee had unexpectedly made a unilateral decision beforehand. One after another, students came up to the podium and blasted the superintendent. Gunn senior and school-board student representative Rose Weinmann called the move “misguided paternalism.” What students were most peeved about was that the zero-period decision was orchestrated in a top-down manner without their consultation. Ben Lee told me later, “We were blatantly disregarded by the community. It was good to show that we weren’t lesser beings. We were going to fight for our right to be heard.” He believes that the decision was rashly made to “appease a few people.” Shirole also thinks it’s a contradiction that physical education and broadcasting classes during zero period will remain when the underlying intention of the change was to help all students get more sleep. And she says the research on later start times does not “account for the element of choice,” as zero period is optional.

“We were blatantly disregarded by the community. It was good to show that we weren’t lesser beings. We were going to fight for our right to be heard.”

Later, at a May meeting, board member Camille Townsend took McGee to the woodshed: “I can assure you this, that in my twelve some years on the school board, there has never been a decision made like this with so little information that the board has been able to discuss.” She continued, “Why is there secrecy behind this? Why was it that during break I received a directive from the superintendent? That is not how we do business here in Palo Alto.”

Besides changing zero period, at another May board meeting, the school board approved the new block schedule at Gunn for the fall, in which students have fewer but longer classes in a day (Paly already had block scheduling). The purpose is to lighten the amount of work and studying that students need to do each night and thus lower their stress levels.

Many in the community appreciate the district for their efforts after the suicides, but there are others who believe it is simply making changes for the sake of change and not truly addressing an academic environment obsessed with grades, test scores, and college admissions.

Weeks after her stay in the hospital, Piernot was “still wallowing in depression.” Then, at the end of January, Harry Lee’s death re-triggered her suicidal ideation. She was given another 5150 and returned to the same hospital. This time her psychiatrist had lengthy, fruitful conversations with her about the challenges in her life. It became clear to her that she needed to start living in the present in order for her health to improve and to get back in touch with herself—”knowing who I was.”

“In our minds, we like to do some fortunetelling,” she said. “We often imagine the worst-case scenario, which is harmful. We feel inadequate. What if I don’t get into this college? What if I don’t get into my first choice? What if I don’t get a scholarship? Which ends up hindering your present. You aren’t doing things in the present. You’re thinking more about the future. You’re focused on getting a good grade in order to get into college.”

After the two-week visit to the hospital, she joined an outpatient program for three hours every day after school for eight weeks in which she engaged in many types of therapy. “We discussed mindfulness and destructive behavior and how to get out of them,” she said. “It helped me to separate myself from others. I was focused on myself and no one else. I stopped taking on others’ problems and solved my own.”

At school, Piernot started putting this new mindset into action. Whenever a student began talking about grades, she plugged her ears and walked away. And she said, “I stopped worrying about grades. It was so freeing to me.” She added, “My aim is to be happy now. If I get bad grades, I don’t give a shit.”

If you are concerned about your mental health or that of someone you know, visit the Mental Health America website.

More

From VICE

-

VICTOR HABBICK VISIONS/GETTY IMAGES -

Gavin Rossdale in the kitchen (Credit: Courtesy of Gavin Rossdale) -

Screenshot: Riot Games