“Just so we’re both completely clear: We’ve spent most of the week flying to Australia to stand in line to buy a phone we’re not sure we’re going to get,” I say to Kyle Wiens, the CEO of iFixit and the person whose plan this was. It crosses my mind that there is a perfectly good Apple Store three minutes from my office.

We have the order confirmation: One iPhone X, to be sold to us at 9:30 AM at the Castle Towers Apple Store. Still, it is entirely possible that there might not be a phone. It’s happened before.

Videos by VICE

“It’s completely ridiculous,” Wiens responds. “It’s a big gamble, right? If there’s a disaster and the store doesn’t get their allotment—at that point, you have to turn to the people who got them and offer stacks of cash.”

We’ve brought $2,000 just to be safe. I know that we probably won’t even turn the phone on, that it’ll be a good day if we buy the most coveted device on Earth and immediately break it.

“We’re going to have one of the first iPhones in the world, and we have no intention of using it,” Wiens says.

*

Every iPhone is made up of more or less the same components. There’s the ones we can see: the camera, the Lightning Port, the screen. And the ones we can’t: the battery; the wifi, bluetooth, and cellular chips; the storage, processor, and RAM; the Logic Board; and hundreds of tiny chips and sensors that control everything from touch input to charging speed. They form, perhaps, the most successful commercial product humans have ever made. But without actually opening it, we have no real way of understanding how this all-powerful device works or knowing anything about these components besides the limited information Apple tells us.

It may sound absurd, but the most interesting and arguably most important thing to happen on iPhone release day is not the release of the phone but the disassembly of it. The iPhone teardown, undertaken by third-party teams around the world, provides a roadmap for the life of the device: When you inevitably break the screen, will it be easy and inexpensive to fix? Are there design flaws that will potentially cause widespread problems, such as the iPhone 6’s bendgate? And, most importantly, who made the iPhone?

Very little inside the iPhone is actually made by Apple. In the iPhone X, Samsung makes the OLED display, Qualcomm makes many of the chips, and much of the iPhone’s famous camera is made by Sony. Because Apple will sell roughly 200 million iPhones this year, what’s in the iPhone is a crucially important question for the worldwide economy.

“The teardown is the Super Bowl for the tech supply chain,” Daniel Ives, an Apple analyst, told me in a phone interview. “Whether you’re in the iPhone X or not—it could ultimately be the birth of a new company or the death of an old company.”

Apple did not respond to my request for comment, but the company rarely offers any photos of the inside of its devices, and certainly not on the day it’s launched. For that, we have to rely on third-party teardown teams.

“They’re off in a distant land with a limited tool set, and we’re back here telling them what’s happening”

And so every iPhone release day, stock traders, gadget geeks, engineers, and even a lot of people at Apple itself frantically refresh Twitter, RSS feeds, Google Alerts, Reddit, YouTube, and Weibo in an effort to learn what’s inside the device. Consider, for example, the iPhone 3G, which contained three different components made by a small, Oregon-based company called TriQuint Semiconductor. Moments after the teardown went live, TriQuint’s stock price jumped by 60 percent; the company had been deemed good enough to be used in an Apple device.

“If the iPhone sells 80 million units and a company making a chip in there sells it to Apple for 40 cents, well, 40 cents times 80 million is a lot of money,” Stacy Wegner, a teardown specialist at Teardown.com, told me. “That’s the kind of math we start talking about.”

If the iPhone teardown is so important, I wanted to see it firsthand. And so I flew across the country, and then across the ocean.

*

iFixit didn’t invent the teardown, but the company has become by far the most popular and well-respected group of teardown artists in the world. The company, based in a two-story reclaimed auto repair shop in San Luis Obispo, California, treats its iPhone teardown like a space launch. The “home team” camps out at its headquarters, while a teardown engineer, a photographer, and a coordinator are dispatched to far-flung locales like Tokyo, Sydney, or, in earlier years, London. The away team—this year made up of Wiens, teardown engineer Jeff Suovanen, and photographer Adam O’Comb—methodically works through the iPhone and sends photos of it back to headquarters, where engineers and analysts try to identify what, exactly, is going on in it.

Because the iPhone X is released at 8 AM local time all around the world, flying to Sydney buys the team 16 “extra” hours to tear down the iPhone before the East Coast launch. The goal is to be completely done with the teardown by the time the iPhone is for sale in New York. The team, I’ll learn, needs just about every minute of that head start.

“It’s like Apollo 13, but less disastrous,” Sam Lionheart, a technical writer at iFixit who flew to Sydney to tear down the iPhone 8 earlier this fall, told me. “They’re off in a distant land with a limited tool set, and we’re back here telling them what’s happening.”

This time-zone gaming is necessary to even have a remote chance of consistently getting the first iPhone teardown on the internet. In the early days, iFixit was regularly scooped by Mitsunobu Tanaka, a Japanese biotechnology researcher at the Red Cross who tore down iPhones as a hobby.

“It was always a race between us and him, and he had the time zone advantage of being in Japan,” Wiens says. Tanaka eventually quit the first-day teardown game because iFixit started flying people to Tokyo, Sydney, and Melbourne to better compete with him. Two teardowns just didn’t seem necessary.

In the years since, new competitors have come from around the world. The first iPhone 7 Plus teardown came out of a Vietnamese forum; the first iPhone 3GS teardown was done by a team in Poland; increasingly, repair shops in Australia have gotten in on the game, too.

“At the moment we don’t have an arch nemesis,” Wiens says. “Instead, you’re competing against the entire world. All it takes is one person somewhere to get the phone.”

Wiens had “Plans A, B, C, and D” for getting the phone. Plans B through D all involved passing a large pile of money to someone in line.

The iPhone 4S teardown field trip was a bit of a catastrophe—Wiens flew to Tokyo to tear down the phone, was told in line by a reporter that someone had managed to get ahold of the phone early and had already torn it down, and Wiens wasn’t able to buy one anyway. The iFixit team in California, meanwhile, managed to pay several thousand dollars to someone on Craigslist who had the phone before its release date because of a FedEx error that caused the phone to be delivered early.

Sometimes, the race comes down to who reaches the end of “live” teardowns first. When the Apple Watch was released in 2015, an Australian repair shop uploaded its first few teardown photos before iFixit. But the watch had a brand new, tiny screw that hadn’t been used in an Apple product before. Without a screwdriver that could remove it, the Australian team was stuck and never finished the teardown. iFixit’s engineers improvised by filing down a different screwdriver and were able to complete the teardown.

One advantage iFixit has is that the company’s primary mission is to make it easier for the average person to disassemble and repair their electronics. Its main business is selling specialized tools and replacement parts specifically for teardowns and repairs, and so many of its engineers have helped craft the tools it will use to open up the iPhone X. Its headquarters features both a tool laboratory and a parts library that could easily be used to build just about any popular electronic device released in the past 10 years from scratch.

My goal from the outset was to embed with the team that would win the iPhone X teardown race, and iFixit seemed like my best bet.

*

In the days leading up to the iPhone X release, I scouted potential competitors. My early findings were promising from an “I hope I’m not going to Australia for no reason” standpoint. An Australian repair shop that has done several teardowns told me preorders sold out before it could get a phone. A French team called SOSav said that, given the quantity of teardowns, it was internally debating whether it should even bother. After much debate, it decided to go ahead with one: “Teardowns are a prerequisite nobody can avoid,” a spokesperson for the company told me in an email. The good news for iFixit, though, is that SOSav would not be leaving France.

“We haven’t yet felt the need to go to countries with an earlier release than France,” SOSav CEO Mikael Thomas told me. “Personally, I think setting off to another country for the repair would completely contradict our aim to limit our carbon footprint. Putting our team on a plane would make us real kerosene guzzlers.”

I had been assured that iFixit would get a phone, in Australia, within the first few hours of its release. An internet outage at the iFixit office prevented the company from pre-ordering the phone in Sydney, but a friend of the company had come through with a 9:30 AM reservation—just an hour and a half after the phone went on sale. The plan was to show up to the Apple Store early and bribe someone in line to switch reservations.

Wiens had “Plans A, B, C, and D” for getting the phone. Plans B through D all involved passing a large pile of money to someone in line.

The night before the teardown, I met with the iFixit team at Circuitwise, a circuit board manufacturer in an office park in suburban Sydney that owns one of Australia’s only electronics X-Ray machines, employs highly skilled solderers, and happens to be located just 15 minutes from the Apple Store. The first floor of the facility is filled with robots that automatically place nearly microscopic chips on circuit boards, robots that bake and solder the chips, and humans clad in anti-static jackets that make sure the robots aren’t screwing up.

Upstairs, iFixit has taken over a conference room. The boardroom table is covered with all manner of adapters, Lightning and Thunderbolt cables, tools, old iPhones (including the original iPhone) for comparison shots, a few bananas and pastries, and a bunch of laptops, each of which will soon be assisting in a critical part of the teardown. It is immediately apparent that iFixit is highly prepared.

It’s around this time that I notice iFixit has already lost

“We have two suitcases of tools, so we can double our chances in case our luggage gets lost,” Lionhart says. The suitcases are described to me as if they were teardown go bags, ready to be deployed in case of any smartphone emergency.

It was appropriate, I thought, that as Circuitwise built electronics, iFixit would be tearing into them.

*

Plans B through D weren’t necessary, and Plan A went much better than anyone could have hoped. The Apple Geniuses didn’t seem to care that iFixit’s reservation time was an hour and a half after the store opened. Instead, Wiens was the second person let into the Apple Store and the first to check out. The transaction was completely over by 8:03 AM—it is entirely possible, probable, even, that Wiens was the first person on Earth to buy an iPhone X—and the team sprinted through the mall to the rental car. The iPhone remained in its box during a harried ride to Circuitwise filled with nearly missed turns, game planning, and borderline reckless driving.

We don’t park the car; Wiens halfway pulls into a spot and runs into Circuitwise. The teardown is on.

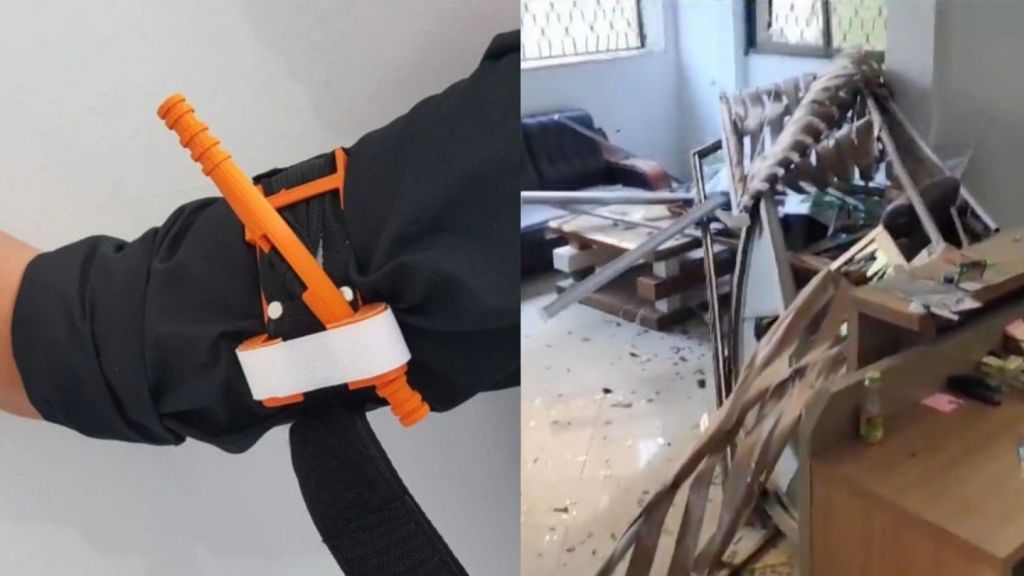

It’s around this time that I notice iFixit has already lost. Someone on Weibo had posted a short video of the iPhone X’s internal components hours before the phone went on sale anywhere on Earth. The phone had “fallen off the back of a truck,” repair-industry speak for unaccounted-for phones that disappear from factories. The video had gone to the top of the Apple subreddit, and MacRumors, a popular Apple blog, had already picked up the video. iFixit had been scooped before it even started.

I quickly realized, though, why the iFixit teardown is one of the few teardowns that actually matters. There’s a huge difference between seeing a couple seconds of grainy footage and doing the sort of teardown that has the ability to affect the global economy.

iFixit’s teardown isn’t just about taking the device apart; it’s about trying to identify every single chip within the phone, its function, its manufacturer, and its likelihood to make any given phone repair easier or more difficult. For the next 10 hours, Wiens and his team methodically disassemble the phone. They x-ray some individual components in an attempt to learn their provenance and call the world’s foremost chip analysts and experts to run part numbers or brainstorm what unfamiliar chips could do. They get help from Christopher Jimenez, an employee of Creative Electron, the company that makes the x-ray machine. Jimenez gave iFixit his preorder and flew to Australia to operate the machine. An employee of Circuitwise used an industrial soldering machine to separate the two Logic Boards from one another.

After months of iPhone X hype, it turns out that this iteration of the phone actually is quite a leap forward. There’s seemingly much less stuff inside the iPhone X than in previous devices. Apple managed to shrink the Logic Board—the brains of the computer—to an absurd degree by stacking two chips on top of each other. According to iFixit’s analysis, the board occupies just 70 percent of the real estate that the iPhone 8’s Logic Board does, which allows for a battery that takes up most of the interior of the device. This is a significant step forward in Apple’s never-ending quest to make its phones thinner, lighter, and faster—if you can get rid of all the separate components that make up a phone and put them onto ever-shrinking chips, you can reach a point where the functional bits of the phone don’t get in the way of Apple’s obsession with design.

“The eventual trajectory of this is you have a screen, a battery, a camera, and a chip,” Wiens said.

Ten hours after he bought the phone, the brand-new iPhone X is lying on the boardroom table, spread out into its component parts. The phone will never work again, a sacrifice made in the name of exploration.

“Taking things apart is interesting and fun. Every time you take something apart, you learn something about what makes it tick,” Wiens says. “We want to know what’s in the phone, and we know we’re going to write a repair manual so people can fix it themselves. We look at the teardown as an exploratory process, a public process of getting inside and learning how it works.”

The teardown may influence the stock market, but at its heart, it’s an exploration of how accessible our gadgets are to us. As companies increasingly move toward inscrutable and inaccessible systems and away from the very idea that you own the things you buy, flying halfway around the world to open a device that the manufacturer would prefer stay closed doesn’t really feel crazy at all.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.