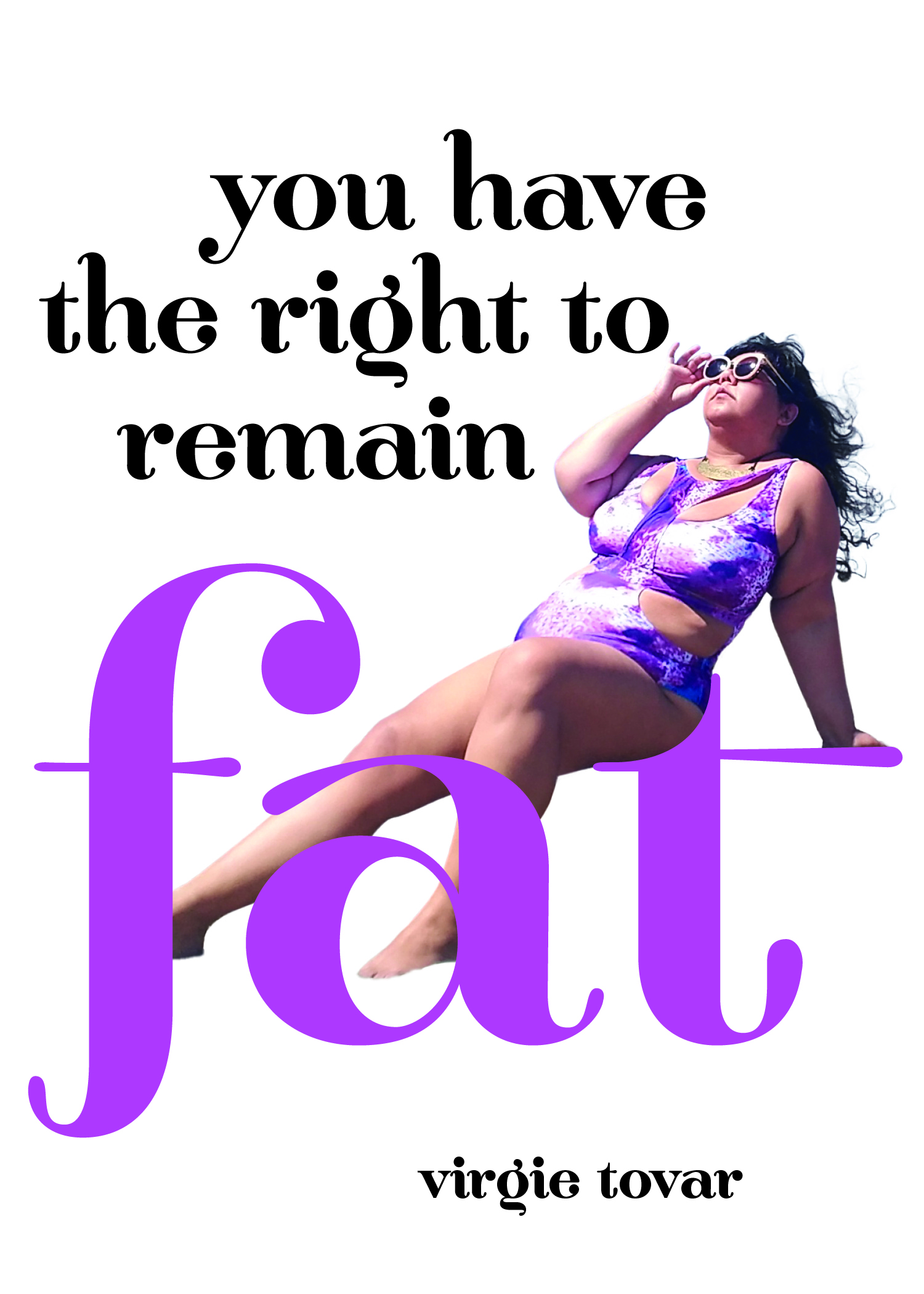

Author and activist Virgie Tovar grew up as a fat girl believing that her body was something to be fixed. Ever since she overcame that lie, she’s been working to make sure that others don’t believe it, either. Today, she’s an expert at deconstructing the toxicity of diet culture, teaching people how to unlearn fatphobia, and fighting moral judgements associated with food. In her new book, You Have the Right to Remain Fat —coming out in print on The Feminist Press on August 14—she does all that with refreshing criticality and resonant personal reflections. Below, read an excerpt from the chapter “In the Future, I’m Fat.”

I write very good personal ads. I know that the age of the ad has largely come and gone, but I’ve always loved the idea that my first interaction with someone was linguistic rather than visual. In the realm of digital romance, language is used in a very pragmatic, outcome-driven way. People tend to focus on statistics, measurements, desires, goals, and hobbies. My ads are less like lists and more like full-length confessional manifestos. All of the distance and suspicion I convey while on dates is counterbalanced by the intimate nature of what I’ve written before the date.

Videos by VICE

Men in San Francisco, I’ve found, tend to be very intrigued by my ads. I’ve noticed that I’ve developed a regional voice because when I place the same ads when I’m traveling I often get emails that rhetorically pose questions like, “What is wrong with you?” My ads detail not only where I live and what I like but also my passion for nail polish, jasmine and gardenias, tiramisu and cheesecake, particular scents I find evocative of particular times, the way my face looks in the morning—the fact that I am incapable of actual intimacy but am very invested in the quickly won, shallow intimacy that can only be had between strangers who like the idea of having sex with each other, probably, once.

For years and years, I could not accept the possibility that I would be fat forever.

I had written one such ad in 2014 and attracted a very eager doctor dude. After exchanging a few emails, he asked for “permission” to “aggressively pursue” me. He sounded like a psychopath and so naturally I was interested. I’ve noticed men in traditional professions are skittish about sharing what exactly they do. So it wasn’t until we were at this Peruvian restaurant chewing on tiny, crispy octopus tentacles near the Haight that he divulged that he was an “obesity researcher.”

He followed this up quickly with telling me that he was a big fan of my work. The whole thing was very confusing. Thankfully, more than connection, I love a deeply alienating weirdo who has watched YouTube videos I made in my bedroom about how to turn garden accents into hair accessories or how to “sluttify” any outfit with only scissors and the will to release any claim to respectability. I’m not sure exactly what kept me on that date: perhaps it was that I wasn’t woke enough to see what he represented, perhaps I liked what he represented, perhaps I was willing to give him a pass for pathologizing people like me because he was fat too.

He had an interesting story. He said he had always identified as an “overeater.” He said he liked food a lot and ate frequently, and had always been thin. All of a sudden, at around thirty-five, something kind of unexpected happened. His behavior didn’t change, but for reasons he couldn’t quite grasp he went from being a thin person to being a fat one.

On the date he asked me, “Wouldn’t your life be easier, though, if you were thin?”

The answer to this question is simple: no.

My life wouldn’t be easier if I were thin. My life would be easier if this culture wasn’t obsessed with oppressing me because I’m fat. The solution to a problem like bigotry is not to do everything in our power to accommodate the bigotry. It is to get rid of the bigotry.

In the dreams I have of my future, I am fat. This simple fact was hard won. For years and years, I could not accept the possibility that I would be fat forever. I had internalized fatphobia so deeply that I believed my life wasn’t worth living if I wasn’t going to someday transform into a thin person. I didn’t think I deserved to have good things because I was fat. Like many women, I had a wardrobe filled with clothes that didn’t fit me. I didn’t let anyone take photos of me. I cut up the pictures of me that did end up surfacing. This inability to see yourself in the future is a product of believing there is no room for you in the culture that surrounds you. The future, it turns out, is a lot about the present.

The allure of diet culture is a life lived in the future. The future is a hermetically sealed unreality that possesses none of the limits—or the potential for magic—of the present. The present is messy, sweaty, filled with longing and sometimes anger and sometimes sadness. The present holds your body in all the imperfection that makes it real.

The future represents possibility to many.

My obsession with my thin future was about disembodiment. It was about disassociating completely from myself, the present and my body. In the narrative I created about the future, I was the author of my life. I deeply longed to feel that sense of ownership, but I didn’t know how to access it because I had been emotionally battered so severely by a fat-hating, woman-hating culture.

You cannot earn freedom through conformity.

I had felt that I could earn that authorship through compliance. I couldn’t bear the reality that I was living in. So I jettisoned my emotional self out of the present and into another time. It was a beautiful time filled with all the things I wanted most, which I felt I didn’t deserve because I wasn’t in a “good” body. I violently deleted my true self from the story by always focusing on an anesthetized future filled with other people who also knew how to conform successfully. I never thought of those people as good or bad. I thought of them as real, and my fat self as an in-between space I was temporarily occupying. I became complicit with them in the destruction of my past and all that my failure represented: my undisciplined body, my lack of feminine grace, my inability to be white enough, my rage, and my inability to assimilate completely into American culture. I didn’t think of it that way back then, but that was the truth of it.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

I conceptualized that in my future I would be free because I would be thin, but I was wrong. In that future I imagined, it’s not that I was free. Far from it. Any future that doesn’t center the eradication of oppression and collective freedom is not a future worth imagining. In that future I imagined I was no longer subject to fatphobia because I was thin, but I didn’t realize that it wasn’t fatphobia that had gone away. There was no me. The fantasy of and longing for a thin body became a way of making the oppression that was breaking my heart, breaking me, more bearable. It didn’t occur to me that there was anything wrong with the idea that anyone—let alone an entire culture—would bully me into believing there was something fundamentally wrong with me and that I needed to change it. It never occurred to me that the standard of normal to which I was subscribing was violent, and always had been. I thought I could earn my way out of oppression, but I realize now that nothing is farther from the truth. I had lost sight of my right to freedom and my right to live a life free from oppression. I had lost sight that those things are my born right.

You cannot earn freedom through conformity. You cannot buy your way in. And we can only claim it when we recognize it is already ours.

More

From VICE

-

Tru-Tone -

-

Image: 20th Century Studios -

Screenshot: Blizzard Entertainment