The title of artist Michael Rakowitz‘s first major exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) is Backstroke of the West. It’s a mistranslation of Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, used for a Chinese bootleg version of the film and probably gleaned from Google Translate.

If Star Wars is an unexpected entry point for a show largely about the modern Middle East, Rakowitz makes a great case for the ways George Lucas’s films influenced Iraqi military actions during Saddam Hussein’s regime. In The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own (2009), the artist details how Saddam’s son Uday became an avid fan of Star Wars, tracing parallels between the series’ plot and Uday’s demise at the hands of American troops. He explains that Uday designed the uniforms worn by the Fedayeen Saddam, an elite Iraqi militia, to look like Darth Vader: their helmets are a replica of the villain’s iconic headpiece. And Rakowitz shows us how a war monument in Baghdad called the Hands of Victory uncannily resembles the poster design for The Empire Strikes Back.

Videos by VICE

This installation is just one of eight ambitious, drastically different Rakowitz pieces on view at MCA through the spring. But themes of translation and popular culture pop up again and again in his work. They’re concepts the artist gravitates to for their transitive properties, crossing cultural and political divides and offering an accessible touchstone for American audiences who are largely disconnected from the realities of life in the Middle East.

His acclaimed work The invisible enemy should not exist (2007-ongoing) is an attempt to recreate all the artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq after the 2003 American invasion. The Breakup (2010) draws parallels between the failed Israel-Palestine unification efforts in the late 1960s and the breakup of The Beatles. Enemy Kitchen (2017) is a pop-up food truck serving Iraqi-Jewish cooking made from Rakowitz’s mother’s recipes. Meals are served on paper plate replicas of the china looted from Saddam Hussein’s palace, which the artist subsequently bought on eBay. (An earlier iteration called Spoils used the real china plates. They were seized by federal marshals and returned to Iraq.)

In honor of the sweeping show at MCA, VICE sat down with Rakowitz in Chicago to discuss the artist’s cultural heritage, the conflicts that have shaped and wounded Iraq, and how he engages with global politics as well as personal histories through his art.

VICE: What was it like to spot Saddam Hussein’s dinner plates on eBay?

Rakowitz: At the start of the Iraq War, it was the existence of an antiquities art market that allowed for the National Museum of Iraq to be looted in the first place. Those artifacts ended up in places like Sotheby’s and other auction houses, but in the early days of the looting, some of them ended up on sites like eBay.

I had been seeing on eBay that Saddam Hussein’s personal china was available from various venders. One of them was an American veteran based in Baghdad at the time. He had gotten them from Iraqi sellers who had looted the palaces in the aftermath of the shock-and-awe campaign and were using his plates as their own dinnerware. I thought it was so fascinating for these objects of power to be dispersed to the Iraqi populace.

The other seller was an Iraqi living in Michigan whose father was a high-ranking officer in the Republican Guard. I thought these two sources were really interesting. We have an American veteran who’s there, and an Iraqi refugee who’s here.

Watch more from VICE:

How did their perception of the origin of the plates differ?

The only reason why those plates would ever make it to somebody’s table was because the American invasion overthrew this leader. His plates had a different meaning for Iraqis, because there was a very complicated relationship with Saddam that wasn’t rosy. But the fact that it was a Western power that came in and yet again imprisoned or executed an Iraqi leader was a repeat of the British and Western-backed coups that happened in succession throughout the 60s and onwards.

It was an amazing realm to insert myself into, in terms of research. American soldiers were the most embedded, yet no one asked them about the Darth Vader helmets. [The soldiers] were the ones who did the sleuthing, to figure out that Saddam and his son were huge science fiction fans.

I wanted to talk about that science fiction aspect, because it’s a big part of your exhibition, with huge lightsabers and Darth Vader helmets lying around. Can you elaborate on the connection between Star Wars and Saddam?

In 1994, when I was studying public art, I bought a book called The Monument by Kanan Makiya with an image [of the Hands of Victory] on the cover. It reminded me of the poster I had from The Empire Strikes Back that was given away for free when I saw it as a kid. It hung over my bed. You have this looming evil-doer Darth Vader with two crossed, red lightsabers hovering over the protagonists in the foreground. I immediately thought of those crossed lightsabers when I saw the monument of the crossed swords.

I ended up in Beirut in 2008 for a conference, and this incredible art historian named Nada Shabout was giving an overview of Iraqi art, and she talked about the Swords of Qādisīyah, the Victory Arch. And on the eve of the first Gulf War, the night before it was supposed to begin on January 15, 1991, Saddam actually had the Iraqi army marching underneath the crossed swords to the theme song from Star Wars, which was played over and over again and televised across the country. I was like, Whoa, that’s two connections!

You’ve gone to great lengths to recreate the artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq. Why?

It’s meant to explore pathos. Everybody that I’ve spoken to or read about, it doesn’t matter if you were for the war or against the war, when the Iraq museum was looted, it was a catastrophe. Something that was a local problem suddenly became a global problem, a human problem.

You’re talking about the first writing, the first code of urban laws. I thought that was an event that might unify. And it’s naive, but if you could have this outrage over stolen artifacts, what about the missing and stolen lives and dreams of the Iraqi people? The interruption that this country has experienced is unimaginable, and the people who give up everything that they were striving for to become refugees just trying to survive… We don’t think about those things enough. So I was a little bit outraged that the outrage ended there, with the objects, and that it didn’t translate.

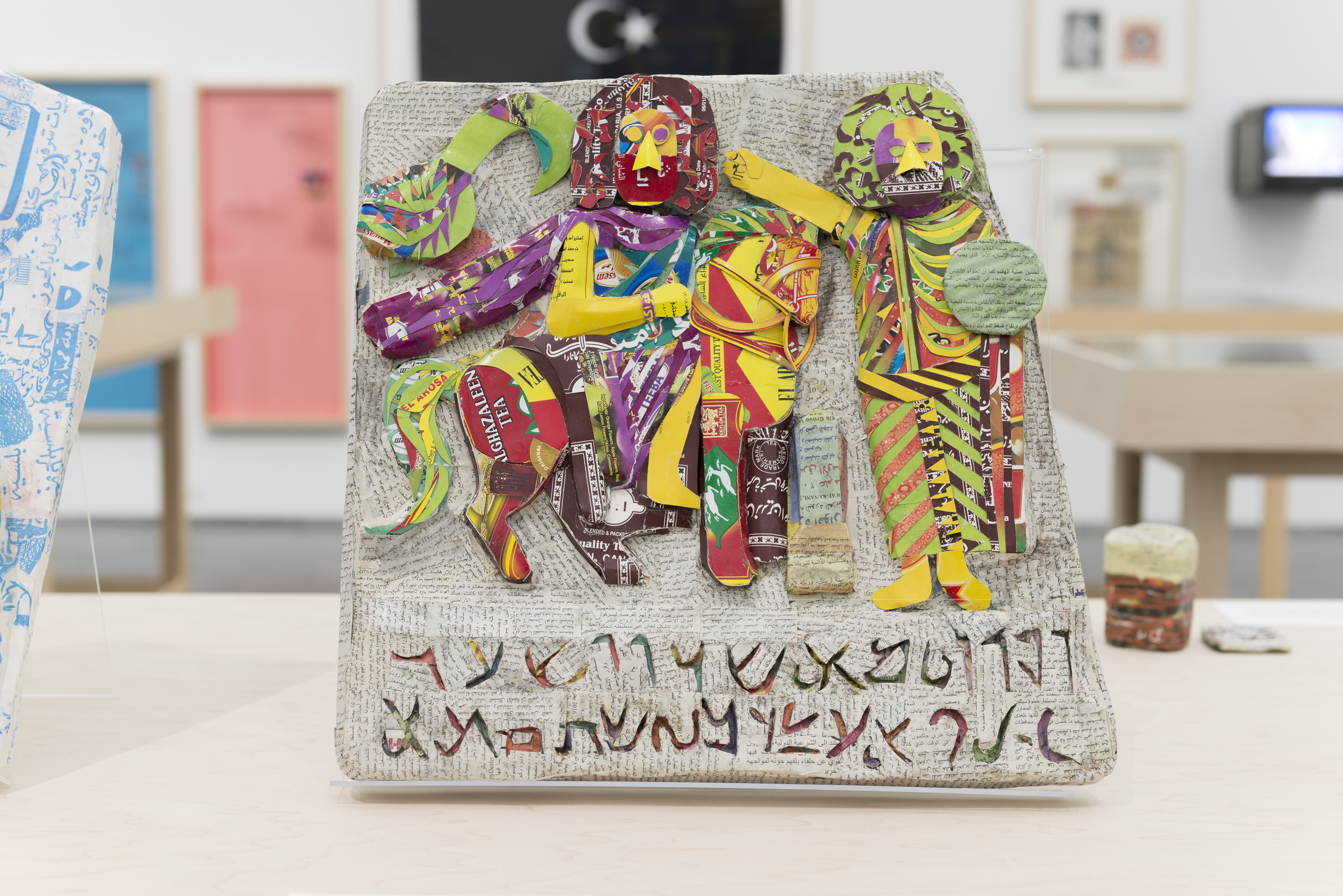

Is that why you decided to recreate the objects using pieces of the diaspora, Iraqi food labels?

Yes, exactly. I thought about making something that lost its provenance, by being looted and being sold on the black market. It is about that artifact being elsewhere, the same way Iraq is elsewhere. And it’s a violent push to elsewhere, it’s not a choice, and so now you look at those artifacts and it’s the fragments of this cultural visibility that are being enlisted to make things that are now invisible.

I insist on the things not being made out of limestone or alabaster, but being made out of materials that are urgent and itinerant, that will more or less be the effigy or the apparition of the thing that’s been lost. I feel like I’m making the ghost.

What do you hope Americans gain by being exposed to the costs of this conflict?

The Iraq War was such an unpopular war. The fact that it could go on the way it did is an immense problem that I feel like I grapple with every single day. I would like to be part of a world that doesn’t allow it to happen again.

I do think that if we demand a better, kinder, and more hospitable place, we can construct that through our acts and through our actions.

Follow B. David Zarley on Twitter.