At a campaign rally earlier this week, Georgia lieutenant gubernatorial candidate Sarah Riggs Amico urged the crowd to double check their ballots on Tuesday. More than one person had told her they’d had trouble during early voting: When they had tried to select the Democratic candidate on their electronic ballots—which rely on touch screen technology—the computer changed it to a vote for the Republican candidate.

“Have you ever heard of the reverse?” Riggs Amico asked. The group of about 50 people, sitting at green tables in a Mediterranean restaurant and market, shifted in their chairs. “A Republican vote turning into one for a Democrat?”

Videos by VICE

“The term they use for that is ‘slippage,’” Jessica Zeigler, the co-lead of local grassroots organization Indivisible Georgia’s Sixth, said Monday. She was sorting canvassing materials on a brown suede couch in a coffee shop just one mile away from where Riggs Amico had spoken the day before. “It could affect Republican votes too—but the Republican candidate is always listed first on the ballot.”

“Slippage,” David Becker, the executive director of the Center for Election Innovation & Research, told me later that evening, is a voting error that happens when “you have an old touch screen that’s miscalibrated: You touch it and it doesn’t register your vote correctly.” Georgia was the first state to adopt the touch-screen voting machines in 2002; now it remains one of just five states that use electronic-only voting, giving voters no option but to use the same voting machines as 16 years ago.

“The machines are so old and out of date,” Zeigler continued. “It’s the biggest obstacle we have.”

This year, Georgia has become ground zero for attacks on voting rights. In his current role as secretary of state, gubernatorial candidate Brian Kemp purged more than 300,000 Georgia voters from the rolls in the weeks leading up to the midterms, and placed 53,000 others—most of them Black—on a “pending” list, preventing their registrations from going through. The state has also been through a legal battle over its electronic voter system, whose outdated technology has been said to produce ballot errors of the kind Riggs Amico and Zeigler describe. And on Monday, Kemp announced he was launching an investigation into the Democratic Party for cyber attacks on the state’s election apparatus, an allegation for which he offered no evidence.

Throughout the morning, canvassers had been flowing in and out of the coffee shop where Zeigler was stationed, grabbing flyers and campaign door hangers from her and Amy Nosek, her co-lead, before hitting the pavement in Georgia’s 6th congressional district. Zeigler provides canvassers with a set of talking points about the Democratic candidates in the district. She tells them to focus on the issues—health care, education, and gun control. But she also has to prepare them for the possibility that residents will tell canvassers that their votes don’t matter, or argue that their ballots will be tampered with anyway.

“We’re telling people, ‘Even though it’s precarious, your vote counts now more than ever before,’” Zeigler said. “If we just overwhelm the vote as much as possible, that’s our path to victory.”

But at times, the specter of mass voter disenfranchisement has tempered the palpable enthusiasm and excitement suffusing Georgia this election cycle.

The woman at the front desk of a hotel in Marietta told me she’d seen friends on Facebook talking about their electronic ballots glitching in favor of Republicans. A waiter at a diner across town said he’d heard of people having problems both ways: Democratic votes changing into Republican ones and vice versa. With a matter of hours before the election, he said “a blanket of anxiety” had settled on the state.

Becker said that while it’s somewhat unavoidable that discussions of voter suppression have roiled Georgia in the days leading up to the midterms, it’s important to reassure voters that the majority of them won’t have any trouble at the polls, which he argues remains true in Georgia.

“If you tell voters they’re going to have to get into a fight with a poll worker or there’s going to be a long line of people getting mad at them because they have to get a provisional ballot, who wants that?” Becker continued. “You want to share the accurate message that almost every voter even in Georgia is still likely to have an easy experience and that their votes are going to count.”

Other canvassers said they’d encountered little if any worry over voter disenfranchisement.

“You know, it’s funny that it’s all you hear about on CNN and MSNBC, but nobody raised it across the hundreds of doors my friends and I knocked the last two to three days,” Erika Soto Lamb, the former chief communications officer of Everytown for Gun Safety, told me by email Monday night. She’d been out canvassing for Lucy McBath, the Democratic candidate in Georgia’s 6th congressional district race.

Muthoni Wambu Kraal, the vice president of national outreach and training at EMILY’s List, had also been door knocking for McBath, and said more often she encountered voters who didn’t know where their polling station was or hadn’t planned on voting because they believed it would be closed by the time they got off of work. She told me it was the job of canvassers like her to provide voters with information and help them develop a plan to get to the polls.

“Days like this still matter,” Kraal said Monday afternoon. “The clouds are ominous, it’s starting to drizzle, but we’re knocking on doors and talking to people who still need to be spoken to.”

By 10 AM Tuesday morning, 10,700 people had already voted in Fulton County, a county in Georgia’s 6th congressional district, according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. An election official told the outlet that there had been some mechanical problems, but said they’d been “quickly resolved.” Such wasn’t the case in Snellville, a suburb of Atlanta, where broken machines reportedly kept voters waiting for more than four hours to cast their ballots.

Long lines had been a problem for early voting as well, Zeigler told me, largely a product of voter turnout increasing by more than 400 percent among voters ages 18 to 30 alone.

“It’s like waiting on line at Six Flags,” a voter in line at an elementary school in the 7th congressional district told an AJC reporter.

These high numbers bode well for progressives. Democrats’ strongest line of defense against Republicans in a red state like Georgia is voter turnout, and with candidates like McBath and Abrams locked in tight races with their opponents, every vote counts.

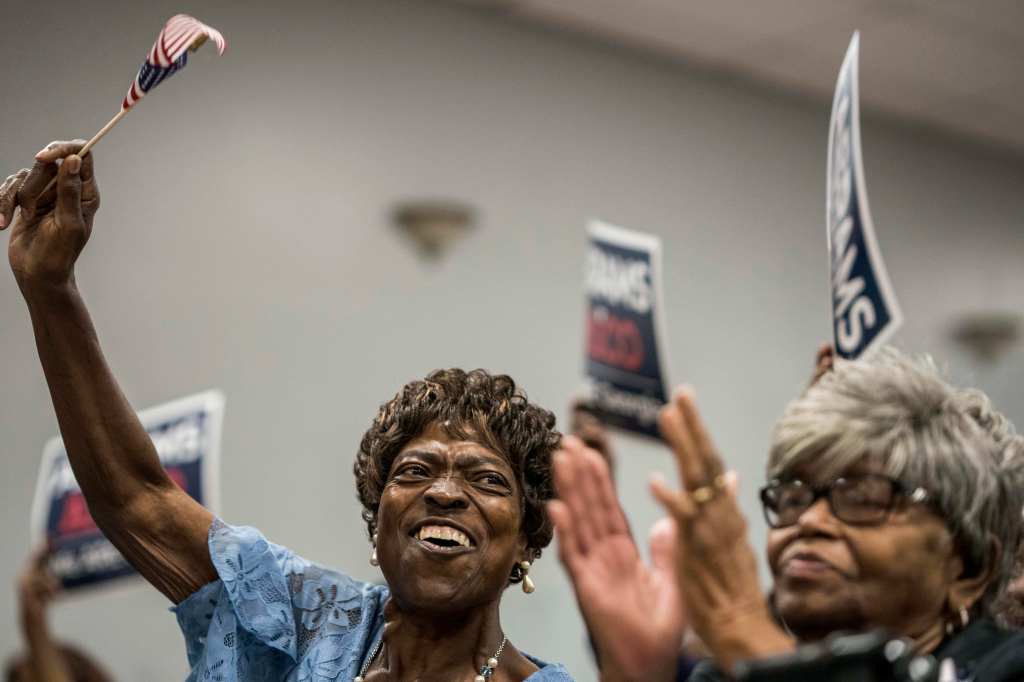

“If we all go out there and vote, he loses,” Riggs Amico said of Kemp, to cheers from the crowd at Sunday’s rally. “What do y’all think about that?”