Franchon Whiting was tired. It was late morning, and she had just gotten off a night shift, hardly sleeping two hours before she woke up to look after five of her six children, all of whom sleep on beds in the den of their apartment. There were two school-age girls playing with their mother’s phone, and twins who were just over a year old, one hooked to a feeding tube in his playpen because developmental delays made him unable to chew his food. A three-year-old boy snoozed on a battered sofa. Whiting’s sixth child, a teenage girl, was at school.

Whiting’s eight-year-old daughter clung to her arm as she opened the door to let Amy de la Fuente into her home. De la Fuente, an organizer with the Metropolitan Tenants Organization in Chicago, was a welcome guest: both of the twins had tested high for lead in their blood after being exposed through the apartment’s chipping paint. She had come to help Whiting find safer housing after Whiting’s landlord, a distant cousin, refused to do anything. But Whiting was still sheepish. “Sorry about the mess,” she said, handing her kids some animal crackers.

Videos by VICE

“I’m not here to judge; I’m here to document,” de la Fuente insisted, her shoes covered in cloth booties to avoid tracking contaminants into or out of the home. As she surveyed the crumbling corners, exposed wires, and chipping window sills of the sparse, three-bedroom apartment, it was clear to her that all the children were in danger.

Lead, the heavy metal that’s still present in our water pipes and old paint, affects well over 3,000 communities and 4 million households across the U.S. It’s an open secret, and a systematic poisoning of brains and bodies, holding back entire neighborhoods: lead exposure is linked to cognitive impairment, behavioral issues, and even violence. We are still learning the lasting impacts of the infamous Flint, Michigan crisis, in which a negligent change in infrastructure led to toxic water and illness. Writer Ta-Nehisi Coates mentions lead in his work about mass incarcerations. But lead poisoning is not limited to one demographic.

While generations past might have been living in homes with lead paint, they did not always experience the exposure that current generations do, because paint had not yet been disturbed by deterioration or renovation. Those who grew up in these homes—built in the mid-20th century, fixed up in the decades after that—are most at risk, especially if they’re poor.

The U.S. federal government, meanwhile, has avoided a key step in protecting people from lead poisoning: regulating landlords. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s standard rule, the Lead Renovation, Repair, and Painting Program, requires that contractors, builders, and construction companies use lead-safe practices. But existing landlords have very little incentive, or requirement, to make sure their property is safe from lead beyond a visual inspection, unless a child in the rental tests positive for the metal in their blood.

This reactive policy means that property owners are often devoid of any responsibility until it’s too late. And so the U.S. remains stuck in a reactive cycle, leaving millions of children vulnerable to lead poisoning. That means the federal government is allowing children’s brains to go underdeveloped, or their bodies to remain sick, unless states scramble to pick up the slack.

*

Whiting moved into the apartment four years ago. The single mother thought the unit, on a quietish street in North Lawndale, Chicago, was in decent shape at the time. But the apartment deteriorated, and her landlord didn’t fix windows when they jammed or repair fraying electrical wiring. When a routine medical exam for the twins revealed high levels of lead in their blood, the landlord hired a handyman without a lead abatement license to paint over the existing lead paint, and then sent Whiting a 30-day notice to move out, likely, according to de la Fuente, so the landlord wouldn’t be responsible for the lead issues.

The stress and uncertainty left the Whitings in limbo. The kids weren’t all in school, because Whiting didn’t want to keep moving them to different school districts if their home changed. She used her food stamps to buy iron-rich foods that the doctor said could combat some of the lead poisoning effects in her children.

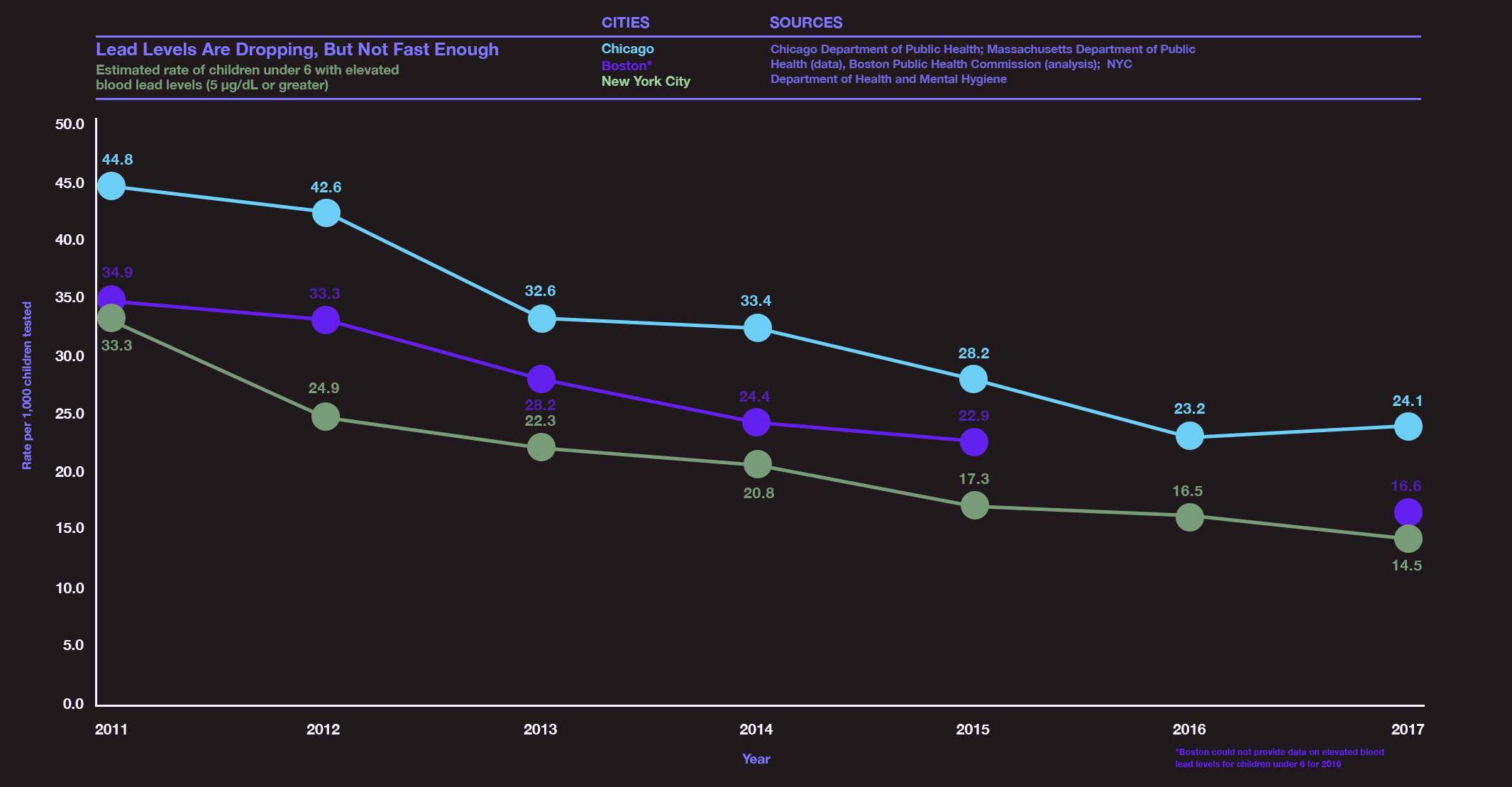

Months later, in October, Whiting would find out that all of her six children had elevated levels of lead in their blood, which could have caused the various developmental delays and health issues they were experiencing. They were now among the thousands of children in Illinois with at least five micrograms per deciliter of lead in their blood, which the Center for Disease Control considers the threshold for unhealthy levels of lead—although the World Health Organization says no amount of lead in the bloodstream is safe.

Chicago ranks high on the list of toxic cities in the country. While lead abatement is relatively straightforward, it is expensive. The city has made several successful pushes to expand universal screening of children, and proactively find affected homes, but these efforts don’t always reach private homes. “On the private side we’ve not had major changes,” said Alison Arwady, the chief medical officer for Chicago’s department of public health. “There needs to be more disclosure.”

In a city where public health department lead inspections are regularly stalled, and former Mayor Rahm Emanuel refused to acknowledge the scope of the problem, that can mean many children slip through screening and prevention attempts. “The mayor has clearly not made this a priority. There’s a lot of old painted wooden structures in the city,” said David Jacobs, a researcher at the University of Illinois, Chicago who helped design some of the federal government’s regulations.

“We don’t have a national or local plan. Those plans should be developed.”

*

Illinois Senator Tammy Duckworth re-introduced two pieces of legislation regarding lead in July itself. She said that while private landlords and property owners are responsible for a large part of our lead issues, cities also need to receive federal funds to be able to tackle the lead in their water sources. “It’s about renters and private owners, but also municipalities being able to replace their ancient lead pipelines,” she said. Only a few states have managed to do that, and not without strong advocacy efforts.

Massachusetts boasts some of the best public health interventions in the country. In 2017, public health activists in the state pushed through a relatively comprehensive lead law. Under this law, the state requires mandatory lead screening for children. Massachusetts also offers interest-free loans to homeowners to pay for lead abatement, and maps out lead issues so that renters and potential buyers can check on the status of their own homes. The state is currently replacing the cities’ underground lead pipes.

Sitting at her usual table in a diner, nestled in the quickly gentrifying Boston neighborhood of Dorchester, Davida Andelman, a public health advocate and leading lead activist, said the fight for safe homes isn’t over. While the state has invested in screening and lead abatement, there is still no requirement for landlords to inspect their homes prior to tenants moving in. “There’s a way around it—property owners get away with discretion,” or turning away families who could threaten them, Andelman said. Because some of the oldest houses in the country are here, it can be particularly difficult to rein in the private sector.

These loopholes can prove dangerous, giving landlords the ability to oust their tenants to avoid the responsibility of ridding their homes of lead. Representatives of the state’s attorney general’s office offered two examples.

In one case, Kirsis Acevedo moved into a Boston apartment with her husband while she was in the early stages of her pregnancy. A few months into living in their new home, when Acevedo was more visibly pregnant, the couple received a notice from the landlord. “Tenant is an expecting mother and apartment is not de-leaded,” said a note from the landlord, meaning the apartment’s paint and water had not been treated or cleaned up. “Please be informed you have up to March 31 to vacate the unit.”

In another case, the Richards family had moved into their home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, with their young children. But the landlords never provided the requisite documents saying whether or not they had tested the home for lead.

Both families were able to take successful legal action against their landlords, reaching financial settlements and forcing lead abatement processes. But not everyone can sue, especially in states with laxer lead laws—and not everyone will win.

*

In 2010, New York resident Tiesha Jones took her four-year-old daughter Dakota in for an annual check-up. Since Jones was switching doctors, the clinic did a full blood workup, including a lead test. The test came back with bad news: Dakota had 45 micrograms of lead per liter in her blood, which is considered on the extreme end of lead poisoning.

Jones said she had already known something was wrong. Dakota, who had been a healthy and normal child, had suddenly changed. “She knew her numbers, her letters, and then she completely forgot all of that,” Jones said.

Jones and her family—at the time she had five children and was pregnant with her sixth—lived in Bailey Houses, a public housing project in the Bronx managed by New York City Housing Authority. Despite receiving the standard housing authority letter that stated her unit had no lead, Jones realized all her children were at risk when they were tested and found to have elevated levels of lead in their blood. She moved them into a homeless shelter the next month. I contacted NYCHA multiple times for comment about the recent lead cases and did not receive an answer.

Lead levels in public housing are actually supposed to be lower than those in private housing, because unlike private homes, public housing projects are managed by both state and federal governments. “I think the evidence is clear on that,” Jacobs said. According to the Housing and Urban Development Agency, apartments with young children are supposed to be inspected every year.

Emily Coffey, a housing justice attorney at the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, said that local housing authorities are required to conduct regular risk assessments and disclose their findings to tenants, unlike private landlords. But these required inspections are not foolproof—many of them are simply visual assessments, wherein inspectors look for chipping paint around windows and doors.

This leaves plenty of room for error. Between 2012 and 2016, New York City found that 820 children living in government subsidized housing had high levels of lead in their blood, prompting public outcry and a widespread audit through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. “The lower-income folks who are unsubsidized are more likely to live in units that are less healthy,” Coffey said.

For Jones, finding out that her daughter was affected led to a lengthy legal battle with the city. It took six months to convince the housing authority to make her housing unit safe, and dozens of blood tests and careful monitoring for Dakota’s lead levels to decrease. “I was angry. You do everything right while you’re pregnant. You take vitamins and you hope the best to have a healthy child. And then something that was out of your reach, something you had no control over, hits you,” Jones said.

Eight years later, in 2018, Jones finally heard back from the city. She received $57 million for the permanent damage caused by the public housing project. These days, she’s studying to go to law school and working on passing Dakota’s Law, a bill to protect children exposed to lead by expanding screening and testing.

*

Tamara Rubin, an advocate and activist, knew her house was a fixer-upper when she moved in with her family in 2002. It was a historic home, more than 90 years old, and registered as such in Portland, Oregon. For one thing, it needed a paint job.

The Rubins had learned about lead in old homes, so they carefully interviewed companies that could do the work without compromising safety. In 2005, they settled on a contractor and checked his references. He soon got to work, using harsh chemicals and tools to blast off existing paint and repaint the exterior of the home.

Then came the signs. The Rubin kids were sick with flu-like symptoms that went on for weeks, and doctors couldn’t figure out why. After three months of watching her middle son, AJ, who was three at the time, vomit and suffer every day, Rubin asked her pediatrician to run every test they hadn’t thought of.

Her two youngest sons (the youngest not quite ten months old) had elevated blood lead levels. The Rubins immediately moved out of the house and started a complex legal process seek compensation for the damages. But the impact on the family was permanent.

“Avi has a brain injury consistent with lead exposure,” Rubin told me. At 14, he has trouble reading and with visual memory. He goes to school part time and is homeschooled the rest. Her other son, AJ, has sensory processing issues and dyslexia, which can be associated with lead exposure.

Remodeling historic houses has become popular among middle- and upper-income families, whether in gentrifying neighborhoods or working class homes. But this trend has several implications where lead poisoning is concerned. For one, lower-income families are often displaced as neighborhoods get more expensive, and are pushed to even more toxic neighborhoods. There’s also a higher risk that the families moving in are exposed.

“There’s a phenomenon that we call ‘yuppie liquid’,” said Jacobs. “These families, they come into poor neighborhoods, rehabilitate a house, and then their children are exposed as well.”

But it’s hard to know who is accountable when there are no consistent policies requiring building or homeowners to maintain or inspect their homes when selling or renting them. That obscurity has led Rubin to take her personal story public. She has a blog called Lead Safe Mama and has spoken at EPA hearings. She helps other parents figure out who to call if they have lead in their home.

“We’re not testing the middle- and high-income level families,” Rubin said. “And that’s dumb: it’s an everyone problem, not just a low-income one.”

Construction and development can also make lead exposure even worse, because pipelines can be rerouted and lead-laden dust ubiquitous. The City of Chicago recently faced a class-action lawsuit in which an apartment building’s tenants said they were experiencing medical difficulties because of the lead in their water, caused by nearby construction. “We were trying to hold the city liable for negligence and get monitoring for tenants and homeowners,” said Beth Fegan, an attorney who represented the tenants in the class-action lawsuit.

While the lawsuit was dropped, Fegan said she and her colleagues are now working to convince the appellate court to recognize medical monitoring, in which groups of people (such as tenants) track their symptoms to pinpoint the source of disease or contamination.

“The city has hidden this particular risk for a long time,” Fegan said.

*

If there’s a common thread among the victims of lead poisoning, it’s that most of their cases are caught by physicians, either in a routine screening or after they’re already showing symptoms. So the medical establishment continues to fight in the corridors of power: Sean Palfrey, a pediatrician at Boston Medical Center and director of the Boston Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, testified in front of Congress on behalf of lead victims after the situation in Flint, where children had been plagued with high levels of lead in their blood even before the water crisis in 2014.

Palfrey said that Massachusetts has made more headway than other states because of its public health community. “The state attracts doctors, health advocates,” he said. “We’ve brought this issue to the forefront of the public.” For the children already affected by lead poisoning, Palfrey said parents are guided to clinics and early childhood programs such as Head Start, which helps counteract the cognitive issues that lead poses through activities and games.

Other cities and states have also been looking for solutions beyond the federal standards. In Madison, Wisconsin, city officials replaced lead pipes proactively, and in Rochester, New York, the city has started inspecting rental homes, instead of waiting for children’s blood tests to reveal lead poisoning, or for landlords to act on their own.

“There are cities that have been taken it upon themselves to pay for the costs [of lead abatement] themselves,” Fegan said. “I think if more of them did, then definitely the burden would shift.”

In Boston, that is already becoming a reality. The Department of Health holds workshops for landlords to learn about funding lead abatement and disclosing their lead policy to tenants. In Chicago, projects such as CLEAR WIN, a program to treat and clean lead-laced windows in older homes, have made significant impact. “I do think we’ve made a lot of progress,” said Anita Weinberg, a professor at Loyola University who worked with the program. “But there’s so much more to do, and the success of our cities depends on it.”

The physicians and advocates also know that leaving lead in the public health realm doesn’t solve the problem. Many landlords only test for lead when it’s too late, and there’s only so much that can be done without a federal mandate. Last December, the Trump administration announced its new, delayed strategy for curbing lead exposure, which included suggestions for the EPA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The framework, like most policy suggestions, was devoid of any actual regulation.

Duckworth said the onus still falls on the EPA, which has stalled efforts to implement more regulations such as the Lead and Copper Rule, which would safeguard drinking water. But under the Trump administration, she said this only seems less likely to happen. “I’m worried they will weaken the rule,” she said. “And we have thousands of communities that are in the same situation as Flint.”

*

It was a beautiful late-summer day when I visited Whiting’s home, but inside it was hard to breathe. The kids coughed, the dust swirled, the TV droned some kind of cartoon.

“You don’t deserve to live like this,” de la Fuente told Whiting in her living room before she left for the day. “You should know that.” She handed Whiting some pamphlets, promising to follow up and help find her a new home. The coming months would mean lawyers, blood tests, calls to the city, and eventually, another temporary home.

For de la Fuente, this problem has a solution. Unlike childhood obesity or even smoking, lead is a public health threat that can be phased out—with funding and education—in just a few years. And if Whiting moved out of this house, her children could actually have a chance.

But for the moment, Whiting only had enough energy to half-smile in resignation, holding one of the twins to her chest. She didn’t say a word.

Data research and analysis by Natasha Grzincic and Nick Perez