The second stage of the Nintendo Entertainment System’s long lifespan started in earnest on April 3, 1997.

By that time, Nintendo had already moved on to 3D gaming with Super Mario 64. But an army of game fans, largely teens and college students who had been young children when the NES first came out in the early 1980s, were setting the stage for its legacy.

Videos by VICE

One of those fans, a programmer from Kansas with an offbeat sense of humor and an unmissable skillset, released a PC emulator for the NES—a reverse-engineered software version of the hardware platform. Called “NESticle,” its Windows icon was, quite literally and indelicately, a pair of testicles.

NESticle, nonetheless, did something amazing: It allowed people to play old Nintendo games on cheap computers made by Packard Bell and other firms, and did so while introducing a number of fundamental new ways to appreciate those games. Divorced from Nintendo’s famously draconian licensing strategy, it introduced new ways of thinking about well-tread video games.

Would we have the retro-friendly gaming culture that we do today without its existence? Maybe, but it’s possible it might not be quite so vibrant.

This is the story of how NESticle helped turn retro gaming into a modern cultural force.

Icer Addis was named Wichita High School Southeast’s Class of 1994 most likely graduate to become a millionaire. He had shown some early signs of brilliance by making PC games with his friend Ethan Petty. By the time he graduated from high school, their company, Bloodlust Software, was riding a wave of success during the shareware era. Their first hit, Executioners, a crude-but-funny beat-’em-up game in the Final Fight mold, was full of visual jokes, some of them featuring Addis and Petty, the game’s visual artist.

“I’m going to say beer and women killed the original Bloodlust Software.”

Its follow-up, Nogginknockers, a bloody, in-joke-fueled take on Pong, came out a year later, and despite the claim that it was a “pathetic attempt to tide people over until our next decent game,” it was still fun. That said, their next decent game, the blood-soaked fighter Timeslaughter, made the case for the increasing sophistication of the two budding game designers, even as the graphics remained somewhat crude.

In an email interview, Petty recalled that Bloodlust’s games were something of an over-the-top response to the culture wars of the time.

“I’d call it an equal mix of Troma movies, professional wrestling, and GWAR. We celebrated the best of the worst in American culture because we thought it was hilarious and found the overreactions to it, especially the religious ones, were even funnier,” Petty said. “We wanted to shock with excessive gore and offensive material just like our idols, but the end result was a lot more crude—you saw it through the lens of high school students trying to be rebels.”

Bloodlust Software’s Nogginknockers. Image: Internet Archive

Petty notes that while he was very much “a 16-year-old with no real artistic training and Deluxe Paint 2, drawing with a mouse,” but his crude style was distinct—you knew a Bloodlust product when you saw it. Addis, with his knowledge of assembly language and C++, helped turn their games into reality.

It wasn’t a partnership built to last, however. Petty and Addis drifted apart as they grew older.

“I’m going to say beer and women killed the original Bloodlust Software,” Petty recalled. “I remember he had a girlfriend who didn’t like me too much and I was spending a lot of time playing drunken Dungeons & Dragons with a crowd of Kansan misfits (don’t judge). Eventually, I dropped out of college and moved to New York, chasing an IRC girlfriend (don’t judge!), which was probably the nail in the coffin.” (Addis could not be reached for this article.)

While the Bloodlust partnership eventually faded away (with a partly-completed Contra-style game left for dead), the name didn’t—and neither did its distinctive style.

As the partnership that spawned Bloodlust was fading from view, another world was starting to grow in stature—the subculture of retro gaming.

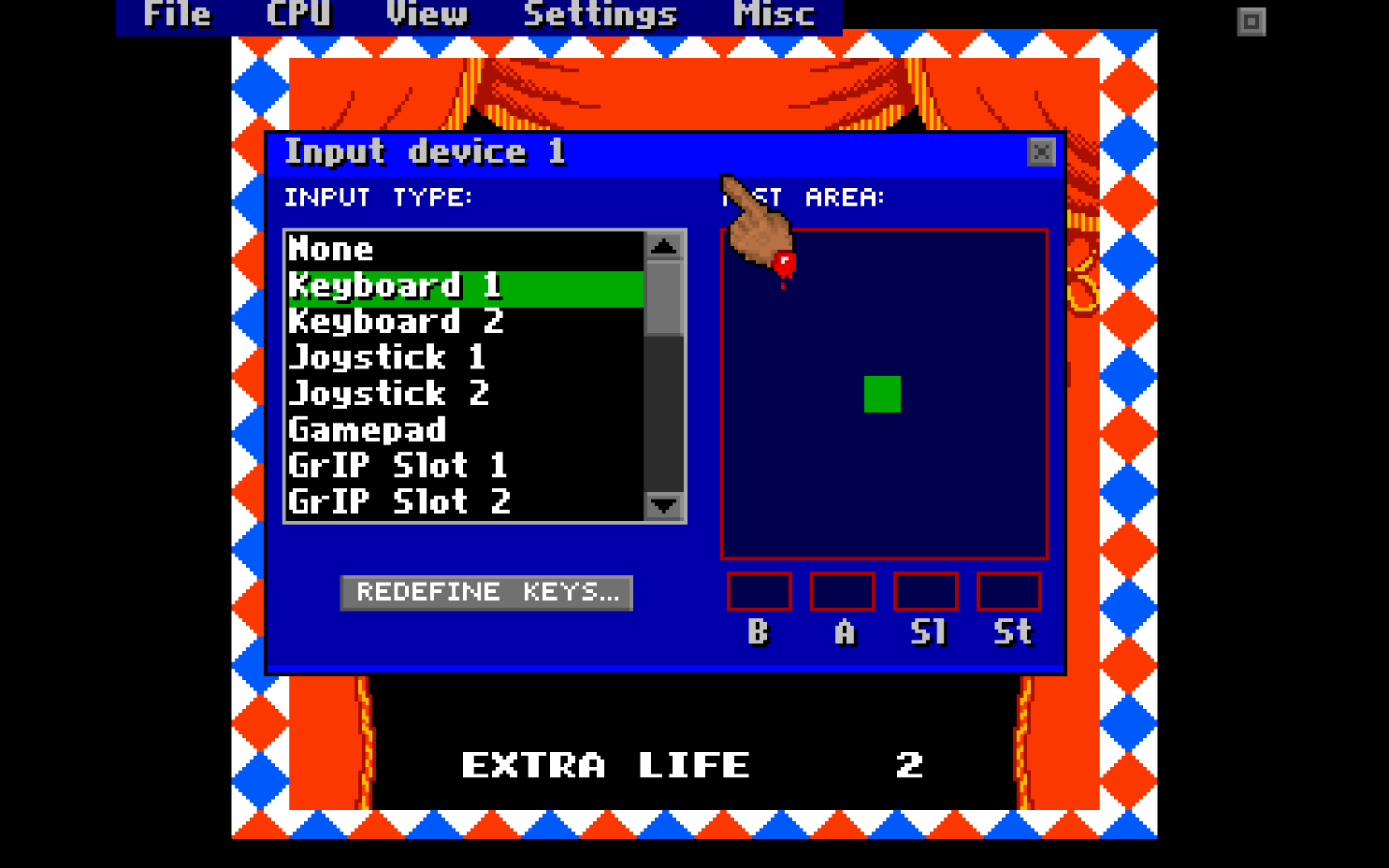

Nesticle interface

Before console emulators became common in the late 1990s, a lot of work had to be put into understanding how outdated systems worked. Collectives of folks who grew up with these games used their budding technical skills to reverse engineer the devices, sharing knowledge with their peers in text files, on slapdash websites, or within FTP servers.

In a 1996 interview with the DOS-based diskmag Affinity, Donald Moore, a scene figure who initially was known only by the handle MindRape, described the appeal of the console scene at the time, which he compared to the hacker mindset of the Commodore 64 scene, rather than the piracy-minded Warez scene that predated the file-sharing era. (The leaders of that scene got in trouble.)

Moore’s group, Damaged Cybernetics (DC), focused instead on “gray area” topics like cartridge-dumping and CD-ripping—which were considered somewhat lighter shades of piracy at the time. In his comments to Affinity, he emphasized that messing around with consoles differed sharply from distributing copies of shrink-wrapped Windows software.

“The truth is this: Consoles are much more fun than the PC Warez scene and other scenes,” Moore explained.

But the truth was more complicated. Moore recruited Jeremy Chadwick, an early figure in the NES and Super NES emulation scenes who was responsible for some of that early digging, to be a part of his group. Chadwick characterized his role in the group as something of a moderating influence on Moore, the latter of whom became known (after the fact) for a slogan: “Information wants to be free!”

“I had some ethical and moral qualms with some of Don’s views,” Chadwick recalled. “I didn’t want to be involved with anything that posed the risk of going to jail or having to deal with law enforcement. After some back-and-forth, he accepted, so I joined up with effectively a gentleman’s agreement applied.”

Legal problems were a legitimate concern. As MindRape, Moore had gained early notice in the legendary hacking zine Prhack, which reported on a 1991 FBI raid on his home without producing his full name. The reason? An online newsletter he had created called National Security Anarchists, which shared the kind of hacking-related info that Phrack did.

Image: Chris Kindred/Motherboard

After that incident, Moore never really tried to hide himself from the spotlight again. He often used his real name in interviews in tandem with his username, meaning that when he had uncovered an early technique for analyzing Microsoft’s CD-Key validation design, he was credited for the find under his real name.

The early culture around video game emulation—driven by Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels—could be all-consuming at times. Brad Levicoff (a.k.a. Zophar), the creator of the popular emulation news site Zophar’s Domain (full disclosure, a site I worked on during my teen years) recalled that maintaining his large repository of emulators and console-related information required a large amount of time and research.

Despite being the site’s namesake, he eventually outgrew it, handing it off to others. It remains active to this day.

“It was an enormous responsibility for a teenager and became my entire world to the exclusion of everything else,” he explained. “When I made the decision to leave, it was one I spent a considerable amount of time making and I didn’t take it lightly.”

In the midst of all this, Icer Addis was putting the finishing touches on NESticle, an emulator that benefited from Addis’ years of making fighting games. Programmed in assembly code and C++, it was blazing fast and very easy to use.

And when it was released into the wild, it was like a bomb dropped onto a modest scene of console hackers. Suddenly, it seemed like everyone with a home computer and fond memories of Zelda was interested in what this little scene was doing.

“Perhaps the most important thing the emulator did, according to Altice, was that it democratized the process of modifying a game.”

And that underground culture buckled under the sudden attention.

NESticle was not formed in a bubble. It benefited from the work and technical resources of Damaged Cybernetics and other scene groups, as well as the failings of prior emulators, such as the Japanese emulator Pasofami as well as iNES, an emulator created by the developer Marat Fayzullin.

Pasofami initially relied on a split-format ROM that was complicated to use. And while Fayzullin’s iNES improved on this by creating the now-standard .nes format, his decision to charge for his emulator—and mark his emulator with a particularly annoying, hard-to-ignore nag screen—rubbed some the wrong way and limited its initial success outside of the Macintosh platform.

(Nonetheless, Fayzullin’s work proved very influential. Addis specifically credited Fayzullin’s research into the inner-workings of the NES in the FAQ for NESticle.)

NESticle got around the problems of its competitors by being fast, easy to use, and free—though not open-source. It focused on usability over accuracy, which turned out to be a bit of a breakthrough for emulation of the time. The emulator was almost entirely the work of Addis, though it had Bloodlust branding and visuals. Petty played a very tiny (but noticeable) role in the emulator’s creation—he drew the famed bloody hand that was the program’s mouse cursor, along with Shitman, a character from the discarded Contra-style game, showing up in the emulator’s “About” menu.

“I think rather than setting out to make Bloodlust emulators, he simply used the ‘brand’ he had already established,” Petty explained. “I’m happy he did—those emulators allowed people to re-experience many of the games that inspired Bloodlust.”

The emulator’s style has always been something of a trademark—for some, even a deterrent, just like the look of the Bloodlust’s games. But the emulator’s success was hard to ignore.

In the 2015 book I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform, author Nathan Altice spent a significant amount of time highlighting the role of NESticle, which he argued was highly influential due to its numerous additional features.

“NESticle was not the first NES emulator, but it introduced or popularized a number of now standard augmentations like save states, simple tile editing, and movie recording,” Altice explained.

Perhaps the most important thing the emulator did, according to Altice, was that it democratized the process of modifying a game, making it something a person with relatively limited skill could pick up without a lot of trouble, and with more sophistication than, say, a Game Genie. It was a significant upgrade from what prior emulators could do. Per Altice:

The user modifications NESticle afforded were a new phenomenon for console owners. Few had the resources or know-how to dump, edit, and burn custom EPROMs. A handful of NES games like Excitebike and Wrecking Crew featured built-in level editors, but such tools were uncommon, edits were temporary, and there were no means to share creations with other players. Hardware cheat devices like the Game Genie only permitted users to tweak existing game parameters, and without knowledge of the peripheral’s underlying code generation algorithm, players were typing codes blindly in hopes of surfacing novel results.

These innovations, over time, created major reverberations in gaming culture. Fan translations of Japanese video games gained currency through emulators like NESticle, along with its counterparts for other consoles like SNES9x. Graphic modifications of games became common. Movie-recording functionality became a fundamental feature that soon inspired speedrunning and modern-day services like Twitch.

But NESticle nearly didn’t live long enough for many of these innovations to make it into the final version. The reason? Simply, the culture of console hackers struggled to handle the sudden, almost unprecedented success of NESticle.

Almost immediately after the emulator’s release, trouble was brewing. Addis’ very fast initial release schedule raised expectations among end users, putting undue pressure on him to release new versions.

Moore, meanwhile, had apparently tired of Addis, who went by Kronk or Sardu on IRC at the time. Discovering that Addis’ machine was accessible through an open file share, Moore broke in, taking the source to NESticle and other materials.

Chadwick (known at the time as Y0SHi) recalled how the ethical concerns that gave him misgivings about originally joining Damaged Cybernetics came to a head once Moore’s theft became clear.

“I recall telling him I thought it was inappropriate and that the ramifications could be severe,” Chadwick explained. “It might cause Icer Addis to stop development of NESticle, for example (and that’s exactly what happened). Icer was rarely seen online at that point, but he was always nice (yet terse). He was a very private person, and there was no reason to violate that.”

Chadwick noted that Moore hadn’t just stolen NESticle, but the source codes of a number of other emulators of the time, including iNES and VeNES—the latter worked on by Josh McKee, Chadwick’s roommate at the time. Chadwick was quick to call out Moore.

“[At] that point, the IRC emulation community had some kind of deep hatred for [iNES developer] Marat; the guy was uncouth, but he didn’t deserve any of that,” Chadwick said.

When others on IRC learned of the source code theft, they pressed Moore to release it. He did—a move that had the dual effect of taking down Damaged Cybernetics and halting NESticle’s development.

Addis blamed both Moore and those who downloaded the code—something that, to this day, Chadwick says he has never looked at.

Nesticle interface

“MindRape knew what he was doing and he was well aware of the repercussions of his actions,” Addis wrote, according to a Usenet retelling of the situation. “Anyone that receives ‘it’ from him I find to blame as well. He handed you the apple and you all took a bite … banished from Eden you are. For those reasons and for the greediness of the general public, I finally have realized that people do not deserve a free emulator such as this.”

In a 2000 interview for the site Kinox, Moore claimed the motive behind the hack was a combination of dissonance and personal issues. Dealing with a messy divorce that involved child custody issues, he had a lot going on at the time. But he also put some of the blame on the folks in the IRC chatroom that day.

“That I really pissed off a lot of fucking ppl,” Moore said. “Which is great, i love jerk’n ppl’s chains. … One important thing I learned from this tho, there are loads and loads of hypocritical pirates or pirates with morals.”

Gingerbread, an information security pro friend of Moore’s who chose not to use his real name for this interview, didn’t know him at the time of the incident, but became close with him years later. He noted that Moore’s tone on this issue shifted some with time. “I think that as time passed, he was more honest with himself, and as a result others, about just what he was thinking all those years ago,” he said.

Addis, eventually, had a change of heart about the discontinuing NESticle, reviving it about a month after the incident. And in the year or so afterwards, he built a small empire of noteworthy emulators, each with a name nearly as gross as NESticle. Genecyst, with its bloody menu, emulated the Sega Genesis. And he further showed off his technical skills with Callus, which emulated a Capcom arcade platform. Callus outmatched even the standard-bearer of the time, a rival emulator called MAME (Multi Arcade Machine Emulator).

But one console that he never did touch at the time was the Super NES. In part, he didn’t have to—unlike the NES, there were ample examples of sophisticated emulators at the time, thanks in part to the reverse-engineering work of folks like Chadwick. If you wanted a Super Mario World fix, SNES9x and its eventual competitor ZSNES could do the trick. But it may have been a lingering side effect of the source code theft: In his note when he originally discontinued NESticle, he noted that “the SNESticle project has been discontinued as well.”

There was of course, strong interest in a Super NES emulator from Addis, but he never took the bait. In an FAQ from the final version of NESticle, released in July of 1998, he puts it bluntly: “Do not ask about SNESticle (or anything else you want emulated).”

Soon after the release of the final versions of NESticle and Genecyst, Addis went dark. His work was eventually superseded by emulators that took advantage of the fact that the end user was probably using something better than a 486-processor.

When media outlets talked about emulation in the 90s, it was almost always in the context of the arcade emulator MAME. But today, the console emulators of 1997—NESticle, Genecyst, SNES9x, and numerous others—perhaps cast the longest shadow on retro gaming. Their success was a turning point, one that really feels all the more impactful separated from the ROM-begging dynamic of the year, a pretty great example of an Eternal September-like situation that Levicoff described in depressing detail in a 1998 article.

Gingerbread noted that the interest in the scene among the more technically minded ended, in part, because of the flood of new people, many without technical backgrounds. “NESticle was a game changer,” he said, “and a game ender.”

These days it’s not about begging for ROMs, fortunately. Important parts of online culture, like the Angry Video Game Nerd, speedrunning, or fan-made game translations? Their lineage starts during the first two weeks of April of 1997, when NESticle made the past the star of the show.

Nintendo itself, despite the interest that emulation created in its vintage products, has often dismissed the practice, but the NES Classic, which included a hidden message for device hackers, was made possible by it. And some games in its Wii Virtual Console used Marat Fayzullin’s now-standard iNES headers.

Fayzullin and many others are still actively producing emulators, but the “emulation scene” of the era—the forums and IRC channels full of teens and college-aged kids, enthralled about playing old games on their new computes—peaked not long after NESticle’s 1997 release.

It was a great moment in time, but people grew up, got jobs, and moved on.

And sadly, we lost some of those people along the way. Donald “MindRape” Moore, an icon of 90s hacker subcultures with a reach far beyond emulators, died last year after battling an illness.

“Aggressive treatment started immediately and Donald gritted his teeth for a long, bumpy ride,” Gingerbread said of his friend. “Unfortunately, while bumpy, the ride was all too brief, and on the 22nd of May 2016, MindRape (Donald Moore), with great reluctance, finally hit the power button…and let the discs spin down.”

Having matured into an elder statesman of sorts, the kind of guy who would show up at DEF CON every year, Moore’s passing led to an outpouring of sadness in some corners of the internet when it was announced last year.

“He’s a genius, and I’m not saying that just to be nice.”

Source code theft aside, he was fundamental to what emulation became—and it’s possible that MP3s might have taken a bit longer to gain mainstream acceptance had Moore and others not built a formative scene around digital music. That bitterness fades over time; scene drama always looks smaller in hindsight.

Brad Levicoff of Zophar’s Domain, whose teenage comments on the matter became an important part of the folklore around this story, notes that Moore’s decision to release the source code to NESticle, whatever the reasoning, had a significant impact on console emulation going forward.

“Although I’m sure he was a nice guy in the real world, I don’t think he had the right to decide for Icer whether or not the source code to NESticle should be public,” Levicoff wrote. “But I do know that many, many more NES emulators were created after this and I’m sure authors were influenced in some way by this code. Once something’s on the internet, it’s out there forever.”

It is out there forever, but the people who create these things eventually move on. And much like emulation eventually became accepted by the broader gaming community—see the sheer excitement around the NES Classic—so, too, did the two guys who spent the 90s creating crude, bloody video games under the name Bloodlust.

Ethan Petty eventually found work with Ubisoft as a designer and scriptwriter, putting his handiwork on a number of hit games, such as Watch Dogs 2 and Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood. On the side, he’s been working on reviving and updating his Bloodlust-era art style for the modern day with his point-and-click style game Knobbly Crook. (It definitely wasn’t made with his tool of choice in the 90s, Deluxe Paint 2.)

And Icer Addis, who is a hard man to track down, has become an important technical force within the gaming industry. For years, he worked with Electronic Arts on a number of the company’s Madden football games, among others.

“He’s a genius, and I’m not saying that just to be nice,” Petty said of his high school friend. “This was a kid programming in C++ and Assembly and pumping out games just as technically complex as the professional studios at the time. I don’t think he needed Bloodlust at all to get where he was going. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if he left it off of his resume.”

More recently, Addis has spent time at Zynga, where his emulation past came in handy. In 2016, Addis and a co-worker were awarded a patent titled “In-browser emulation of multiple technologies to create consistent visualization experience,” and he assisted with creating a cross-platform compiler called PlayScript.

Another game Addis worked on while at Electronic Arts was a boxing game for the GameCube called Fight Night Round 2. He isn’t directly credited for his work on the game, however. Instead, his role with the game involves an unlockable version of Super Punch-Out that’s included on the tiny disc.

Buried in the source files for the game, in a place that’s only possible to find, really, if you’ve extracted the game files using the GameCube and Wii emulator Dolphin and are specifically looking for it, is a telling string of text: “SNESticleNGCVERIONPP71Copyright (c) 1997-2004 Icer Addis”

The long-rumored SNESticle? He had it all along.

*

Ernie Smith is a contributor to Motherboard, and the editor of the twice-weekly newsletter Tedium , which hunts for the end of the long tail. He also spent time working on Zophar’s Domain when he was a teen, which is a really cool thing to note in a bio.