We know you’re busy. You probably haven’t had time to read every article we’ve published on VICE.com, so we’re re-featuring some of our old favorites. This one originally published on October 15, 2014.

In jails and prisons around the world, tattoos can become a significant part of an inmate’s uniform, not only marking the crime they’re in for but also serving as a way to communicate with others. In Russia, for instance, a dagger through the neck suggests that an inmate has murdered someone in prison and is available to carry out hits for others-meaning, if you see that guy walking toward your cell once all the guards have disappeared, you should run the fuck away.

Videos by VICE

Arkady Bronnikov, regarded as Russia’s leading expert on tattoo iconography, recently released a collection of around 180 photographs of criminals locked up in Soviet penal institutes. Russian Criminal Tattoo Police Files, published by FUEL, is probably the largest collection of prison tattoo photographs to date, at 256 pages.

I got in touch with Damon Murray, co-founder of FUEL, to talk about the book.

VICE: Why did you want to publish this book?

Damon Murray: At FUEL, we previously published the Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia series, as well as Drawings from the Gulag and Soviets–so there’s an obvious pattern. These books were based around the drawings of Danzig Baldaev, a prison guard who documented the phenomenon of the Russian criminal tattoo over the course of his career.

It was while researching Soviets that we came across an article about a retired policeman named Arkady Bronnikov. A senior expert in forensics at the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs for more than 30 years, his duties involved visiting correctional institutions in Ural and Siberia. It was then-between the mid 1960s and mid 1980s-that he interviewed, photographed, and gathered information about convicts and their tattoos, building one of the most comprehensive archives to date.

We knew that this collection of unique material would make a fascinating book and be a perfect addition to our previous publications. It tackles the same subject, but in a more visceral manner.

How long did it take you to collect the photos?

I visited Mr. Bronnikov at his home in the Ural region in Russia. We’d previously discussed the possibility of making a book, and he very kindly agreed to talk me through the material and discuss the intricacies of the subject in detail. After a few days, it became apparent that there was enough material and information to make a book that was significant in its own right. I then took the photographs back to London to be scanned.

Do you have any information about the prisoners who were photographed?

Apart from a small section at the very beginning of the book, which reproduces a number of actual police files, all the information gathered about the criminals is done by reading the tattoos on their bodies. Their crimes vary from serious cases such as murder or rape to lesser offenses like pickpocketing and burglary.

Every image carries a detailed caption explaining how individual tattoos relate to specific crimes-for example, a naked woman being burnt on a cross symbolizes a conviction for the murder of a woman. The number of logs on the fire underneath the victim denotes the number of years of the sentence.

What kind of equipment were they using to tattoo themselves?

The majority of the tattoos would have been done in a primitive, painful way. The process can take several years to complete, but a single small figure can be created in four to six hours of uninterrupted work. The instrument of choice is an adapted electric shaver, to which prisoners attach needles and an ampoule of liquid dye.

A dagger through the neck indicates that a criminal has murdered someone in prison and is available to hire for further hits. The drops of blood can signify the number of murders committed.

Where do they find the dye?

Scorched rubber mixed with urine is used for pigment. For health reasons it’s best to use the urine of the person getting the tattoo. Because tattooing is forbidden by the authorities, the practice is pushed underground, and usually executed in unsanitary conditions. This can easily create serious complications, including gangrene and tetanus. But the most common problem is lymphadenitis-an inflammation of the lymph nodes accompanied by fever and chills.

But they do it anyway?

In most cases, the inmates interviewed by Bronnikov claimed that they started getting tattoos only after they had committed a crime. As their convictions increase and the terms of incarceration become more severe, the tattoos multiply. In minimum-security prisons, for example, 65 to 75 percent of the convicts have tattoos; that figure increases to 80 percent in medium-security prisons, and to between 95 and 98 percent in maximum-security facilities. In the female corrective facility near the Perm region-about 700 miles northeast of Moscow-Bronnikov found only 201 out of 962 were tattooed, but as many as 40 percent were tattooed in the high-security prison.

As a rule, criminal leaders don’t have a large number of tattoos-only a pair of seven- or eight-pointed stars on the collarbones. Also, tattoos are reserved for the criminal element, so they aren’t found among prisoners serving sentences for political crimes.

One of many prisoners who contracted syphilis, AIDS, or tetanus while being tattooed in unsanitary conditions

What are your personal views on the culture of prison tattoos?

Well, it’s remarkable-nowhere else do tattoos express such a unique and defined language. Every image is charged with meaning; a tattoo can literally be a matter of life or death for its bearer.

When any new convict enters a cell, he is asked, “Do you stand by your tattoos?” If he can’t answer-or if word reaches the other inmates that he’s wearing a “false” tattoo-then he’ll be given a piece of glass or a brick and be asked to remove it, or face the consequences. That could be a severe beating, rape, or even death.

It’s for this reason that tattoos became the most respected and feared thing in prison society. Far more than being simply personal, they carry a weight of meaning and are an indelible law in a society beyond conventional law.

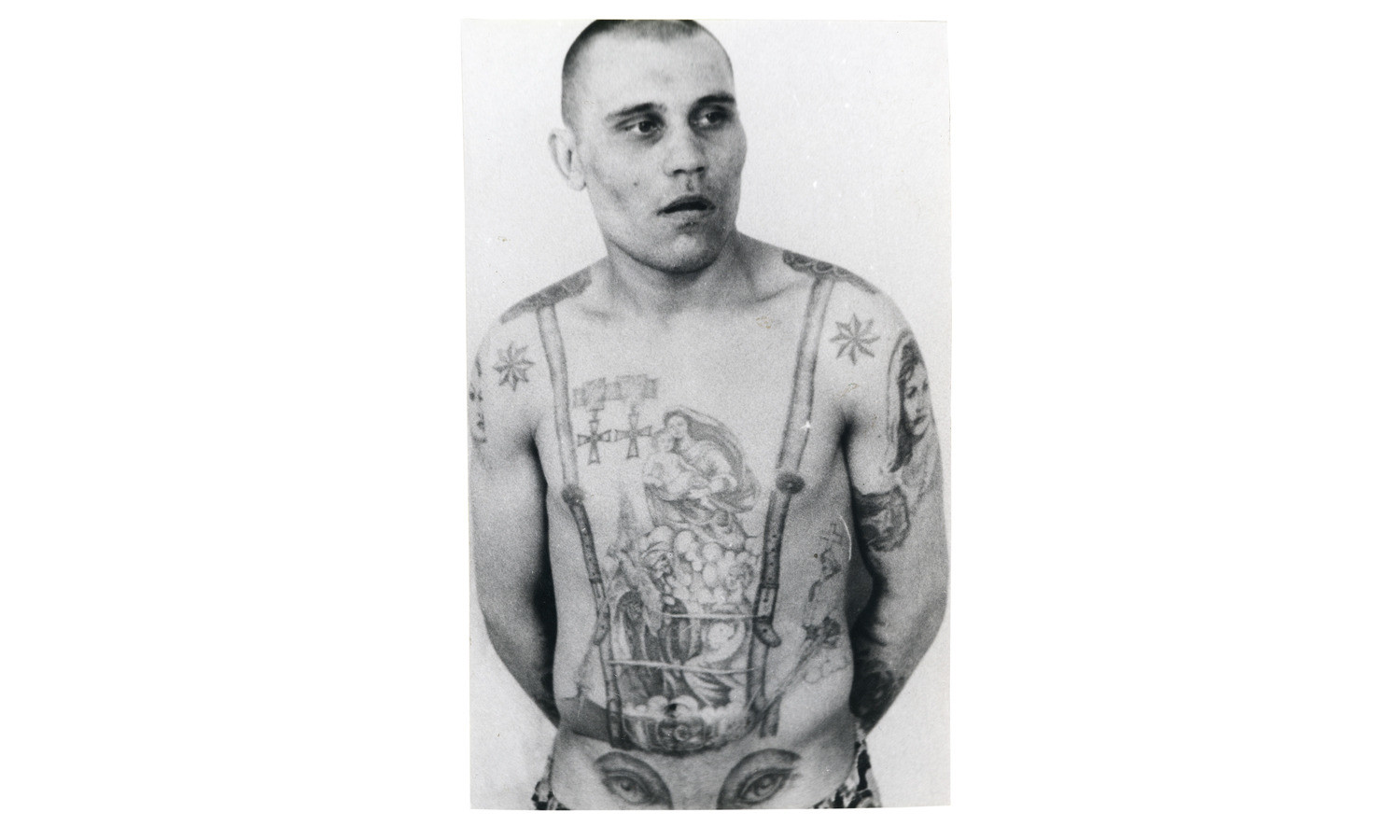

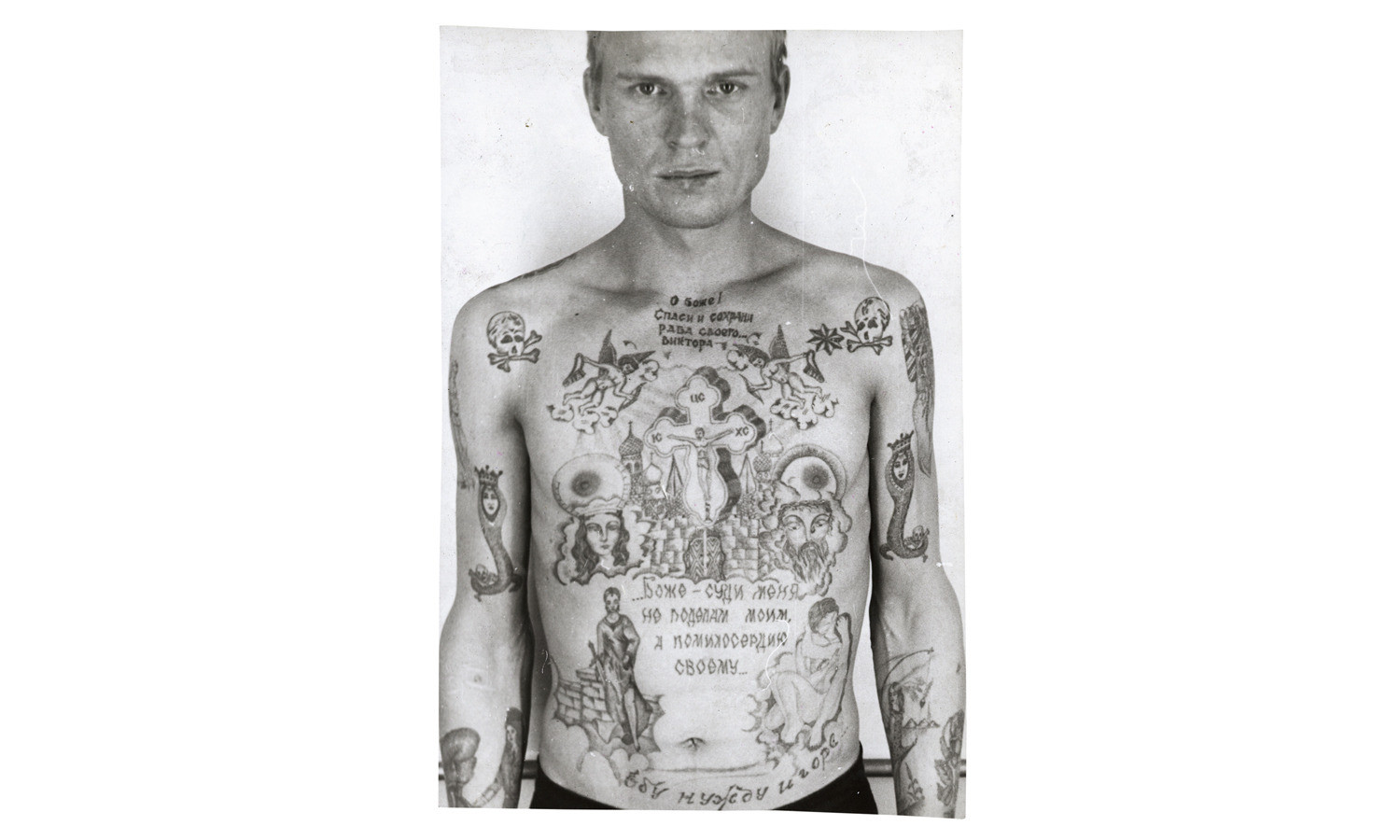

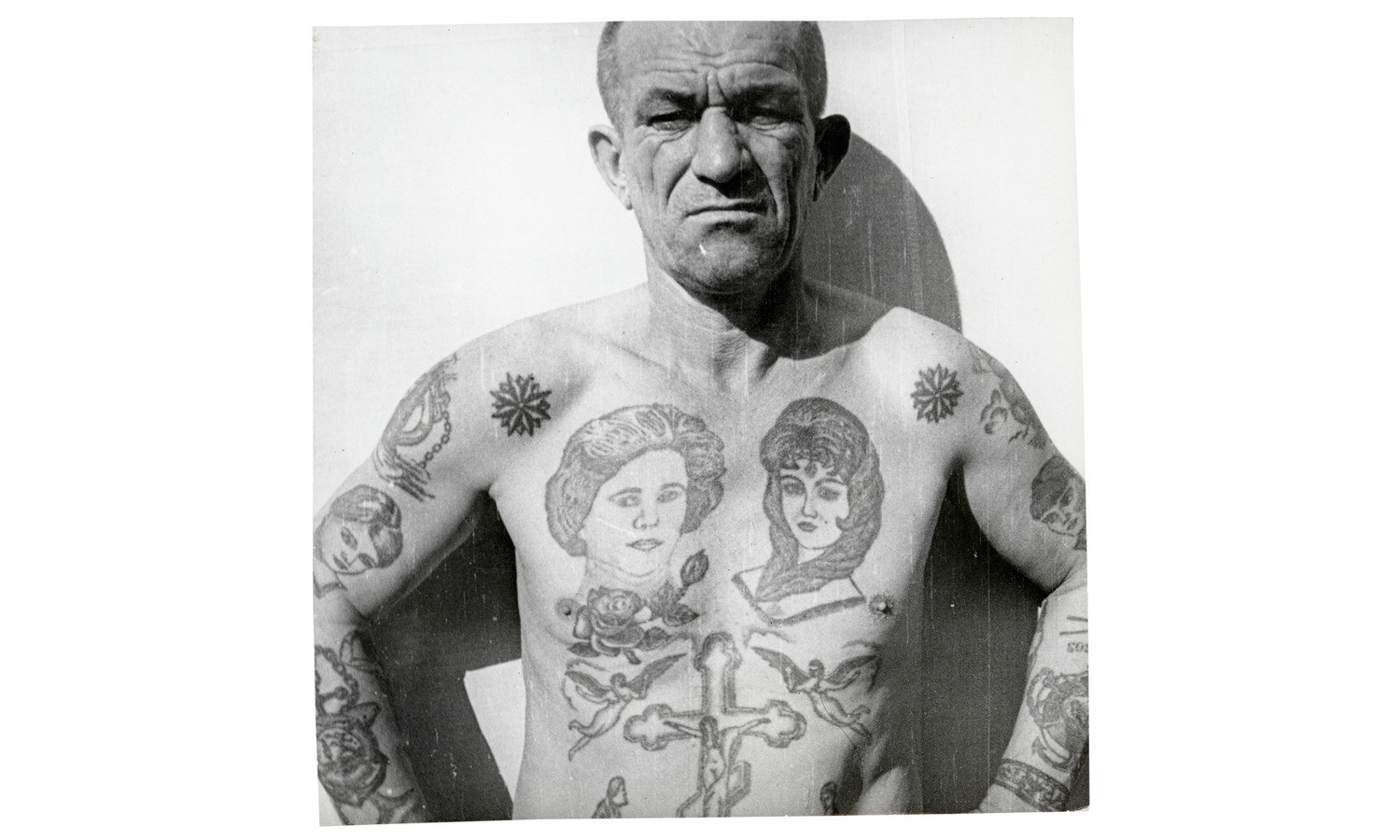

The stars on this inmate’s shoulders indicate that he’s a criminal “authority,” while the medals are awards that represent defiance against the Soviet regime. The eyes on the stomach suggest that he’s gay (the penis makes the “nose” of the face).

You’ve seen plenty of prison tattoos. What were the most common?

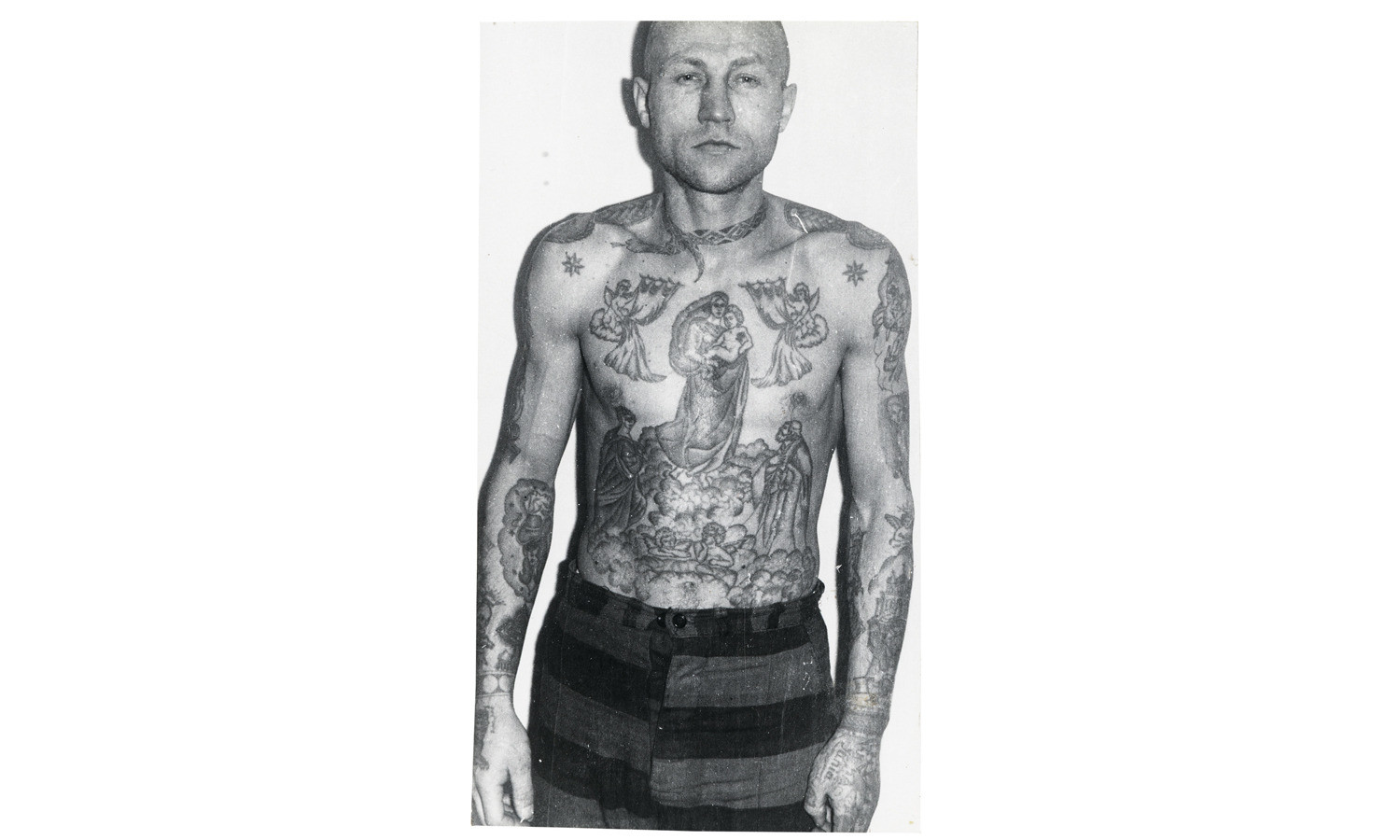

There are many common themes and ideas. Some of the most common imagery is religious: the Madonna and Child, Russian churches, crosses, that kind of thing. However, in the context of the Soviet prison system-or “the zone,” as it’s called-those images have absolutely nothing to do with religious beliefs; their real meanings are rooted in prison and criminal traditions. They stem from the desire to show oneself as an outcast, as someone who has been misunderstood and is doomed to suffer.

The Madonna and Child is one of the most popular tattoos worn by criminals, and it can have a number of meanings. It can symbolize loyalty to a criminal clan, it can mean that the wearer believes the mother of God will ward off evil, it can indicate that the wearer has been in the jail system and behind bars from an early age…

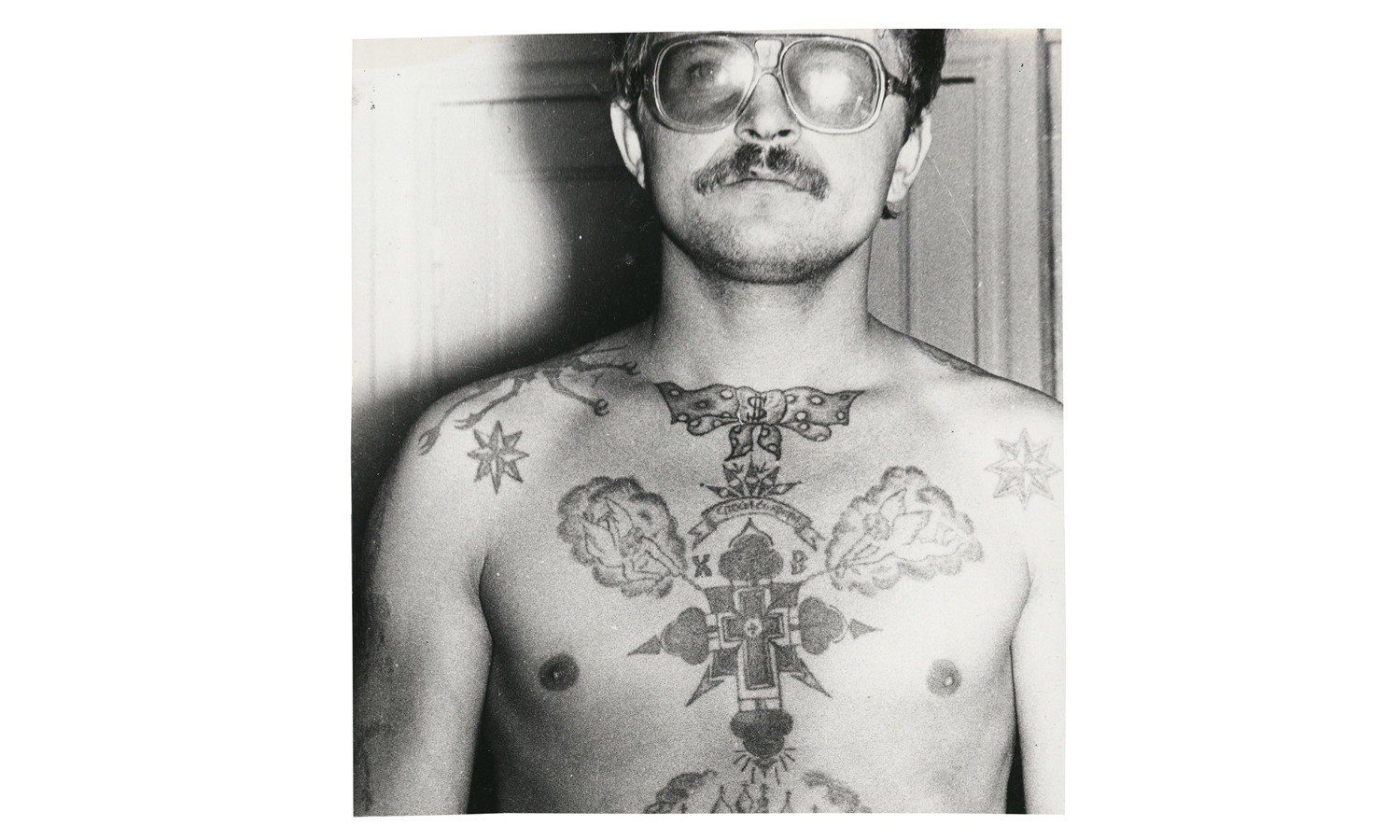

In the zone, a church or monastery is interpreted as the sign of the thief, with the number of cupolas [domes] on the church signifying the number of convictions. A cross is commonly tattooed on the most important part of the body: the chest. This is intended to show a devotion to the thieves’ traditions and stand as proof that his body is not tainted by betrayal-that he is “clean” before his fellow thieves. All crosses indicate the bearer belongs to the caste of thieves.

What was the original purpose of archiving these photos?

The Bronnikov collection featured in the book is particularly interesting, as its purpose was purely functional. The photographs were taken for police use, to further the understanding of the language of these tattoos and to aid the identification process for criminals in the field.

The photographer’s only consideration was the recording of the body for practical purposes. As they’re unimpeded by artistry, the photos present a guileless representation of criminal society, unintentionally leaving out their human side and instead simply including evidence of their character: aggressiveness, vulnerability, melancholy, and conceit. Their bodies display an unofficial history-told not just through tattoos, but also in scars and missing digits.

An exhibition of photographs from the Arkady Bronnikov collection will take place at the Grimaldi Gavin gallery at 27 Albemarle Street, London between October 17 and November 21.

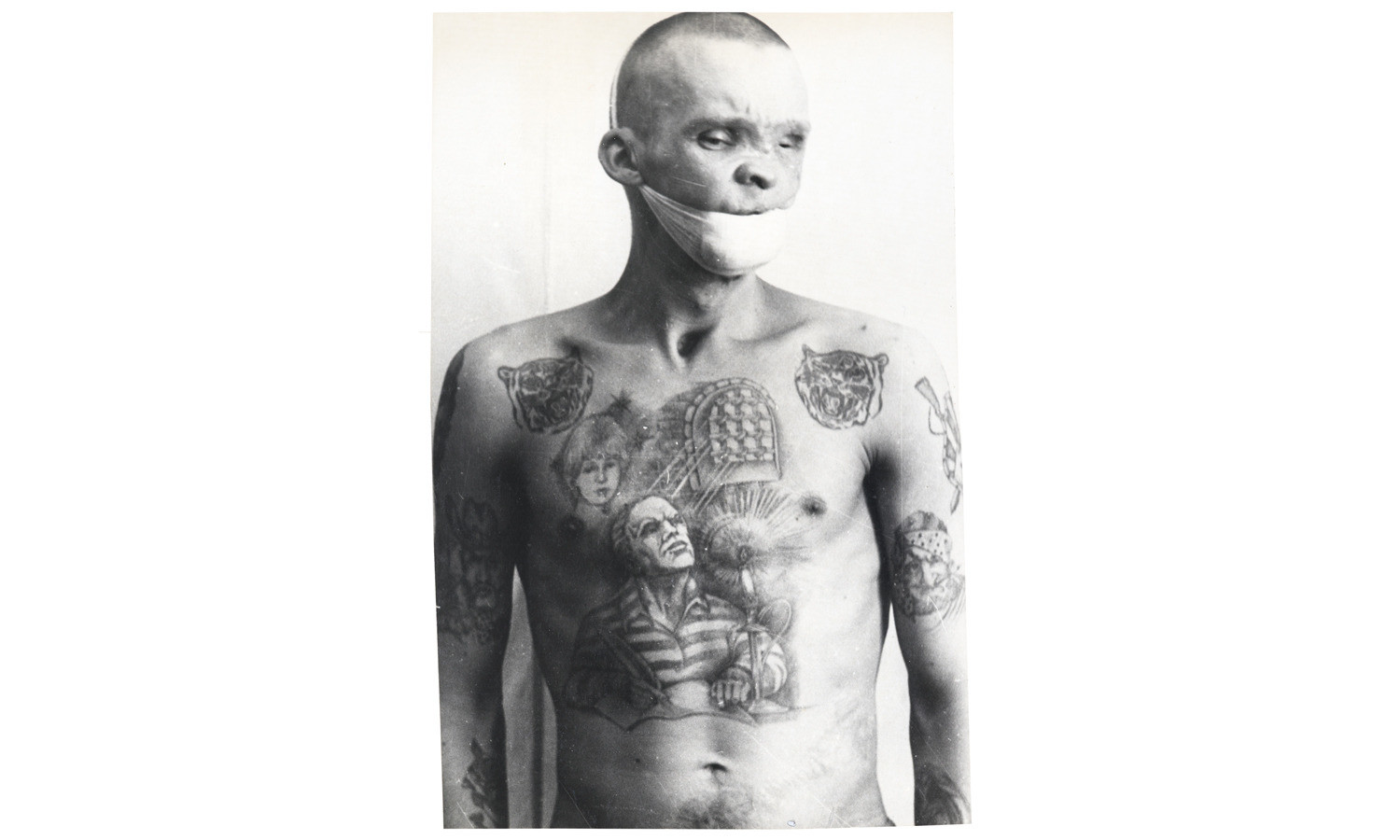

The eight-pointed stars on this inmate’s shoulders indicate that he’s a criminal “authority”, while the medals are awards that represent defiance against the Soviet regime. The eyes on the stomach suggest that he’s gay (the penis makes the nose of the face).

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

A snake around the neck is a sign of drug addiction.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

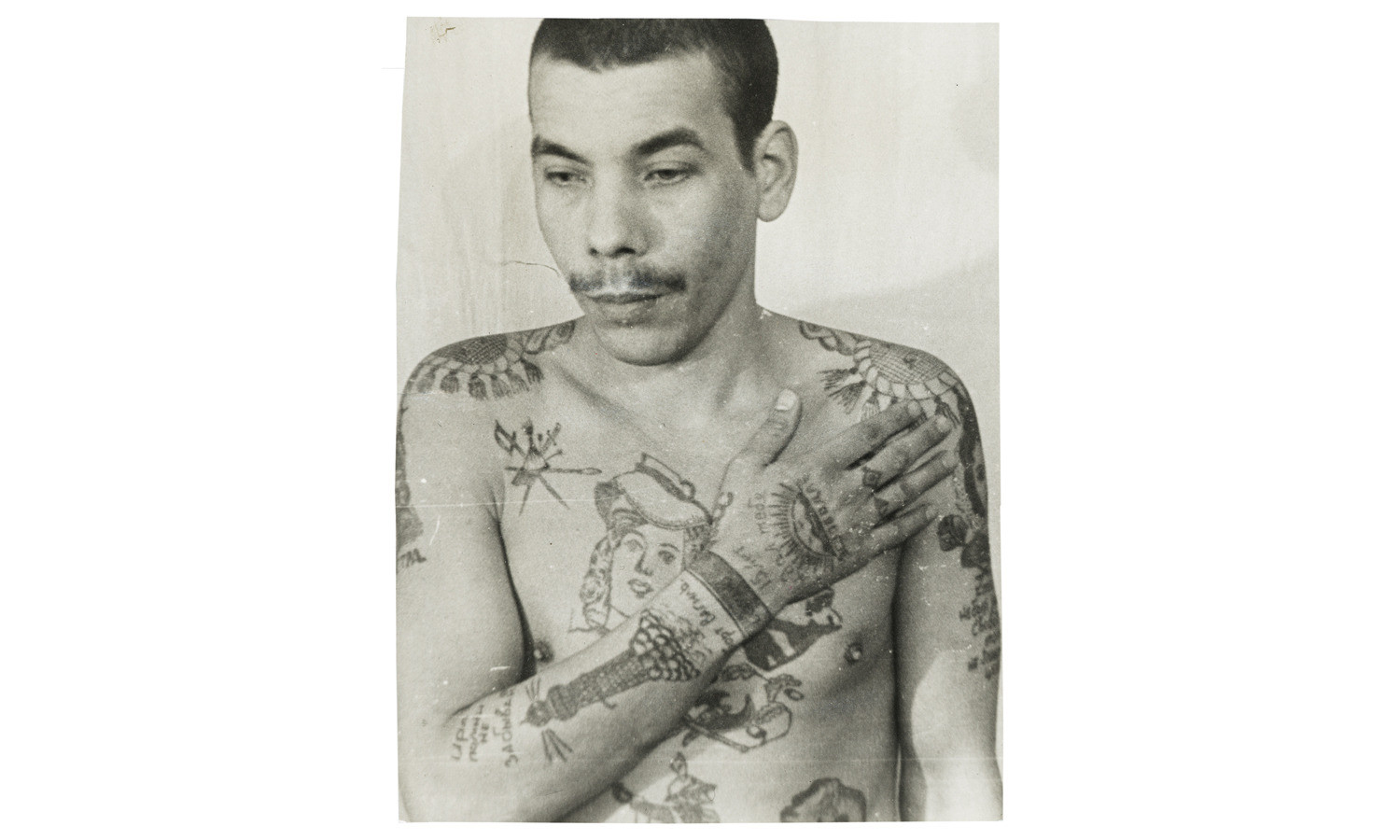

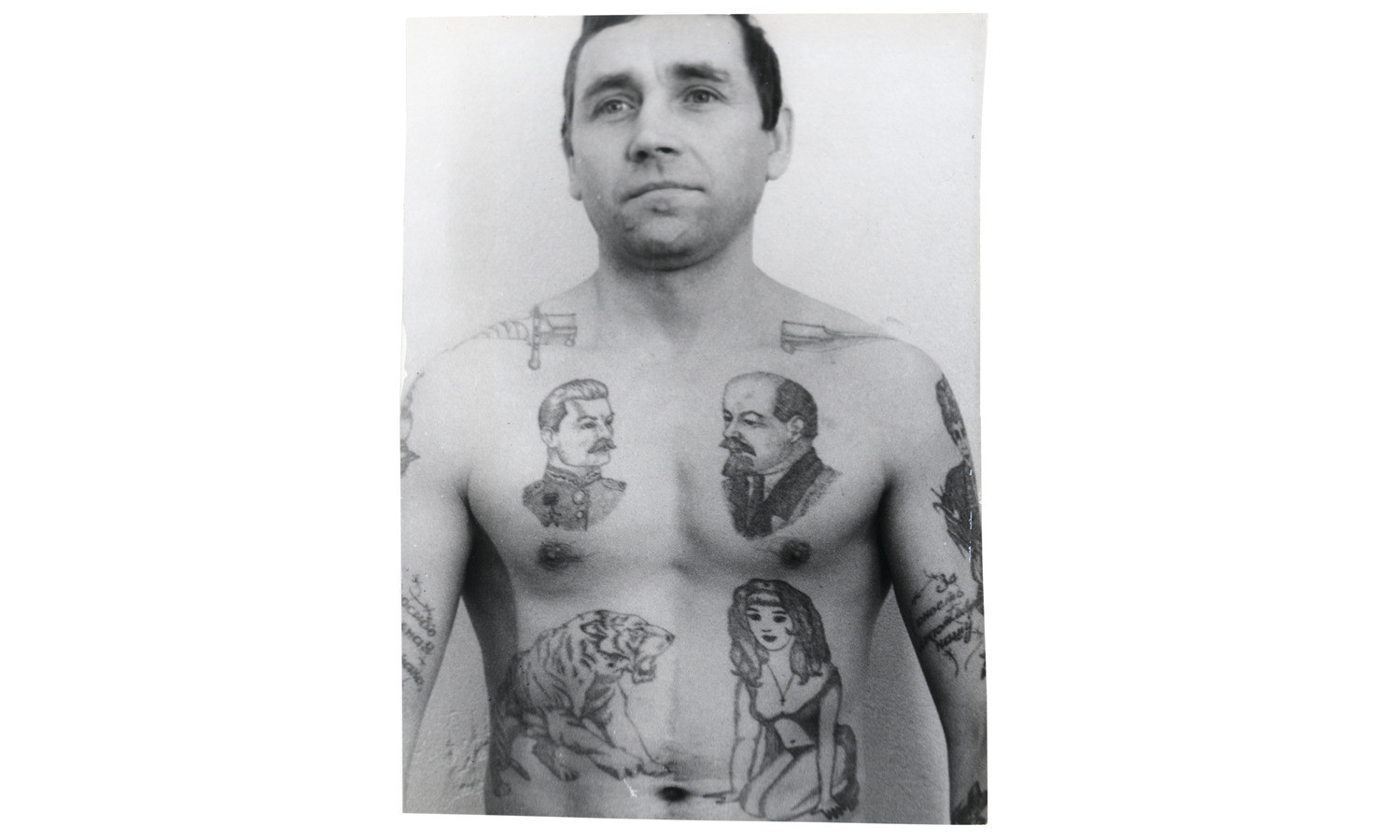

This inmate is not an authoritative thief, but has tried to imitate them with his tattoos to increase his standing within the prison. The lighthouse on his right arm denotes a pursuit of freedom. Each wrist manacle indicates a sentence of more than five years.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

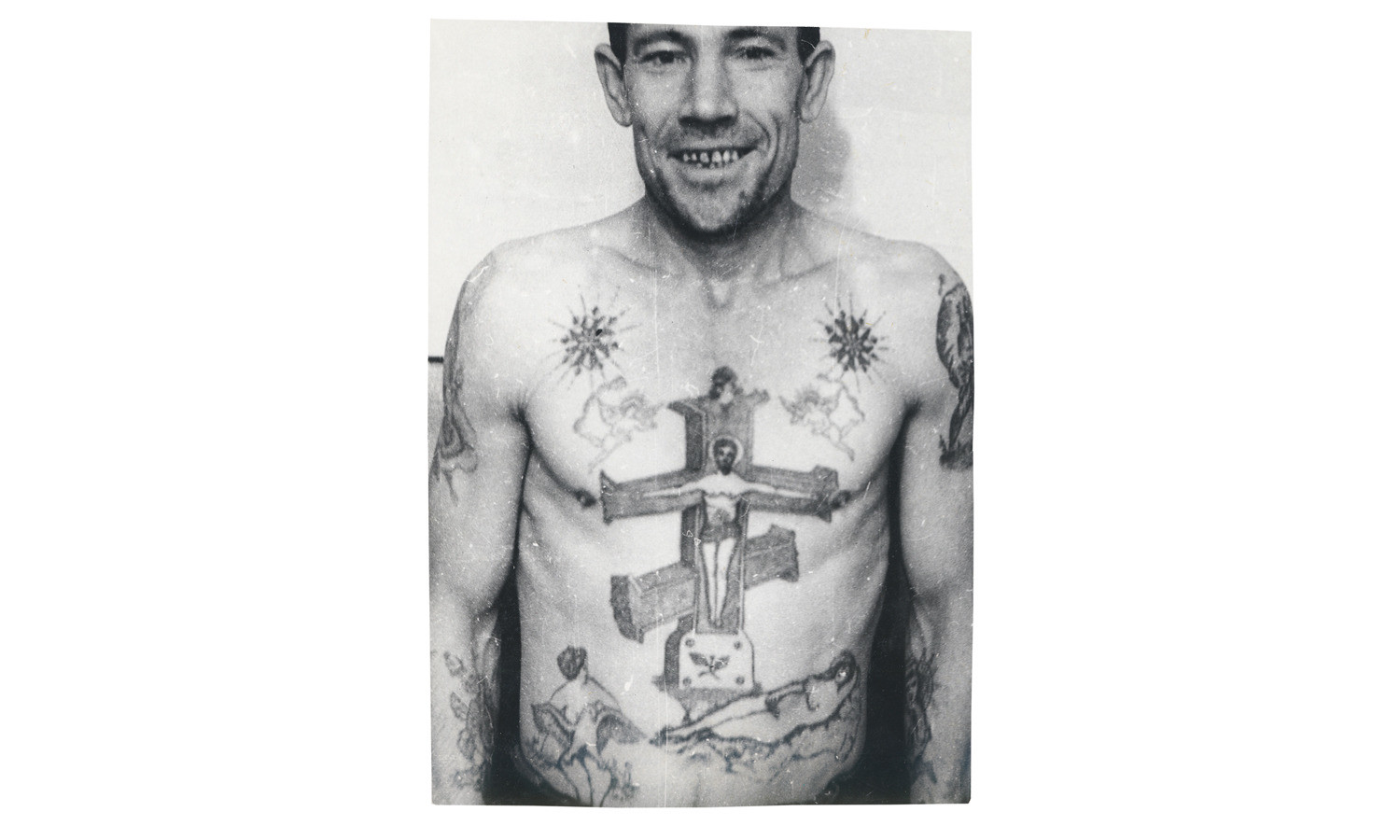

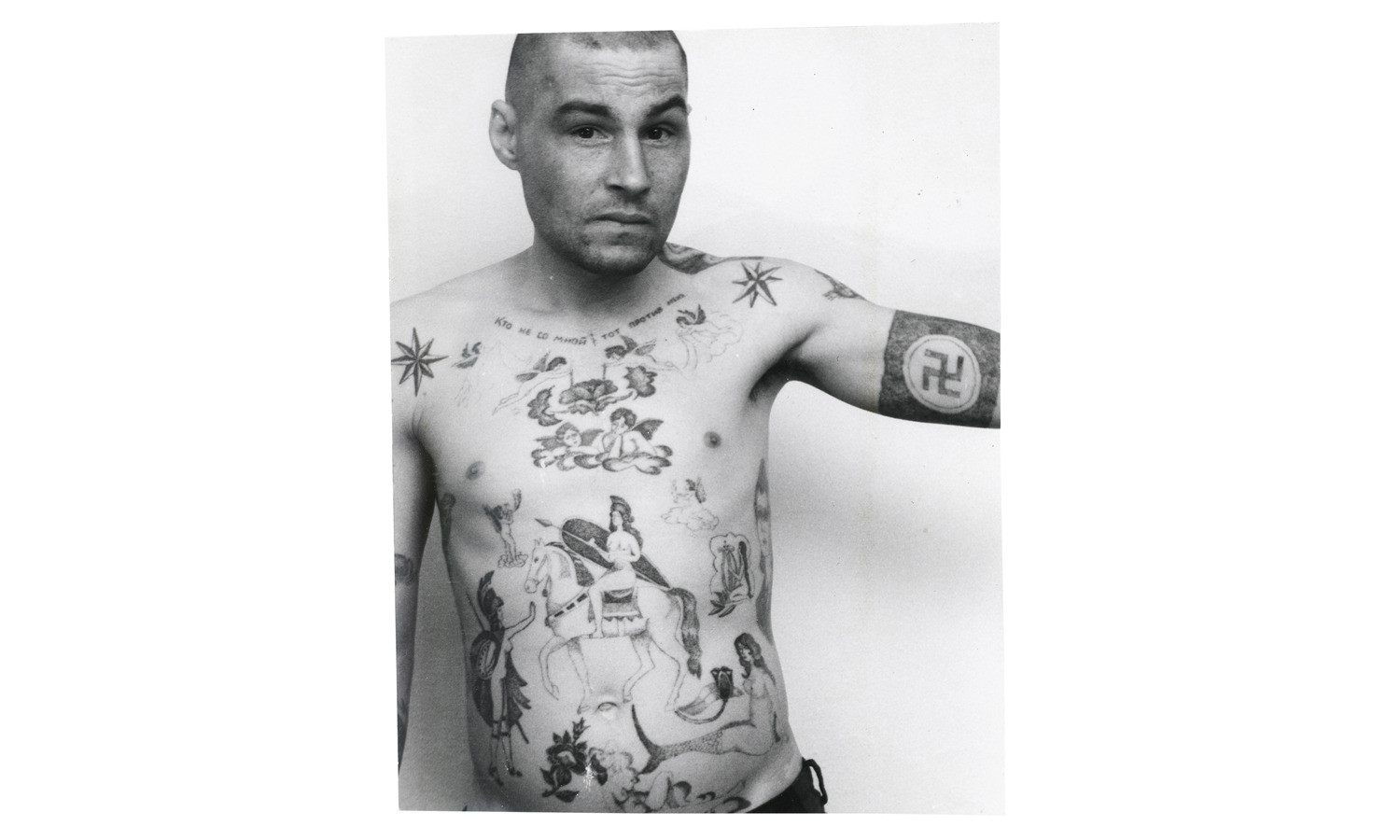

The lines placed between the points of the authority star on this inmate’s shoulders indicate that he’s been conscripted into the armed forces and has deserted to follow a criminal life.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

This prisoner is one of many who contracted syphilis, AIDS, or tetanus while being tattooed in unsanitary conditions.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

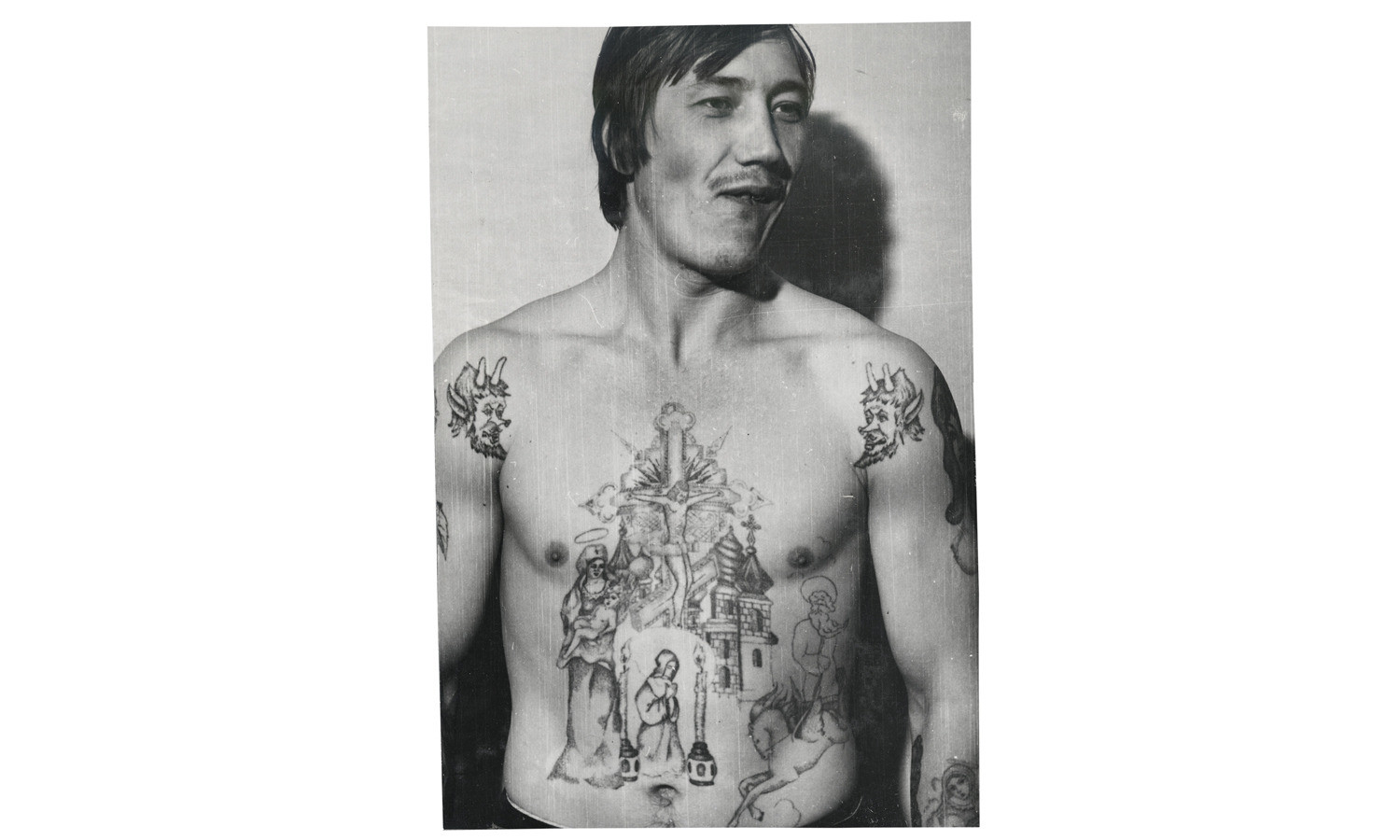

The devils on this inmate’s shoulders symbolize a hatred of authority and the prison structure. This type of tattoo is known as an oskal (grin), a baring of teeth towards the system.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

A dagger through the neck indicates that a criminal has murdered someone in prison and is available to hire for further hits. The drops of blood can signify the number of murders committed.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

A tattoo of a mermaid can indicate a sentence for the rape of a minor, or child molestation. Known in prison jargon as “amurik,” meaning “cupid,” these convicts are lowered in status by being forcibly sodomized by other prisoners.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

The skull and crossbones on the prisoner’s shoulders indicate that he’s serving a life sentence, and the tattoo of the girl “catching” her dress with a fishing line on his left forearm is one commonly inked onto rapists.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

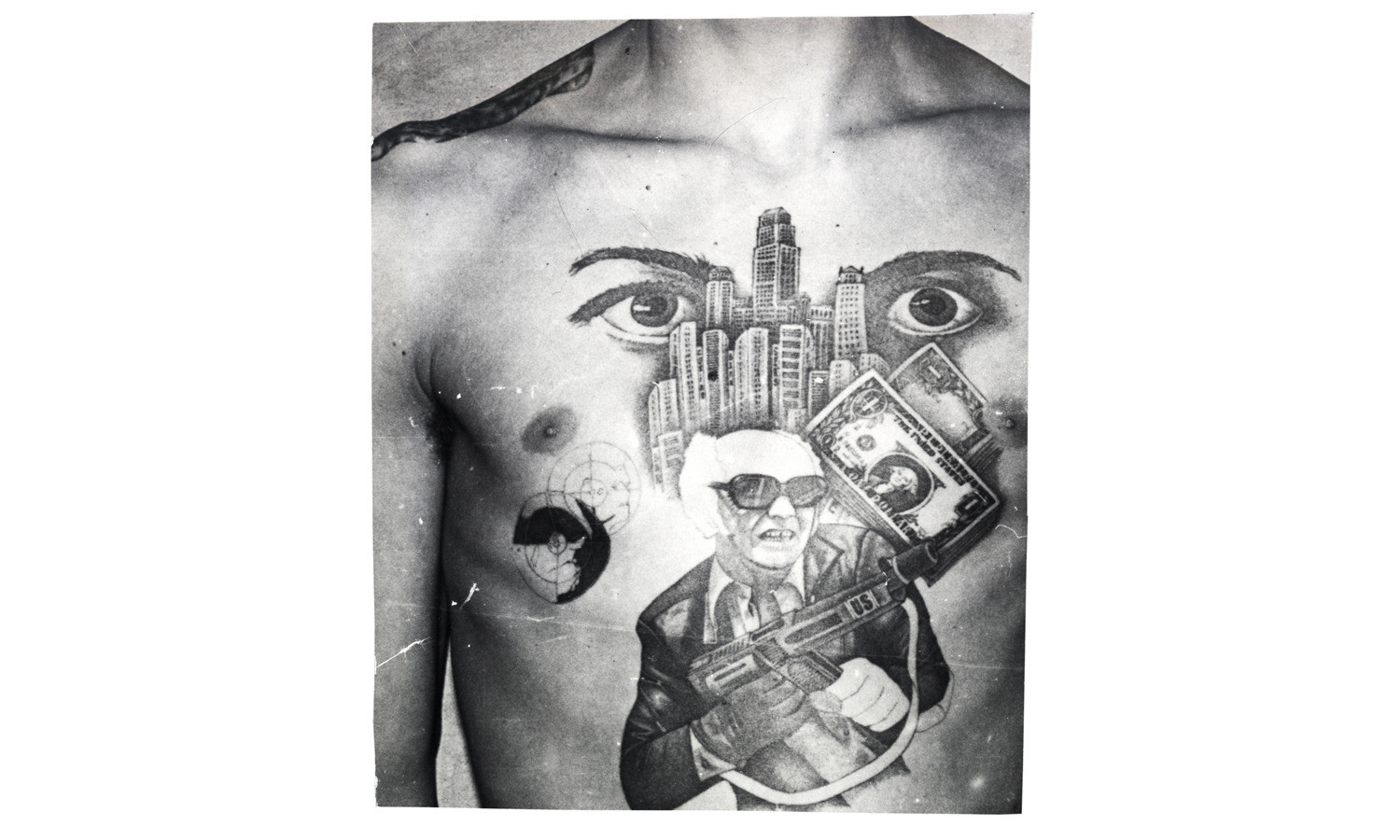

The dollar bills, skyscrapers, and machine gun with the initials US stamped on it convey this inmate’s love for the American mafia-like lifestyle. The eyes represent the phrase, I’m watching over you (the other inmates in the prison or camp).

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

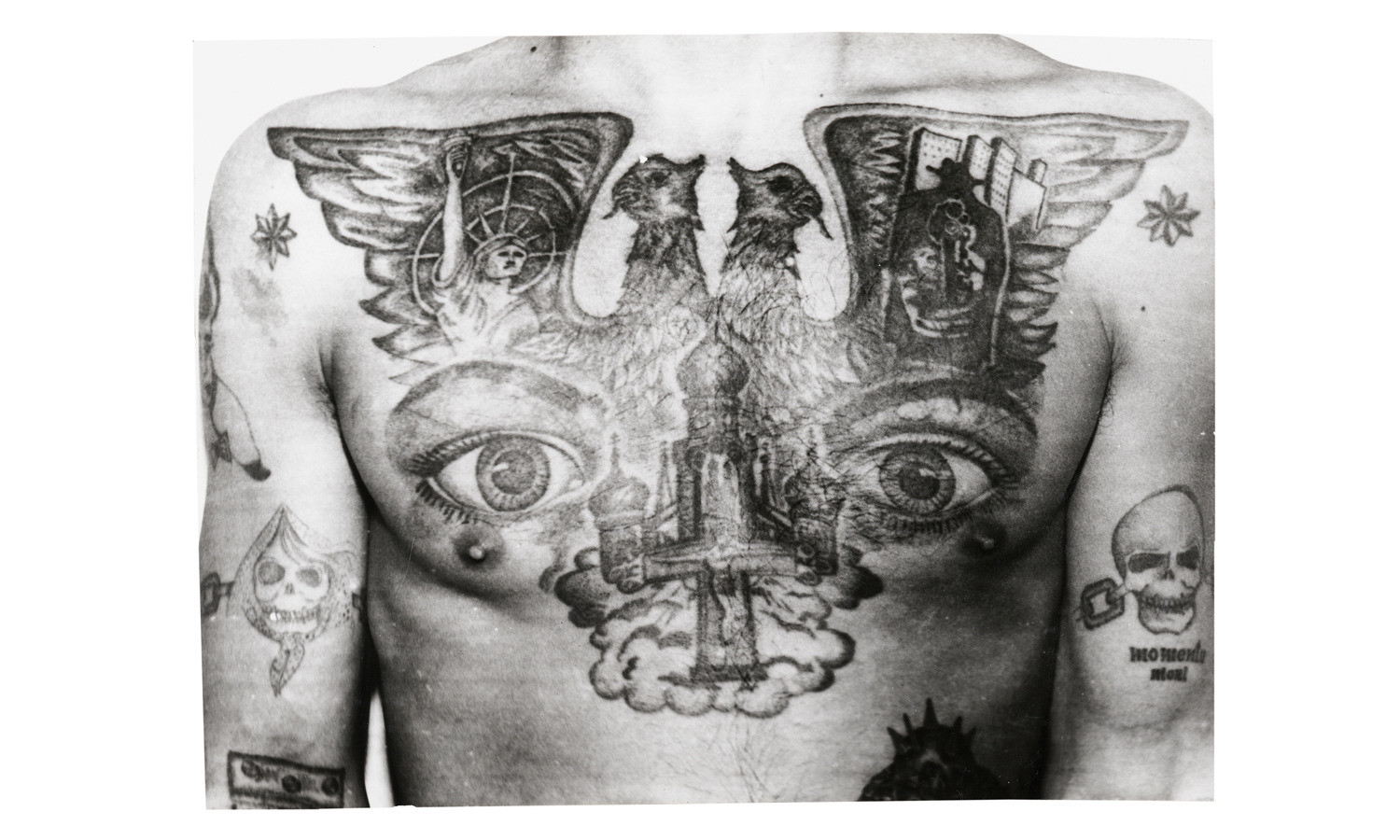

The double-headed eagle is a Russian state symbol that dates back to the 15th century, representing rage against the USSR. The Statue of Liberty implies a longing for freedom, while the dark character holding a gun denotes a readiness to commit violence and murder.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

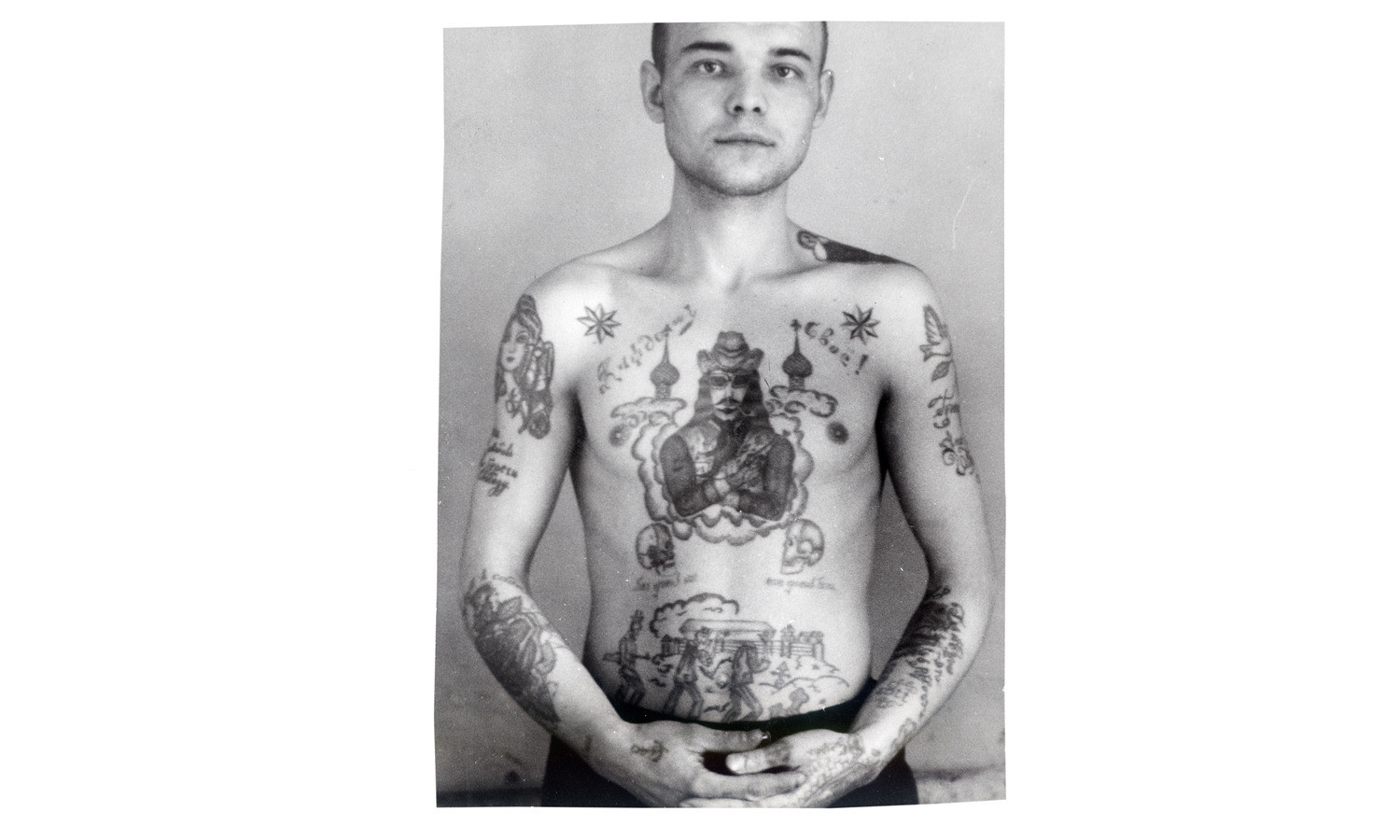

The text underneath the skulls reads: God against everyone, everyone against God. A cowboy with a gun indicates that this thief is prepared to take risks and is ready to exploit any opportunity. The dove carrying a twig (left shoulder) is a symbol of good tidings and deliverance from suffering.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

The rose on this man’s chest means that he turned 18 while in prison. The acronym “SOS” on his right forearm could stands for “Spasi, Otets, Syna” (Save me, father, your son) or Suki Otnyali Svobodu (Bitches robbed my freedom).

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

A bow-tie neck tattoo is often found in strict regime colonies. The dollar sign on the bow tie shows the bearer is either a safecracker, a money launderer, or has been convicted for the theft of state property.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

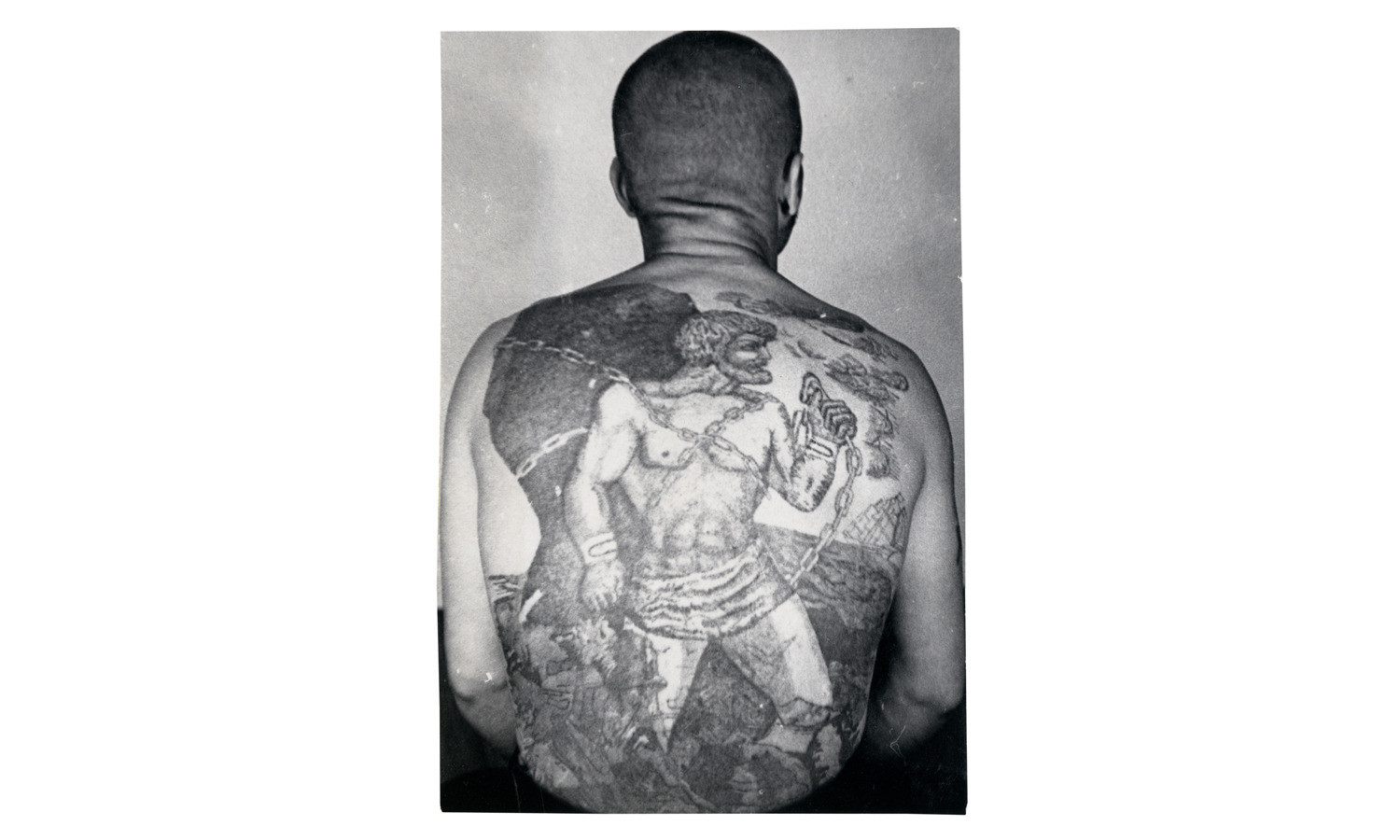

This tattoo is a variation on the myth of Prometheus, who, after tricking Zeus, was chained to a rock in eternal punishment. The sailing ship with white sails means the bearer does not engage in normal work; that he is a traveling thief who is prone to escape attempts.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL