After 50 prolific years spent producing masterful black-and-white photographs, Roger Ballen is ready to take his place as a master of the medium.

The past few years have seen major moves from the American-born, South African–based artist. He earned his own wing of Cape Town’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art, after the Roger Ballen Foundation contributed the largest financial donation from a foundation the brand-new institution has seen yet. Outside of photography, he’s gone from directing Die Antwoord music videos to his own short films. With a new retrospective monograph, Ballenesque, out October 10 from Thames & Hudson, Ballen declares for all the world to hear that he is an icon.

Videos by VICE

“I created this style called Ballenesque. Two or three years ago, I wouldn’t have been able to say that,” Ballen told me. “I created a reality that relates to how I express my life through photography. In a way, I couldn’t think of a better way to define the book. For people interested in art and photography, the pictures will lead them to a place in their mind that will challenge them.”

Below, watch an exclusive premiere of Ballen’s short film, also titled “Ballenesque,” created to introduce himself and the book to the audience.

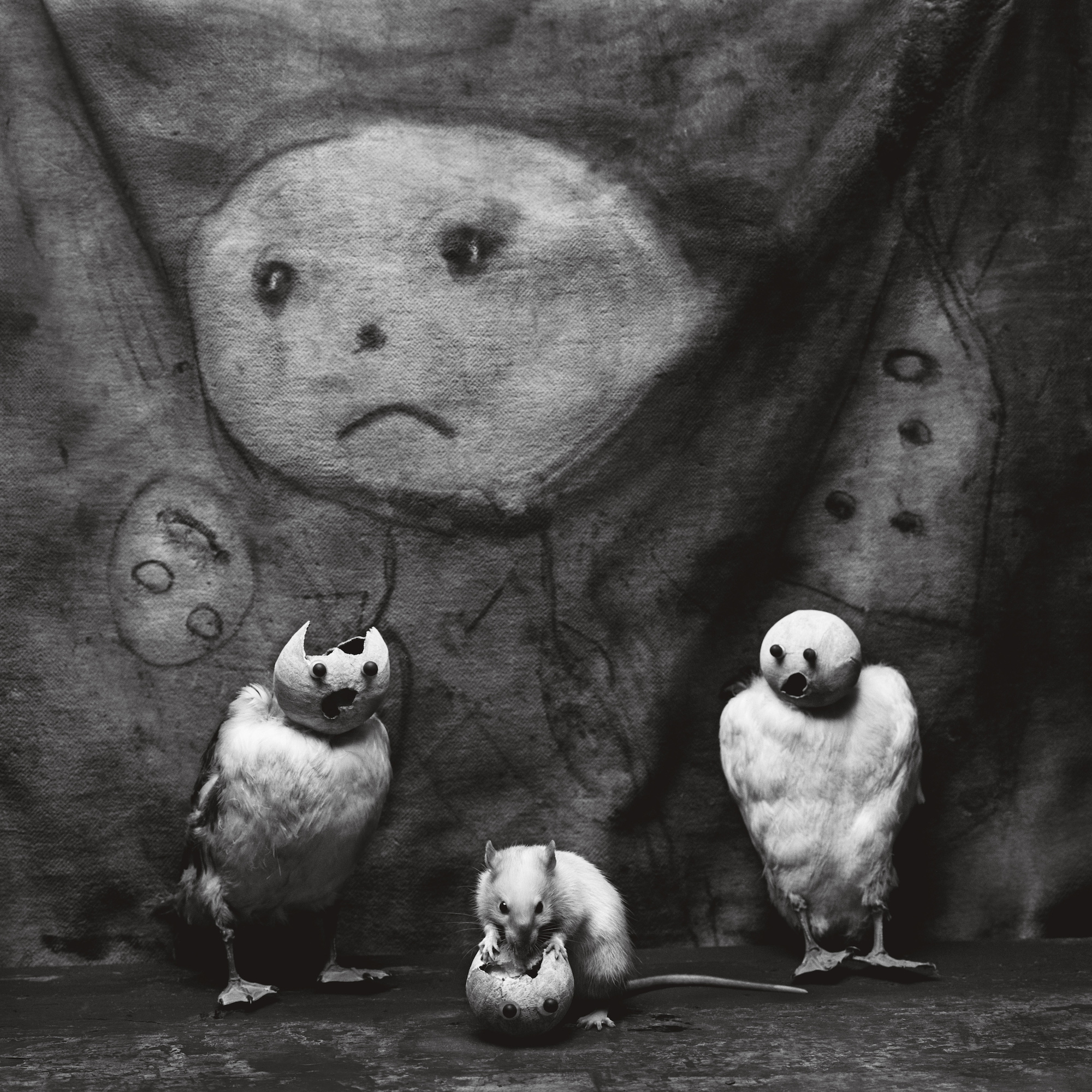

Ballenesque opens with an essay by historian and cultural critic Robert J.C. Young. In it, Young begins to define the mesmerizing, “instantly recognizable” quality of Ballen’s images, which he variously calls “prehensile portraits,” “aleatory assemblages,” “windowless walls,” and “dark junctures of disjunction.” When Young introduces these cornerstones of Ballen’s style, he writes, “We isolate four; you, the viewer of the photograph, may add a fifth to complete the secret.”

The rest of the book is a guided tour through Ballen’s work, complemented by 50 pages of the artist’s own anecdotes, autobiography, thoughts on technique, and philosophy. It all starts with blurry family portraits Ballen shot with a Mamiya camera he bought at 13 years old. He shares the first photo his that he really liked, a picture of a dead cat on the side of the road.

As he got older, he became a documentarian of 60s and 70s counterculture, from grimacing Vietnam War protesters to carefree nudists at Woodstock. Many photos from this period in his career are shown for the first time within the pages of Ballenesque. By 1979, Ballen had begun to travel the world, collecting snapshots of kids from New York to Indonesia that would be collected into a series called Boyhood.

When he moved to South Africa, Ballen became fixated on the human toll of apartheid. He traveled the impoverished South African countryside as a geologist, but photographed the people and places he saw along the way. He collected these images into the two series that made him famous, Platteland and Outland.

Also debuting in the new monograph are Ballen’s paintings from the 1970s, which informed his abstract photography in Asylum of the Birds and The Theater of Apparitions. “It was exciting to put those paintings in the book,” he said. Many of the paintings were lost when his father cleaned them out of their childhood home, but the ones that survive have been documented for Ballenesque. “I didn’t paint for 30 years, but in a way these set the foundation for my later work.”

By the end of the text, Ballen’s work seems to exist, like one of his paintings, largely within his own mind. “From about 2002 onward, you rarely see a human face in the photos,” Ballen said. His current project, teased in the final pages, is called Ah Rats. Now the vermin that have infested the edges of his work for years are at its center. In January, Ballen art directed Die Antwoord’s video for “Tommy Can’t Sleep,” which is full of the rats that are on his brain.

Ballen still walks Johannesburg looking for places to take pictures for around five hours a day. He spends the rest of his time with his family, administrating the Roger Ballen Foundation, and tending his collection of more than 100 pets. “There’s rats, snakes, chickens, ducks, lizards, rabbits, spiders, doves, pigeons, crows, mice,” he rattles off. Around 10 percent have names, including a bird named Icarus and a rat named Stoffel.

Icarus, Stoffel, and Ballen’s Johannesburg home are far from the roiling American political scene, but Ballen has some advice for young artists trying to distinguish themselves in a photographic era he describes as “amorphous” compared to when he cut his teeth.

“A lot of your ability to say something of value about the world is defined by your physical experience,” he said. “Involve yourself in things that have an actual impact on you. People just snap, snap, snap away—it doesn’t cost anything. They don’t have to put themselves on the line. If people want to say something of value, they have to put themselves on the line.”

Ballen is quick to clarify that he doesn’t mean photographers should risk physical harm by “jumping the White House fence” to get a unique photograph. “It’s years and years and hours and hours later that you’re developing an approach. My pictures are powerful because they access the subconscious mind. ‘On the line’ can mean psychological, as well as physical.” Years spent paying attention to places and people others would rather ignore are how Ballen put himself on the line. As a result, his photographs of outsiders help the rest of us look inward.

Ballenesque is out on Thames & Hudson October 10, 2017. Buy it here.