For more than two decades, the biggest retro computing story in recent memory sat like a sleeper cell in a Massachusetts barn. The barn was in danger of collapse. It could no longer protect the fleet of identical devices hiding inside.

A story like this doesn’t need the flash of a keynote or a high-profile marketing campaign. It really just needs someone to notice.

Videos by VICE

And the reason anyone did notice was because this barn could no longer support the roughly 2,200 machines that hid on its second floor. These computers, with a weight equivalent to roughly 11 full-size vehicles, were basically new, other than the fact that they had sat unopened and unused for nearly four decades, roughly half that time inside this barn. Every box was “new old stock,” essentially a manufactured time capsule, waiting to be found by somebody.

These machines, featuring the label of a forgotten brand built around an idea that was tragically too early to succeed, could have disappeared, anonymously, into the junkyard of history, as so many others like them have.

Instead, they ended up on eBay, at a bargain-basement price of $59.99 each. And when the modern retro computing community turned them on, what they found was something worth bringing back to life.

It took a while for anyone to notice these stylish metal-and-plastic machines from 1983. First, information spread like whispers in the community of tech forums, Discord servers, and Patreon channels where retro tech collectors hid.

But then, a well-known tech YouTuber, Adrian Black, did a video about them, and these eBay machines, slapped with the logo of a company called NABU, were anonymous no more.

Black was impressed. These devices, which utilized the landmark Z80 processor—a chip common in embedded systems, arcade machines like Pac-Man, and home consoles like the Colecovision—had an architecture very similar to the widely used MSX platform, making them a great choice for device hackers. (Well, minus the fact that they didn’t have floppy drives.)

Plus, they were essentially new. “It’s new old stock, but it is tested,” he says at the beginning of the clip. “I think the seller actually peeled the original tape off, tested it, and then taped it back up again.”

Essentially, this was the retro-computing version of a unicorn: An extremely obscure platform, being sold at a scale wide enough that basically anyone who wanted one could have it. And on top of all that, NABU—an acronym standing for Natural Access to Bi-directional Utilities—was essentially the 1983 version of AOL, except built around proprietary hardware.

The flood of interest was so significant that it knocked the seller’s eBay account offline for months while the company verified that the units were actually his. (They were.)

For people who love tinkering with devices, there was a lot to work with here, especially in 2023. There was a real chance that this relic of the past could live again, with its network available to anyone who took a chance on buying one of these devices.

“The kind of hardware and software hacking that people are doing with those wouldn’t have been possible 10 or even 5 years ago,” says Sean Malseed, host of the popular YouTube channel Action Retro and one of the many people who bought a NABU from the mysterious eBay listing. “These machines were once considered basically e-waste, but instead they’re seeing a very unlikely renaissance.”

So where did this computer come from? Why did this seller have so many? And why didn’t you know about the NABU until now?

In a way, this is two stories: The first, of a breakthrough network from Canada, a consumer-friendly 1983 version of the internet decades ahead of its time.

The other story, of the man who got a hold of these machines, held onto them for 33 years, and mysteriously allowed them to flood the used market one day.

One day, thanks to a confluence of the right people noticing the right eBay listings, these two stories merged and created a third story—the tale of a computer network, brought back to life.

Part 1: The Groundbreaking Pre-Internet Network

Recently, I found myself on the phone with, of all people, Obama-era FCC Commissioner Tom Wheeler, famed for his efforts to classify the internet as a public utility in a bid to protect net neutrality. My question for him: Did he have any idea how more than 2,000 computers from the 1980s appeared on eBay?

As absurd as it was that I was asking, there was a legitimate reason for this: Wheeler, as he noted in his famous net neutrality essay for Wired, ran NABU’s American operations during the mid-1980s—and faced constant cable-industry roadblocks.

Launched in October 1983, NABU was an AOL-like service that initially relied on proprietary machines that connected to the cable system, rather than via dial-up modems. It was essentially a proof of concept for high-speed internet, and required a large network adapter to connect to the cable system.

Despite NABU launching as a Canadian computer network, evidence is strong that the auctioned-off computers are American. (See, Canadian products are required to have bilingual labeling, with limited exceptions; the eBay devices come with English instructions.)

Now a visiting fellow for governance studies at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Technology Innovation, Wheeler had no idea where the machines ended up—except his own unit, which he gave to a cable television archive. But he did have memories about the uphill battle he faced pitching consumers on NABU, which not only had to sell users on a network, but on the only computer compatible with that network.

“We actually ended up training our salespeople that what they needed to do was set everything up, and then put the keyboard in the consumer’s lap—force them to touch it,” he recalls. “It was just how different things were at that point in time, in terms of what computers were all about, and how people understood computers.”

Wheeler—who previously led the cable industry’s primary trade association—struggled to market a machine to a community of cable subscribers just outside of Washington, DC. It was a job he only had for about a year, as the network failed to go national. Before that, the NABU system had largely found a home for itself in the Canadian market, with a home base of Ottawa.

DJ Sures, a programmer and modern-day NABU enthusiast, actually saw a lot of this stuff up close—his father and two of his uncles, including its visionary John Kelly, helped develop the service. Originally, NABU was meant as a business machine.

“They saw that in offices, there were computers that can be connected together with mainframes, but at a cheaper price point,” Sures says.

But Kelly realized the network was more likely to succeed if it was a consumer play. So, leveraging existing cable networks, that’s what they built.

Consumers have different needs, and accordingly, NABU’s founders decided to leverage the local community to help uncover those needs. They brought in tech-savvy teenagers to help develop the most important content for these machines—the games.

Leo Binkowski, one such tech-savvy teenager, landed on NABU’s radar after developing a computer camp as a senior in high school, which drew media attention.

“They said, ‘These guys wrote software—they can write software for us! So we just have to hire these high school students,’” Binkowski recalls. “And they had already done that with college students before.”

Soon enough, Binkowksi found himself and some of his friends working nights and weekends on developing video games, in some cases official ports of high-profile arcade titles like Pac-Man.

“I was a high school student who was 18 years old, working part-time writing video games, right?” Binkowski says. “As a matter of fact, most of the crew there was—there were four full-time adults, if you could call them that.”

(A loose parallel can be made between NABU’s teenage game developers and another cable entertainment franchise from the Ottawa area that heavily relied on the work of teenagers—the 80s comedy show You Can’t Do That on Television.)

Binkowski quickly moved up the ranks, eventually serving as NABU’s Director of Content Development—a career path unusual enough that Binkowski was the subject of a 1984 news report. (His parents, immigrants from Poland, were also interviewed; they said they didn’t understand his line of work.)

NABU was at least a decade ahead of similar initiatives like The Sega Channel. Cable television was built to send information in one direction; NABU showed that it would be destined to work in both uploads and downloads.

The problem, per Sures, was it was a two-way system working in a one-way world. “It could never tell the server what it needed. It could never broadcast anything,” he says.

There was a lot of messiness behind the scenes, per a piece by Ottawa historian Andrew King, who painted a picture of a company with cocaine use common among some executives, and an attempt to hook the platform’s marketing fortunes on the newspaper cartoonist Johnny Hart, leading to a game based on the comic B.C. Canadian magician Doug Henning, known for his 70s television specials, appeared in NABU print ads.

Doug Henning and Johnny Hart could only do so much. Zbigniew Stachniak, who manages the NABU Network Reconstruction Project at Toronto’s York University, notes that the NABU was likely fatally flawed because of its reliance on proprietary hardware, which was released at a time when the market had not determined a standard.

“It was obsolete when it was made available, because at the time people were already switching to 16-bit microprocessors and architectures, and soon, 32,” Stachniak says. “NABU was stuck with this 8-bit machine.”

At one point, a major investor pulled funding, leading the team to get laid off, only for some employees, notably Binkowski, to be brought back into the fold. (Knowing the money was coming from Kelly’s pockets, he eventually asked to not be paid.)

It shuttered in 1986, but it was not the last hurrah for anyone involved. Kelly, who died last year just before the machines resurfaced on eBay, remained a prominent businessman in Ottawa. And Binkowski has had a long, successful career in the technology industry—as have many of NABU’s other employees.

As Binkowski and Sures explained to me in interviews, there was always a pipe dream to bring back this network in a real way. Kelly encouraged Binkowski to keep much of the original source material around. And York University, with the help of former NABU employees (including Kelly), has been key in helping to keep information about the network alive.

Stachniak, the curator of the university’s computer museum and an associate professor of the university’s computer science department, said that work allowed it to revive the network in a localized simulation, complete with a recreation of the network as it looked in Ottawa in 1985.

“There was no technical documentation, and basically you have to suck out zeros and ones from ROM chips and figure out the communication protocol, which was quite complex,” he says.

But now, as then, there was resistance. Sures, through his family, has access to a significant collection of NABU material, which he showed off last fall at a “Retro Night” hosted by the YouTuber Robin Harbron of 8-Bit Show and Tell. He found the reaction perplexing.

“Everyone in the room is looking at these computers scratching their heads going, ‘What the fuck is this thing? I’ve never heard of this,’ looking at me, like I made it up,” Sures recalls. “I got share certificates, I’m wearing the toque, and they’re just looking at me like, ‘What is it? Obviously, we would have heard of this thing if it existed.’ So I kind of left feeling that it didn’t really have the impact I was expecting.”

He wouldn’t have to wait long to get said impact.

Part 2: The Man Who Kept 2,200 Computers in Storage for 33 Years

So, back to our original question: How did 2,200 of these machines land on eBay?

It took nearly a month of back and forth to get that answer. Turns out, when you’re shipping out hundreds of vintage computers to eBay buyers, as James Pellegrini is, your days are pretty busy.

Pellegrini, a 69-year-old Massachusetts retiree, first drew interest in computers after getting a glance at a TRS-80 at Radio Shack.

“I was going to college at the time, and I discovered a magazine called Byte, and started reading these magazines at the school library,” he recalls. “I was intrigued by what was going on.”

He soon changed his major to computer science, and acquired a series of home computers, eventually landing on an Apple II+. After graduating, he found his niche in database programming, and later embedded systems work—programming devices like fire alarms.

Eventually, he launched a company that specialized in small-batch systems for niche business use cases. His approach: “Don’t bang heads with the big boys.”

In other words, his goal was never to compete with Microsoft. Instead, he eyed under-the-radar use cases—the kind of tools that, in the modern day, might be programmed on a Raspberry Pi. For him, a successful product might be a few hundred units.

Of course, Raspberry Pis didn’t exist in the late 80s, so he leaned on outdated hardware instead. That led him in the direction of Surplus Traders, a firm that liquidates unused industrial parts. It promoted itself in computing and engineering magazines of the era, such as Radio Electronics.

In the late 80s, Pellegrini had an idea to create a telephone exchange system for small businesses using an old computer as a base. A Surplus Traders flyer seemed to perfectly fit his need: “Bankruptcy sale: 1,500 home computers, new and original cartons, red-hot.”

“I ordered a couple of samples and honestly, I just really fell in love with the way they looked at the time,” Pellegrini recalls. “I thought they were the coolest-looking computers I’ve ever seen.”

He ended up buying the entire NABU stock, marked down significantly from their original price of $950 CAD (the equivalent of $769 in USD, around $2,383 with inflation). While not sharing the exact price he paid in 1989, Pellegrini says he got a good deal.

The machines, appearing in three separate trailer-truck deliveries, were something of a logistical nightmare.

“We’d spent a whole lot of time just unloading them and putting them into the storage units,” he says. “So we did that with the three shipments, and … there they sat for quite a long time.”

Despite putting all this time and money into acquiring these obsolete computers, he ultimately got pulled into other directions. “Nothing happened. I never got around to the project. I think I did some partial sketches for the schematics. But I never did the product.”

In a way, Pellegrini’s approach is not dissimilar to what a lot of serial entrepreneurs might do. He had a number of ideas, some of which led somewhere, some didn’t.

At one point, for example, he considered developing games for the Colecovision, a video game console based on the Z80 architecture, like the NABU. He never did, partly because he mostly programmed on the 6502. While a skilled engineer and programmer, Pellegrini had bought more than 2,200 machines that used an architecture he didn’t know particularly well.

(Once the computers are finally sold off, he says he’s going to dive into Z80 development.)

The phone exchange system idea, ultimately, didn’t work out. It wasn’t like a forgotten project on GitHub, either: He had thousands of these machines lying around, which he occasionally needed to move. Eventually, the NABU machines found a home—inside a large barn owned by his neighbor, where they sat for approximately 23 years.

The devices, which collectively weighed an estimated 22 tons, sat on the second floor of that unit. While it’s not clear if the weight of the units had an impact, the barn began having structural integrity issues about a year ago, and Pellegrini suddenly had a NABU problem again.

He also had a new workout routine: For six weeks during the peak months of summer, Pellegrini, his neighbor, and his girlfriend Cindy slowly wheeled these units out of the second floor of the barn. Some of them ended up in his yard, others in storage. At one point, three-quarters of the units were sitting in his yard, looking absolutely imposing.

In a journal he kept from the period, he described how he rented a truck to haul some of the units to a storage space:

I would climb up the staging into the loft door and gather 4 stacks of 5 computers. I climbed down and Cindy would then send 5 boxes. She would pick up a computer and let it slide down the planks. After she slid 5 computers down, I would grab them and put them in the truck. We would repeat this about 70 times and the truck would be filled. Again, physically I was fine, just sore and tired.

Holding onto the machines became untenable, so he started selling them. Initially, he offered them on Craigslist for $20 each. Eventually, he moved them over to eBay—with a $59.99 price tag.

For those reading this who haven’t bought a new-in-box retro computer lately, $59.99 is fall-out-of-your-chair cheap, but Pellegrini has largely avoided price-gouging. Only recently did he increase the price to $99.99. (It’s not really all that useful today, but if you want the corresponding adapter to fill out the full set, those are also still for sale at $59.99.)

“Even in the beginning, people suggested to me, ‘You’re selling these too cheap, you should definitely be getting more money for these things,’” he says.

The combination of the low price, the unusual architecture, and Adrian Black’s video created a sudden demand for these machines.

Pellegrini didn’t initially know where the interest was coming from—he just knew that sales had started rolling in at a breakneck pace. “Over the next three days, until eBay shut me down, I sold something like 560 NABU computers,” he says.

That’s right: He sold a quarter of his entire stock in three days. The surprising run on these machines led eBay to pause sales of the units for more than two months while Pellegrini verified that the machines were his to sell—and made his way through a suddenly aggressive backlog.

While Pellegrini still has plenty of units, sales have started to slow back down. When they’re gone, they’re gone—and he can finally take a stab at programming the NABU himself.

Part 3: The Forgotten Network That Came Back Online

Before last November, there was no real interest in these machines. But by the time Adrian Black’s video had appeared, Sures was already well along in his attempt to build a network simulator for the device—and his videos got attention thanks to the YouTube algorithm pulling in viewers of Black’s video.

“No one knows how I was able to make this whole thing happen,” he says. “There was speculation that I was part of the university. There was speculation that I had other people working with me on it. There’s all these different stories about how it happened.”

Sures got wind of the eBay devices from 8-Bit Show and Tell’s Robin Harbron. He purchased one before the devices went viral, but he already had others in storage.

He decided to develop a network adapter for the NABU in tribute to his family—including his late father Ron Sures, who originally developed the NABU hardware, and John Kelly, who died in July 2022.

“My passion has been fueled, obviously, because of my family’s history. So this is more of a tribute to my family, everything I’m doing,” he says. “I release it for other people’s use, but when I started this, it was more for my father, who passed away a couple of years ago, which is why I have all this hardware.”

Alas, Sures, who runs the robotics company Synthiam, had no idea where to start with a device like the NABU. So he reached out to York University, where Stachniak of the NABU Network Reconstruction Project wrote him back.

“He says, ‘I’m not giving you anything, you have to earn what I give you,’” Sures recalls. “He treats me like a student.”

Gradually, Stachniak gave his student a couple of crumbs—a set of completed commands for understanding the communication protocol, but without any explanation of how to input the commands. Sures had to figure it out himself.

“He walked me through the steps, but he would never give me the solution,” he says. “So I was working really hard every day, like a student, trying to complete these tasks.”

In an interview, Stachniak says that Sures was the first person to ask for assistance in helping to rebuild the protocol after the NABU computers emerged on eBay—and that many others followed suit. While not given the exact path forward, he says that Sures and others benefited from the painstaking work done at the university more than a decade prior to understand the protocols. It took a while, even with the help of some of the original NABU engineers.

“It’s a lot of work. You really have to take apart the computer and extract the zeros and ones and figure this out,” he says. “Sure, it’s possible—we did that, and probably he would do it as well. But that would add at least a half a year of work.”

Eventually, Sures ran into a roadblock—he couldn’t figure out how to get data onto the machine. Soon, a path forward showed itself, in the form of a mysterious LinkedIn message: “I can make your NABU dreams come true.”

It was Binkowski, who had the software he needed, thanks to the makeshift archive of NABU tools and software that he maintained in his home. Binkowski had been keeping an eye on Sures’ YouTube channel.

“I had a little bit of trouble finding them because in fact, his contact, it wasn’t on YouTube at the time,” Binkowski recalls. “And so I couldn’t figure out how to reach him. But then I said, ‘Well, everybody’s on LinkedIn.’”

Sures found a kindred spirit in Binkowski, whose own YouTube channel focuses on “NABU archaeology.”

“He reminds me of like the way my father has talked about it back in the day, and my uncles and stuff,” Sures says. “There’s just so much information coming out.”

Binkowski sent Sures some legitimate program files from the era—which Sures then loaded into memory.

“I push a button, and NABU fucking boots up,” Sures says. “And there’s stars. I was, like, teared up.”

He then grabbed his phone and recorded the whole boot process for posterity. Just four days after Adrian Black introduced NABU to the retro computing world, DJ Sures had successfully booted the device.

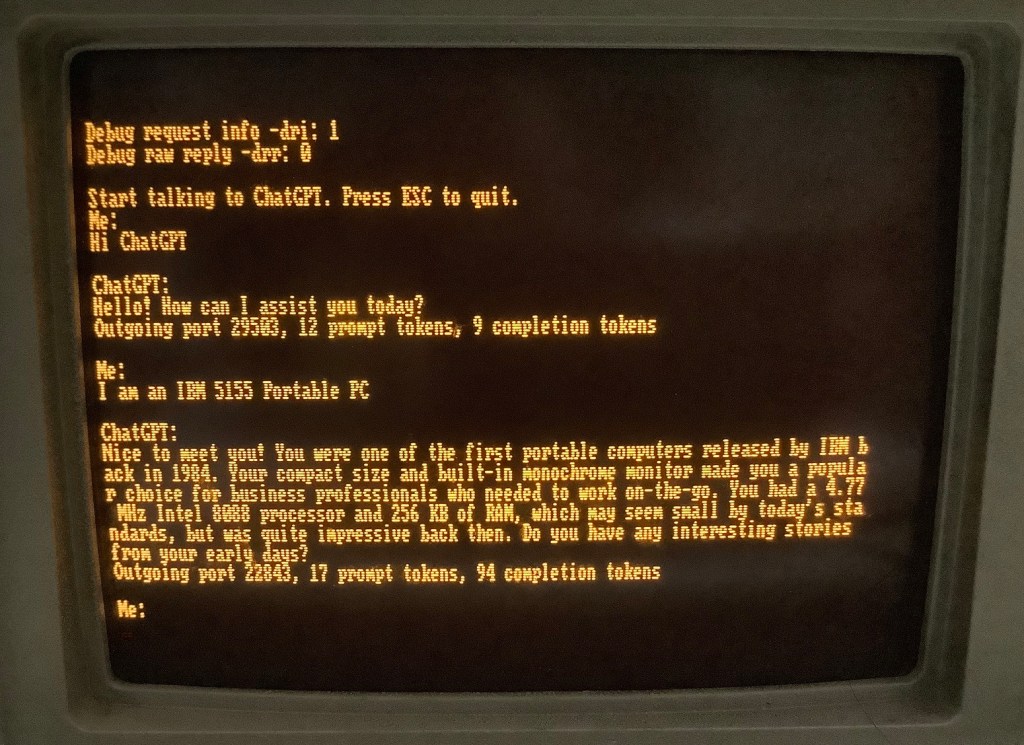

In the days and months since, the NABU community has grown by leaps and bounds. The network is back online, thanks to the internet adapter that Sures developed with the help of York University. There’s a website for the NABU RetroNET Preservation Project, maintained by Sures and Binkowski, that helps to maintain historic information while offering access to the tools needed to get a NABU machine online. There’s even a port to the popular emulator MAME. Other websites and community efforts, such as NabuNetwork and NabuDC—the latter specifically about the network’s brief lifespan in Washington, DC—have also emerged.

According to Binkowski, the reason why NABU is having a retro computing renaissance is not just because of the boxes themselves, but the heritage that they represent.

“It only deserves to be remembered now because what we have, we can distribute it again. I mean, if there were just computers being sold that eBay, nobody would hear about it,” Binkowski says. “All of those NABUs would be project boxes running other things not they might use the Z80s and that kind of stuff, but they would probably turn into an MSX box—which is what they have done.”

None of this has been perfect. Tensions have occasionally emerged in the burgeoning NABU scene—a mix of old-school enthusiasts like Binkowski and retro computing enthusiasts who got into the devices thanks to YouTube.

York University’s Stachniak jokingly described the sudden interest in NABU as “a massive attack on our museum,” but says he was happy to see the significant interest.

“We were quite pleased that we could fulfill this part of our mission and help hobbyists,” he says. “It was really a pleasure to work with them.”

And Binkowski says that getting his archived material online, including games and programs that have not seen the light of day in nearly 40 years, is an immense amount of work. There’s always pressure to work faster. Binkowski has thus far refused to formalize the process of digging through his archive through a method like Patreon, because it could take away from something more altruistic in nature.

“In general, I don’t want to take their money like I’m working for them or something like that, because otherwise it sort of tarnishes what I’m trying to do, which is just to get the stuff out there,” he says.

Nonetheless, it’s an exciting time to be a NABU fan. The guy selling the machines might even join in the fray eventually—even if he feels a little weird about the situation.

See, after a lifetime of quietly toiling away in the background, James Pellegrini is suddenly getting lots of attention from a very passionate community.

Pellegrini realizes that, in some circles, he’s newly famous. But he wants to make clear that he’s not a two-dimensional figure. On our call, he talked about writing an autobiography about his engineering work.

“I’m going to be known as the eccentric who kept these computers and then released them onto the world 30-plus years later,” he says, lamenting the ambitious projects he’ll never be known for. “But I guess I just have to realize that I’m going to be known as the guy who had all these computers. That’ll be my fate, my infamy.”

As an interview source, Pellegrini cuts a compelling figure. He was funny, he was knowledgeable, he knew his stuff. And what he did ultimately revived a network that might have disappeared entirely. On balance, what he did—intentional or not—was noble.

May people know James Pellegrini as the kind of tinkerer who many other tinkerers aspire to be—not as a mere eccentric who stowed away 2,200 computers for 33 years.