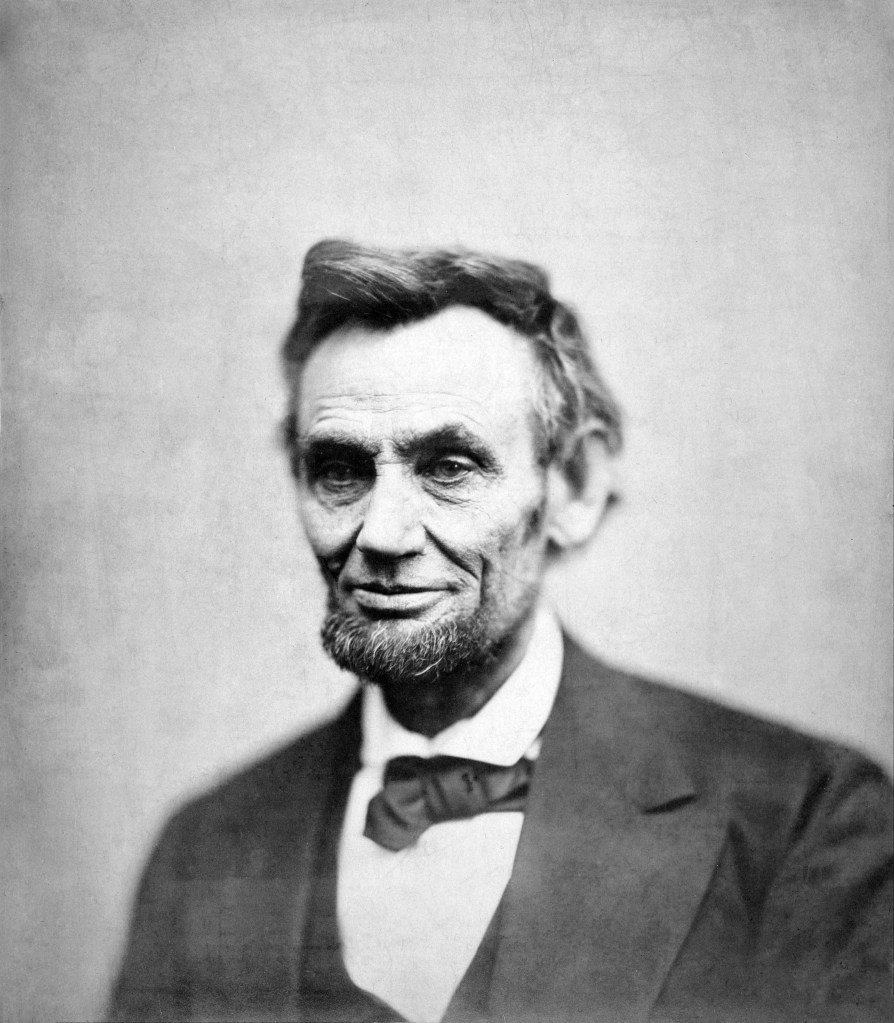

The internet is many things, but sometimes it just seems to be a way for rumors, hoaxes, and lies to spread like black mold. The most high-profile incidents of viral nonsense involve President Donald Trump making evidence-free statements about an imaginary terrorist attack in Sweden and the Obama administration tapping his phone. But there are examples of untruth every time you open Facebook and read about Klansman committing suicide because Harriet Tubman will be on the $20 bill, or scroll past the Republican Party’s Twitter account when it’s inventing Abraham Lincoln quotes.

The researcher who goes by the nom de plume Garson O’Toole is familiar with the latter kind of falsehood—as the “Quote Investigator,” he runs a charmingly web 1.0-looking site dedicated to tracing the origins of quotations. It can be a complicated enterprise. People misattribute pithy quips to famous figures, sayings are altered and removed from their original contexts, and the record of who authored what line can be muddled. Case in point: On St. Patrick’s Day, Trump quoted what he referred to as an “Irish proverb,” saying, “Always remember to forget the friends that proved untrue. But never forget to remember those that have stuck by you.” Savvy journalists with access to Google quickly determined that the proverb was actually written by a Nigerian man—except that turned out to be wrong, too. As O’Toole discovered when he dug into it, the words probably come from a poem written in 1936 by a guy named Levi Furbush.

Videos by VICE

On April Fools’ Day, O’Toole came out with the book version of his endeavors, Hemingway Didn’t Say That, which goes into daunting depth about where some of the most famous sayings of all time actually originated. It’s in one sense a niche endeavor—most people care more about the sentiment of their favorite quotations than where they originated—but it seems timely or even urgent. When most of the country, including some of the people running it, are having a difficult time sorting fact from fiction, it’s refreshing to know that someone is exhaustively searching for truth, poring over sources, and coming back with footnotes.

I spoke to O’Toole over the phone last month in advance of his book coming out. Though he didn’t want to tell me much about himself—he says that’s out of a desire to let his work speak for itself—we had an interesting discussion about fake news, being wrong on the internet, and what you should do if you see your Facebook friend posting a fake Winston Churchill quote.

VICE: You’re a full-time quote investigator. What is it about that sort of research that appeals to you?

Garson O’Toole: Well, I enjoy finding out the hidden history behind some quotations. And in fact, there’s a good example of that with this quotation that’s used often at graduation exercises, when they’re trying to inspire the new graduates. It goes, “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny matters compared to what lies within us.” And those words are attributed to some big figures, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. But it turns out that none of those famous people is responsible for creating it. Instead, it first appeared in 1940, in a book called Meditations in Wall Street. And initially, the book was anonymous—a person named Albert J. Nock wrote the introduction, and William Morrow was the publisher, so the quote was attributed to those people. Eventually, in 1947, they actually did find out, and this was published in the New York Times: It was a securities trader named Henry Stanley Haskins. But there’s a problem with attributing it to him, because he ran a securities firm that failed—he was cited for reckless and unbusinesslike dealing, and basically expelled from the stock exchange. So you can imagine a graduation speaker is not gonna be giving this nugget of wisdom and then saying, “And this is from Henry Stanley Haskins, the disbarred trader.” So it’s much better to assign it to these famous people.

“You’d think, How can these thousands of people be wrong? But it turns out that they are.”

Do you think that it’s important who came up with a quotation like that? Does authorship really make a difference?

Well, one of my goals is to give the genuine authors credit. Ethically, I think that makes sense. It’s true that people often don’t particularly care about who specifically said something—they prefer that it be a famous person. Some might be interchangeable in the modern mind. Like, if you say, “Ralph Waldo Emerson,” people might not have a strong sense of his personality or values. But I do think it makes sense to try to credit the right person. One reason that things get misquoted is that when people go online and they type in some phrase from a quotation, often near the top of Google or Bing will be one of these major databases, like Brainyquote. And it turns out that they’re filled with misinformation, but people don’t know to distrust the citations provided by these websites. So they simply repeat them. And sometimes they type in a phrase, and it appears that a thousand websites all say Mark Twain said it, and so they believe that it must be true. You’d think, How can these thousands of people be wrong? But it turns out that they are.

Do you think that the internet has sped up the process of misattribution or made it more likely that a quote would be misattributed?

I think that it has speed up the dissemination of misinformation for quotations. There was that recent example in which Donald Trump was meeting with the leader of Ireland.

Watch this video about a gay Mexican pro wrestler who became the “Liberace of Luche Libre”

Do you see a connection between the fake news phenomenon everyone is talking about and your work?

Well, one connection would be that the misquotations have a long history, hundreds of years. To the extent they’re viewed as fake news, fake news has been around for hundreds of years. There were fake Mark Twain quotations that gained distribution even in his lifetime and continued onward. The Nigerian poet example, I think [that story spread] because it was relatively shallow research, or perhaps doing the correct kind of research is more difficult. And they didn’t think to call upon me. Actually, I was called upon by Ben Zimmer of the Wall Street Journal—he is the person who actually found this earliest citation, on March 3, 1936.

Recently people have been becoming a little bit more skeptical about things they read online—it turns out, for example, that a lot of the snippets Google puts at the top of search results are incredibly wrong. Do you know about this phenomenon?

In fact that happens with my own website. If you type in some quotations Google has created of these cards, or whatever they call them, that display snippets from my website, and sometimes if you just read that snippet you might get an incorrect impression. You really have to click through to get the full story. I mean, they have great programmers working on trying to extract that information, but it’s an enormously difficult task. And so it makes sense to click through and find the full context.

Do you see yourself as being aligned with the movement of people who are trying to get regular internet users to be a little more skeptical of what they see online?

I aim to sensitize people to the fact that there’s a lot of misinformation. Years ago, I was guilty of assuming that the quotation information I read in popular magazines or newspapers was accurate. I didn’t even think to be skeptical about it. There’s a process of being sensitized to realizing that just because you read this in your local newspaper, just because you read it on a website, or even a thousand websites, you have to dig deeper. And in particular, what you want for quotations is a citation, and that is what exact book does this appear in, what page does it appear on, what newspaper did this appear in? And that’s often not given with quotations. In some cases, it makes sense not to give that; you can’t make an article too long, you don’t want to have footnotes everywhere. But in that case, you have to go to a reliable quotation dictionary, like, say The Yale Book of Quotations, which I highly recommend, or my own book, and see what it has to say. Especially if you’re writing a book or a newspaper, you’re composing it, and you want to give reliable information to other people.

If you want to make the internet a little more accurate and stop the spread of fake quotations and see someone posting a misattribution on Facebook, is it OK to leave a comment being like, “Actually, Winston Churchill didn’t say that,” or is that a bit of a jerk move?

In some contexts, it can be obnoxious and irritating to people, and they don’t respond well; they may get angry and defensive. Someone might say, “Well, it doesn’t matter who said it, it’s still true. It’s still an important quotation.” So it’s best to give that feedback privately, and not try to publicly embarrass people, in some cases you can just let it slide. But the problem is if someone rises to a position of authority, such as the presidency, you’re helping them by not letting them be embarrassed in the future. So if you’re doing it constructively to help them out, and you’re doing it privately, then I think that it’s a good idea. You shouldn’t try to publicly embarrass people.

Does it worry you in any way when people in positions of high power—like the president—misattribute quotes? Do you see that as a sign of carelessness, or a willingness to believe whatever they’ve seen on the internet?

They need better advisers. Or the people doing the research for them have to do a better job. In the Congressional Record, you find various congressmen who are misattributing quotations. Even President Obama, there’s an example where he misattributed a quotation, and Hillary Clinton, in one of her books, has a misattributed quote. So it’s a nonpartisan problem.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Buy Hemingway Didn’t Say That on Amazon.

Follow Harry Cheadle on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Frank Hoensch/Redferns via Getty Images -

Castlery -

Illustration by Reesa. -

Screenshots: Telltale Games