Postscript is Cameron Kunzelman’s weekly column about endings, apocalypses, deaths, bosses, and all sorts of other finalities.

Heads up, this post contains some spoilers for Watch Dogs 2.

Videos by VICE

Hey Austin,

I think we both have similar opinions of the original Watch Dogs: It has a lack of personable characters, and it has one of the most nihilistic and bleak views of the world that games have produced. It was a game about hitting people in the face with a metal rod as a “nonlethal” method of taking them out of commission—it was brutal. Aiden Pearce gunned down dozens of people across dozens of different locations in cloudy fake Chicago. It’s hard to square that design decision with the amount of real-world staggering and tragic gun death that occurs there. The tone and content of the game was, to put it lightly, ill-advised.

I think Watch Dogs 2 has corrected for that in some ways. The DedSec hackers of the sequel are fun-loving and cool. They make each other laugh, and there’s a real joy in how they joke with and prod at each other over some of the goofiest stuff (like tricking each other that a robot car can talk). A huge amount of that comes from the characters getting to be themselves within the context of a diverse cast.

Like you said in the Waypoint podcast a little while back, protagonist Marcus Holloway is a black man who doesn’t have to stand in for all black people; by virtue of two central characters being black, we get to see a wider range of black life. Horatio Carlin, or Ratio, is another critical DedSec character, and his and Marcus’s interactions are some of the most interesting and crucial scenes in contemporary gaming.

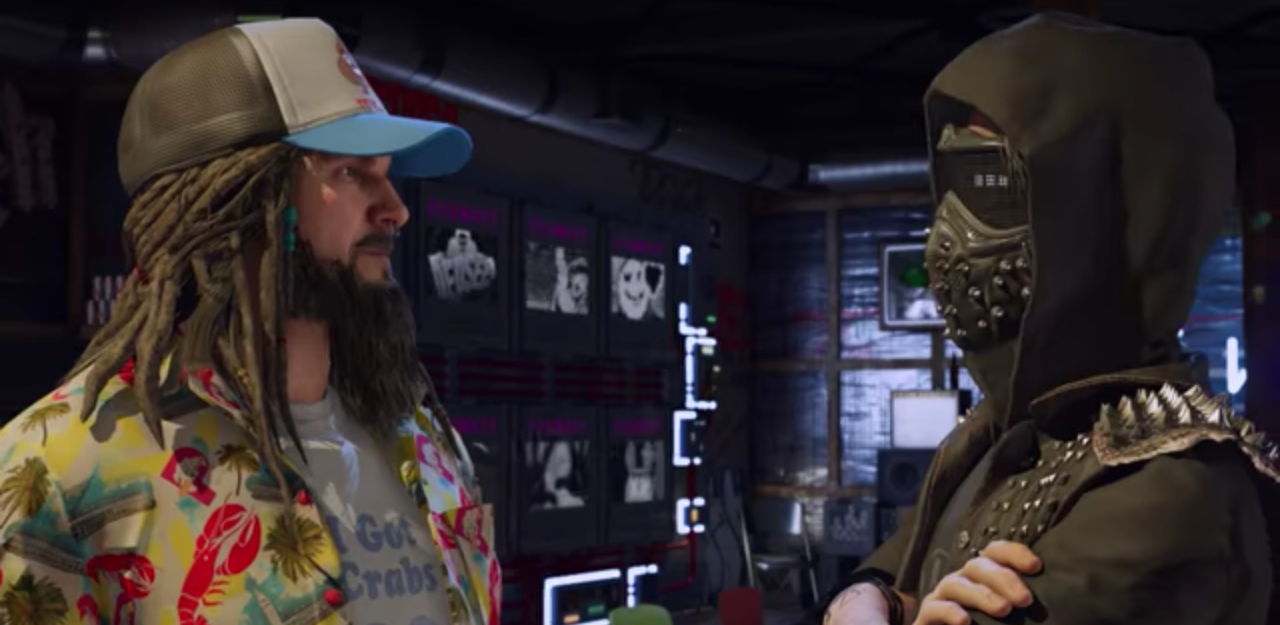

Header and all Watch Dogs 2 screens courtesy of Ubisoft

And, despite all of that, I think Watch Dogs 2 really fucks it up. You know what I’m talking about?

Yo Cameron,

I do. I know exactly when it fucks it all up. You’d given me a (spoiler-free) warning that some bad shit was coming, but when it happened I was still floored. No, wait, floored is wrong. I was disappointed. Because… well, to get into why it was so disappointing, I have to talk briefly about why things had been going so well with Horatio.

During the early portions of the game, Watch Dogs 2 communicates that it is—for better or worse—going to try to engage with questions of identity and marginalization. The catalyst for Marcus joining the do-gooder hacktivist collective called DedSec is that the crime-stopping (and privacy invading) CTOS software suite determined that he was a criminal because he fit a profile: Young, black, and in the wrong places at the wrong times.

And, as if to say “No actually, we’re really committed to talking about identity, culture, and politics in this game,” WD2 immediately highlights the diverse backgrounds of Marcus’ friends and contacts. As soon as you get to the underground makerspace that DedSec calls home, you find a set of tablet computers scattered around.

Each features an audiolog narrated by Horatio that digs into the background stories of DedSec’s diverse membership—and soon, the game adds even more characters to the mix. By the end of the game, Marcus’ allies are poor, queer, neurodivergent, black, and brown—and, sometimes, because identity is intersectional and complex, rich, white, and cis, too.

And when Watch Dogs 2 engages with these identities, it’s never didactic. It’s never a labor. When a character’s race or gender arises, it’s nearly always natural, sometimes touching, and often enjoyable in a real surface, humorous, get-you-smiling way. That’s how it starts with Horatio.

Watch Dogs 2

Over a beach party celebration, Marcus and Horatio realize that, oh shit, there’s another black hacker in the group now, and then smoothly slip into the familiar and comforting cadence of black folks talking. It’s a scene that highlights something that I think many depictions of code-switching miss: For those of us who navigate white America all day, a surprise chance to talk to other black folks is fun. They laugh and joke and talk over the heads of the rest of the crew—never derisively, but in a “this is for us” way.

Frankly, it’s also just rare to hear black people talk to each other in games. It’s part of why Franklin and Lamar stood out as joyous and playful in what could otherwise be the deeply cynical Grand Theft Auto 5. And about seven or eight hours into WD2, I was worried that it, too, was about to get cynical and toss away the cool stuff it had been doing with Marcus and Horatio, as it had become quiet on race over the last few hours.

And then it did the opposite, directly confronting the question of racism in Silicon Valley. WD2 itself code-switches.

Because this is a game about hacking, you of course eventually reach a mission where you need to sneak into WD2‘s Google-equivalent. Horatio, as it happens, works his 9-5 there. And as he steps onto the closed off campus with Horatio, Marcus is (comedically, but also sincerely) a little horrified. “Ain’t nobody look like us,” he jokes.

For Horatio, this is the everyday. “Welcome to my world. There’s only three other black people who work here,” he says. “You haven’t experienced corporate life until you’re the only brotha in a meeting and you have to represent all of blackdom. If I had a nickel for every time someone complimented me for being well spoken…” Marcus laughs. I laugh. Someone in this office called me articulate last week.

Watch Dogs 2

This mission is just fucking sharp man. It’s funny and smart and never feels like a lecture. It’s not just gallows humor, it’s a specific sort of developed, familiar gallows humor. The sort that gets built when the noose lingers in view, and on the worst days, it feels like it’s just a logistical error that it hasn’t found you yet. All of that is rolled up into the rumbling performances delivered by Ruffin Prentiss and Michael Xavier, Marcus and Ratio, respectively. It’s a high point for Watch Dogs 2, a game that, for me, had lots of high points.

And then they do it. They drop the ball. A few missions later they fucking kill Horatio. It’s not that they kill him that bugs me, though. It’s how they do. And what comes after. Or rather, what doesn’t.

Is that where it lost you too?

Hey Austin,

That’s exactly where the game lost me. Marcus walks into a room looking for Horatio. He’s laying there dead on the floor and covered in blood, and I was straight-up flabbergasted about what was happening.

The stakes of the game aren’t that serious when Marcus finds the body. DedSec is a hacking group, and they do a bunch of prankish things to show corporate America where it can shove its surveillance apparatus. It’s edgy-leaning-toward-silly, but it’s a tone that all the characters can really live in. At this stage in the game, Marcus is investigating a politician, and it’s some Socially Aware Video Games 101 all the way through.

And then, cynically and brutally, the game unravels all of the brilliant setup that it’s done around race in order to make the stakes that much more real or serious. Back in 2014, I wrote a piece for Paste where I said that the original Watch Dogs only understood women as plot points. In that game, the only engine of narrative movement was through physically hurting and emotionally wounding women in order to motivate Aiden Pearce to react. Women couldn’t be women. They could only be a stand-in for dramatic development.

Watch Dogs image courtesy of Ubisoft

All of those amazing moments that you’re describing with Marcus and Ratio were things that suggested to me that the developers of WD2 had learned something from the criticism of the original game. Video games often have a problem with understanding race, gender, sexuality, class, and other things we think of as constitutive of identity as mere traits that people have. In Gears of War, Cole is a Gear who also happens to be black, and race is treated as some kind of additional quality that has no bearing on his life.

In the scenes that you’re pointing to in WD2, the game is being super clear that being black in America means experiencing life in a very particular way. It’s about navigating lots of different contexts with lots of different strategies, some of which are joyful and others that are decidedly not.

The scene and context where Horatio dies is a moment where Watch Dogs 2 makes a choice to forget all of those interesting moments that it has shown us. The original Watch Dog‘s narrative design strategy shines through here: Horatio is used up by the game. He taught the player a lesson about race, and then he’s killed off screen to be found on the floor beside a gun. In a fit of rage, Marcus picks up the gun and storms out of the room, bound to find the gang who murdered Ratio on the orders of a low-level politician. It’s cold, and it’s bleak, and it feels like another game entirely.

The most astonishing part of it to me is what happens to those moments with Horatio after his death. They’re erased from the game, like drawings in the sand, and I don’t even think he comes up again. How did you feel about that?

Cam,

Exactly! It’s not just that the game “forgets all those interesting moments that it has shown us,” it’s that it forgets that it ever showed them to us to begin with. WD2 doesn’t only stop delving into this territory, it stops even referencing that it ever did.

I really believe there could’ve been a way for Horatio to be killed that “works.” As is, he’s kidnapped and killed by the Tezcas (a gang in WD2‘s Oakland) because he’s part of DedSec, and they… I guess I’m not really sure? They want to know some secret info that hackers know, is I think what the game is going for?

Instead, though, what we get is a boilerplate set of missions that feel ripped from the first Watch Dogs. Marcus goes from gang hideout to gang hideout “neutralizing” everyone he finds there, ruining the gang’s operations, and eventually confronting its leader. But the Tezcas are a sketch in a game filled with paintings. Where many of WD2‘s missions offer clever geometries to explore and exploit, this mission’s are indistinct (and like the first game’s faux-Cabrini-Green, they feel ripped from sensationalist depictions of “the inner city.”)

Worse, though, is that when all of this is over, it really is over. The remaining members of DedSec commiserate, arrive at an “at least we got those bastards” equilibrium, and Marcus “buries” Horatio by drilling into his private hard drive. And that’s it. Ratio is never mentioned again.

There’s no “Horatio would’ve loved to see this,” after the huge, Act 2 finale. There’s no “If only Ratio was here…” during the (otherwise really cool) moment in the final mission where the player has to take on the roles of other party members to do legwork because Marcus is compromised. Through the final moments of the game, even as the major conflict wraps up, Ratio never seems to enter Marcus’ mind. It’s like he never existed at all.

When characters die for no meaningful reason (and at the hands of something seemingly random), a work gestures towards a sort of nihilism. Like Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men, death comes for us all and sometimes there is no reason for it and no way to stop it.

Watch Dogs 2

But the bulk of Watch Dogs 2 isn’t this sort of story. It is playful and optimistic and charming and free. It’s internally inconsistent and a little naive, sure, but it seems to really, truly want to push the idea that you and I can make a difference. After all, the resounding message of DedSec isn’t “We’re going to fix America’s problems,” it’s “Everyday people could change the world if only they had the right information.”

Even in stories about nihilism, there is the possibility for a sort of optimism. “In the face of overwhelming nothingness,” the protagonists might say, “we’ll make our own meaning of the world.” If this was the sort of game Watch Dogs 2 was, Ratio wouldn’t be forgotten, he’d be the foundation on everything that comes next.

If you are on the margins of America, life can seem meaningless. When black, brown, and queer folks are killed, there is so often a two-fold tragedy: First, the death, then the forgetting. If Ubisoft really, truly felt like Horatio’s death was necessary, then he could’ve at least been another black man remembered by his community. Instead, his death makes his entire existence feel tacked on. Another disappearing body.

As Watch Dogs 2 wrapped up, I found myself thinking through the game from the top: What—besides the aforementioned level at the Google analogue—would change with Ratio’s absence? He disappears from the scenes so easily. A shadow of someone never there. In some instances, it feels like he’s a holdover from a previous version of the game. Other times it feels like he’s been patched in.

After all, the only material memorial Horatio gets are those those audiologs I mentioned. He talks about Josh and Sitara, about Marcus and Wrench, about DedSec in general. But like you said. He’s used up, devoured by the game. There’s no audiolog for Horatio.

As a fiction writer and storyteller, when I decide to kill a character (in a story that doesn’t have nihilism as its root, at least), I think a lot about a specific paragraph of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me. In that extended letter to his son, he writes:

Always remember that Trayvon Martin was a boy, that Tamir Rice was a particular boy, that Jordan Davis was a boy, like you. When you hear these names think of all the wealth poured into them. Think of the gasoline expended, the treads worn carting him to football games, basketball tournaments, and Little League. Think of the time spent regulating sleepovers. Think of the surprise birthday parties, the day care, and the reference checks on babysitters. Think of checks written for family photos. Think of soccer balls, science kits, chemistry sets, racetracks, and model trains. Think of all the embraces, all the private jokes, customs, greetings, names, dreams, all the shared knowledge and capacity of a black family injected into that vessel of flesh and bone. And think of how that vessel was taken, shattered on the concrete, and all its holy contents, all that had gone into each of them, was sent flowing back to the earth.

Games, for their sprawling scale, have historically been a “tight” medium when it comes to characterization. There is not room (or budget) to show the soccer balls and science kits, the embraces and private jokes. Yet Watch Dogs 2 finds the time for those. The quick, knowing glances. The personal assurances. The little sketches of humanity that elevate it so high above the first game in the series. But for Horatio, all of that is not only shattered on the concrete, but the ash inside swept under the rug and ignored. No one, it seems, remembers that Horatio was a particular boy.

But I so want to be wrong. In my fanon (apologies, Frantz), Marcus is biting his tongue for the entire final third of the game. Now he is the only brotha in the meeting who has to represent all of blackdom. Who else in DedSec understands Horatio’s death like him? How can he share the weight of his grief?

As he enters Blume HQ during the game’s final mission, Marcus hypes himself up by singing a Danny Brown’s lyric on the group’s voice chat: “Got the game the game on lock like we changed the key!” DedSec is confused. “Huh? Who” No one recognizes Brown’s high speed cadence or playful lyricism. Maybe, I imagine Marcus thinking to himself, Horatio would’ve.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshot: Grinding Gear Games -

Screenshot: Audible -

Screenshot: Sony Interactive Entertainment