Way back in 2003, I coauthored a book that made this full-throated defense of pre-workout stretching: “[W]hen athletes stretch diligently and rigorously, they train better, perform better, recover faster, and over the long haul, suffer fewer chronic and debilitating injuries.”

That was the opinion of Ian King, my coauthor, who at that time was about as well-known and well-regarded as a strength coach could possibly be. By the early 2000s he’d trained elite athletes on four continents, including Olympic gold medalists and world champions in a long list of sports. It’s what world-class athletes did back then; they stretched before they trained or competed, and who could argue with the results?

Videos by VICE

It’s a rhetorical question, of course. Spend enough time with strength and conditioning professionals, and you’ll realize that the best athletes aren’t necessarily the best because of their training methods. Sometimes, they win despite their programs.

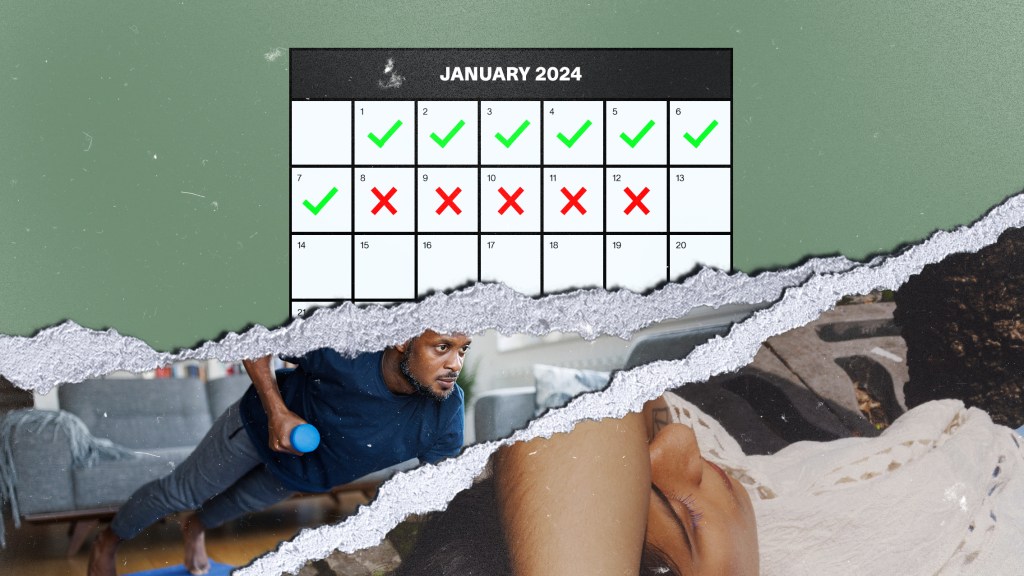

In fact, lots of researchers, coaches, and trainers had begun to doubt the benefits of static stretching—getting into a muscle-lengthening position and holding it—by the time my book with Ian came out. Researchers discovered that pre-competition stretches reduced explosive power for up to 40 minutes. Coaches were starting to use more dynamic pre-workout exercises, saving the static stretches for the end of the training session. And trainers realized their clients could get equal or better results without a bunch of exercises they hated anyway.

But like everything in fitness, what goes out of fashion eventually comes back. My return to pre-workout stretching started with a knee injury that refused to get better. I asked my friend Chad Waterbury, a neurophysiologist and doctor of physical therapy who lectures organizations like the National Strength and Conditioning Association, for some advice. He recommended a three-minute hamstring stretch. For each leg. That’s six minutes of static stretching for one set of muscles.

I quickly realized the long hamstring stretches worked even better if I paired them with static exercises for my quads. And just like that, I was back to doing extensive pre-workout stretching.

More from Tonic:

Which made me wonder: Was the conventional wisdom right? Did we overreact to research on competitive athletes, whose needs and goals aren’t anything like ours? “The reason we’re still debating is because the research is all over the place,” Waterbury says.

For the average man or woman working out in a gym, research shows static stretching will probably reduce your maximum strength on an exercise like the squat. “But who cares if your strength decreases by some small percent?” Waterbury says. “It’s going to be irrelevant.” Your results will depend on the absolute effort you put in, not the amount of weight you lift.

The more important question, he adds, is why your muscles feel stiff in the first place. “Protective tension is there because the brain is trying to prevent an injury,” he says. The brain tenses muscles for one of two reasons: to protect an unstable joint above or below the tight area, or because another muscle isn’t doing its job. So if you can’t effectively activate your glutes on a squat or deadlift, stiff hamstrings could be your body’s way of compensating.

That brings us to the long-held notion that stretching prevents injuries. It assumes that protective tension is the problem, rather than your brain’s way of avoiding a problem. To your brain, stiff hamstrings are better than a herniated spinal disc. So, logically, stretching that tension away won’t have any effect on your injury risk because the underlying issue is still there. That’s why, Waterbury says, “the vast majority of research shows it has no protective effect against injury.”

For most people, most of the time, the best way to warm up before a workout is to actually warm up. That is, do a few minutes of continuous exercise—burpees, jumping jacks, rowing—to increase your core temperature slightly, do some kind of stretching sequence to make sure your joints have an optimal range of motion, and then prepare for specific exercises with at least one warmup set using a lighter weight.

Waterbury prefers dynamic pre-workout stretches over static ones—30 seconds of arm circles instead of an extended shoulder stretch, for example, or 30 seconds of walking leg kicks instead of holding a hamstring stretch for the same amount of time. And then, ideally, you’d do static stretches at the end of the workout, when your muscles are warm and properly activated and, perhaps, less restricted by protective tension.

Whenever you choose to do static stretches, there are two good ways to make them more effective:

Hold for at least 30 seconds, but preferably longer. “It’s like low-intensity cardio,” he says. “It’s boring as hell, but the longer you hold the stretch, the better. It’s whatever your time and patience allow.”

Once you’re in the stretched position, take a deep breath. Imagine that you’re pulling the air all the way down into the targeted muscle. You should feel the range of motion increase, a sign your brain is releasing some tension.

The real key to the before-or-after question, Waterbury says, is what works best for you. “If you feel better when you stretch before a lift, you should absolutely do that.”

Read This Next: Why Working Out Makes You Want to Drink