As the Russian invasion of Ukraine grinds on and tensions rise between the U.S. and China, the specter of new hypersonic weapons looms larger. These are super-fast and maneuverable missiles that can be nuclear-armed, and which Russia, China, and the U.S. are all racing to develop and deploy. Putin and the media have previously described them as “invincible” and “unstoppable” by modern anti-missile systems.

But what makes a weapon hypersonic, why does everyone seem to want them, and are they really all they’re cracked up to be?

Videos by VICE

Ukraine has already claimed to have shot down Russia’s hypersonic missiles. According to the Ukrainian Air Force, it used an MIM-104 Patriot missile system to intercept a Russian Kh-47 Kinzhal, an air-launched hypersonic ballistic missile, on May 6. Ten days later it said it shot down more of the “unstoppable” weapons.

Moscow fired a barrage of six of these advanced hypersonic weapons at Ukraine in March. At the time, Kyiv said it couldn’t shoot them down because of their speed and maneuverability. The recent destruction of the missiles suggests they aren’t as unstoppable as Moscow wants the world to believe. Using a U.S. missile system first deployed in the 1980s (and since upgraded), Kyiv said it destroyed the Kh-47 Kinzhal—“Dagger” in Russian—and poked a major hole in the narrative about hypersonic weapons generally and the Kinzhal specifically.

The hype around these weapons is driving a new arms race. China has tested two new hypersonic missiles, Russia is using them in Ukraine, and the Pentagon has told Congress it’s playing catch-up. These weapons—and the misinformation surrounding them—will shape warfare for years to come, and here is everything you need to know about them.

What is a hypersonic weapon?

The term “hypersonic” has been used and abused in recent years. Technically, any object that’s traveling at five times greater than the speed of sound is traveling at hypersonic speeds. Today, the term is meant to hype up a new class of weapons that militaries promise will devastate their enemy. New hypersonic weapons are meant to be both fast and maneuverable. Russia’s Kinzhal and China’s Dongfeng-27 are two recent examples that have made headlines.

The “glide” capabilities of the various hypersonic missiles is an important part of the hype around them. The idea is that the weapons can travel more than five times the speed of sound while also retaining their ability to out-maneuver missile defense systems like the Patriot. It’s also possible that existing systems meant to alert the military to a nuclear ICBM launch might not be able to see them in time to respond, altering the delicate balancing act of deterrence, which requires nations to be able to counterstrike while nuclear missiles are in the air.

The Kinzhal’s shot down in Ukraine were supposedly hypersonic, but couldn’t glide. But Russia has developed, it claims, hypersonic weapons that can glide.

Typically a missile is either fast or maneuverable, and this idea that some hypersonic missiles can do both (as is the case with Russia and China’s missiles) or will be able to do both (which is what the Pentagon’s various projects claim) represents an ideal weapon. One that may not actually exist.

“Weapon development is all about trade-offs,” James Acton, the co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told Motherboard. “You ideally want a weapon with really, really long range that is superfast, highly maneuverable, and can carry a massive payload. But in the real world, you can’t get all of those things at once. So weapon designers always have to make trade-offs. What I think is true is that boost-glide technology, and to a lesser extent hypersonic cruise missile technology, is reducing the need to make those trade-offs.”

According to Acton, the real advancement of hypersonic weapons is the reduction of these trade-offs. He also noted that hypersonic weapons aren’t, in and of themselves, a new technology. “So there really is a development here, but there’s no hard cut off,” he said. “There’s no bright red line going on here. There’s nothing like there’s no obvious dividing line between old fashioned weapons and the new hypersonic weapons.”

Acton noted that Top Gun Maverick opens with Tom Cruise ejecting from a jet while flying at high speeds. “The idea of stuff traveling five times faster than the speed of sound is the stuff of Hollywood movies,” he said. “There is something about high speeds that have always captivated people. And a lot of the hype around hypersonics kind of ignores that speed, in and of itself, is not really new,” he said.

The phrase “hypersonic weapons” covers a lot of territory and sounds like a flashy new term. The truth is that hypersonics have been around for decades. The nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) fielded by Russia, China, and the U.S. all fly at hypersonic speeds and the technology that underpins hypersonics—boost-glide—is as old as World War II.

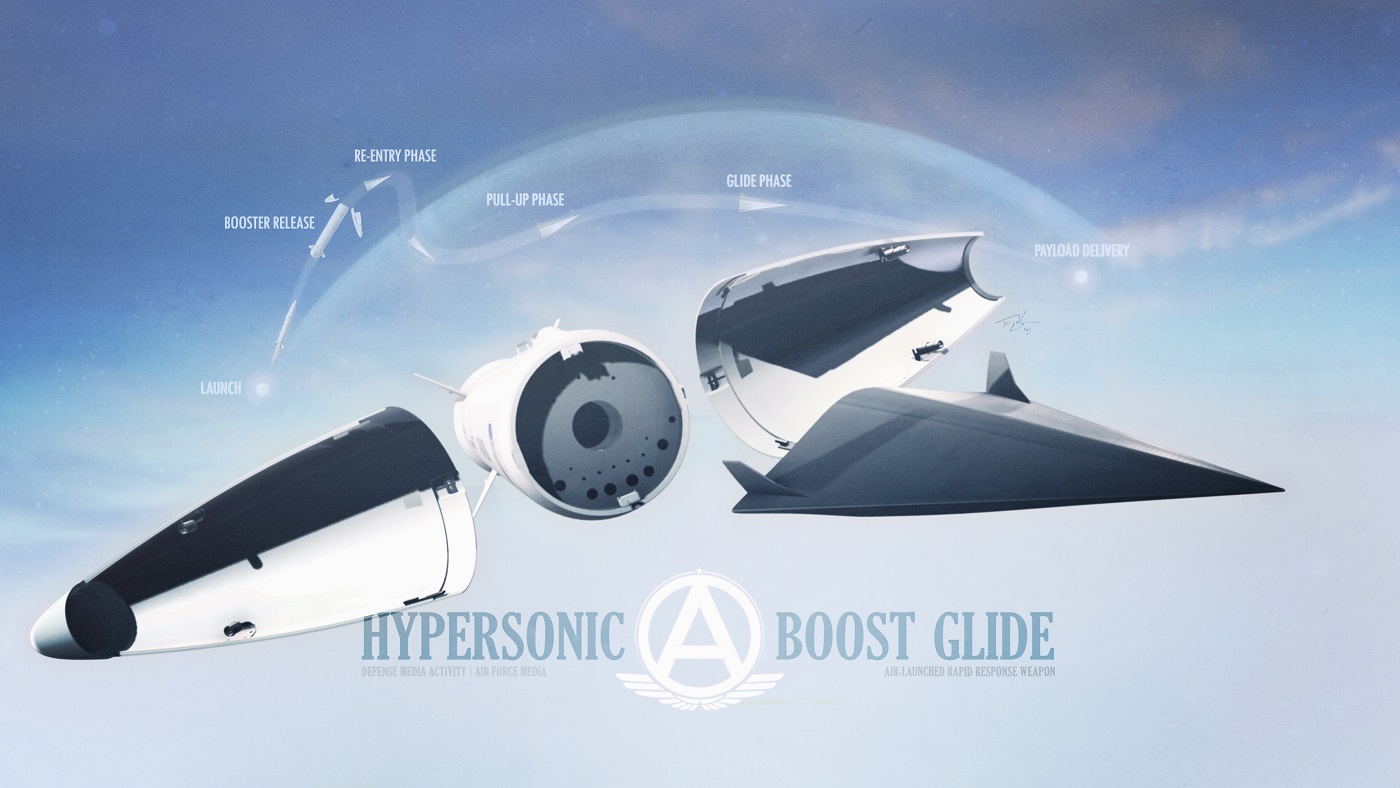

But when people talk about modern hypersonic weapons, they’re usually talking about boost glide technology, not necessarily new methods of propulsion. The idea is that the new glide capabilities will allow missiles to maneuver past missile defense systems and possibly remain undetected by radar.

“A boost glide system is launched by a large rocket, just like a conventional ballistic missile,” Acton said. “What a ballistic missile does is it arcs high above the atmosphere, and falls exclusively under gravity until the very end when it re enters the atmosphere.”

“A boost glide system is the same kind of rocket launch booster, but it’s fired on a much flatter trajectory,” he said. “So the glider re-enters the atmosphere much sooner. And it’s then supported by aerodynamic lift. So these things are not powered throughout their flight, like cruise missiles, they’re only powered during the boost phase. But they’re boosted up to a very high speed and then aerodynamic lift keeps them aloft for you know, potentially 10 or 20,000 kilometers in the very longest case…it’s the same physics or that is the same basic principle as a hang glider, but just much, much, much higher speeds.”

Are hypersonic weapons as game-changing as militaries claim?

At the heart of this race is the persistent threat of nuclear weapons. The U.S, China, and Russia all possess nuclear weapons capable of destroying the other countries. No one nation nukes another because they know that the enemy might see it, and retaliate with their own. Firing the first nuclear weapon is a death sentence.

But the U.S. has, for decades, pursued defense systems that will alert it quickly and—possibly—shoot Russia or China’s nuclear weapons out of the sky. That upset the balance. In response, Russia and China are developing weapons that fly faster and avoid missile defenses. They may not beat America’s defenses entirely, but faster weapons would reduce the amount of time the U.S. has to respond to attack.

But what Russia and China say they have in terms of hypersonic capabilities and the reality of what is going on may be two different things.

“As somebody who lives fairly close to the Pentagon, I’m entirely indifferent as to whether I’m killed in a nuclear war by an ICBM or a hypersonic glider.”

“This thing has reached its most ridiculous state with the Kinzhal, which is a Russian air-launched ballistic missile that appears to be almost identical to the Iskander ground-launched ballistic missile,” Acton said. “Nobody called the Iskander a hypersonic weapon but people take Kinzhal as being a hypersonic weapon. Either both of them are hypersonic or neither of them are hypersonic, but you can’t put them in different categories. There’s a lot of linguistic confusion and hype and Russian manipulation in all of this.”

The May 16 volley of missiles Moscow fired at Ukraine contained both Kinzhals and Iskanders. According to Kyiv’s military head, Valeriy Zaluzhnyi, Ukraine intercepted six aircraft launched Kinzhals, nine ship-launched Kaliber cruise missiles and three land-launched Iskanders. The Kinzhals don’t glide or use any other advanced boosting technology. They just fly fast enough to be considered “hypersonic.”

Acton said he was not, particularly, worried about hypersonic nuclear weapons. Standard-issue nuclear missiles are fearsome enough, and the effectiveness of current interception methods is overblown.

“Russia can already annihilate the United States with nuclear weapons,” Acton said. “Russia has hundreds of ICBMs. Our missile defenses cannot and, indeed, are not designed to stop Russian ICBMs because it’s impossible. As somebody who lives fairly close to the Pentagon, I’m entirely indifferent as to whether I’m killed in a nuclear war by an ICBM or a hypersonic glider.”

Acton has hit on something outside of knowledgeable defense circles: missile defense is a crapshoot that often only works under optimal conditions. To defend against ICBMs being shot at the homeland, the U.S. relies on an assorted number of ground and sea-based missile defense systems. The basic concept is that a series of radar stations on the ground and sensors in space would detect a fast moving missile and the defense systems would intercept the threat and destroy it before it hits its target.

“If you ask the general public, ‘Do we protect America from missile attack?’ They would say, ‘Yes.’ They would think we have a missile defense. We do not. We should be absolutely clear, we do not have a system that can protect the United States from even a limited ballistic missile attack. It just doesn’t work.”

“If you ask the general public, ‘Do we protect America from missile attack?’ They would say, ‘Yes.’ They would think we have a missile defense. We do not. We should be absolutely clear, we do not have a system that can protect the United States from even a limited ballistic missile attack. It just doesn’t work. We don’t have it, we’re very unlikely to have it, we are probably never going to have it,” Joseph Cirincione told Motherboard.

Cirincione is a national security expert with a long pedigree. He’s retired president of the Ploughshares Fund, the former director of non-proliferation at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and was a staffer for Congress for 9 years where he worked on military reform. Among other things, he investigated missile systems and nuclear weapons. “Even in perfectly scripted tests, they’re only 50% effective, not something you would want to base the defense of a country on,” he said.

Cirincione said that the U.S. only conducts staged tests of its missile-detection capabilities. “Can the radars of the missile see the warhead? Can the interceptor be guided into an intercept path successfully? Can it actually hit? To do that, you sort of stage the tests so that the defender knows exactly when the target is going to be launched, what the target looks like, what its radar signature infrared signature is going to be,” he said. “In some cases, we’ve put a radio transponder on the warhead that was sending out a here I am signal so that the interceptor could just ride that into it…we have never done a truly operational test to try to see if the interceptor can hit a target when the target is trying not to be hit.”

Attempting to intercept an ICBM in flight is like trying to shoot a bullet with a bullet when both bullets are flying upwards of 24,000 miles an hour. “It’s amazing, we can do it at all,” Cirincione said. “This is a technological achievement that 50% of the time, granted under perfect conditions, we can hit a bullet with a bullet. That’s amazing. Unfortunately, it’s just not good enough. In thermonuclear war ‘almost’ doesn’t count. You’ve got to defend 100% of the targets 100% of the time.”

How close are the U.S., China, and Russia to developing a hypersonic weapon?

According to Acton, nations have been trying to develop some kind of hypersonic boost glide weapon since the Cold War. Development of the weapons go in and out of style, but never quite leave the military’s consciousness. He said the current hype cycle around hypersonics began during the War on Terror.

“The Bush administration in 2003 made a big push for hypersonic weapons which fell short of its very, very, very ambitious original goals,” he said.

This was the Force Application and Launch from CONtinental United States (Falcon), a joint venture between DARPA and the U.S. Air Force. The plan was to create a launch vehicle that would push payloads into orbit where they would then skip across the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds before returning to Earth. Early concept renders made it look like a guitar pic. Two test flights in 2010 and 2011 had mixed results and, though technically still in active development, other hypersonic weapon projects in the U.S. now receive more attention.

According to Acton, the Falcon spooked Russia. It began to develop its own hypersonic weapons, partially in response to what it perceived as a threat from the U.S. In March of 2018, Putin revealed them to the world. During his speech, the Russian president announced six new weapons. One was the RS-28 Sarmat, what NATO calls the “Satan II,” which would fly at hypersonic speeds (it’s an ICBM after all) and could deploy up to 24 nuclear tipped Avangard hypersonic glide vehicles. Putin demonstrated the supposed capabilities of these new weapons by playing a video of the weapon destroying Mar-a-Lago.

Aside from its traditional ICBMs, which already travel at hypersonic speeds, America has still not deployed its own hypersonic-capable weapons. During recent testimony before the House Armed Services Committee, Paul Freisthler, the chief scientist at the Defense Intelligence Agency’s Directorate for Analysis, told Congress that hypersonic weapons were a pressing threat to the United States. “Amid the backdrop of strategic competition, the events of the past several years demonstrate in no uncertain terms that our competitors are developing capabilities aimed to hold the U.S. homeland at risk,” he said.

Despite this pressing need from politicians and the Pentagon and years of development, America can’t seem to produce a hypersonic weapon worth a damn. In March, the U.S. Air Force canceled the AGM-183, an air- launched missile that was set to be America’s first new hypersonic weapon. The AGM-183 had a long and troubled development culminating in a failed test launch on March 13.

But the U.S. still has more than a half dozen other hypersonic weapons programs in various stages of development at various branches of the military. The Air Force is working on a Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, the Army has a Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, and the Navy is working on a Hypersonic Air-Launched Offensive Anti-Surface Warfare cruise missile. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is also working on several hypersonic programs.

The U.S. has also made strides in hypersonic weapons that simply go faster with less fuel. The Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC), is a kind of ballistic missile that fuels itself, in part, by drawing air from the atmosphere. The U.S. successfully tested one of these in January.

According to Freisthler and others, America is lagging behind on this new and vital technology despite all the programs. “China is pursuing an intercontinental-ballistic missile with a hypersonic glide vehicle payload and has conducted several flight tests since 2014, including a test in July 2021 that circumnavigated the globe,” he told Congress.

China may have deployed a version of its hypersonics, the DF-17. According to leaked Pentagon reports, it’s also successfully test fired and upgraded DF-27. A DoD report from 2021 said this new missile could fly almost 5,000 miles at hypersonic speeds before using a “hypersonic glide” to evade anti-missile systems and hit a target. It’s also developing the DF-41, a long-range nuclear weapon with a glide vehicle.

“Experts assert that this type of system might provide China with the ability to launch hypersonic glide vehicles over the South Pole, thus evading U.S. early warning assets that track threats over the North Pole and further reducing the amount of warning time prior to a strike,” a 2022 report to Congress on hypersonic glide vehicles said.

Are hypersonic weapons inevitable?

The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, which George W. Bush withdrew the U.S. from, once limited the amount of missile defenses every country could have. “As a matter of policy the U.S. has, for decades, not tried to design or develop missile defenses to undermine China or Russia’s nuclear arsenals,” Acton said. “We try to deter nuclear attack against the homeland from those states, we don’t try to defeat that attack. The same is not true with North Korea. You know, the U.S. does develop missile defenses to try to intercept North Korean ICBMs. It is just stated policy, even under the Trump administration, we do not try to develop missile defenses to intercept Chinese or Russian ICBMs. And the reason is, because we can’t.”

Acton said he was skeptical that the U.S. could defend itself against North Korea’s nuclear ICBMs. “Unfortunately, my money would be on North Korean ICBMs, not on our defense,” Acton said. “It’s not in terms of what I would want to happen, obviously, but in terms of who I think would win that contest. So it is entirely infeasible for us to defend ourselves against Russia and China. And, you know, any prospect we might succeed would lead them to massively build up their nuclear arsenal, which is in fact exactly what has happened, right?”

Another byproduct of this arms race, America’s withdrawal from various treaties, and its gloating about advanced weaponry has been China and Russia’s pursuit of hypersonic weapons. “I think people generally underrate U.S. capabilities in this area,” Acton said. The Pentagon’s Bush and Obama-era projects had an ambitious goal: the development of an highly accurate, non-nuclear armed intercontinental missile.

“It’s the hardest thing you can possibly do,” Acton said. “And the U.S. struggled with that because it is the hardest thing imaginable. So, in some sense, the U.S. was running a very different race from Russia and China for a very long time.”

In the back half of the Obama administration, the Pentagon shifted its focus to developing hypersonic weapons similar to what Russia claims to have deployed, and what China is testing. “I believe, somewhat heretically, that U.S. hypersonic capabilities are almost certainly better than Russian hypersonic capabilities.”

Russia has said it’s deployed several of the weapons, and the only ones it’s used in combat have been reportedly shot down by Ukrianians using U.S. tech. China, in publicly observed tests, has successfully launched several of the weapons. America’s focus, right now, is on conventional warheads flying faster than five times the speed of sound. Tests have had mixed results.

Cirincione said that the U.S. didn’t need the tech because it’s basically already won the race. “We have basically got [Russia] surrounded. We have a vast military alliance system, both in Asia and Europe. We’ve got them completely outgunned. We don’t need hypersonics.”

China, he said, had a different set of concerns. “So if you’re China, what’s your problem? Your problem is that the U.S. Navy basically has a cordon around your nation, you can’t break out if the U.S. Seventh Fleet is there blocking you or threatening you and doing patrols off your coast,” he said. “I mean, how would we feel if the Chinese navy were off of Long Island, you know, we’d want to develop a system that could push them back.” Hence, he said, a focus on developing hypersonic capabilities that might counter U.S. aircraft carriers.

Cirincione said that the reason there’s so much fear in the Pentagon and at Congress about the weapons is because it’s good for business. “Most of the reason we’re pursuing [hypersonic] weapons is not because the threat we face demands it,” he said. “It’s because the defense contractors that provide us our weapons have the ability to do it, and they can make money off doing it.”

Kyiv claimed it shot down six of Russia’s advanced hypersonic weapons using a Patriot missile system. During the first Gulf War, the Pentagon claimed that the Patriot was fantastic at intercepting Iraqi missile attacks. President Bush said it hit 41 out of 42 Scuds. “That turned out to be wrong. It was a lie,” Cirincione said.

Cirincione was part of a Congressional investigation into the Patriot system at the time. “We found that it had hit between zero and four of the Scuds that were fired.”

But that didn’t mean the other scuds hit their target. Some broke apart in mid-air, others missed their target completely. According to Cirincione, the U.S. Army misinterpreted a lot of data about what the patriot system could and couldn’t do at the time.

The Patriot system Ukraine used is more advanced than the ones used by the Army during the Gulf War. It’s possible that Kyiv shot down some, or even all of the missiles. It’s equally possible that Russia’s “hypersonic” missiles—which are old missiles with some upgrades—broke apart in the air or failed to hit their target.

When it comes to hypersonic weapons and missile defenses, it’s hard to know what the truth is until long after the missiles have flown and the interceptors fired.

Update 6/1/23: The original version of this article said that Bush claimed the Patriot hit “41 out of 44” Scuds. This is incorrect. The stat has been updated.

More

From VICE

-

Kelvin Murray/Getty Images -

Yulia Reznikov/Getty Images -

Illustration by Reesa -

Screenshot: Peacock