Rey Flemings likes to say that he is two degrees of separation from any significant gatekeeper in the world, one of a few reasons why he is so good at getting the richest people in the world whatever their hearts desire.

Take, just for example’s sake, the $1 million house party he put together for a client who had recently moved to Miami and wanted to make a splash during Art Basel; Flemings secured, in a matter of days, a few pieces from the Smithsonian and an agreement with the U.S. Coast Guard to shut down the waterway so that guests, including three heads of state, could pass through by ship. Or maybe consider the time he helped protect one of his clients with armed private security in a country where doing so is usually illegal by convincing the government to “secure an American private citizen like a diplomat,” even having a member of the president’s own security detail help out. Or what about the NBA-style COVID bubble he successfully established at a Mexican private villa in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, which included a traveling party of roughly a dozen people and many dozens of staff, entertainers, and chefs? (Price tag: approximately $900,000.)

Videos by VICE

If there is one person in the world who has figured out how the upper crust of society works—its unwritten rules, language, and particulars—it might just be Flemings. Over the last decade, he has become one of the premiere fixers for the global elite, a Jeeves-like magician who professes to be able to make the wildest dreams of some of the richest people in the world come true. He can get clients into locker rooms, secure them private hospital wings during a pandemic, and help get them into most exclusive places in the world, like the Met Gala, highly anticipated Saturday Night Live performances, or on the field during the Super Bowl.

More than that, though, Flemings gives the fantastically rich a private place to admit what they can’t say publicly: that their extravagant life is not as fulfilling as they had hoped it would be, and that they need help figuring out how to fix it.

“Nobody wants to cry for rich people and the 1 percent, but it is an odd, lonely world,” one of Flemings’ billionaire clients told me.

That is where Flemings comes in, offering, as his client put it, an opportunity “to live a more interesting life.” One of the first things Flemings does when he signs a new client is ask them to provide answers to approximately 150 questions. The list, which is regularly updated and tailored to the individual client, is broken down into approximately distinct sections like “Legacy,” “Private Medical,” Security & Risk,” “Public Relations & Brand Building,” “Matchmaking,” and, of course, “Yachts.” Some of the questions are of the more standard variety. What is your net worth? Where are your homes located? Are you interested in purchasing a plane?

But the crux of the exercise is to obtain a deeper knowledge of the client’s wants and desires. Are you happy? Are you happy with the public’s perception of you? Your doctor says you have one year to live, what do you do? If it’s different than what you’re already doing—why?

The questions are an attempt to start finding a solution to the emptiness the rich can feel inside themselves. For a growing number, step one is to call Rey Flemings.

Fleming’s clients are not merely wealthy. His small and relatively unknown company, Myria, only accepts ultra-high net worth customers, defined as those worth more than $30 million. “This isn’t the 1 percent. This is the .003 percent,” Flemings said. To join, potential customers must willingly spend an average of $1 million on their “lifestyle” alone each year, and they must be enthusiastic about donation-based philanthropy as well. The select few who have made the cut include A-list celebrities, star athletes, CEOs, and founders, none of whom I’m allowed to name publicly, but who often operate in and around Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood. Flemings notes that there are almost 80 million members of the 1 percent globally, but only a few hundred thousand, at most, would be able to join Myria.

Even that might be overstating it. The name, Myria, comes from an obsolete metric prefix meant to indicate factors of 10,000, and serves as a reminder to Flemings to focus on the needs of “the top 10,000 people in the world” and no one else. “We cannot do what we do for everyone,” he said.

In the world Flemings operates in, the traditional rules of supply and demand do not apply. Indeed, they are often inverted: As the value of something goes up, so, too, does the demand for it. Such items are known, in strict economic parlance, as Veblen goods. The unorthodox rules apply only to the scarcest items, which Flemings describes as fitting one of three boxes: “the first, the best, the only.” Another way to say it is that Flemings focuses on the sort of homes that aren’t available on Airbnb, the sort of tickets that aren’t on Ticketmaster, the sort of businesses that don’t need to be on Yelp, and the sort of people who don’t need to be on LinkedIn. According to Flemings, the available services run the gamut and have included, for example, obtaining an original copy of Facebook’s little red book, which the company handed out to employees early on and became a part of Silicon Valley lore, or helping clients gain immediate access to the top medical professionals in the world when disaster strikes for a loved one.

“Gaining access to world class medical assistance is not always a straightforward proposition,” he said.

Flemings himself first started to help the rich navigate the world around them by accident, when, almost a decade ago, he got a call from a founder who needed some help. This founder had sold his company to Amazon and wanted to go on a long summer vacation in Europe to celebrate. But a previous trip had left him frustrated, unable to shake the feeling he was constantly overcharged and being made to look like a fool. At the time, Flemings was building a mobile video application, but in a past life, he had worked in close proximity to entertainment stars like Justin Timberlake. Among other tasks, he helped plan extravagant traveling parties. The founder asked Flemings he could help him plan something similar.

In a bit of unspoken favor-trading, Flemings agreed, thinking that if he did a good job, the founder might invest in his startup. A few months later, Flemings sent the founder on a Spanish vacation that was produced and fine-tuned as if it were a global tour. The plan to have the founder invest failed—“No one wants to look at your mobile video application while they’re having fun in Ibiza,” said Flemings—but it was a fortuitous moment nonetheless. Word started to travel that Flemings not only could be trusted, but could pull off world-class experiences. The rich started to reach out to Flemings with requests and he kept doing the favors in hopes of obtaining investors, only realizing six months in that the business opportunity in front of him wasn’t in mobile video, but in making the rich happier.

In September 2016, he launched a luxury concierge for the super rich—or, as Flemings puts it, the “super successful.” He called it The Blue, after the iconic “Blue Marble” photograph of the Earth, which was meant to indicate that Flemings could give clients the “access to the best of everything,” anywhere in the world. He was determined to develop the company into something with broader offerings than a luxury travel service—an organization equally as willing to help manage a public-relations crisis as it was to figure out a way to make someone’s kids happy. In time, Flemings would come to service 80 clients worth a combined $400 billion, and Flemings would become a sort of market-maker for the rich—able to serve as the trusted conduit between the people who hold the valuable resources, and the wealthy people who want them.

Flemings’ pitch to the hyper-rich begins by extending them something they don’t normally receive: empathy. Being rich is hard work, Flemings explained to me on one of our many calls this year, and it is perfectly fine to struggle with the responsibilities and stressors that come with it.

“The more successful you become,” Flemings said, “the fewer people you can trust. The more successful, the less the public thinks of you; billionaire has become a pejorative word. The more successful you become, the harder it is to find someone who will look you in the face and tell you the truth.”

Consider for a moment, Flemings asks me, the practicalities of having more money than you know what to do with. “When you’re super successful, it’s very hard to find people that you can trust,” said Flemings. “Everybody wants to sell something to the richest people in the world.” That includes diamond dealers, celebrity stylists, and yacht operators, of course, but also grifters, scammers, con artists, and anyone else desperate (or confident) enough to try their hand at bilking the .003 percent. As a result, attempting to figure out what price to pay, and how to limit liability, contractually or otherwise, can prove difficult, even maddening.

That lack of trust is where Flemings has found his niche, making the richest people in the world feel both happy and in safe hands.

To Flemings, the concept that the world’s richest people are conspiring together to rig the game in their favor seems foolish. He believes the closest the rich have come to assembling as an illuminati-like clan is in St. Barts between Christmas and New Year’s Eve, because he’s been there.

“I gotta tell you, some of the richest people in the world are struggling to talk to a girl,” he said. “There is no way these people are leading some fucking global conspiracy.”

Perhaps, but Flemings also told me repeatedly that a central “value of the network” is in the intangible interconnections it has created and fortified between the rich, the well-connected, and the powerful in numerous industries. Such knock-on network effects from a curated community of hyper-elites afford numerous benefits, some obvious and some not.

“Ultimately, connection comes from people who share your problems,” the billionaire client said. “Being able to connect with people who share those problems, I think, is valuable.”

The benefits can be even more tangible than that. One member offered their private jet to others at cost, so long as they cover the fuel and pilot’s pay, after having less time to use it once his wife got pregnant. Other members have hosted events or dinner parties, or offered season tickets to top teams, access to top private clubs, or a vacation home too nice to list on Airbnb. (“When you have an $80 million house with $100 million in decor on your wall,” said Flemings, “you’re not renting it out to complete strangers on the internet.”)

The community can even be lifesaving. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Flemings received “advanced notice” about the impending severity of the crisis from Yale professor and physician Nicholas Christakis, a compensated advisor to Flemings’ companies, which allowed his company to prepare early. By January, the company had sent an email to clients warning them that “the world would be shutting down,” then prepared COVID-19 kits with everything they needed and set up a Bay Area service where doctors would make house calls to clients. His clients were incredibly concerned they would not have “access to health care,” so Flemings also was able to successfully “privatize” the small wing of a hospital that could be set up for “emergency care.” For the favor, Flemings brokered a “large contribution” to the hospital, he said.

The community helps Flemings, too. One Tuesday this March, Flemings received word that Silicon Valley Bank was in trouble. The bank, a long-time partner of the technology and venture industry, was dealing with liquidity concerns after a series of bad bets on mortgage bonds, and the person on the other end of the line advised Flemings to pull his money as soon as he could. By Thursday, the bank run was in full swing, but Flemings was safe.

Flemings became comfortable winning over people far more wealthy and powerful than him at a young age.

The son of a single school teacher, he grew up in Memphis, Tennessee. After a brief stint at the University of Tennessee in the early 1990s, he found a mentor in a man named Richard Thomas, who ran a financial services company in Memphis. Thomas asked Flemings to start giving computer-based presentations to large financial clients. Suddenly, Flemings, a young Black man from humble origins, found himself making presentations to some of the richest people in the southeast. The presentations helped him become comfortable around wealthy people. He learned, he told me, how to form ideas and express them to the rich, and started to cultivate a network.

From there, Flemings began a circuitous path, moving to Austin and joining the early startup scene, before returning to Tennessee to head a Memphis music foundation that was part of a broader economic development initiative spearheaded by the CEOs of large employers in Tennessee. Some of the most famous members of the Tennessee music scene were involved, including Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Records, and Three 6 Mafia. So was pop star Justin Timberlake, a Memphis native. Soon enough, Flemings had joined Timberlake’s family office, which opened him up to work with others in the entertainment industry. While many family offices are primarily focused on turning a dollar into $1.03, the entertainers had heavy service needs. Flemings helped plan traveling parties and met global tour managers. Eventually, he found his way back to tech, serving as CEO for a startup called Particle, which was acquired by Apple, and founding another startup focused on mobile video.

By the time Flemings got the call from the founder that would push him into the concierge business, he had developed a uniquely diverse rolodex. He felt as comfortable with Three 6 Mafia as he did with the CEOs of tech titans. “I was one of the few people who could walk between those worlds,” he said. In this regard, Flemings is especially convincing. In conversation, he is charismatic, focused, alert, and in control. It could feel at times when we spoke like he was simultaneously pitching me as he would an investor while listening intently to my every word, as if I was his best (and maybe only) friend.

To some, the world that the super-rich occupy can feel like a complex place. But Flemings’ talent boils down to an ability to figure out who society’s true gatekeepers are and an uncanny ability to cultivate relationships with all of them. “My philosophy is that the entire world and everything in it is gated by a human,” he said. If you can figure out who controls a certain gate and then woo them, the gate can be opened. In Flemings’ experience, gatekeepers can be government officials, politicians, A-list stars, one of Flemings’ own clients, or some combination thereof.

These people, be they world-class stylists, matchmakers, or the Golden State Warriors, have become the lifeblood of Flemings’ new business, and he does everything he can to cultivate the relationships. “We have to protect our relationships with the businesses and the brands that control access,” he said. Myria has sent multiple clients to the Met Gala over the years and has brokered introductions between some of the world’s richest people and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, so that the clients could become benefactors and build relationships in Hollywood. “No matter what financial resources I have, I could not have figured that out,” said the billionaire client, who attended the Oscars and Vanity Fair afterparty after Flemings made an introduction.

David Dezso, a former member of special forces who now runs a risk management firm that sometimes partners with Flemings, said trust is a requisite of the relationship. The work predominantly involves what he described as “travel risk protection” for billionaires in areas like Brazil, Mexico, and Europe. The timelines can sometimes feel “almost impossible” and when Flemings calls, Dezso doesn’t have time to work out a legally binding scope of work. But Flemings has never failed him.

At the highest levels, sellers often have considerations beyond money, a primary reason they often aren’t available to the highest bidder. The reason for the secrecy is that the seller wants to curate their buyers. “If you want access to things that other people don’t have access to, part of the equation is always who is asking,” said Flemings. The issue then becomes figuring out how to beat out the rest of the people with seemingly limitless resources to gain special and privileged access. More often than one might expect, the final decision doesn’t come down to money, but one’s personal branding. It’s perhaps not necessary to be decent, but it helps to be cool. At a minimum, the person who can get you into the season premiere of Saturday Night Live wants to feel assured they won’t end up embarrassed for having done so.

Because of this “cold, hard reality,” Flemings’ carefully vets both clients and providers, including a live interview. Clients and vendors who make the cut then are rated on a scale of zero to 10. “People who are kind and easy to work with get increased access, and people who are shitty get diminished access,” he said. Flemings is adamant that Myria members are generally decent, but some bad apples slip through the cracks, and Flemings estimates he has had to ban an average of one client a year for misbehaving. “There are some people who don’t respect other people … I had one guy get out of line with my female staff,” he said. “It’s not worth the money.”

Of course, money helps. Flemings has cultivated relationships with the boards of organizations and occasionally expresses “the willingness of our client to be supportive of their endeavors,” such as hosting dinners or otherwise becoming more involved, however that may be possible. The implication is clear.

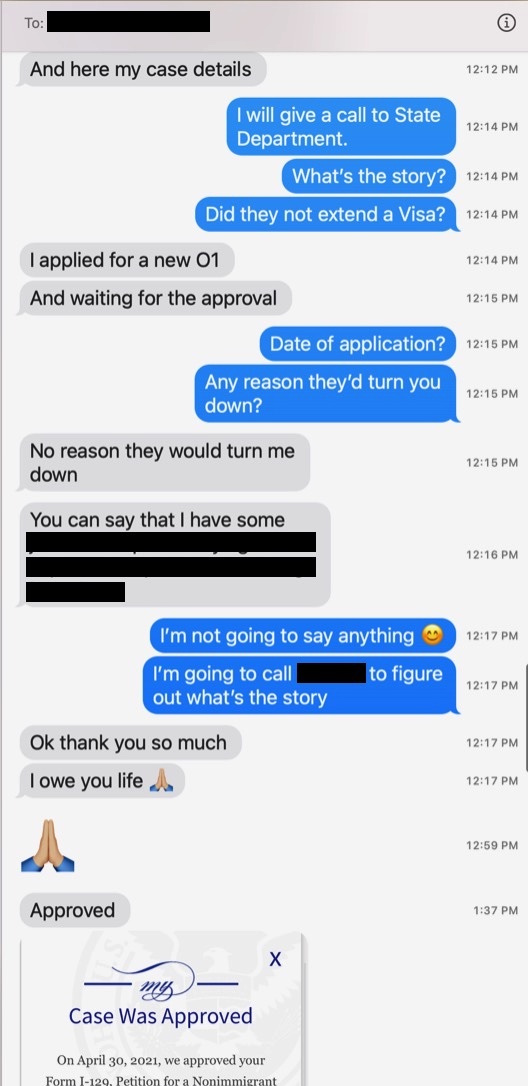

It all works, sometimes in miraculous ways. When a client was having trouble with a visa extension after government buildings shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic, he was able to identify the gatekeeper amid the government bureaucracy and have his client’s case resolved in just over an hour after the initial request. Foreseeing my skepticism, he showed me the texts as proof of the power of knowing who to contact, and already having enough of a relationship to call in a favor.

“I didn’t pay anyone,” he said with a smile. “Literally just called a friend.”

Flemings’ claim that he is “two degrees of separation” from any significant gatekeeper in the world felt dubious to me. But he insisted it wasn’t as far-fetched as it seemed. The key, he continued, was cultivating relationships with what he called “super connectors,” “Eigenvectors,” or “the central nodes in any network,” in the places the rich most often want to visit and the industries with which they want to interact. If they don’t know how to make it work directly, they’ll usually know who the next call should be—a celebrity can connect to a politician, who knows a government official, etc.

In total, Flemings said there were only about 20 markets around the world that the richest people in the world care to visit—places like New York, Dubai, Ibiza, Paris, Tokyo, and the south of France—and roughly 15 categories of activities—oftentimes, they are in touring, government, and luxury services—that interest them, outside of a few edge cases. If you have enough connectors to cover each of those categories in each of those places, you can mostly cover “the zeitgeist” of the rich, he said. “It’s much more finite than you realize.”

Two years ago, Flemings started Myria as a more professionalized, natural evolution of The Blue. The Blue’s growing client list, and the flights and movement that it required, had exhausted Flemings. He considered adopting what he called a “law firm business model,” with a local managing partner in every major hub. But that didn’t sit right with him.

So he started to put together something tailor-made for his tech-heavy clientele: an app, where Myria clients can make specific requests using the prompt “I want to _.” A member of the concierge team then sends out the request to the company’s network of providers on an “Uber-style” marketplace, as Flemings put it. If they get multiple offers, Myria makes a determination, so the client isn’t forced to waste time choosing. For its services, Myria decided to charge clients $25,000—The Blue had charged $50,000—as well as an additional fee per request, which varies according to degree of difficulty. The Silicon Valley spin on Fleming’s idea quickly garnered interest, and, in 2022, Myria earned investment from the influential accelerator Y Combinator and others.

Like any half-decent startup founder, Flemings has figured out a way to spin his new startup as not just a useful service for the rich to have fun, but a way to make the world a better place. At one point, Flemings expressed a soft and carefully managed criticism of capitalism to me, the kind a billionaire might find just OK enough, saying that the degree of wealth concentration amongst the highest echelons of society was not healthy for anyone—an opinion he shares with none other than JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon.

“We have to remember: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates—for all of their wealth, they did not invent capitalism. They were born into it. And capitalism was invented, let’s just say it, by our ancestors who didn’t know very much,” he said. “When capitalism was invented, the brightest scientific human minds believed, not just that the Earth was flat, but that the Earth was the center of the universe. They believe the sun revolved around the Earth, that brown-skinned people were inferior, that female sexual desire was a mental illness.

“Well, we’ve gotten rid of all of those other ideas, but we’ve kept capitalism and we’ve enshrined it as some sort of almost holy idea.”

Flemings positions his venture as a way to ever so slightly improve an archaic system, by making more of the money trickle down. Myria, he said, is a competitor to the Forbes billionaire list, convincing the rich to spend money as possible instead of stack it. “We believe that the world’s richest people should be having more fun and spending more money. We believe that that is actually for the greater good,” he told me.

Flemings’ degree of empathy for the world’s billionaires, which even Tom Wambsgans would be hard-pressed to match, makes more than a little business sense: Flemings is in the business of taking their concerns seriously. They are his customers. As a result, he unsurprisingly comes to their defense.

“They’re $1 billion out of an $80 trillion global economy. Even if they just took a billion dollars, converted it to cash and set it on a street corner in Manhattan, it doesn’t change the system. So, they, even in that position, are, like, ‘How do we fix something so big, so out of my control, and so overwhelming?’” he told me. “My observation is that it’s systemic, and that no one has their hand on the wheel. The systems are too big and too crazy, and no one really knows what they’re doing.” But there comes a point where Flemings’ billionaire empathy can extend so far out that it almost strips away the agency of a group with, at an absolute minimum, a disproprionate ability to affect societal change.

“We’re not going to shame the world’s rich into helping to create a better society,” he told me the second time we spoke on record. “We need to open our arms. People are people and trying to figure this thing out together.” It was a perfect Rey Flemings line: empathetic, even-keeled, and exactly what the richest people in the world would want to hear.

More

From VICE

-

Mountaineers on Everest. PHUNJO LAMA/AFP via Getty Images -

VICE host Matt Shea with Andrew Tate, before their relationship went south. Credit: VICE/BBC -

Jeremy Strong and Sebastian Stan, playing Ray Cohn and Donald Trump in new movie 'The Apprentice' -

Photo by Dave Lewis/Shutterstock