Unarmed combat was the trade of the street urchin or penniless thug more than the professional soldier. Fist fighting was peasant business and yet many of the earlier written records of actual systems of unarmed combat are found in military manuals, though they are often an afterthought tacked on after pages devoted to the discussion of armed tactics.

Whether it was the Jixiao Xinshu (‘New Treatise on Military Efficiency) written by the Chinese general Qi Jiguang in the 1550s, or Fior di Battaglia (‘The Flower of Battle’) by the Italian, Fiore de’i Liberi in 1404, armed martial arts methods were closely linked to unarmed ones and considered just two parts of a whole. Examining how swordsmanship and unarmed fighting influenced each other, particularly after they had become separate disciplines, makes for an interesting study.

Videos by VICE

Strength versus Length

Ernest Hemingway recalled in the memoir of his time in Paris, released posthumously as A Moveable Feast, his attempts to teach Ezra Pound to box:

Ezra had not been boxing very long and I was embarrassed at having him work in front of anyone he knew, and I tried to make him look as good as possible. But it was not very good because he knew how to fence and I was still working to make his left into his boxing hand and move his left foot forward always and bring his right foot up parallel with it. It was just basic moves. I was never able to teach him to throw a left hook and to teach him to shorten his right was something for the future.

Leading with the right foot is a mark of modern fencing with lighter swords. In Early Modern texts on swordsmanship, whether the sword is held in one hand or two, the left leg is the leading leg. With the rise of dueling, the rapier and the sabre became more popular, the popularity of the longsword declined, and the fencing meta came to reflect this. Much of this, too, came from the decreased importance of hand-to-hand combat in warfare and firearms making armor largely irrelevant. No armor, no need for heavy longswords.

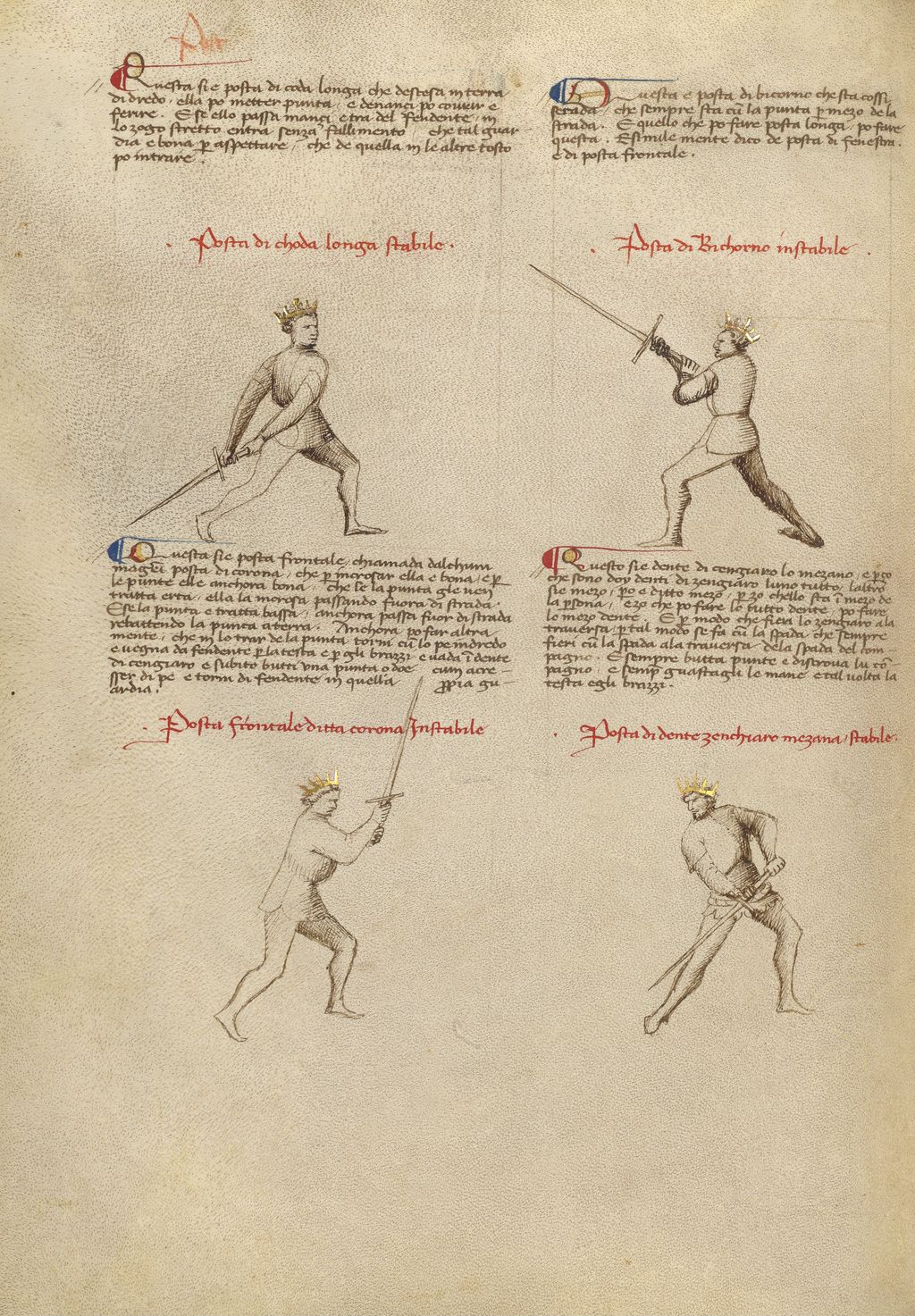

The left leg leading in The Flower of Battle, 1404.

The right foot leading in Demenico Angelo’s L’Ecole des Armes, 1763.

The great boxing coach, Edwin Haislet believed that a high number of southpaws and the focus on the long straight lead in England…

[…]seems to have developed from the fencing position, with the right foot and hand carried forward, with the left side of the body back. As the desire developed to hit with both hands, the square and then gradually the present so-called orthodox stance evolved.

It is an interesting theory, and Haislet cites another earlier writer on boxing, Norman Clarke as his source. Though southpaws have always been considered an oddity and there never seemed to be an epidemic of them in England. The focus on and pride of the British as a nation in the jab (or ‘the jolt’), to the point of champions like ‘Peerless’ Jim Driscoll and Jimmy Wilde writing several whole treatises on why the refused to learn to infight, suggests some strength in the link.

Looking at two handed swordsmanship across the world, from Germanic texts to the Japanese style of swordsmanship, the left foot is almost always carried forward. Why? Because when you are swinging a heavy blade for power, you naturally stand with your strong arm and leg to the rear. It doesn’t matter whether you’re swinging a battle-axe or an axe to chop wood, the average person will put their weak foot forward and throw their weight onto it. And this, Haislet and others assert, is the reason that in the earliest days of bareknuckle pugilism, we came to lead with the left foot. When swinging your right hand as hard as you possibly can, you need you need the right foot behind you and some distance to throw it through.

The parallel is an interesting one, and could have happened without fencing and boxing ever meeting. When hitting for power—as with the longsword or in the early days of bareknuckle fighting—the weak foot was placed in front. When working for range and speed—as with the rapier or sabre—the strong foot and hand are placed in front. Perhaps most fascinating is that a high number of right handers are now placing their strong hand in front in boxing, kickboxing and MMA for the dexterity it offers as the lead.

The sword hand was so significant that many believe the clockwise rise of spiral staircases in a great number of European castles was to give the man descending the stairs room to swing his right hand, while the invading man’s swing would be disrupted by the central column. Some English families even insisted on teaching their sons to fight left handed for such an eventuality.

The entire concept of handedness is a fascinating one as the influences of any sport can run into another. Many wrestlers learn to lead with their right foot, and then choose to learn to strike that way once they enter MMA. Most people when grappling for the first time with no combat sports experience will prefer to lead with their right foot when standing in guard, attempting a pass, or kneeling in combat base while many who come from a striking background will naturally lead with their left and change when they find the former is more comfortable.

It is no secret that Bruce Lee was fascinated with the footwork of fencing. The tournament kicking meta of the day had martial artists standing almost entirely side on and skipping up to land side kicks. Lee became fascinated with the similarities, aided by the fact that his own brother, Peter was a champion fencer. It all revolved around that bursting in to land first and land hard. Lee’s pendulum step and burning step methods to set up his kicks supposedly came from his studies in fencing. The popularity of point fighting at the time of Lee’s rise to prominence in turn stemmed from a relationship between swordsmanship and unarmed martial arts on the other side of the globe.

Gichin Funakoshi is considered to be man mostly responsible for popularizing karate on the Japanese mainland, largely due to his relationship with the founder of Judo, Jigoro Kano, and his ability to form clubs in Tokyo’s universities. These university clubs were keen to compete, though Funakoshi loathed the idea of turning the indigenous Okinawan fighting art into a sport. Some, like Funakoshi’s peer, Kenwa Mabuni, thought that competing with true karate methods was far too dangerous (real karate being all about grabbing the hair and testes, after all). This, combined with Funakoshi’s warning to consider the arms and legs as live blades, led to the point sparring of modern karate where everything begins and ends with the first strike.

Gunnar Nelson, a skilled karateka, closes the distance, strikes, and moves into the clinch in an instant.

If you are pretending that both you and the opponent can kill with one touch (or you’re daft enough to believe it), leaping in and out becomes the most important point. In fact that is what kendo, the Japanese method of fencing, is all about. Many of the university karate students had studied kendo and subsequently tobi-komi or ‘leaping in’ techniques became the competition meta.

Making ground is the single most important facet of point fighting.

Lee’s own belief that the intercepting strike was the true core of martial arts also merges with fencing beliefs. The perfect time to catch an opponent is as he commits to his own blow.

In the sport of fencing it is simply the surprise factor that is important but in a game of real blows the opponent’s weight is of primary importance. Whether it is raising the pike against a charging horse or meeting the bull as he is guided past using the weight of the opponent to add force to the collision is of primary importance. And running him a few inches onto it before he realizes is another benefit.

Luis Freg killing a bull in an example from Death in the Afternoon. The weight of the bull in its charge does the killing.

Lyoto Machida steps to the side of Rashad Evans as Evans provides the force for the blow.

Machida in a less graceful head on collision with Ryan Bader.

In Japanese swordsmanship there are the Three Initiatives which we examined in the last episode of Jack Slack’s Ringcraft, and they will make another appearance in our imminent next episode. These initiatives are Sen, Go-no-sen, and Sen-no-sen. To hit first, to evade or parry and return, and to strike as the opponent strikes but land first respectively. In modern fencing there are the simple and compound attack, the parry-riposte and other counter-attacks, and the stop hit.

Bruce Lee’s belief in Wing Chun trapping (along with Dan Inosanto’s use of Filipino trapping arts) also meshed well with the fencing ideas of prise de fer, wherein the opponent’s blade is controlled with one’s own and moved out of position to different angles. This is identical to handfighting or trapping in unarmed combat and particularly relevant in southpaw versus orthodox bouts wherein the lead hands are almost on top of each other anyway. Almost any method of controlling the blade into an attack can be performed with bare handed pulls, slaps, and jabs from this scenario.

Lee was also a fan of the appel—the stamping of the front foot to distract or draw a reaction from the opponent. They say that when the old time boxer, Joe Gans threw his jab, he stamped heavy on the floor. When he didn’t jab and just stamped, he could draw a panicked response from his man.

It will be interesting to see, now that fencing is not as popular as in the days of dueling whether it will continue to influence unarmed martial arts, or if a more popular armed pastime will take its place. Certainly, eskrima and other Filipino systems have found remarkable popularity in recent years and the idea of ‘defanging the snake’ and other base principles from that art can be readily applied in a bare-handed setting with a little practice. Whatever the case, ideas can be stolen and converted from almost any tradition—you never know what will catch on next.