Astronomers are perplexed by the unexplained disappearance of a massive star located 75 million light years away.

A decade ago, light from this colossal star brightened its entire host galaxy, which is officially known as PHL 293B and is nicknamed the Kinman Dwarf. But when scientists checked back in on this farflung system last summer, the glow of the star—estimated to be roughly 100 times more massive than the Sun—had been extinguished. The head-scratching discovery was announced in a study published on Tuesday in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Videos by VICE

“We were quite surprised when we couldn’t find the star,” said lead author Andrew Allan, a PhD student at Trinity College Dublin, in a call. “It is a very extreme star, and it has quite a strong wind, so we can distinguish it from the galaxy. That’s what we couldn’t see in the newer observations.”

The mysterious series of events began when Allan and his colleagues imaged the Kinman Dwarf in August 2019, using the ESPRESSO instrument at the Very Large Telescope in Chile. The team initially set out to learn more about massive stars located in galaxies with low metal densities. Given that the starlit Kinman Dwarf had been observed by other astronomers between 2001 and 2011, the team knew that it would be a good target for their research.

“Not a lot is understood about stars in those kinds of environments, so that was the main reason we wanted to look,” Allan said. “We are interested in massive stars at the end of their lives in those kinds of environments, so we were really just hoping to get a better resolution observation.”

What they ultimately got was the absence of an observation. The weird disappearance of the massive star was so tantalizing that the European Southern Observatory, which manages the VLT, gave the team another shot to image the system with an instrument called X-Shooter.

Those images, captured in December, confirmed that the original observation was not a fluke and that the star had faded for some unknown reason. Even weirder, there was no sign of a supernova—the explosive and radiant death of a massive star—which would have accounted for its sudden departure.

Allan and his colleagues considered several explanations for the observations, and eventually narrowed down the possibilities to two scenarios: Survival or death.

If the star lived, we could be witnessing the fallout of its huge senescent outbursts, which may have enshrouded it in dust clouds that dimmed its light. If the star died, it may have collapsed into a black hole without ever producing a supernova.

This second option seems bizarre, but it would not be the first potential “failed supernova” that has been detected by scientists. Another star appears to have fizzled out without any fireworks in a galaxy 22 million light years away, though it was only 25 times as massive as the Sun (which is still pretty huge).

“That was the only other observation of it happening,” Allan said, though he noted that “some of the models and current theories do predict” that some massive stars might die in the dark.

“It just hasn’t really been observed, because obviously it is much harder to observe it,” he explained. “It’s easier to observe a supernova.”

In other words, massive stars may collapse without producing supernovae more commonly than we think, but we do not capture their shadowy demises with light-receiving telescopes. Indeed, it’s unusual to even capture living luminous stars like the one that is—or perhaps, isn’t?—in the Kinman Dwarf. These huge stars shine bright, but they also tend to flame out just a few million years after they are born.

“Massive stars are rare in general,” Allan said. “The more massive they are, the less likely you’ll be to find them. They live a lot faster, and they die a lot quicker, than lower-mass stars.”

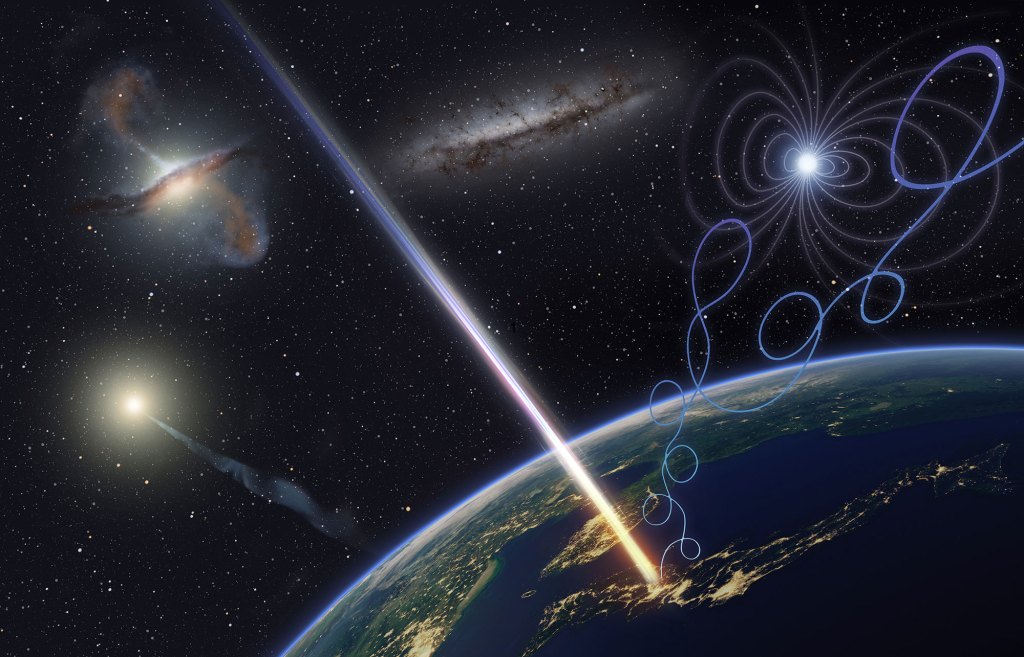

Massive stars are also cosmic forges that create many of the elements that make up new generations of stars, planets, and even lifeforms like humans. A better understanding of their life cycles could help resolve a host of unsolved mysteries about our universe, such as “the link between supernovae and gamma-ray bursts” and “the early evolution of the Universe,” according to the new study.

To that point, Allan and his colleagues plan to examine the Kinman Dwarf with the Hubble Space Telescope, which may shed light on the fate of this monster star. The team found a never-before-published Hubble image of the system, captured in 2011, that could provide the perfect contrast to a new picture by the space telescope.

“Just by comparing a before and after picture of the galaxy, we’d hopefully be able to pick out, first of all, the star itself, and then maybe what happened to the star and why it disappeared,” Allan said.