If you’re using the word “plantation” to describe or market your food, consider this a formal request to stop.

I’d never noticed its usage until a friend pointed out the “plantation slaw” on a restaurant’s menu in Jamestown, North Carolina. Then, I started seeing it everywhere: plantation quail at a restaurant in Hudson, NY, plantation mint tea at a friend’s house in Massachusetts, plantation rum hailing from the Caribbean.

Videos by VICE

In the most generous light, the word can be seen as a clumsy stand-in for “Southern.” But the fraught, loaded term draws much more to mind. If you’re slapping “plantation” on your menu, you’re probably doing so out of a sense of wanting to evoke something bigger: a sense of heritage, history, and place. That’s part of the reason why in the U.S., regardless of intent, it’s impossible to separate the word “plantation” from hundreds of years of slavery on plantations throughout the American South and beyond.

But as James Beard-winning food writer Osayi Endolyn told MUNCHIES, the word doesn’t actually tell you anything about how the food tastes.

“It adds a layer of discomfort to me that could’ve been wholly avoided if you used different terminology,” Endolyn said. “It distracts from how the food actually is.”

That lack of clarity is an easy reason to discontinue using the word. Another is the history of how it’s been used.

These “plantation” foods and products aren’t new. I quickly found a “plantation pecan pie” recipe in a 1974 Danville, Va. newspaper and an “award-winning plantation turkey” recipe in a 1982 newspaper from Raeford, NC. At least two Louisiana cookbooks from the same time period use “plantation” in their titles. There used to be a popular Old Plantation Barbecue restaurant in Birmingham, Ala. and Pittypat’s Porch in Atlanta advertised a mint julep that would make you “feel like a plantation owner.” (The restaurant has since changed the menu to say, “feel like a Kentucky Derby winner.”)

John T. Edge, the director of the Southern Foodways Alliance and author of The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South, told me that there’s a long history of restaurants referencing or alluding to plantations. After Gone with the Wind—a highly lauded 1939 film that idealized and whitewashed life on a Southern plantation around the Civil War—white-owned restaurants capitalized on this imagined history, Edge said. Most are gone now, he said, but a few remain.

“There’s a range of restaurants across the region that have used the word ‘plantation,’” Edge said, “to sell a certain Southern mythology grounded in white supremacy and racism. There’s no way to disentangle those restaurants and the selling of those ideas… from enslavement and the selling of white supremacy.”

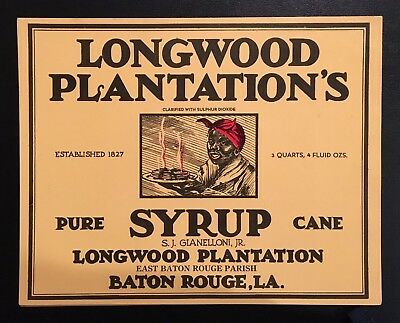

Michael Twitty, author of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African-American Culinary History in the Old South, tied it to a legacy of white-owned businesses using Black faces to sell their products.

“Once upon a time, they were much more blatant,” Twitty told MUNCHIES. “Food was sold—sugar, spices, other ingredients—with the image of the ‘happy darkie,’ happily laboring away at the plantation so that you could have the end product.”

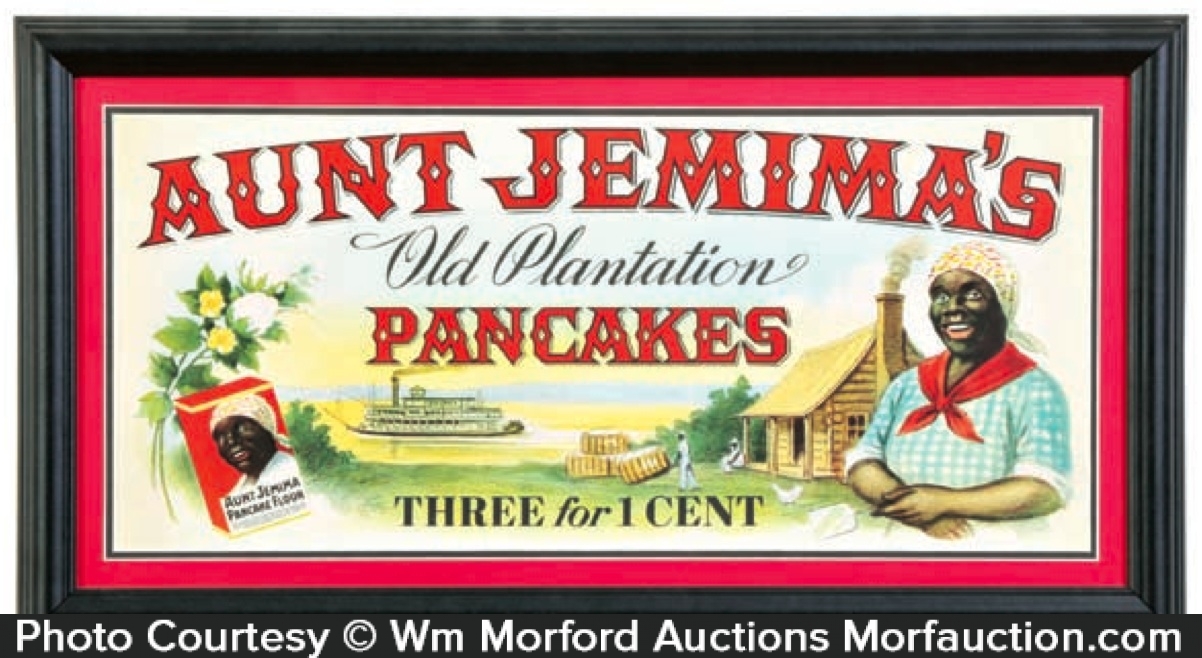

A vintage ad for Aunt Jemima pancake flour illustrates the link between the term and the broader context. “No other pancakes can have Aunt Jemima’s old-time plantation flavor,” it reads. As Cornell University professor Riché Richardson wrote in a New York Times op-ed, the deeply problematic Aunt Jemima caricature is “an outgrowth of Old South plantation nostalgia and romance grounded in an idea about the ‘mammy,’ a devoted and submissive servant who eagerly nurtured the children of her white master and mistress while neglecting her own.” (Plenty else has been written about why the character is so fucked up.)

Aunt Jemima products are just one example of how racist iconography in the food world wasn’t contained to the South. Consider the Coon Chicken Inn, a fried chicken restaurant in Seattle that included a towering minstrel-style blackface (and was, of course, white-owned).

There are modern corollaries too, like Beauregard Dixie Vodka from South Carolina, which lionizes a Confederate general and emerges from the same swamp of historical make-believe as the term “plantation.” Whether a restaurant or business owner using these terms purposefully elicits this history or not, the effect is the same. For many consumers, the term “plantation” will immediately conjure slavery.

“To evoke a plantation is to evoke an era when men and women were shackled and sold and beaten,” Edge said, “To reclaim that term and project it as if it wasn’t the equivalent of ‘white supremacy slaw,’ ‘white supremacy biscuits’… think about how that would play on a menu.”

Adrian Miller, author of Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time, assumes people using the term “plantation” are trying to portray an image of Southern hospitality, with people relaxing on a veranda and sipping mint juleps with a nice breeze.

“I’d like to give people the benefit of the doubt,” Miller said. “People are maybe thinking ‘plantation’ means ‘Southern’ without any real feeling for the cultural connotations of what that word means.”

But it doesn’t mean “Southern” to him.

“To me, it’s the culinary form of ‘Make America Great Again,’” he said, “this kind of search for a more ‘innocent’ America, when we didn’t have all these kinds of diverse people making a claim on society.”

He likened it to a political dog whistle, adding: “It’s just one more step of refinement from having actual African-Americans on products to display that [plantation] life.”

Nicole A. Taylor, a chef and the author of The Up South Cookbook: Chasing Dixie in a Brooklyn Kitchen, also thinks of the president’s catchphrase when she hears the word “plantation.”

“It’s almost like ‘Make America Great Again,’ that has so many meanings,” she told me. “What the hell are they trying to say? I just think there are so many other ways to be able to describe food other than to use the word ‘plantation.’ There are certain places down South I don’t go because I don’t want to see the word ‘plantation’ on something, because then I’m like, am I even supposed to be in here?”

Taylor said she’d never use the term to describe one of her recipes and doesn’t know of any Black-owned establishments that do, either.

“They’re not speaking to a Black person when they’re saying ‘plantation,” she said. “Or they’re trying to say, ‘There’s a Black person cooking in the back.’ What more do I need to ask them? They’re telling me exactly what I need to know.”

That fits with a tradition of white women taking recipes from their enslaved cooks and publishing them as their own, Miller explained.

“It was a weird dynamic that, even though the white woman wasn’t doing the cooking, she got the reputation as the exceptional hostess,” he said. That desire for delicious food cooked by Black hands—especially from a “safe” and docile caricature like Aunt Jemima—could be part of the term’s appeal for some white people, Taylor added.

Twitty agreed that a business using the term is targeting a white clientele. In his widely lauded book, he writes about visiting the North Carolina plantation house owned by one of his white ancestors.

“The big house is still standing,” he told me. “For somebody who was white looking at this, they might think about joining ‘the good life.’ But as somebody who is a Black descendant of said white man, I could only look at that and go, ‘I would’ve never even have been allowed to eat at this man’s table.’ The idea that I would be partaking in the pleasure and the leisure, that would’ve been inconceivable.”

That’s the rub—if the term “plantation” appeals to you, chances are you’re more likely to see yourself in the white slave owner.

The term’s use isn’t limited to food, of course. It’s all over housing complexes, especially in the South, as well as resorts and other developments.

“It’s kind of creepy,” Twitty said. “If you imagine… a concentration camp or an internment camp that would then lend its name to a mall, even the thought of it makes you sick. But there are hundreds, hundreds of places named after former plantations.”

That the problem is widespread doesn’t relieve any of the food world’s responsibility. Until we—as a country, but especially white people like me—deal with our history openly and honestly, these issues will persist. Even if accidental, “plantation” dishes and products add to a legacy of fictionalized history that seeks to erase hundreds of years of human trafficking, torture, rape, and forced labor without erasing any of the pain or generational inequities that resulted. Attempts to cherry-pick words like “plantation” out of our incredibly painful history only underscores white America’s refusal to openly and honestly grapple with race.

“I don’t know why we have to have the right to use the term ‘plantation’ casually, but if that’s where people feel like they need to be, then do the work to get there, and we’ll see,” Endolyn said. “All of this stuff is symptomatic of a lot of pain that we all have. There’s a lot of pretense in plantation slaw, whether the restaurateur realizes it or not.”

In an era when white supremacists openly march in the streets, it’s more than a little irresponsible to evoke the antebellum South in a restaurant setting. And it’s completely unnecessary. As Endolyn said, “I just don’t understand why you’d want people to think about that when they’re biting into a big sandwich.”

The simplest, cleanest solution is to stop using the term. In the case of restaurants, it’s laughable how little effort it would require to pull it from menus. As Taylor said: “Plantation is not an adjective, it’s a place.” Put an adjective in there instead, if need be.

Alternately, restaurants could provide more context on their menus. If, for example, the chicken comes from a place still operating under the term “plantation,” restaurants could add a note explaining that, Miller offered. The same goes for a recipe handed down from a plantation; honor the people who actually developed and prepared it by adding information.

The switch would admittedly be more challenging for products. And, as Endolyn wrote in a award-winning piece about plantation rum, the context may be different outside the United States. But it’s still incumbent upon us to interrogate the meanings of loaded terms like this, to be more thoughtful about how we deploy them, and to push businesses to do better.

When my friend first pointed out the “plantation slaw” on that North Carolina menu, I reached out to the restaurant privately to express my objection. The restaurant’s white owner did not respond well. Some others likely won’t either. I found restaurants across the country using the term on their menus. A Michigan brewery, a California tapas restaurant, a Colorado ski resort, and an Alabama country club all currently offer “plantation slaw.” Search results for other “plantation” foods are similar; they’re predominantly white spaces, there’s never any context added, and it’s usually alongside some kind of Southern food. I didn’t call them all to ask for explanations. That’s because I’m not all that concerned with their intent—chances are, not a lot of thought went into it. What I care about is their impact, and the legacy of white supremacy they’re tapping into. That’s what they should care about, too.

More

From VICE

-

View of the submerged stone bridge from Genovesa Cave, Mallorca, Spain. Photo by R. Landreth -

-

-