In case you hadn’t heard, there’s a ‘Pterosaur Renaissance’ on, which means it’s a good time to be a fan of ancient flying reptiles. Most recently, paleontologists based out of Brazil announced the discovery of a new pterosaur species named Caiuajara dobruskii.

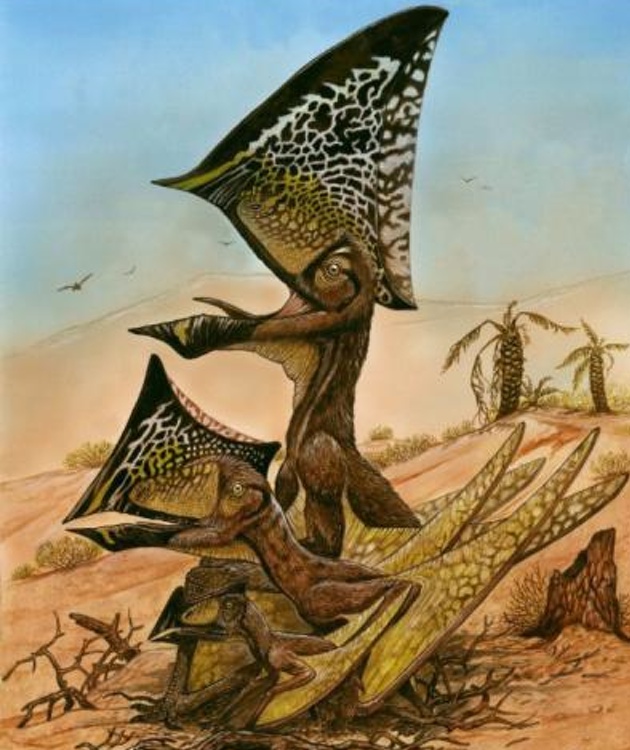

About 50 individuals of the new species were found, from all age groups. Based on the comparative morphology of the juveniles and adults, the Brazilian team suggests that this particular species was very social, and taught its ptero-toddlers how to fly at a very young age. The head crest of the Caiuajara dobruskii was also found to be distinct from other members of its clade, with an almost sail-like formation lodged right between the animal’s eyes.

Videos by VICE

As unique as the discovery of Caiuajara is, it is only the latest chapter in what some scientists have dubbed the “Pterosaur renaissance.” Since the late 1980s, discoveries of new pterosaur species began to accelerate, and fresh findings have been spiking over the last few years.

A reconstruction of three growth stages of the new pterosaur Caiuajara dobruskii. Image: Maurilio Oliveira/Museu Nacional-UFRJ.

The phenomenon could be more broadly be described as a general paleontological renaissance, as techniques for seeking out and swiftly excavating fossils have improved dramatically in the last 20-odd years. As paleontologist Steve Brusatte pointed out to Motherboard a few weeks back, “people are finding a new dinosaur species somewhere around the world once a week now.”

Pterosaurs had much lighter and more fragile bones than their land-bound dinosaur pals, so comparatively, they are still a rarer find. But two new pterosaur bonebeds in Brazil and China have been discovered in the last two decades which have launched the study of these Mesozoic fliers to new heights.

“These new places have opened a whole new chapter in pterosaur research because of the immense diversity and numbers of pterosaurs that have been coming out,” said Mark Norell, who curated the American Museum of Natural History’s exhibit Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of the Dinosaurs. “It’s just exploded in both the diversity and the number of specimens.”

Dinosaur paleoart is cool enough on its own merits, but the subset focusing on the dinosaurs’ airborne cousins is even wilder. It’s only a matter of time until we have a book of pterosaur drawings done up in the style of Audubon’s Birds of America, to demonstrate the beauty and diversity of these long-dead aviators.

But until that time, here’s the next best thing: a bunch of talented artists riffing on the most bizarre and majestic species of pterosaur yet to be discovered and placed in the fossil record. Consider it your front-row seat to the pterosaur Renaissance.

Pterodactyllus antiquus. Image: Nobu Tamura.

Pterosaurs are popularly referred to as pterodactyls, but Pterodactyllus antiquus was just the first species of the group to be found.

Pterodaustro interpretation. Image: Elperdido1965.

The Pterodaustro genus of pterosaurs were probably krill-feeders, judging by their thousands of bizarre, bristled teeth.

Nyctosaurus gracilis. Image: Nobu Tamura.

The striking cranial features of the Nyctosaurus gracilis have puzzled scientists for over a century. The interpretation above depicts the structure as a straight-up antler, but it’s possible the animal may have used it as scaffolding for a large, sail-like crest, as pictured below. Pterosaurs were all about wacky cranial decorations, after all.

Nytosaurus with crest. Image: PaleoFreak.

Nyctosaurus: The wizard of the Cretaceous skies.

Quetzalcoatlus northropi. Image: Mark Witton and Darren Naish.

Quetzalcoatlus northropi was the largest animal ever to fly. With a wingspan reaching almost 40 feet, this giant pterosaur was the size of a giraffe when grounded. Most pterosaurs had to content themselves with eating small fish, bugs, or carrion, but Quetzalcoatlus may have actually dined on small dinosaurs like the baby sauropod in the picture. Bad luck, Littlefoot.

Thalassodromeus interpretation. Image: PWNZ3R-Dragon.

Thalassodromeus was a close relative of Quetzalcoatlus northropi, but instead of eating adorable baby dinosaurs, it specialized in skimming the ocean surface for food.

Model of a Nemicolopterus crypticus. Image: Mallimaakari.

The Nemicolopterus crypticus is one of the smallest pterosaurs ever discovered, with a wingspan of only 10 inches.

Pteranodon in flight. Image: Vlad Konstantinov.

Pteranodon fossils are the most abundant of any pterosaur, with over a thousand specimens collected. There was a lot of diversity in size within the group, with the largest members reaching wingspans of about 20 feet.

Europejara olcadesorum. Image: Nobu Tamura.

Pterosaurs evolved all kinds of funky cranial crests, but few are more distinctive than that of the Europejara olcadesorum, a species discovered in 2012. The animal is both the oldest member of its genus, and the oldest pterosaur ever found without teeth. It had a wingspan of about six feet.

Eudimorphodon interpretation. Image: Fabio Pastori.

Eudimorphodon had a freaky smile, packed with dozens of sharp, outwardly protruding teeth. The fangs were probably used to catch and skewer fish, and to inspire nightmares in small children epochs later.

Jeholopterus interpretation. Image: Spikeheila.

This interpretation of the small pterosaur Jeholopterus ninchengensis is cartoonish, but it captures how unique its skull was compared to other pterosaurs. The animal’s rounded face and bat-like frame has puzzled paleontologists since the only specimen was found in 2002. Some suggest that the animal had a lure connected to its forehead like an angler fish, and others speculating that it was a vampire that could suck the blood of tough-hided dinosaurs. Until other specimens are found, questions about Jeholopterus’s odd features are likely to persist.

Samrukia nessovi. Image: Nobu Tamura.

In 2011, paleontologists discovered the jawbone of an 80-million-year-old giant biped named Samrukia nessovi. Ever since, a debate has been raging over what clade the animal belonged to—birds or pterosaurs. If it was the latter, Samrukia would be the first flightless pterosaur ever found. If birds like ostriches and penguins can trade in their flying abilities for other adaptations, why not pterosaurs?

It’s an interesting idea, and further goes to show that researchers have only just begun to scratch the surface of the pterosaurian world.

More

From VICE

-

Lectric Ebikes -

(Photo by NASA via Getty Images) -

(Photo by Edlund Aviation Photography / Getty Images) -

Collage by VICE