High Wire is Maia Szalavitz’s reported opinion column on drugs and drug policy.

When 23-year-old Michael* overdosed several years ago in his family’s Long Island home, it was sheer luck that his father found him in time to save his life. Because Michael’s grandmother was ill, his dad had gotten up unusually early for a Sunday morning visit. But when he came downstairs, he found a terrifying scene: His son’s girlfriend had collapsed in the living room and Michael was lying unresponsive in the kitchen. Both were blue.

Videos by VICE

“I thought we had lost them,” says Michael’s mom, Mary*. Fortunately, however, EMS workers arrived in time to save the young couple.

Mary decided that she needed to be prepared, should such an emergency ever happen again. She got trained to administer the opioid overdose antidote, naloxone (brand name Narcan)—and, recently, when she needed to renew her supply, she found a new and convenient source, which she heard about at a support group for parents.

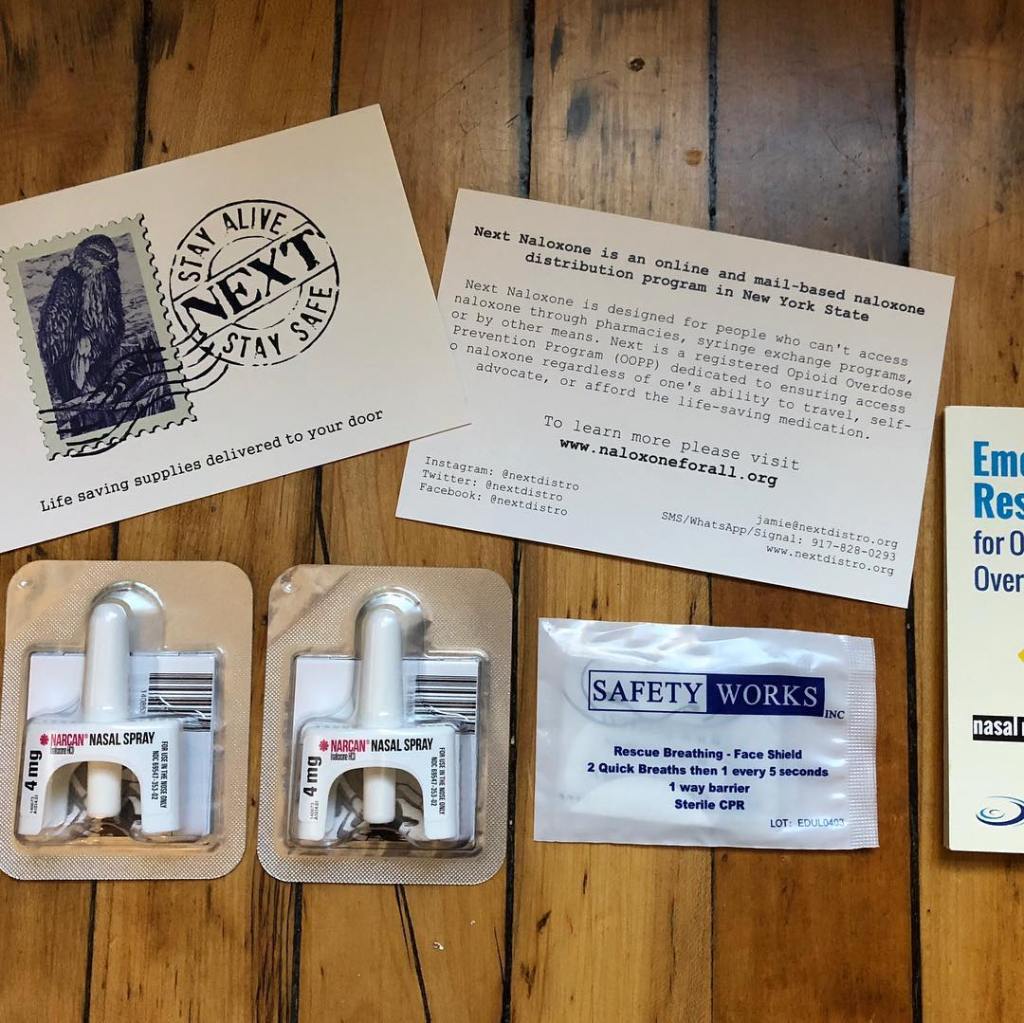

Mary ordered free naloxone online from a rapidly expanding program called NEXT Harm Reduction. Based in New York City and begun quietly in 2017, the organization has two separate projects: One provides naloxone and the other supplies clean needles to those who don’t have easy access to these life-saving tools. Since people can already order fentanyl and other harmful drugs via the darknet, NEXT wants to make obtaining items that reduce harm just as easy to get, says founder Jamie Favaro, a social worker and harm-reduction activist.

Indeed, the internet and the postal system may be the fastest and most efficient way to get safer injection supplies into the hands of all who need them. Despite significant progress in expanding access to naloxone and clean syringes, in many states, they’re still hard to come by.

Geography is one of the biggest obstacles for programs that aim to reduce drug-related harm. For one, even treatment centers for people with addiction who are completely abstinent—such as rehabs—encounter strong NIMBY (“Not in My Backyard”) responses when they try to open a new facility.

Finding locations to provide services for people who are still using is exponentially more difficult. As a result, even in blue states like New York, these programs are far less plentiful than they should be, especially in rural and suburban areas. And, particularly in small communities where everyone knows everyone, many people are embarrassed or afraid that they’ll be targeted by law enforcement if they’re seen visiting a program like a needle exchange.

Though many pharmacies are now supposed to sell naloxone without a prescription in states that have made provisions to allow it, pharmacist resistance, embarrassment, and high insurance co-pays often deter people from getting it at their local drugstore. Sending free supplies by mail eliminates these barriers.

Mail-order naloxone does face some regulatory challenges: Although many states make it available over-the-counter and the FDA is moving to change its status nationally, it’s still technically a prescription drug and, therefore, mailing it can be illegal in some places.

The drug comes in two types, a nasal spray and a less-expensive injectable, and the latter can also run into legal barriers related to mailing syringes in some states. NEXT is finding ways to work around this: For one, because the group is authorized by New York State as an Opioid Overdose Prevention Program (OOPP), sending naloxone and syringes is legal within the state.

Watch More from VICE:

The mail-order/internet harm reduction idea isn’t a new one: It was first introduced by Tracey Helton, author of The Big Fix, who is known as the “heroine of heroin.” Because she’d appeared in the 1999 HBO film Black Tar Heroin while homeless and desperately addicted—and because she has generously shared her own story of recovery—people started contacting the San Francisco-based writer for advice. Some asked her directly if she could send them naloxone.

Many of these folks had had an extremely different experience of opioid use than Helton had. “It was a whole new generation who was using,” she tells me. “They weren’t going to needle exchanges; some were buying their drugs off the internet.” And they were extremely isolated, socially and physically. Unlike prior generations, many of the people who contacted her weren’t part of a local drug-using crowd or group of friends; instead, they were taking drugs alone, secretly.

In 2013, Helton began sending naloxone and clean needles, free of charge, to people who emailed her, relying on her own income from a full-time job and on small donations from those who supported the work. She spread the word via social media, like the subreddit on opiates, and has since sent out thousands of packages. Since she started, she says she’s heard back from more than 400 people who used the naloxone she sent to save a life.

Inspired by Helton, Favaro decided she wanted to take the idea further and create a nonprofit program to extend this work around the country. (Helton is now on NEXT’s board of directors.) The New York state health department supplies NEXT with free naloxone, which NEXT sends to any state resident who requests it and watches a training video. (Because New York City is already well-supplied with naloxone services, however, she does not send it within the five boroughs.) Favaro’s group covers packaging and shipping costs, with support from small donors and the Comer Family Foundation.

But Favaro’s program also gets—and will respond to—naloxone requests from across the country, using medication from other sources. “We’re now up to 46 states,” she says, noting the locations to which the group has mailed packages.

Tennessee seems to be a real hotspot: When the NEXT naloxone website went live in late 2018, in the first month alone, it received dozens of requests from people in the Eastern region of that state. Favaro is working with a local harm-reduction group there—and, ultimately, she hopes to have an affiliate in each state, which would facilitate distribution, ensure legality within the receiving state, and ideally add sources of local funding. So far, she has affiliates in at least 12 states including Florida and California—but she won’t turn someone away if a state affiliate hasn’t yet been established.

Favaro says she’s received a few odd requests, including one from a man who was so nervous about how the package might be perceived that he asked her to draw hearts all over it so that it would look like it came from a long-distance girlfriend. The packaging is normally plain and discreet, but she says she was happy to draw the hearts to reassure him.

Right now, the organization is in desperate need of more donations, with Favaro spending her own money to sustain it. “It has taken over my life from minute we started it. The need has been absolutely overwhelming,” she says. In one recent week, she received more than 100 orders for naloxone. (Those interested in helping out can contact NEXT here).

To Mary, the program has already proven its worth many times over. In December, when Michael overdosed again, she was ready. She’d heard strange breathing noises coming from Michael’s bedroom—he sounded like he was talking to himself.

Concerned, her husband broke down the door and, as Michael tried to tell his parents he was OK, he turned blue and collapsed. They sprayed the naloxone into his nose and Michael’s father began doing rescue breathing while Mary called 911. A terrifying seven or eight minutes later, Michael woke up and asked his father what he was doing. He’s currently in addiction treatment and taking medication to prevent relapse.

“Thank god we had it here,” Mary says of the naloxone, “I don’t know what we would have done. I don’t think he would have made it until the ambulance got there. And, as soon as he went to hospital, I said to myself, ‘let me get on this website. I’ve got to get some more just in case.’”

*Names have been changed to protect privacy.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Tonic delivered to your inbox.