This story is part of OUTER LIMITS, a Motherboard series about people, technology, and going outside. Let us be your guide.

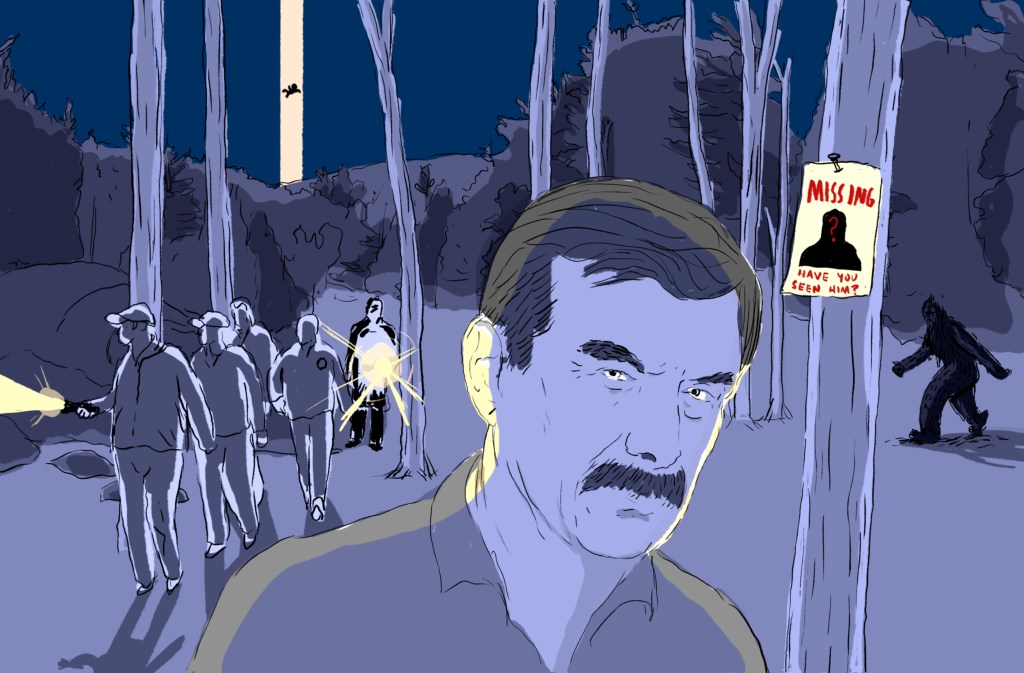

The disappearance of Stacy Ann Arras has a cultish online following. On dozens of Reddit threads and chat boards, thousands of people—strangers intimately familiar with her life—obsessively dissect her vanishing. The case is mysterious, eerie, and frustratingly unsolved.

Videos by VICE

Arras went missing from Yosemite National Park more than 30 years ago. She “just seems to have disappeared,” the park’s then-superintendent, Robert Binnewies, told the Fresno Bee.

It was in the afternoon on July 17, 1981, when a group of six, plus Arras and her father, rode into Sunrise High Sierra Camp on horseback. The camp sits 9,400 feet above sea level and is regarded for its historic significance, being the final stop in Yosemite’s “mountain chalet” loop. It was built in 1961 to make backcountry an alluring destination for tourists, offering stunning wilderness vistas but also creature comforts like showers and reasonably comfy beds.

Arras told her father that she wanted to photograph a nearby lake. It wasn’t terribly far, just over a bluff. He declined to accompany his daughter, 14 at the time, but an elderly man from their group would tag along. At some point, the 77-year-old man grew tired, and sat down to rest. Arras, seemingly determined to reach the water, trekked onward.

Back at the camp, the group’s tour guide remembered noticing her from afar. She was “standing on a rock about 50 yards south of the trail.” According to a summary of her official cold case file, that was the last time anyone saw Arras—or the last time anyone is known to have seen her. She vanished that day, without a trace, leaving only her camera lens behind.

*

Search-and-rescue teams eventually stopped looking for Arras. But that hasn’t stopped her case from finding new life. Today, the teenager is well-known among paranormal enthusiasts. Her disappearance, and hundreds of others, comprise a strange portfolio of “mysterious” national park vanishings, loosely tied together by a few common—and dubiously supernatural—themes.

The genesis of this movement belongs to David Paulides, a cryptozoologist with a self-described “law enforcement and investigative background.” (I was unable to independently verify this.) Paulides created the Missing 411 books and documentary, which chronicle allegedly preternatural disappearances in or near national parks.

In his first book, Missing 411 – Western United States & Canada: Unexplained Disappearances of North Americans that have never been solved, Paulides recalls a conversation he claims to have had with a national park ranger:

I sat in my room at the lodge and listened to the ranger tell me about a series of missing people inside our national parks. The ranger stated that the events were very unusual, many people were never found, and the park service was doing everything possible to keep a lid on the publicity surrounding the missing. He explained that non-law enforcement employees weren’t privy to all the information, but that the upper-echelon law enforcement supervisors inside the park service were concerned about the numbers and certain facts surrounding specific cases.

It was a pivotal moment for the author, who is now in his mid-70s. Paulides has become the foremost expert in national park disappearances. He claims to have spent 7,000 hours researching cases like Arras’—interviewing families, law enforcement, and search-and-rescue personnel; poring over newspaper archives; and submitting hundreds of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

The thing is, Paulides is also a Bigfoot chaser. And he’s seemingly allowed his work to become paranormal fodder, quite possibly because he thinks Bigfoot, or something else, is abducting people.

When he isn’t investigating missing persons, Paulides works on the North American Bigfoot Search, a group he founded to legitimize the cryptid’s existence. In 2013, Paulides submitted a FOIA request to the National Park Service for records related to two missing hikers in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. “Associated with possible Bigfoot abduction,” his FOIA request noted.

In his 2016 documentary, Missing 411, we hear Paulides speaking on Coast to Coast AM, a paranormal radio talk-show.

“We plunge once again into the deep end of the paranormal pool. Hundreds of people vanish from our national parks and forests…under very unusual, but very similar circumstances,” the show’s host, George Knapp, says to Paulides, who I was unable to speak to for this story due to scheduling conflicts.

“It’s like he’s plucked out of the sky,” Knapp remarks about a missing child. “Snatched out of the sky.”

The bedrock of Paulides’ implied thesis—that something sinister, even supernatural, is happening to missing persons inside of national parks—is what he calls “clusters.” These alleged commonalities in time, place, and circumstance of North American disappearances, he claims, are clues to a larger mystery.

Some clusters, like people vanishing near water, are unremarkable. Water-related accidents are a common cause of death in the outdoors. Drowning has remained the number one cause of death in national parks over the last decade, after all.

“People wander into these areas, and there are so many places, and so many ways you can disappear”

Other clusters, however, are wildly bizarre.

Paulides has described people “melting” into their clothing. He posits that children with “disabilities” are overrepresented among the vanished. And that storms inexplicably tend to hit after someone has gone missing. (In Arras’ case, it should be noted, investigators said at the time that unusually arid summer weather may have thwarted scent dogs’ sniffing capabilities, due to dry and dusty conditions.)

“People disappear and are found in the middle of berry bushes,” Paulides writes. “They go missing while picking berries; and some are found while eating berries. The connection between some disappearances and berries cannot be denied.”

Paulides never explains what these clusters mean, or what’s causing so many people to vanish. An expansive story recently published in Outside puts that number at 1,600 individuals. (This estimate is based on Paulides’ research, and includes missing persons on all public lands; approximately 640 million acres, or 28 percent of land in the United States.)

But despite the supernatural undertones, Paulides did discover something spooky. Something more disturbing than a mythical man-ape stealing children from their parents: The National Park Service doesn’t keep track of missing persons. It doesn’t know how many individuals have disappeared in its parks. If you were to ask, they’d tell you, “We don’t know.”

And that’s exactly what happened to me.

Paulides exposed this fact in his documentary, Missing 411. During an interview with then-Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar, who oversaw the National Park Service, he asked that same question. How many people have gone missing from national parks? “I don’t recall,” Salazar replied, visibly uncomfortable.

I submitted a FOIA request to the National Park Service for that list, hoping to corroborate Paulides’ exchange with Salazar. The agency told me that no responsive records exist.

“Please know that we reached out to and collaborated with other offices/bureaus: The Office of Law Enforcement & Security, BLM [Bureau of Land Management], and NPS. According to the feedback we received, they do not track or maintain listings of missing persons,” a National Park Service FOIA officer told me in an email.

It’s also prohibitively onerous to see incident reports (records that document accidents, injuries, and fatalities in national parks) that predate 2013.

Once, I asked for reports concerning geyser accidents at Yellowstone National Park, and was told it would require “a hand search of records in multiple locations for all years prior to 2013, when the park transitioned to an online reporting system, the Incident Management, Analysis and Reporting System (IMARS),” by a FOIA officer.

Paulides’ revelation kickstarted a petition to force the National Park Service to keep such a list. A database like the publicly accessible National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), which is maintained by the Department of Justice, could theoretically help these cases find closure.

Neither the Interior Department nor the National Park Service responded to a request for comment.

“[National] parks are complicated. People wander into these areas, and there are so many places, and so many ways you can disappear,” Todd Matthews, Director of Case Management and Communications for NamUs, told me.

But unlike NamUs, which is a clearinghouse for existing missing persons data—aggregating police files, medical and coroner records, fingerprints, photos, DNA, and more—there’s nothing compelling the National Park Service to even generate a missing persons record.

“Sometimes the park service are the people managing the case,” and sometimes they’re not, Matthews noted. “They decide on own who’s going to be the case manager,” and often it ends up being local law enforcement.

“Allowing the public some degree of access,” is important, he added. “But crowdsourcing can be kind of sticky. We ask for social media help but we try to be careful, because you have a lot of cybersleuths out there. It’s not a game of making wild guesses.”

*

In 2011, Paulides submitted a FOIA request to the National Park Service for Arras’ case file. He was granted a few records, which he appealed, saying the agency egregiously withheld facts about the girl’s disappearance. His appeal was denied, and the National Park Service refused to release additional records, as they were part of an ongoing investigation.

He later claimed the agency hasn’t “looked at her case in 25 years.”

Paulides has portrayed the National Park Service as secretive and corrupt. It’s true it may be secretive, but it could be that the agency is also just astoundingly inefficient. We don’t know why the National Park Service doesn’t keep track of missing persons. But a major reason could be its law enforcement database.

“The whole system needs to be thrown into the digital dumpster and rebuilt”

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, the agency put IMARS—its digital database for incident and criminal reports—into motion. It cost taxpayers $15 million, and was meant to streamline crime reporting. Before this, records were kept in boxes, on paper. If someone wanted to see a case file, a records clerk would have to sift through them.

“When fully established, IMARS would enable all Interior law enforcement agencies to use a common, Department-wide reporting and records management system that can provide secure, accurate, reliable and timely law enforcement information necessary to more effectively carry out Interior’s public safety, homeland security, and resource protection missions,” a press release said.

Today, IMARS is notoriously loathed by government staff. It’s allegedly buggy, and poorly made. It has a tendency to create duplicate entries, and is tedious to search. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has entirely refused to use it, saying it doesn’t interface with other crime databases.

“The whole system needs to be thrown into the digital dumpster and rebuilt,” an Interior Department law enforcement officer who requested anonymity told me. “The technical side sucks and is less than intuitive, but the accountability is shoved onto street-level supervisors to check that people are doing their jobs.”

“None of it is automated,” they said. “Adding to that, every park is its own special, semi-autonomous fiefdom,” they said.

In other words, each park can decide who will lead a missing persons case. If that ends up being local law enforcement, that’s usually where the records will be.

A spokesperson for a major national park once told me it wasn’t their responsibility to keep such files. I had asked for a list of missing persons there, and my question seemed to baffle them. Obviously, I should go to the sheriff’s office, they said. They weren’t evasive about telling me this—it just wasn’t their problem.

“There’s never been a push from the Interior Department to say, ‘this is what your rangers do. They need to document X, Y, and Z,’” the law enforcement official added.

*

What makes Paulides’ ideas so tantalizing, so salacious, is what he doesn’t say. He denies mentioning Bigfoot in any of his works. But, like a good storyteller, he allows readers to reach these conclusions on their own. Even his fans have questioned his motives.

“I do find David to, at times, sound a little bit like a charlatan,” one wrote on Reddit. “I feel like when you get so invested in something you are bound to lose yourself a little bit.”

“Paulides’ is being deliberately vague about what he thinks because he doesn’t think there is anything going on, but, he’s got books and tickets to sell,” wrote another.

“It seems like he thinks it’s some sort of extra-dimensional being, but isn’t exactly sure what. I could be wrong though because he is often vague,” another person observed.

“I don’t think you are wrong,” someone else replied. “I feel like he often (vaguely as you said) seems to point in that direction too.”

It’s also deceptively easy to get lost outdoors. There are countless ways to become disoriented, hurt, and killed. Panicked humans do incomprehensible things, like paradoxically undressing in freezing temperatures—a phenomenon that could explain why missing people sometimes remove their clothes.

And the wilderness can be eerie. Backcountry is almost otherworldly, devoid of sights and sounds that remind us we’re safe. When a person can’t assign a logical explanation to something, like an animal call, their mind starts filling in the blanks.

Paulides has taken advantage of this. But is it good marketing, or predatory spinning? Does it do justice to grieving families, or does it rob them of an earnest conversation about their missing loved ones?

As for what happened to Arras that day, there are plenty of theories. But no definitive answers.

Could she have crossed paths with a mountain lion? Surely, someone would have heard her scream.

Did she fall, and slip between some rocks? Search-and-rescue looked everywhere.

Or was her disappearance a homicide? According to the elderly man who accompanied her, there was allegedly another group of hikers nearby.

Arras is a cold case now. Unlike other missing children in more recent times, she’s not memorialized on a website or on Facebook. Yet, people haven’t forgotten her. And Paulides gets credit for that.

It’s a strange compromise—to be remembered as an X-File—but maybe that’s what it takes. Maybe, soon, the National Park Service will dust off these records and make them public. There, they’re likely to seem a lot less mysterious, as all things are when brought into the light.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.