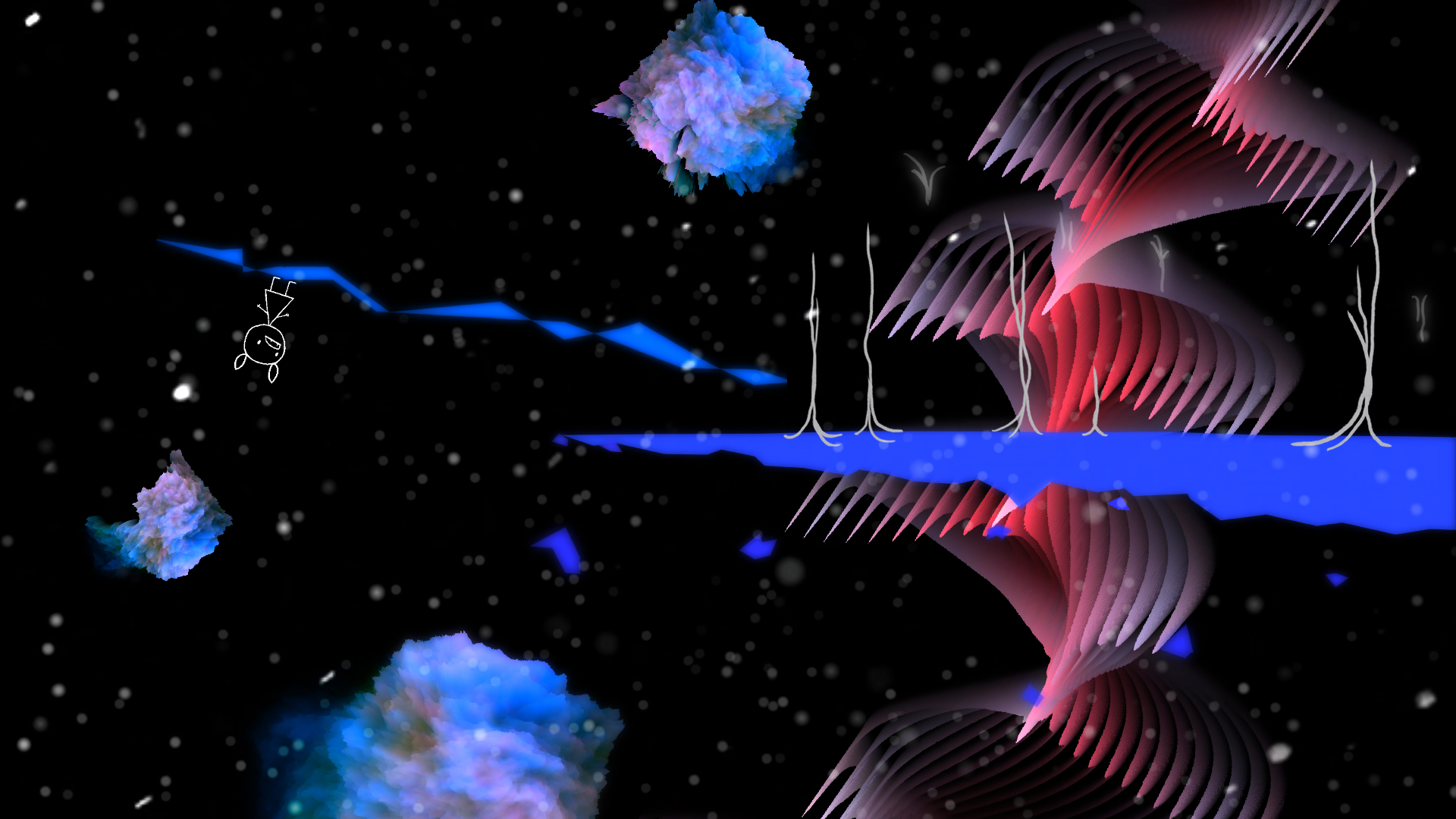

After two years in the trenches, cult animation legend Don Hertzfeldt—who’s directed, animated, and funded his own movies for over 20 years—has released a melancholic, joyful, surreal, complex new short film called ” World of Tomorrow 2: The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts.” It’s a beautifully rendered mix of hand-drawn aesthetics and computer-generated weirdness.

Equal parts Bicentennial Man, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Rick and Morty (only with women as main characters), “World of Tomorrow 2” tells the story of a sixth-generation clone who travels hundreds of years into the past to give her six-year-old original self a tour of humanity’s remains after the end of the world. “Emily Prime” is a young, pure, undamaged version of Emily 6 (Julia Pott), who thinks her younger self can make her feel whole. In other words, this movie is too real.

Videos by VICE

“World of Tomorrow 2” is as mind-bending as it is heart-wrenching; at one point, the clone transports Emily Prime into her own psyche, which has been drained of hope by the isolation many clones face in Hertzfeldt’s bleak vision of tomorrow. Together, they navigate the garbled memories of her incomprehensibly sad life. Before a dark backdrop, Emily Prime babbles and asks naïve questions like the joy-filled kid she is, lending the film its funniest and most genuine moments.

Their conversations are pieced together from recordings of Hertzfeldt’s young niece Winona Mae, which gives the whole adventure a spontaneous feel that’s as quotable as Hertzfeldt’s classics. The script is improvised, which only works because Hertzfeldt is a lone wolf. “I like to have some fluidity in the thing if I’m going to be working on it for months or years,” he tells VICE. “I need to feel surprised and in the moment all the way through.”

The film screened at Sundance last week, but in his personal quest to fix the short film business, anyone can buy or rent it online. Shorts are regularly published online for free, which is “basically teaching an entire generation of artists that their work has no value,” he says. “We’ve all become spoiled as audiences, expecting everything to be free online all the time.” The sequel to his 2015 Oscar-nominated flick ” World of Tomorrow” is worth the cash.

Over the course of a dozen short films, Hertzfeldt’s wry absurdism and honesty has earned him a cult following. Longtime fans usually start with ” Rejected,” the iconic commercial parody known for lines like, “My spoon is too big!” and “My anus is bleeding!” It was nominated for an Oscar in 2000, went viral on early YouTube, and is widely regarded as one of the first essential 21st century animated shorts. Newcomers to his work likely found him through the wild Simpsons couch gag he directed, which is one of the longest and most surreal in the show’s 30-year run.

Part of the 41-year-old artist’s mystique is that he’s never done commercial work. A string of Pop-Tart ads cribbed his stick-figure aesthetic and dark humor in the mid-aughts. Hertzfeldt didn’t see a dime, was not pleased, and unlike many professional animators, hasn’t touched the advertising industry since. “Art is anything artificial that is intended to create an emotional response. It doesn’t even have to achieve it,” he says. “Advertisements would fit that criteria—lots of things would—but just because something can be called art doesn’t automatically mean it’s good art.”

His independence is the result of his cult following, and his cult following is the result of his independence. Which came first is a chicken-and-egg enigma, but his advice for artists who want to steer clear of the mad men echoes Tim Kreider in the New York Times, sci-fi author Harlan Ellison in the documentary Dreams Without Teeth, Star Trek alum and nerd influencer Wil Wheaton, the Oatmeal in comic form, and countless memes and thinkpieces. “Stop giving everything away,” he explains. “Exposure is useless if you never get paid. It’s not a bad or shameful thing to be paid.”

All of his films are made from the funds of fans purchasing his other movies. He hasn’t taken money from studios or even grants, and he wants to more of this model. “We have to reprogram audiences to actually support the things that they want to see more of,” he says. “Imagine asking a plumber to come fix your pipes, except you’re not going to pay him, you’ll just give him great exposure and a nice review. You’d get punched in the face.”

He’s been able to commit to this model because he animates alone. Previous to “World of Tomorrow,” he exclusively used an old analogue animation machine like the ones that made Disney classics; like a monk, he seals himself away for years at a time and occasionally returns to show the world something wonderful. Most animated movies today are produced by a small army of software specialists who work together like an orchestra: one team creates characters, another the backgrounds, or the lighting, or the animation, each layer building toward a final product like a beautiful symphony. Hertzfeldt takes the stage with nothing but a guitar and delivers an unforgettable performance every time.

Solitude and focus are key to his consistent output. When Hertzfeldt animates, he listens to music. When he’s recording and editing sound, he hears nothing but the film. He finds drugs and alcohol to be incompatible with his work. He even refuses to let the news cycle be a distraction. “The garbage fire helps,” he says. “If the world was perfect, I guess we wouldn’t have to try and make art.”

He also can’t recall ever having writer’s block. “Getting through the boring stuff is almost always the difference between a project existing or not existing,” he says. “Even if you’re Mozart and blessed with endless wonderful ideas all the time, you still have to sit down with a pen every night and correctly transcribe every single note for every single instrument in every single scene in the opera. The drudgery is the hard part and it’s when most people give up.”

But for more artists to even afford the opportunity for tedious, lonely labor, the market has to change. “Every time you pay to watch something you’re casting a vote. You’re saying, ‘Hey go make more of this, please.’ Audiences have all of the power to shape what gets made and what doesn’t.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

More

From VICE

-

Everett Collection / Netflix. -

Vinay Gupta: "People are too stupid to understand they're being handed a solution" -

-