For decades, Haiti has endured coups d’états, authoritarian governments, complex political conflicts, and international interventions that have left behind weak institutions incapable of providing the basic needs of its people. The fragility of the country has forced thousands of Haitians to migrate in search of better living conditions. Most recently, massive displacement have been caused by both the 2010 earthquake that destroyed Port-au-Prince and the cholera epidemic that was brought over by UN peacekeepers and is responsible for 10,000 fatalities.

Many Haitians have immigrated to Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, Ecuador, and the United States. None of these countries have accepted them under the international legal definition for a refugee. The US, however, has offered them a temporary protection status, and Brazil continues to grant them a humanitarian visa, allowing them a stay in the country, but with limited protection compared to a refugee.

Videos by VICE

In Brazil, many initially found work in construction, building the infrastructure for the 2014 Soccer World Championships and then the 2016 Summer Olympics. Meanwhile, youngsters attended local universities, and the service industry employed many women. By spring 2016, the first wave of Haitians coming from Brazil began to arrive at the southwestern border between the US and Mexico. Later that year, after the Olympics finished and the Senate impeached President Dilma Rousseff, more Haitians left, seeking entrance into the US. Most ended up in border cities like Tijuana, Mexicali, and Nogales, overwhelming local shelters. The Mexican government opened its doors to all and coordinated with US migration authorities to keep those crossing to a limited number. However, the burden of maintenance, food, and housing costs during the waiting period in these Mexican cities fell to local municipal and state offices, as well as NGOs, churches, and others offering private donations.

According to César Anibal Palencia Chávez from the Tijuana Municipal Migration Affairs Office, close to 4,000 Haitians were distributed among 27 shelters in the city, and slightly fewer were in the neighboring Mexicali, awaiting a date to cross into the US in December 2016. By the end of the month, those who arrived were told they would have to wait up to five months.

The photographs below show the everyday lives of Haitians stuck in Tijuana. Some look for work to earn a few extra pesos; others constantly worry about what to wear, hoping to always look sharp, should they get tapped on the shoulder and granted entry into America. Not all of the shelters are able to maintain the standards they want. Temporary shelters now include a church where 300 migrants sleep on the floor and one that had to acquire 70 additional tents for 200 migrants, when it initially expected to only hold 45 people.

And the general situation is getting worse. Trump’s immigration issues with Mexico have created further uncertainty, making an already urgent situation even more dire.

All photographs are by Hans Museilik. You can follow his work here.

A migrant holds his son, John Wesley, in his arms while he tries to get into the US at the international crossing station of “El Chaparral.” Every day, dozens of Haitians meet at this gate but are not allowed to cross.

A panoramic view of Tijuana’s downtown with the arc and the existing US border wall in the background. Tijuana is a cultural melting pot of thousands of migrants form all over the world.

A Haitian migrant steps out of his tent at the “Juventud 2000” shelter. After the arrival of thousands of Haitian refugees, concerned citizens created small camps in patios and inside churches. More than 27 temporary locations now offer shelter to these migrants, and this one in particular had to acquire more than 70 tents for them to sleep in. In contrast to Central American and Mexican migrants who rest at the border shelters for a few days and then jump the “line” into the US, Haitians have to wait for up to five months to be able to present themselves for an interview with US immigration officials.

A Haitian migrant leans against the US-Mexico border wall, listening to some stranger that started talking to him in French. The Friendship Park in Tijuana is the only place where divided families by the wall can actually speak and (sort of) see one another on weekends.

A Haitian migrant gives another companion a haircut outside a shelter.

A group of Haitian migrants play dominoes in a room under construction at a Christian church that’s giving them shelter. This is just one way that they kill time while waiting to cross the border.

Two Haitian migrants help build a kitchen.

Tijuana, Mexico. Posters of House Rules at the “Casa del Migrante” shelter in different languages, including French. Ever since the wave of Haitians and migrants from African countries, shelters had totranslate information into French.

As part of the Christmas celebrations at the “Casa del Migrante” shelter, a man breaks a piñata with a stick. Different volunteers donated food and presents, so migrants and deportees, regardless of their nationality, had good time over the holiday.

During a Christmas celebration at the “Casa del Migrante” shelter, a Haitian migrant shows his enthusiasm after receiving a gift.

Dozens of Haitian women and children share the old section of the a church, which not only serves as a huge dormitory but also as a playground for all the children.

December 28, 2016. Tijuana, Mexico. A Haitian woman and her child, carefully walking through a construction site, pass other Haitians who are busy erecting a plaster wall. Long waiting periods for their US-entry date push migrants to start seeking local jobs.

A Haitian child tries to grab the photographer’s camera.

Another Haitian migrant dictates a text into his smartphone. Finding sleeping accommodations is not an easy task, and the quality always varies in these shelters. Some find beds, while others have to sleep in tents that offer scarce protection from rain and cold during the winter.

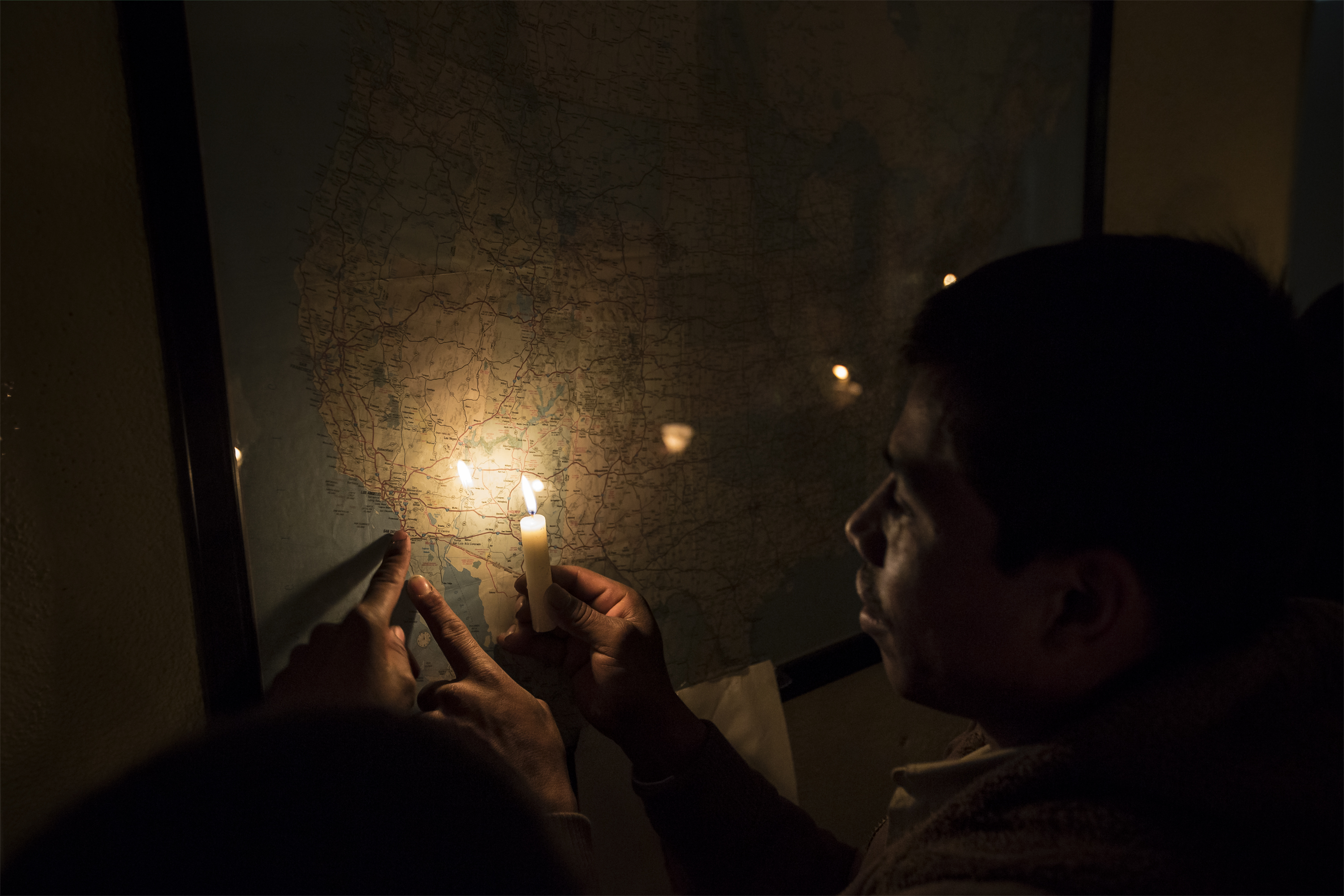

A couple of Central American migrants check out their planned route into the US on a map while holding candles during the traditional Mexican Christmas celebrations. Haitians comprise almost 80 percent of the shelters in Tijuana, but there are still some from elsewhere.

During a street celebration in front of one of the shelters, a Haitian migrant dances with a local girl who was volunteering. Different Christian groups or concerned neighbors would drop by the shelters and donate food, clothes, or even services, like a free haircut.

During lunch, food is served through a kitchen window at “Juventud 2000.” Since most of the migrants are from Haiti, Haitian cooks took over the kitchen and started preparing home-style chicken.

A father feeds his baby on a clearing outside the shelter. Many migrants from Haiti came with children born in Brazil. Some women even did the trip pregnant and gave birth in Mexico.

A few Haitian migrants warm themselves up near a fire on a dirt soccer field.