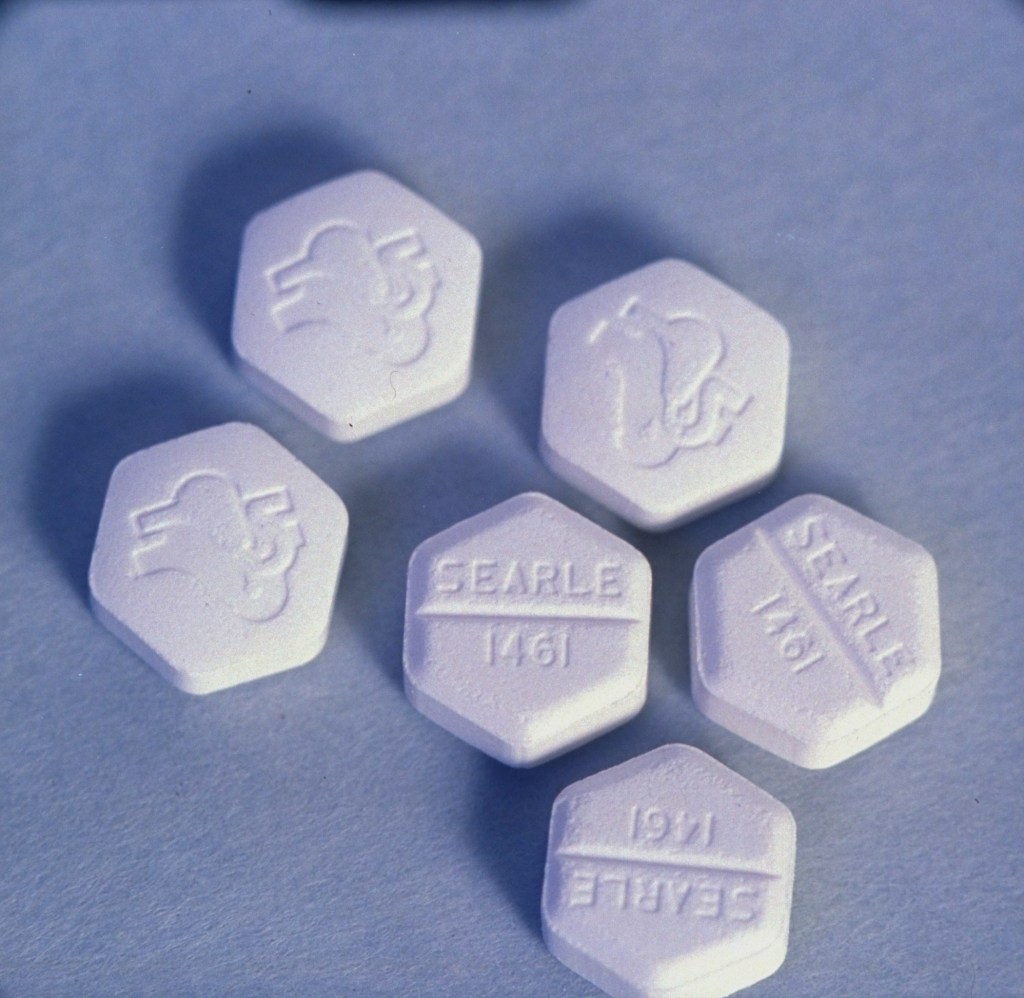

For years, anti-choice advocates have promoted the unfounded idea that medication abortions can be “reversed” halfway through the procedure. If a patient changes their mind after taking the first abortifacient drug—mifepristone—they can forego the second, misoprostol, and instead take several doses of progesterone to continue the pregnancy, according to the theory.

This claim hasn’t just been promoted through anti-abortion activism and crisis pregnancy centers, but legislated, too: Currently, six states—Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, South Dakota, Utah, and Virginia—have laws requiring providers to inform patients that they can request this “abortion reversal” treatment should they have misgivings about their decision to terminate, a phenomenon that is exceedingly rare.

Videos by VICE

While doctors have long contended that “abortion reversal” is nothing more than a myth intended to stigmatize the procedure, up until recently the treatment remained virtually untested. Now, new evidence shows that attempting abortion reversal can result in severe blood loss that could be life-threatening.

The findings are the result of the first-ever randomized, controlled clinical study on abortion reversal, conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis, and published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Originally, researchers set out to enroll 40 women in the study, who were already scheduled to have in-clinic abortions and consented to delaying the procedure for two weeks to test the abortion reversal method. These women would take a dose of mifepristone and then follow it up with either a placebo or progesterone. But researchers halted the study prematurely, after just 12 participants had been enrolled, when three women experienced vaginal hemorrhaging, or excessive bleeding, and needed to be taken to the ER via ambulance; one woman needed a blood transfusion. Two of them had received the placebo, and the other had received doses of progesterone. (On its own, mifepristone only stops the embryo from developing, while misoprostol is necessary to initiate uterine contractions to expel the pregnancy.)

Mitchell Creinin, the study’s lead researcher and a professor in the Obstetrics and Gynecology department at UC Davis, said that though his paper doesn’t definitively debunk abortion reversal as ineffective, it shows that there are serious risks associated with not following through with the two-drug medication abortion regimen once it’s begun.

“We don’t have any evidence that disproves the possibility that abortion reversal exists,” Creinin said. “But I do have evidence that not completing the regimen as it’s designed is dangerous.” The study concludes by recommending that states stop passing laws that require providers to discuss abortion reversal with patients: For now, the treatment remains experimental and “and should be offered only in institutional review board–approved human clinical trials to ensure proper oversight.”

“Laws should not mandate counseling or provision of any treatment when we do not fully understand treatment efficacy (including best route of administration, dose, and duration) and safety,” the paper reads.

A self-described “pro-life” doctor, George Delgado, originated the idea of abortion reversal in 2012, when he claimed he’d discovered a method for chemically reversing the effects of mifepristone. The drug blocks the hormone progesterone, which is necessary for continuing a pregnancy. In a co-authored report at the time, Delgado said he had helped six pregnant women who had initiated a medication abortion carry their pregnancies to term by giving them injections of progesterone in the 24 hours after they took the mifepristone pills.

Ever since, anti-choice advocates have used Delgado’s claims to suggest that science supports the idea that abortions can be reversed. But Creinin and other experts say Delgado’s findings are based on bad science: Delgado didn’t use a placebo as a control, nor did he randomize the study. What he produced was merely a series of case reports, Creinin said, which fail to prove a cause-and-effect relationship between post-mifepristone progesterone injections and continuing a pregnancy. (Delgado told VICE News in April that he plans on conducting another study that will include 900 women, though he still will not give any of the women a placebo as a control.)

There was “zero evidence” that such a thing as “abortion reversal” worked, Creinin said, but because Delgado’s claims had resulted in multiple state laws, he felt he had a duty to put them to the test.

“The lack of evidence hasn’t stopped people from passing these laws, so we wanted to take the question seriously, in a rigorous, controlled trial with Institutional Review Board approval,” he continued. “Patients deserve the truth.”

Reproductive health advocates say the requirement that abortion providers in some states must inform patients of a reversal protocol that isn’t supported by evidence is just one way anti-choice legislating infringes on the doctor-patient relationship. Five states mandate that providers tell patients that there is a link between abortion and breast cancer, a claim that has been widely discredited, and eight of the 23 states that require providers to inform patients of possible psychological responses to having an abortion emphasize negative outcomes, like depression and anxiety, which studies have shown are not caused by abortion.

“[Abortion reversal] goes beyond laws that force providers to give information about unproven or disproven claims, like that abortion causes depression or breast cancer,” said Daniel Grossman, the director of Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), a program at the University of California, San Francisco. Laws requiring doctors to inform their patients of abortion reversal “encourage patients to essentially participate in an unmonitored experiment. This latest study suggests there are actual safety concerns surrounding that.”

Creinin said it’s important to emphasize that the dangers associated with attempting to reverse a medication abortion don’t diminish the overwhelming safety and effectiveness of medication abortion itself, which has decades of research to back it up. In 2017, almost 40 percent—or nearly 2 in 5—abortions were done with pills.

The key is that medication abortion requires both medications, he said, which has been the official recommendation of organizations like the World Health Organization, the Food and Drug Administration, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for decades.

“Medication abortion, performed through a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, has provided a safe, effective option for induced abortion that has benefitted millions of women,” said Chris Zahn, the vice president of practice activities at ACOG, which publishes the journal in which the study appears. “Even with its limitations, [Creinin’s] study raises safety concerns about not completing the evidence-based regimen. Mifepristone is not intended to be used without follow-up misoprostol treatment.”

Still, it’s unlikely that Creinin’s finding will change the minds of abortion opponents, who are likely to continue citing Delgado’s ongoing research, despite its flawed methodology. Several more states (including Georgia, Kansas, North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin) have abortion reversal bills working their way through the legislature, and similar federal legislation—called the “Second Chance at Life Act”—was introduced in the House in April.

But while Creinin’s study isn’t definitive, since it had to conclude early, he’s come to the end of his research. The first step of any series of studies is to establish safety, he said—if this had been, say, a clinical trial for a new birth control pill, the negative outcomes the participants experienced would preclude the possibility of continuing to research it.

“You study something when there’s a reason to study it, and we have no evidence that suggests abortion reversal is real, while we do have evidence that it’s potentially dangerous,” Creinin said. “So if I were developing a drug I would say, ‘I have to stop.’”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Marie Solis on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Kinga Krzeminska/Getty Images -

-

Pico/Getty Images -

Francis Specker/CBS via Getty Images