Spoiler warning: story spoilers ahead for Another Lost Phone and the sequel, Laura’s Story. Content warning: this piece contains personal, frank discussion of abuse and mental health issues.

There is no snappy intro for an article about abuse. It’s not a life lesson, or a good anecdote; It’s a scar that you didn’t notice forming until it was too late, and now it sits on your skin, reminding you of what happened every now and again, an itch you can’t scratch.

Videos by VICE

Every now and again, something will bump that scar, triggering a stab of pain and reminding you of how you got there in the first place. I just finished Another Lost Phone: Laura’s Story, the sequel to A Normal Lost Phone, and I had to take a break afterwards to let my scattered, sudden reaction to the intimate depiction of abuse sink in and develop into something manageable.

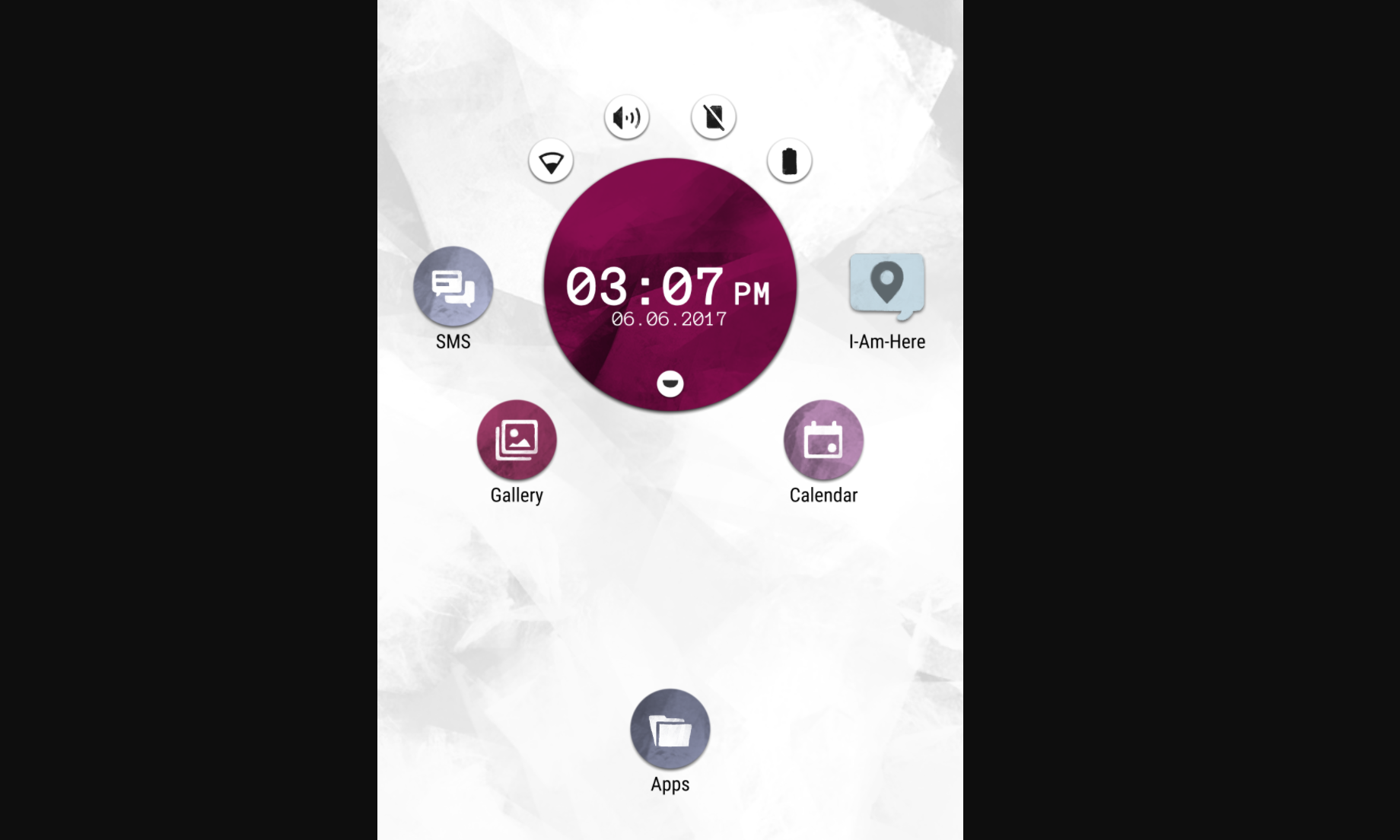

Like its predecessor, Laura’s Story takes place within the interface of a “lost phone,” and through some slightly unpleasant snooping—which the game warns you against doing in real life—you uncover the real story behind this person’s life, as told through their texts, emails, notes and photos.

A Normal Lost Phone was a tale of a transwoman struggling to come out, but, inadvisably, this aspect of the story was treated as a sort of plot twist. Here was a person who had escaped a life where people were mistreating her, only to have you do the same by snooping through her things and sending a photo of her to a stranger. Her struggle is treated as little more than a story beat, which doesn’t sit well in a world where real people are killed because they are trans.

Laura’s Story is handled more sensitively, telling a story about someone who slowly discovers their relationship is not the fairytale they thought it was. You do not send messages, this time, without the character’s explicit consent. It’s clear that the mistakes of the first have had a real effect on how they have handled the telling of Laura’s story. To go through someone’s phone to find out that they’re trans is, fundamentally, not your business. To do the same to find out if someone’s being abused—well, it’s still not your business, but at least it opens up the possibility of being able to help.

You, in the fiction of this universe, have found Laura’s phone several months after she first meets Ben, her boyfriend. You read through her messages, uncovering what at first seems like a concerned partner, but soon evolves into something much more sinister as he starts to invade and control all aspects of her personal life.

you are taken on the ride of slow realization along with Laura

Because this narrative unfolds in a somewhat linear way (thanks to having to find out various passwords to unlock more messages), you are taken on the ride of slow realization along with Laura. People don’t usually recognize abusive behavior when it first appears, nor the second, third, or fourth time. It takes several friends to contact Laura outside of her usual methods of chat, and in slightly insidious ways (one in particular pretends to be interested in hiring her just to get to talk to her) because they know it’s difficult to get around someone so controlling.

Even so, many of Laura’s friends are fooled by Ben’s behavior, telling Laura that his possessiveness and jealousy is “normal guy stuff.” Ben is a typical emotional abuser, using manipulation, isolation and gaslighting to get Laura to depend on him, but because many of these techniques are glorified by movies and books like Twilight and Fifty Shades of Grey, it’s often hard to accept that they are not normal behaviors.

But abuse happens in many different ways, and a game doesn’t have to reflect your exact experience to help you realize that your situation is similar.

I’ve been puzzling over my old relationships for a while now, as I spent most of the last year being single. Why did they end? What did I do wrong? What did I learn? Playing Laura’s Story brought some of those experiences into sharper focus, allowing me to see them for what they really were: toxic. A relationship does not have to align with the kind of abuse you see on TV—black eyes and belts—to be toxic. Laura’s Story does not begin as a story about abuse, and it is not immediately obvious until pointed out late in the game by Laura’s friend. Sometimes abuse is easy to categorize. Other times, it is not.

One of my first boyfriends was obviously abusive. He would lie to me about where he was because he didn’t want to see me, and burned me with a lighter for fun.

anyone who will take advantage of their size or strength against you, whether or not they physically hurt you, is abusive

But just like Laura, I dated people who were not necessarily the textbook, obvious versions of abusive, and it is those relationships that seemed normal to me for a long time. Being able to see other tales of toxic relationships, like Laura’s, outlines three important facts: Firstly, you do not have to stay in a relationship that makes you unhappy just because you love someone. Secondly, abuse is a much more nebulous and insidious thing than most people realize. Thirdly, anyone who will take advantage of their size or strength against you, whether or not they physically hurt you, is abusive.

My first long-term boyfriend would punch walls when he was angry, which terrified me. He once assaulted me when drunk because we had broken up and he wanted me back. He pinned me to a fence, away from my friends, and tearfully yelled at me until I had a panic attack, at which point he let me go. He later punched my friend who was trying to keep him away from me. I ended up going back to him, because it can be easy to dismiss behavior like that as “romantic” when you want to stay in love with someone, when you want to believe the best.

But later, I dated someone who, like the last one, was bad at controlling his anger. Even now I don’t want to say “he had anger issues” because I tried to tell him that at the time, and he got angry. I’m afraid he’ll read this, and get angry.

It’s hard to explain how much unchecked, unrestrained anger can feel like abuse when it’s entirely directed at you, because anger is something everyone feels from time to time. But that is exactly the point: abuse doesn’t always look like abuse to people on the outside. These were not one-off outbursts, these were repeated, incredibly unpleasant, hours-long sessions of anger that caused me intense emotional distress.

In Laura’s Story, her boyfriend Ben seemed kind and caring, slightly possessive but in a romantic way, and all of his little behavior quirks on their own could have seemed sweet. He worries about her when she’s gone for a couple of hours, he asks her to install a location app on her phone so he can make sure she’s safe, he tells her he doesn’t want to go out with her friends because he wants a night in, just the two of them. On their own, these incidents can be written off as one-offs. Together, they paint a picture of common abuse techniques to keep the victim dependent on the abuser.

There is one incident in my own relationship experience that sticks in my mind, that marked the turning point from seeing the angry behavior as one-offs and thinking “maybe this is normal,” to “this is a pattern, and it will keep happening, and get worse.”

I am anxious, and prone to panic attacks—especially in situations that remind me of being pinned to a fence. Any sudden movements, bodily restriction, or aggressive behavior towards or near me triggers those panic attacks. I don’t remember how this argument in particular began, but it was likely something I was worried about. Either way, it made him angry, and as the anger escalated, my actions went from rational to irrational and I started to become afraid. The angrier he got, the more he would gesticulate, flinging his hands up to illustrate a point. I asked him not to do that. He got angrier. The gestures got more exaggerated.

I flinched.

It was an instinctive response. He had never hit me, and never would in our whole relationship, but because aggression puts me in that anxious, high-adrenalin fight-or-flight response, I flinched.

“He yelled at me,” Laura says in a text to a friend. “He accused me of having a lover…and that I was locking my phone because I didn’t trust him.” Her friend questions this behavior. “It’s not normal, you know.” But Laura makes excuses for him. “Don’t you think it’s a mark of trust in the other person?”

In Laura’s Story, her partner makes sure that he is always the hurt party. She questions him about his abusive behaviors—even innocently—and he flies off the handle, accusing her of cheating on him, hiding things from him, not trusting him. And of course, because she loves him, she apologizes.

I flinched, and he looked hurt, wounded, like I was accusing him of physical abuse by my actions. I was cowering. I hadn’t realized. He asked me how I could even think, for a second, that he would do that. Not that he was sorry that he put me in that position, standing and yelling while I huddled in a corner on the bed. I was suddenly the attacker. So I apologized, over and over. I just wanted it to stop.

“He’s been deceived in the past and needs some reassurance,” Laura says. She is still making excuses, and what’s worse is that they’re “valid.” People who abuse love and trust always have valid excuses. Past trauma, alcohol, you. It’s never their fault.

After apologizing, it would always go the same way: we’d both end up sad, holding each other, maybe even crying, as he told me that he was sorry, it was just that he cared. It was worth it, I’d think, for this moment. Would I rather have a completely dispassionate relationship, or a tempestuous one that sometimes led to emotional reunions?

“He knows he’s too possessive,” Laura admits. “And he does apologize…he drinks a little too much to unwind, then says things he doesn’t really mean.”

Late in the game, you see that Laura starts listening to her friends. She goes to a conference about abuse, and notes down what the conference speakers say.

“Subtle mistreatment…is difficult to quantify,” her notes read. “It is subjective and depends on the level of sensitivity of each victim.” You don’t get to decide what level of abuse hurts you, how it hurts you, nor how long it hurts you for.

Stories have beginnings, middles, and ends; they have a neat narrative that wraps up by the time you’re done. But my story is not neat. It is not a good anecdote. There is no snappy beginning, and no real ending, and whatever semblance of a middle that exists is messy and without any sense of closure. But to read someone else’s experience, wrapped up as a narrative, concluded in a satisfying way, helps to put this tangle of feelings into a box—a box labelled “abuse.” It does not need to be followed by anything that lessens it, it does not need to be apologized for or explained, it just is.

I’m nowhere near my ending, not yet, because it’s hard to sift through the feelings and worries that come with experiencing something unpleasant. But even though Laura’s Story ends when you put the phone down, that doesn’t mean Laura’s story, lowercase, ends there too. Working through and past abuse is a much longer process, but this game helps with the most important and vital step: acknowledging and accepting that what you went through is real, even if it isn’t neat.

Once you’ve gone through that, you can write your own ending.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Xbox Game Studios -

Screenshot: Steel City Interactive -

VICE -