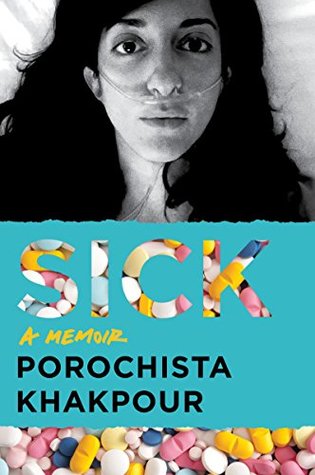

The book Sick begins with Porochista Khakpour’s most recent Lyme relapse, at the end of 2016, an episode of anxiety, depression, and insomnia that has become familiar enough to her that she can warn her friends and ask for their help. “It’s very reassuring to be around people when I’m confused. alone it is very hard.” Khakpour writes to them. “it’s hard to ask for help here because what can you do even? i don’t have the imagination to know what is help right now completely.”

Khakpour is a sufferer of “chronic Lyme,” a controversial condition the medical community has debated for years. Roughly 30,000 cases of Lyme disease, which is caused by bacteria from tick bites, are reported to the CDC each year in the United States, though studies estimate the actual number of Lyme incidences is closer to 300,000. It can be treated with antibiotics, but in some cases the symptoms persist in what is officially named Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS); experts tend to avoid the phrase chronic Lyme because it may be applied to people who never seemed to have Lyme to begin with. The cause of PTLDS is not completely known and there is no definitive test to prove that the bacteria is eradicated or that a person is cured. Worse, there are dishonest “Lyme literate” doctors who prey on the ill and charge people exorbitant sums for ineffective treatments. All of this makes chronic Lyme incredibly difficult to treat.

Videos by VICE

Khakpour doesn’t know when she was infected. Her memoir isn’t a convenient narrative of sliding from health to illness; she can’t remember a time she wasn’t in “mental or physical pain.” Her symptoms include dizziness and fainting, severe insomnia, constant aches and headaches, limping, inability to regulate temperature, dysphagia (inability to swallow), and complete disorientation. In Sick she recounts countless doctors misdiagnosing her with depression, anxiety, diabetes, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, to name just a sampling of conditions. “To pinpoint this disease, to define it, in and of itself,” Khakpour writes, “is something of a labor already.”

Khakpour was born in Tehran in 1978, an “infant of the Islamic Revolution and toddler of the Iran-Iraq War,” before migrating to Los Angeles as a young child. This is one of the many moves she makes—including stops in Santa Fe, Chicago, and New York—in the hopes of finding a cure. Sick is not organized by chronology, but rather by city and the lover who was is living with her at the time, linking illness to place and person. The constant is the racism Khakpour endures because she is a brown-skinned woman in post-9/11 America. Ironically, this racism only abets when she is at her most sick, and therefore most pale and white-passing.

As a result of chronic Lyme, Khakpour is constantly fighting against feeling alienated in her own body. “I was in it for the brain anyway,” Khakpour writes of her childhood. “So many books to write, so many to read, so many words to learn.” As she becomes more and more sick, Khakpour expresses a desire to “untangle from [her] own hopeless interiority” because “outside me there was all sorts of possibility; it was the inside that was the problem.” This is one of the greatest tragedies of her sickness: complete dislocation as a result of chronic illness and constant racial alienation. “Here was never a home for me outside as there was a home for me inside—my own body didn’t feel like my own,” Khakpour writes. “I sometimes wonder if I would have been less sick if I had a home.”

Khakpour’s mental and physical wellbeing are inexorably tied together—she notes that her flare-ups coincide with external political stressors, like the Paris attacks or Donald Trump’s election and his “Muslim ban” executive order. She has survived sexual and domestic assault, which she describes in her memoir with the type of nonchalant restraint that is born out of trauma’s normalization. Her slow trudge toward a diagnosis is a source of trauma in itself. After years of chronic pain and countless emergency room visits, Khakpour is told by a nurse, point blank, “Nothing is wrong with you physically, you need to understand that.” Eventually, she begins to believe it.

Fainting felt, just as Khakpour writes, “like the life force was being vacuumed out of me, from every orifice.”

The American healthcare system has well-documented habit of minimizing or ignoring female pain—according to a 2008 study from the National Institutes of Health , women have emergency wait times that are 16 mintues longer on average, and are prescribed opioids 13 to 25 percent less when experiencing pain. “Women suffer the most from Lyme.” Porochista Khakpour writes. “They are diagnosed the latest, as doctors often treat them as psychiatric cases first.” And just as women with Lyme may be misdiagnosed, women without Lyme may be incorrectly diagnosed with it: According to a 2009 study published in the Journal of Women’s Health, diseases with “a female preponderance”—like fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome—are often misdiagnosed as Lyme. The consequence is that women often don’t receive adequate treatment.

I have yet to meet a woman who doesn’t have a story about being ignored or dismissed by the medical system. Here’s mine: Sophomore year of college I spent a year and a half undergoing a battery of tests for chronic fatigue, depression, headaches, and muscle pain. It started with a fainting spell. At 4 AM I woke up to pee, and on my return trip I was forced to crawl down the hall as I repeatedly blacked out. Fainting felt, just as Khakpour writes, “like the life force was being vacuumed out of me, from every orifice.” At my college health center, I had to confirm I was not pregnant before receiving other care. I was then, of course, tested for mono. I demanded a thyroid test, as it ran in my family. This, and every other blood test, came up negative.

I spent the summer visiting my doctor to get to the bottom of my problems. For my depression, I was recommended to a behaviorist, but couldn’t get a referral to an in-network therapist. I was barred from getting a referral to a physical therapist for the pain in my knees—which I knew to be tendonitis after years of competitive volleyball—because my doctor decided that my additional aches meant I had fibromyalgia. I was told that I must attend a fibromyalgia clinic, which I did, but still never received the physical therapist referral. Repeatedly, I became someone else’s problem.

I was lucky—not only did I have insurance that gave me access to healthcare, eventually I figured out what was wrong. An acupuncturist recommended me a kidney ultrasound, which revealed a benign growth that may have been affecting my endocrine system. I was given an augmented diet, which made me realize that my remaining symptoms were from the eating disorder I had picked up from the anxiety of attempting to get adequate care. Reneging food made me feel powerful. Fasting was an honorable act, with religious connotations. Juice cleanses were trendy and people kept complimenting me for losing weight. More than anything, I at least had power over my body, my sickness.

Khakpour describes this sensation of being “intensely fragile yet ultimately indestructible,” and knowingly engaging in behaviors, like smoking and drinking, that have made her health far worse. Her memoir flirts with the idea that she is both a source and a victim of sickness. “If you know a part of you is always dying, taking charge of that dying has a feeling of empowerment,” Khakpour writes. “I am a sick girl. I know sickness. I live with it. In some ways, I keep myself sick.”

Khakpour’s lived experience echoes a bottomless trope in literature. In Leslie Jamison’s seminal 2014 essay, “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” she writes, “The moment we start talking about wounded women, we risk transforming their suffering from an aspect of the female experience into an element of the female constitution—perhaps its finest, frailest consummation.” Khakpour both embodies this figure—admiring her terminally ill aunt, who Khakpour describes as the “vaguely tragic and uncontainable and iconoclastic”—and bucks against it through writing about the intense difficulties of fighting for treatment.

This ultimately differentiates Khakpour’s illness memoir. Sick is not about the convalescent woman an object. It is about the ways our culture is at fault for putting her there in the first place—the American healthcare system is as culpable for Khakpour’s rapid decline as the tick that initially bit her.

It is remarkable that Khakpour managed to write this memoir despite her sickness, just as it is remarkable that such a small pest—a kaneh, as her parents call it in Farsi, a word that’s also an insult—could wreak such havoc. As she writes: “Of all of the things that could do damage—revolution, war, poverty in this new land—why would anyone think of a kaneh?”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Nicole Clark on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Anthony Franklin -

Photo by NYU Langone Staff -

WWE -