Trash-covered beaches, turtles asphyxiated by fluorescent pink drinking straws, and thick grey smog—these are the kinds of images we typically associate with pollution around the world. But what about the environmental contamination we can’t see? This is what photographer and activist J. Henry Fair sets out to capture.

With the help of a private pilot, Henry took to the skies to shoot Industrial Scars: a photography series which aims to show the industrial pollution that comes from our mass commercial consumption. He’s photographed petroleum drilling sites, paper manufacturers, animal farming, coal extraction, and plastic production—all of which have horrendous implications for the natural environment. VICE had a chat with him to learn more about his confronting photography and his environmental activism.

Videos by VICE

VICE: Hi Henry. Can you tell us a bit about what inspires your photography?

Henry: Today, people have placed themselves in echo chambers. These chambers are created by the algorithms of our socials, which feed us what we already think. What I’m hoping to do is make something so beautiful that it transcends these chambers. That is how I tap into people locked into those extreme ends where they don’t believe this is happening. The point is to start a dialogue. I’m not so hopeful that my one picture is enough to change their view entirely. Sometimes, all it does is prompt someone to start asking questions. Some young people do come up to me and say thanks to my images they have gone vegetarian, and I love that.

How did you find these places?

I keep databases. I track all of this stuff, I track locations. It’s a case by case scenario. After studying these for years, I have a really good idea of what is happening and where. I also choose on the basis of whether I am trying to influence legislation.

What issue are you currently trying to raise awareness about?

The discussion around coal in Germany, which is gaining momentum. I made German brown coal a big part of my latest exhibit because I wanted to influence the dialogue. People had no idea how much is being burned. A power plant burns a trainload of coal every day, and you make a tremendous amount of ash when you burn that coal. The largest cause of death in the EU is air pollution. And if we stop burning hydrocarbons we solve that problem. Climate change is the poster issue, but all these other problems are related.

So you want to show people what’s going on, and hopefully inspire them to act?

Yes. So currently, the Hambach forest is a big environmental issue in Germany. There have been activists living in the forest to protest its destruction for years, and they have been named lunatics when they have actually saved it from being destroyed for coal. This issue is symbolic and representative of both a European and wider global issue. Of the 10 largest carbon emitters in Europe, seven are coal power plants. So although an issue for the forest, which holds five European species, it’s representative of Germany’s policy with coal, because Germany is the largest carbon emitter in Europe.

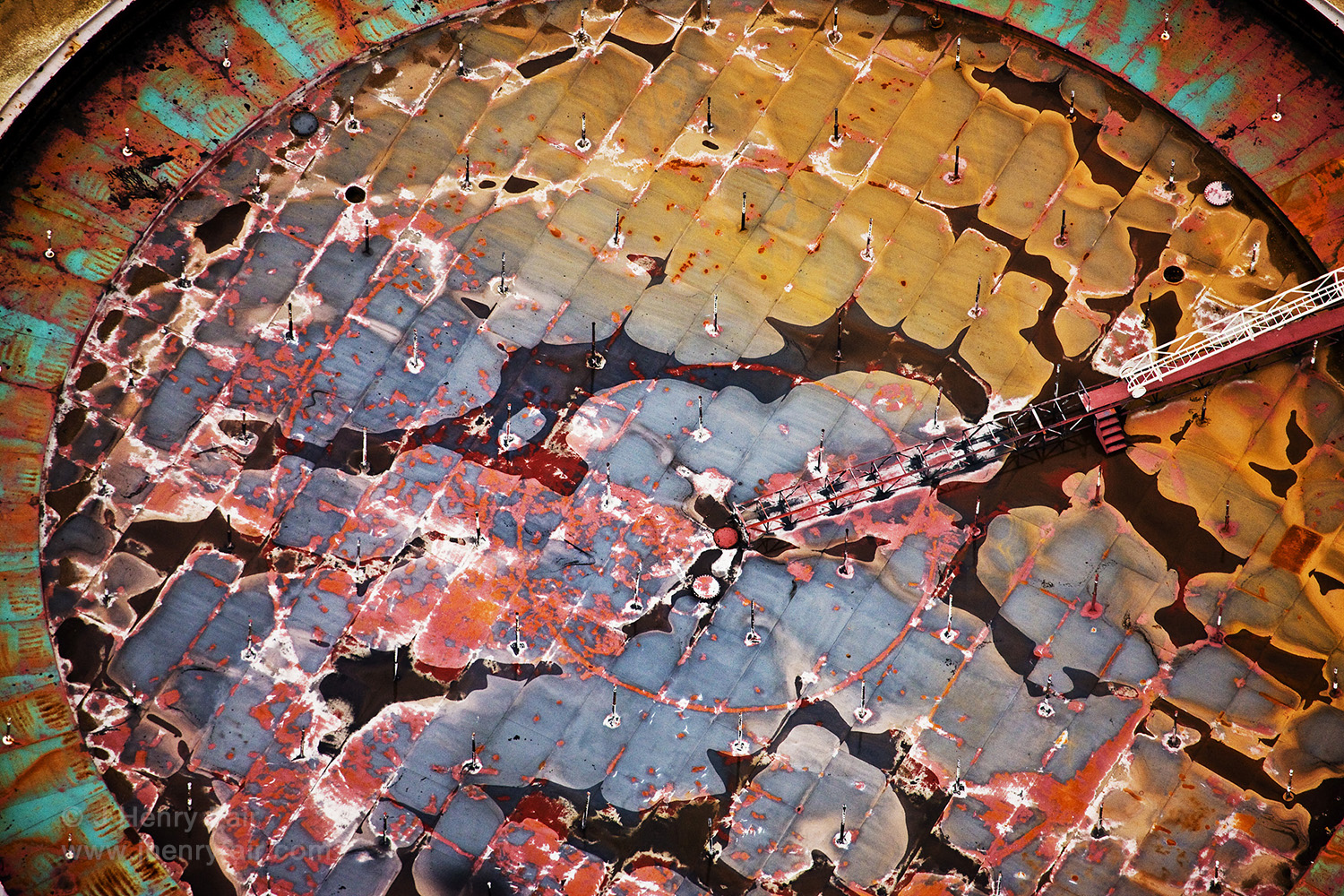

Tell me about the photo showing pollution that comes from making tissues in Canada?

What you are looking at is the waste from making the most popular brand of facial tissues and toilet paper. But I don’t want to tell people what brand it is; I’d rather tell them they need to use toilet paper made of newspaper instead. If you do that, you will save a forest in your lifetime and you will also do something big for climate change and water pollution.

What’s going on with the tissue production, and how does it work?

It’s in Canada and they’re cutting down the old boreal forest to do it. The bubbly things in the middle are agitators. They are agitating the liquid waste to speed evaporation of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and they put microbes in there to help eat up some of the organic matter. The agitation is speeding that process as well.

How does taking these photos impact you personally?

Well, I only just bought a smartphone during Christmas time because I had been resisting it for all these years, precisely because I didn’t want to get into that echo chamber our socials put us in. It was also because I know the environmental cost of those smartphones. That is one of the changes that my research has prompted in my life. I don’t eat much meat, because I know that eating meat is one of the most damaging things we do to the environment.

The main discovery I made is that environment means nature, and nature means us. Humans are nature. Let’s not forget that. The civilisation we have acquired makes us think that we are separate from nature, which is the most dangerous thing in the world.

Can you give me an idea of the scale of how big the land you photograph is?

It varies between photographs, but most are taken at about 300 meters high. You are looking straight down on a giant lake of toxic waste. They are all aerials.

How do you get to the altitude to capture these photos?

I hire pilots to get up there. I use the plane to get to about 300 meters, which is usually the minimum legal altitude over populated areas. Sometimes I can get a pilot to go lower. That is one of the hardest aspects of the production process, though: in many places, it’s really hard to find a pilot and a plane. In Singapore, for example, it’s impossible. Singapore produces a lot of oil rigs, so I was hoping to photograph those, but no one would take me.

Have you had any negative experiences while manoeuvring these environments?

I’ve had the FBI question me—they were very polite though. Generally, since the September 11 attacks, America has been particularly paranoid. Fear is such a useful emotion to generate in a population, which caused one of my pilots to report me for being a terrorist. “Keep people uneducated, keep people afraid” is the best formula that has worked throughout history to manipulate populations.

Another time a refinery called the police because they saw us flying above them. It was a very windy day, and I saw something I wanted to photograph. I’m usually using a telephoto lens to get those very interesting graphic images. Because photographing at that altitude is hard, and the wind was strong, the pilot was struggling to position the plane. Someone on the ground saw us circle the area many times and called the FBI.

Can you smell the pollution from that height?

Yeah, it’s horrible. If you are flying through the exhaust of a coal-fired power plant or a refinery, it’s so toxic. You can smell it from the plane.

What message do you want to send as an activist?

We are at a crisis. Our time is up. Now is the time when we must act, or no one else will. Governments don’t respond to people; governments respond to corporate owners. The capitalist model is about extraction, consumption, then disposal. The people that are making big money off that have children too, but lie to themselves and say their money will insulate them from the bad.

The polar bears are over already. Don’t cry for them. Same for tigers. There’s a lot that we’ve already lost—but we can still save a lot. The only way we can stop any more from happening is if people get out on the street, and say “no, we are not having this anymore.”

Find Edoardo on Twitter and Instagram

For more of J. Henry Fair’s work you can also find him on Twitter and Instagram