The 1990s were undoubtedly the golden age of kids’ meals.

The standard kids’ meal started with a burger (or chicken nuggets), fries, and a soda: simple and dependable. This was the era before the apple slices and milk, the “healthy” children’s options that exist today. The experience was just blissful, highly caloric, mass-produced delight, in all its saturated-fat and high-fructose glory. And the crown jewel of the kids’ meal, of course—sometimes the first course, and rarely the last—was the toy that came with the meal.

Videos by VICE

Some of the most iconic toys of the 90s—Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Tamagotchi, Disney characters—showed up on greasy trays across the country. But, perhaps the biggest frenzy arrived with a series of Pokémon collectibles from Burger King at the turn of the millennium. Pokémania hit a fever pitch in 1999, and the frenzy had a body count.

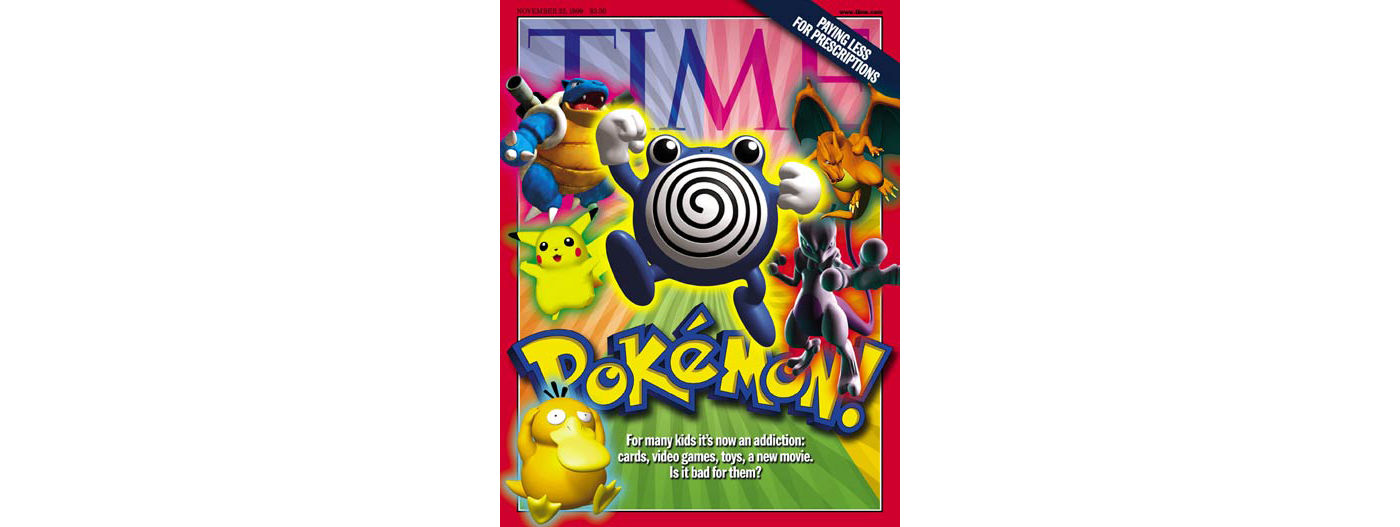

TIME magazine helped introduce the Japanese-imported phenomenon known as Pokémon to the mainstream with its November 22 cover story. At the very center of the page—a space normally occupied by heads of state, religious leaders, and business magnates—a Poliwhirl leaped out at the reader.

“For many kids it’s now an addiction: cards, video games, toys, a new movie. Is it bad for them?” TIME asked.

It felt a tad out of touch, sure, with just enough fear-mongering to lead a few parents to pause on their next trip to Toys”R”Us. Nonetheless, there was a kernel of foreshadowing in TIME‘s query.

The question of safety, at that point, was on a psychological level: How would Pokémon affect the brains, attitudes, and behaviors of children? Would a “gotta catch ’em all” obsession be totally consuming, or even damaging?

While parents, journalists, and psychologists were mulling the attitudinal implications of the fad, a far more banal Pokédanger was emerging. On December 11, 1999, 13-month-old Kira Alexis Murphy suffocated to death in Northern California. A Pokémon toy from a Burger King kids meal was believed to be the cause.

The company had begun a massive Pokémon promotion in connection with Pokémon: The First Movie, which debuted in North America on November 10 of that year, one month before Kira’s death. The 56-day promotion, one of the largest in history, was intended to run from early November to the end of December. The kids’ meal prize during that two-month period was one of 57 different Pokémon toys. Making the promotion all the more exciting was the fact that the toys were encapsulated within the immediately familiar red and white orb of a Pokéball—the fictional vessel used to catch Pokémon. Kids got to experience the three-dimensional fantasy of opening up a Pokéball to see what they’d captured. Burger King had plans to distribute over 25 million toys in this clever format for free with any kids’ meal purchase.

As far as Kira’s death was concerned, the toy itself, as it turned out, wasn’t the problem. She died after one half of the plastic Pokéball, measuring just under three inches in diameter, became attached to her face. She had somehow gotten it stuck over her nose and mouth, forming an airtight seal.

As it happened, Kira’s mother, Jill Ann Alto, took a shower for about 20 minutes. When she emerged, her daughter was dead. Kira’s two sisters, then ages four and five, witnessed the death.

“I came out and found her with the ball over her mouth and nose,” a grief-stricken Alto told the Los Angeles Times. “I had to pull it off.”

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) stepped in, urging an immediate recall of the toys and a suspension of the giveaways. But the promotion continued.

“A death should be a very grave sign that there’s a problem,” Ann Brown, who was chairwoman of the CPSC from 1994 to 2001, told the Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News in January 2000. “You don’t want to wait for a pile of dead babies before you do a recall.”

A spokesperson for Equity Marketing, the toymaker that had partnered with Burger King, would later state that the toy “meets or exceeds all federal safety guidelines.” And Charles Nicolas, a spokesman for Burger King, argued, “It was not concluded that the ball was the cause [of death].”

Ten days later, on December 23, it happened again: An 18-month-old girl in Kansas almost suffocated. By the time her father pried the half of a Pokéball from her face, the girl’s lips had turned blue. After this close call, outrage was mounting.

“When we found out about the first death, there was the realization that this could be huge national concern,” Brown, who resigned from the CPSC in 2001, tells MUNCHIES. “This was a worst case scenario: a major fast food chain, not just a toy store, distributing these toys by the millions.”

READ MORE: Burger King’s Racy Valentine’s Day Meals Come with Adult Toys

And the promotion was already proving to be a resounding success: Some Burger King restaurants were each selling 1,000 kids’ meals a day. Numerous locations were inundated with crying, screaming children—frustrated parents in tow—after selling out of all their kids’ meal supplies.

It was not a question of whether another death would occur, but when.

Regulators criticized Burger King for acting too slowly. The success of the Pokémon tie-in, it seemed, was why the chain appeared to be dragging their feet regarding a potential recall.

“[Burger King] have come around now, [but] we did have to push them,” Brown told The Washington Post in late January of 2000.

A voluntary recall by Burger King in conjunction with the CPSC began on Monday, December 28.

Brown went on NBC News’ Today show that day to discuss the recall. Her goal, she recalls, was “to make a big splash.”

The date is important. Burger King had pushed out their own press release early, on December 27, a Sunday—a move that Brown believes was intended to try and fly the announcement under the radar.

“A Sunday is not a day when there is a lot of press about something,” she tells MUNCHIES. “I was clearly not pleased with that.” The CPSC intended to do a joint press release with Burger King on December 29, allowing the organization enough time to develop a nationwide strategy.

The warnings were printed everywhere: on tray liners, on carry-out items, and on fry bags. Burger King also bought commercial time on cable and network television to inform the public, and gave out an 800-number. Unfortunately, these efforts were not enough.

“My own supposition is not factual,” Brown says, “But it’s that they didn’t want so much horrible publicity. Burger King is a family restaurant; this was certainly not publicity they were looking for.”

When the recall did go live nationwide that week, consumers were urged to immediately take the Pokéballs from children and either return or discard both halves. You’d even get a free small order of French fries for each pokéball—and kids still got to keep the Pokémon toy inside.

The recall effort was massive: In addition to Brown’s national segment on Today, notices were posted inside more than 8,100 Burger King restaurants throughout the country; an ad was placed in USA Today; notices were sent to 56,000 pediatrician’s offices and 10,000 emergency rooms, and even to websites “frequented by Pokemon [sic] fans.” The warnings were printed everywhere: on tray liners, on carry-out items, and on fry bags. Burger King also bought commercial time on cable and network television to inform the public, and gave out an 800-number. Unfortunately, these efforts were not enough.

READ MORE: A Burger King in San Francisco Is Blasting Classical Music 24/7

On Tuesday, January 25, 2000, almost a month after the recall began, four-month-old Zachary Jones was found dead in his crib in Indianapolis, Indiana. He, too, had been suffocated by a Pokéball. “It’s hard to believe that you go get the kids something to eat and you bring home a lethal toy,” Michael Jones, the boy’s grandfather, told the Chicago Tribune. His death was the last one attributed to Burger King’s Pokémon containers.

The recall was largely considered a success; even Brown later praised Burger King for their efforts. The families of Kira Alexis Murphy and Zachary Jones later settled with Burger King and toy-maker Equity Marketing for undisclosed sums. Burger King did not respond to multiple requests for comment by phone and email for this story.

In the years following, Burger King had smaller toy recalls, but nothing rivalling the scope of the Pokémon incident—and there were no deaths. And there have been indications that Burger King intends to scrap toys altogether in the future. You can now substitute the toy for a cookie, and late last year, Burger King South Africa marketing executive Ezelna Jones said that Burger King would be “moving away from toys” in an effort “to cut down on plastic by that will end up in a landfill.”

The legacy of Pokémon has been a different story. Since the most recent iteration of the game, Pokémon Go, was released in the US in July 2016, the hysteria of Pokémania has once again reared its ugly head.

More than ten people have died playing the game, once again trying to “catch ’em all.”