Punk rock might not exist if it hadn’t been for Danny Fields. Born in Queens, the legendary music magnate spent the 60s in the East Village, hanging with the likes of Andy Warhol and his superstars. He championed bands like the Velvet Underground while working as a radio host for WFMU, did publicity for the Doors and the Stooges, and by the 70s, was writing a hugely influential column for the Soho Weekly News. Fields is also the guy who discovered the Ramones.

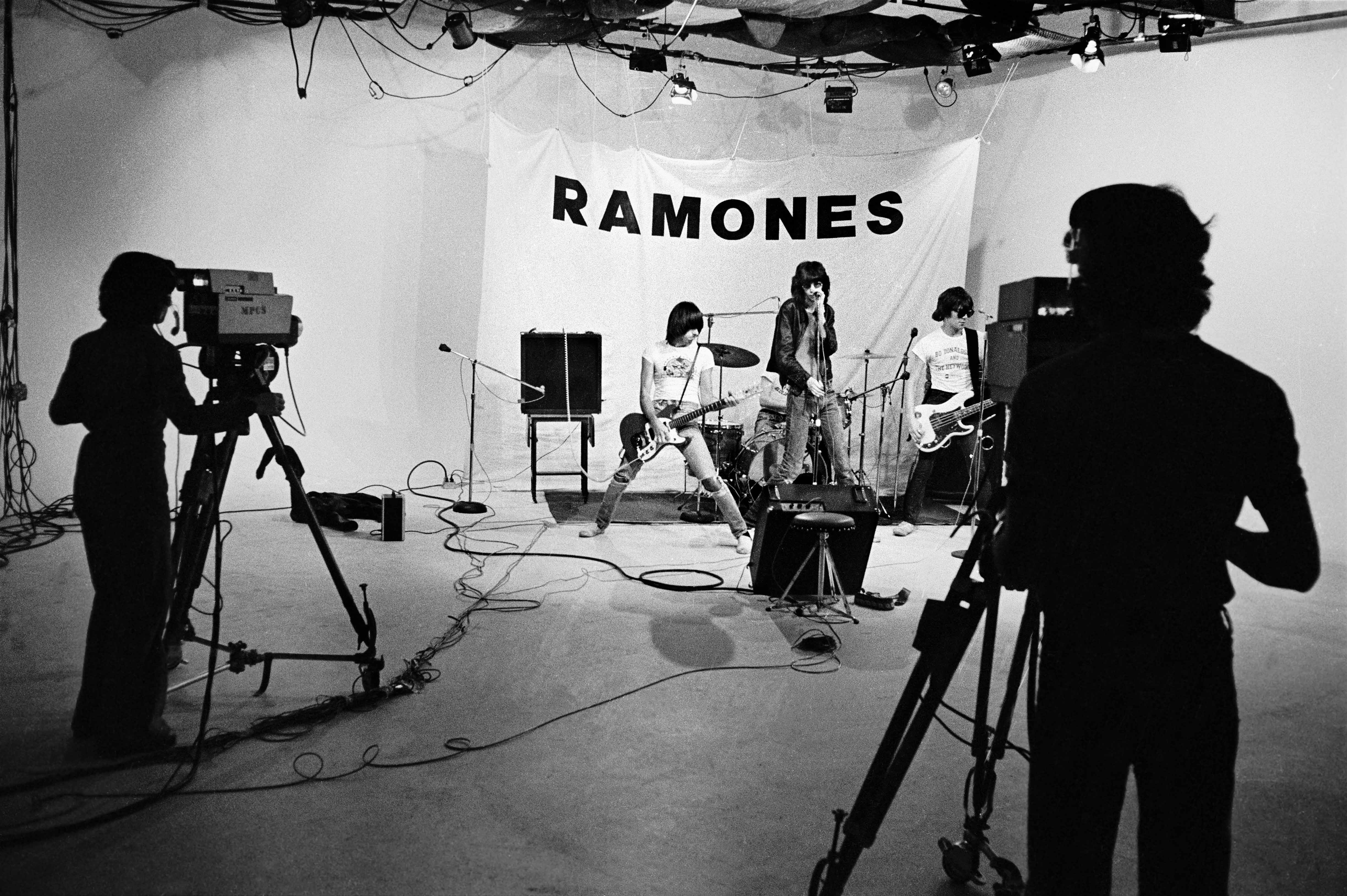

In 1975, the band begged Fields to hear them play at CBGB, and he was instantly enamored. The Ramones wanted Fields to write about them—but he did them one better and became their manager. He spent the next five years brokering record deals, arranging the band’s first video shoot, and booking their first tours, including a trip to England to play alongside the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the Damned.

Videos by VICE

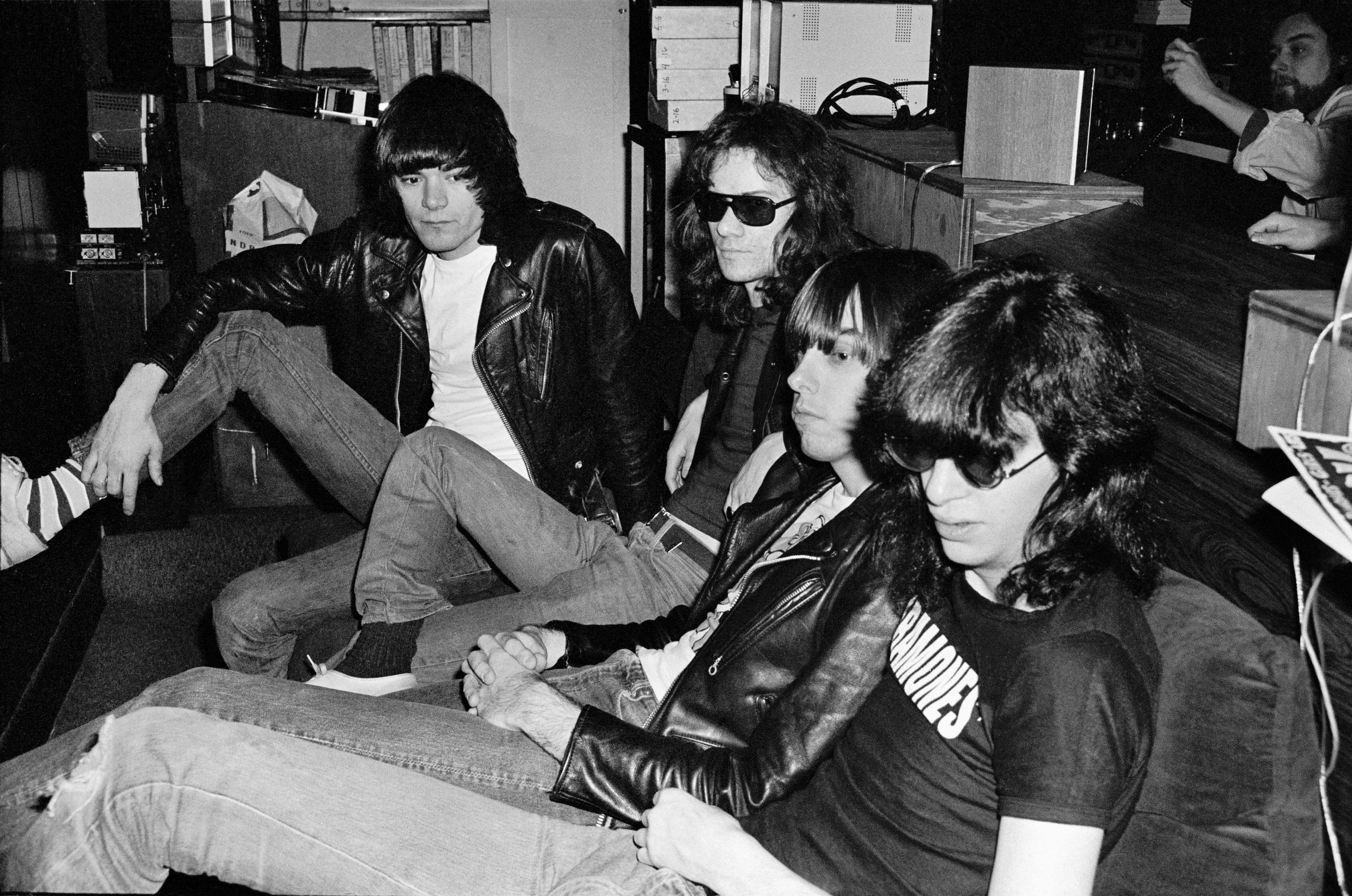

But five years in, craving superstardom, the Ramones fired Fields and hired Phil Spector, the manager who notoriously pointed a gun at Johnny Ramone and demanded he play a riff repeatedly. But during his brief tenure, Fields meticulously documented the band’s rise, amassing an incredible archive of photos from the band’s early days. In 2016, Fields released a collection of them as a rare limited edition photo book. But now, My Ramones (Reel Art Press) is being republished and getting a wide release.

VICE tracked Fields down recently to chat about what it was like managing the Ramones in their wildest years.

VICE: Could you describe the scene at CBGB back in 1975?

Fields: There was a confluence of melodic and lyrical talent and a wanting to be different. You were inspired to take it further and New York was a good place to do it. CBGB was on the ground floor underneath a flophouse on the Bowery. It was a long, dark, narrow bar that had recently become available to people in our crowd [who used to hang out] in the back room of Max’s Kansas City.

The great heroes of New York are the people who invented a place where people went. Hilly Kramer, the owner of CBGB, had been a songwriter and country singer who made records. He had an ear and eye for music. CBGB had incredible acoustics. You felt like you were sitting inside of a guitar.

Johnny Ramone was not let into Max’s once and he never forgave them. That was the beginning of the class warfare, and you see the rise of a ferocious working class product that’s insane and brilliant. Would I say that about them then? No. If you asked me then to describe it, I would have said it was rock n’ roll. The Ramones were making mischief by laying an attitude that was excellent.

How did you first connect with the Ramones?

I went to see them at CBGB because Tommy Ramone begged me; they wanted me to mention them in my weekly column in the Soho Weekly News. They were insistent and I didn’t mind because I respected people who didn’t back down and kept at it.

I told Tommy I was coming. I said hello to them before the show and told them I would meet them afterwards in front. They played and I was like, “Wow, this band is perfect. This is great. I love it. Louder! Louder! Faster! Faster!”

When you listen to the first album now it sounds quaint especially compared to their last live albums. They were a fluke quartet—but they were beginning with an awareness of presentation. They worked it all out. They all took the same last name. The two people with guitars had the same haircuts. They were impeccably dressed in the same outfit that was to become their uniform. They were individuals but there was a groupness to them that was perfect.

So back to the narrative: 12 minutes later, after they had done 17 songs, we met as planned on the sidewalk in front of the club. They asked, “So, did you like us?” They were very forward. I said that I liked them very much. They asked me if I would write about them and I said, ”Yes, I’ll write about you, and what’s more, I want to manage you.”

Johnny said, “We need three thousand dollars for drums.” (Laughs). The assumption was I was advancing them the money, and it wasn’t that big a deal. So I went to Florida and asked my mother for the money. She wrote a check and said, “I hope you know what you are doing.”

Could you give us insight into the individual personalities of each of the original members?

Johnny wanted to break out of being a bricklayer, married young, and—as he says in his autobiography—being the kind of person who would throw a brick through a window while walking down the street. And then one day he stopped and decided to make a life, be good, be famous, and not hurt strangers anymore.

Joey was the quiet one who never talked. He didn’t want to sing back then. He was the geek of the universe he was in. For him to stand up in front of people and do what he did was incredibly brave. I was in awe of his sense of humor and his ability to mock, to deride, and to dismiss. With a chortle, he would send people to the guillotine. He made me nervous.

Dee Dee was the most social. He lived with me and wanted to meet other musicians in other bands—and none of the others cared about that. They just wanted to meet girls, but Dee Dee wanted to be out there and be a rockstar.

Tommy was the shyest, most literate, and most aware of what was happening in art, movies, and the avant-garde. It was Tommy’s band in the beginning—he and Johnny took care of the music, and he and Arturo Vega did the visuals. Tommy didn’t like having to perform in front of an audience and preferred a quieter life that was created in a different way. He left in ‘78.

Can you talk about some of the tensions in the group?

They were never on really good terms—they all hated each other. They were different and they fought. They did it pretty openly, except not in front of strangers. After the show, they would lock themselves in their dressing room. I would have to stand at the door because the VIPs were coming and say, “They’re just drying off.”

They would be inside and you could hear Johnny punching Dee Dee and slamming him across the room because he missed the opening by a 64th of a second or something. He would be yelling. Then they’d have a beer, and someone would open the door to tell me, “OK, they can come in now.” They’d be sitting there just perfect. The blood had dried [Laughs] and they were ready to meet people.

More important than that were the fans who would wait at the stage door—Johnny knew those were the most important fans who were going to bring other kids along with them. He would give strict orders not to start the engine until we had spoken to every person who was trying to get an autograph.

Why did you leave?

They fired me. They hadn’t sold any records. They all believed that their songs were so good that they would sell millions of records in the first six months and then by the end of three years, they would be so rich that they could retire for life, which started to look very impractical early on. But I was only there for the first five years.

I am sorry I missed commissioning when they were selling out stadiums of 80,000 people as well, come to think of it. In Argentina, police would cordon off the neighborhood where they were staying because they were so big. I never got to see that. I only reconnected with them when Joey died.

How would you describe their legacy?

They had stopped playing, but they were Ramones until they died. They were inspirational to other bands just as the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, and the New York Dolls were to them. The Dolls couldn’t play and that was inspiring to know—you didn’t have to be Eric Clapton or Eddie Van Halen. You could bang it, down stroke it, and make a new noise that you wanted to hear.

They never had a hit. Their first album took 38 years to go gold. If you compare their dreams of retiring in three years, it was so different from that. But I have got to hand it to them. Years later, they got extremely rich from their TV commercials: “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go!” It’s melodic, and driven, and fast. It’s an anthem and people don’t even know who it’s from.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Miss Rosen on Instagram.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: HoYoverse -

Eva Pascoe, founder of Cyberia, poses at the cyber cafe in London. All photos courtesy of Eva Pascoe, Ali Knapp, and Roger Green. -

(Photo by Niels van Iperen/Getty Images) -