Mickalene Thomas’s vivid paintings, collages, and photographs boom off the wall—they confront the viewer head on, their subjects as bold and assertive as their style. Over the course of her prolific career, Thomas has created a body of work that expands notions of beauty, gender, and race and offers a complex, celebratory vision of what it means to be a woman—and particularly a black woman—today. The artist’s commitment to complexity is reflected in all aspects of her practice, which encompasses photography, video, collage, and painting. Thomas brings a feast of references to the table, breezing between pop culture and the long lineages of both Western and African art. The artist restages fraught historical tropes like the odalisque—the classic depiction of a nude woman reclining in an exotic setting—in terms that empower rather than objectify her subjects, transforming the passivity of the pose into a positive performance of femininity.

Both the roles her subjects lay and the interiors or landscapes they inhabit are highly constructed. Women strike bold poses and face the viewer head on, surrounded by decorative patterns inspired by Thomas’s childhood growing up in the 70s and 80s in New Jersey. Thomas takes pleasure in seductive materials—rhinestones, enamel, and textile prints—but strikes a careful balance between celebrating beauty as something sensual and addressing it as a set of ideals that can be harmful to those who don’t conform to them. It’s this ability to contain contradictions—to wrestle stereotypes, history, and the demands of the culture industry into loud but harmonious images—that makes her one of the most important artists working today.

Videos by VICE

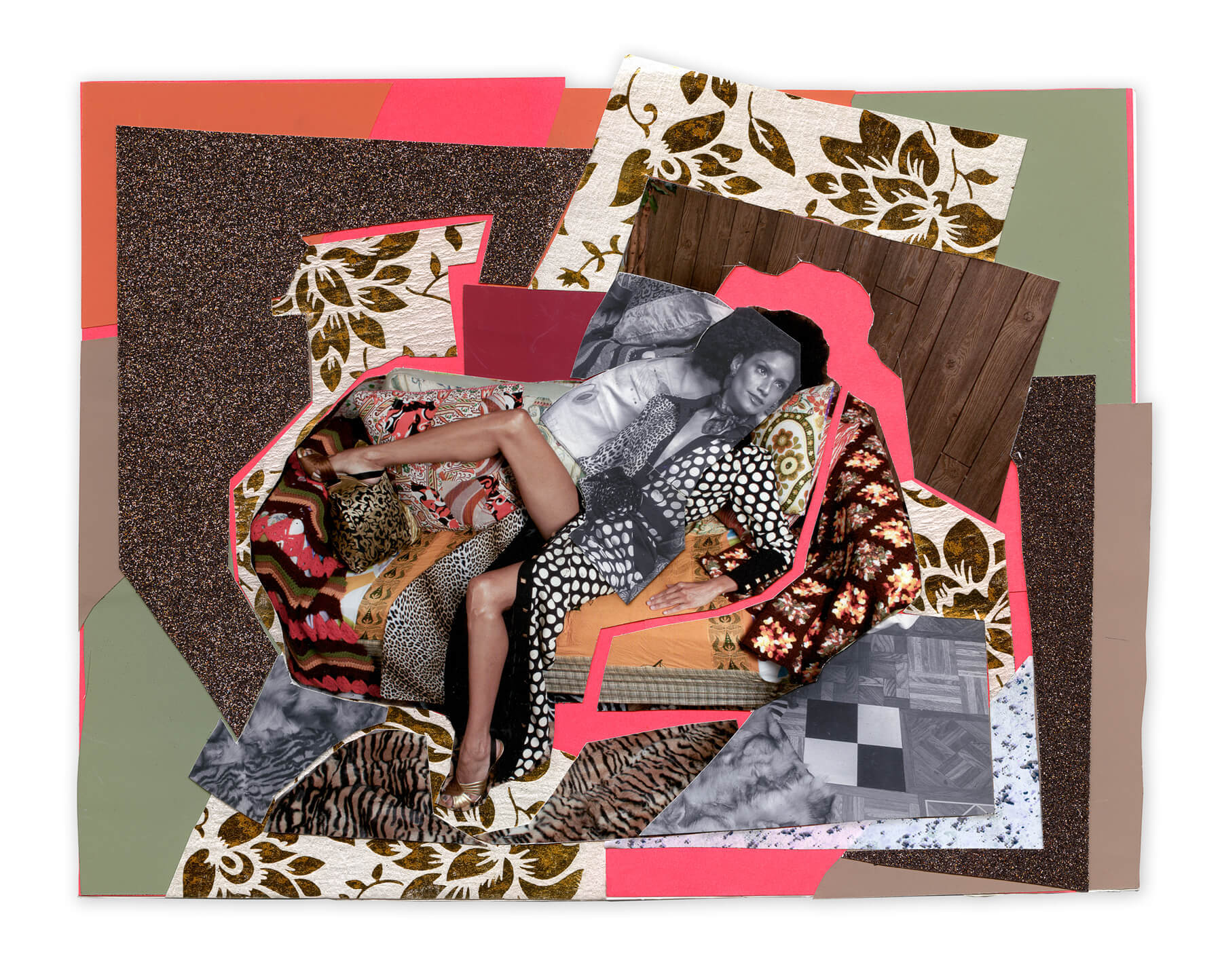

“Racquel Is All I Need,” 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

BROADLY: Tell me about growing up, your education. What brought you to art?

Mickalene Thomas: I came to art relatively late, as a young adult, when I was living in Portland, Oregon, in the early 90s. I had moved there to go to school, majoring in pre-law with a minor in theater arts, but hanging out with a lot of artists and musicians there who were doing great things, I was inspired to make work of my own. Gradually, I became more interested in developing my own practice and started my career by attending Pratt Institute for my BFA. Then I received my MFA from Yale University.

Read more: Meet the Artist Making GIFs to Ridicule All the Shit Women Deal With

You painted the first individual portrait of a First Lady, and the first non-white First Lady: Michelle Obama. Did she sit for you, or did you work from photographs? What was that like?

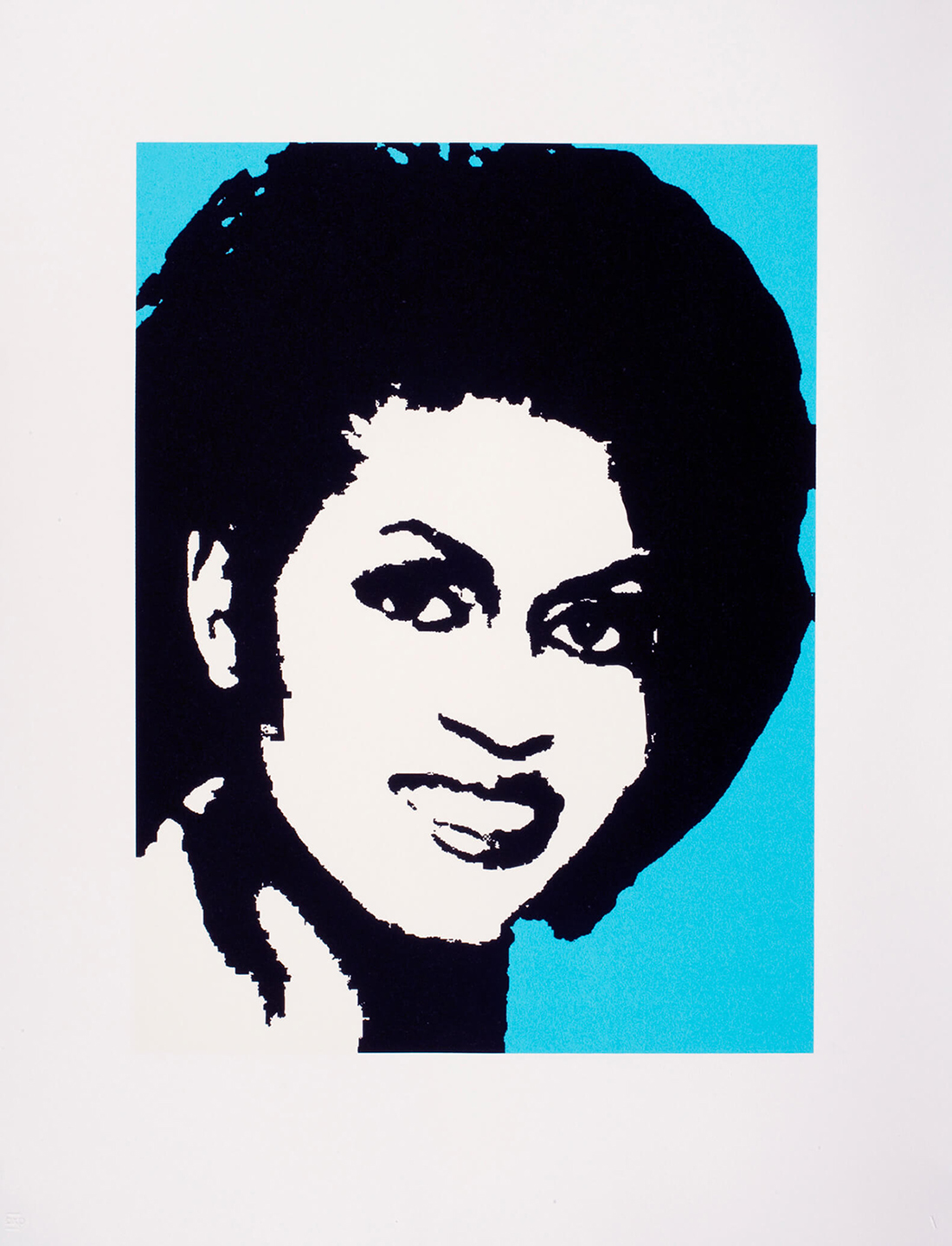

When I was first approached to work on the portrait of Michelle Obama, it was at the height of Obama’s inauguration, and I could already see that Michelle was quickly becoming a major figure of both and power. I started to think of her as the Jackie O of our generation, and began pulling images from my research with Andy Warhol’s portrait of Jackie Onassis in mind. I wanted to recreate this iconic portrait that could serve as a symbol of the time, and as a great reminder for people of the excitement that was happening around Obama’s inauguration as the first African-American President. It was such a powerful moment in our history, bringing people together for change and awareness, and I’m so proud to have taken part in the celebration.

“Michelle O,” 2008. Courtesy of the artist, Brand X Projects, and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

How did you determine the for the portrait?

Looking again at Andy Warhol’s silkscreen portraits, I knew I wanted to create my image of Michelle Obama in the same fashion. Warhol’s use of images portrays notable, iconic people that reflect their times. It was important for me to use a technique that immediately represents pop culture.

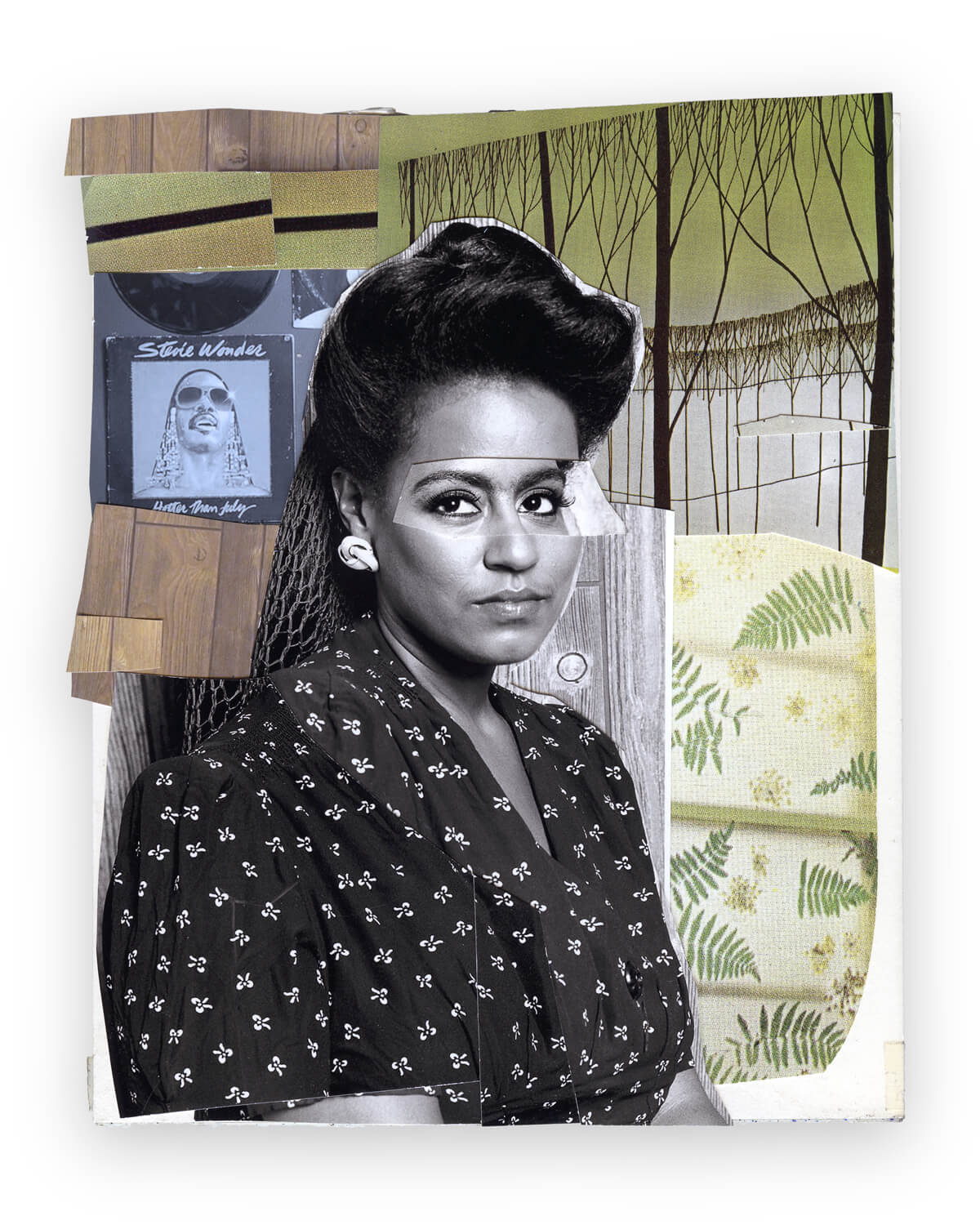

Let’s talk about your Muses works. There’s a balance in your photographs and paintings between acknowledging the theater around the whole thing—these women as characters—and acknowledging them as real individuals. It feels like a very joyful performance of femininity. What’s your relationship to these subjects, and how do you want them to work?

When I first started using photography as a tool, I was mostly shooting self-portraits, through which I learned that a pose” is essentially a performance. It’s a conscientious, affected way of presenting oneself and fulfilling a role. So when I began to work with other women, who were mostly my friends, family members, and lovers, using my tableaux as backdrops for their portraits, I wanted them to engage with the space, just as an actress would entering a theatrical stage.

Recently I’ve collaborated with women who I’ve met through friends as well as casted women from agencies. I continue to relinquish some control to my models with the intention of allowing them to own the space. I want their genuine individuality to manifest and permeate these constructed settings, while simultaneously insisting on their presence with their directness and gaze.

“Sandra: She’s a Beauty,” 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

You work across media: photography, collage, painting, video. Tell me about your studio practice. How does a painting begin for you?

My photographs and collages usually serve as a starting point for my paintings. There are certain spontaneous elements I cannot achieve in a painting that I know I can convey through these mediums. Paintings don’t necessarily have anything to do with the real image itself, but can depart from it to become my fantasy.

Starting with my photographs, I make collages and then develop the image of the model in different, cacophonous spaces. The interiors and landscapes of my collages are highly constructed representations of a particular view of the world. The women in my work play roles that are just as highly constructed, and I really enjoy the psychological intensity between these figures, their gazes, and the spaces they inhabit.

I’m interested in the various layers of presentation, perception, and masking that influence of how we see a person. Certain objects, patterns, colors, and spatial relationships bring to mind such diversified ideas of beauty, time, and nostalgia; that’s ultimately what I want to achieve through my work.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

The 70s are a big aesthetic touchstone for you. You were born in ’71, so you were very young then. Why is that era so present for you?

I’m mostly trying to reference my childhood, and the environment that I found to be most inspiring as a young girl. I don’t necessarily think of it as being representative of a specific cultural or ethnic identity—while that may serve as one of the inspirations, it really is meant to reflect on the extensions of my own identity and history. I suppose they partly reflect my nostalgia for how I lived, where my family used to gather to sit and talk.

Video still, “Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman,” 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Your film Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman presents a conversation with your mother about her dreams as a young woman and her history with drugs and illness, and it ends with her becoming one of your models. Did the impulse to make the film come out of her sitting and posing for you?

The impulse came out of my curiosity of wanting to learn about my mother as a person, to separate that from my relationship as her daughter—to really look at her as the human being she was. The film focused on my mother’s story in particular, but throughout my work, through portraying real people, people that I personally know, I’ve found that there are such complex layers to everyone’s narratives. I see the documentary as a celebration of my mother and her journey, but I also want the film to serve as a reminder that there are complexities in everyone’s stories, and not just hers.

You’re very playful with the dialogue between African and Western traditions in the history of painting. What’s your relationship to that history? Are you viewing it as a tool, or something that needs to be redressed?

I draw a lot of inspiration from the canonized images in the history of art, and part of that drive comes from a desire to claim these celebrated images of beauty and reinterpret them in my own way. I’m inserting the figures of black women, who have largely been forgotten or marginalized throughout the history of Western art. I am creating the context I want my work to be viewed within; rather than my work being considered as a commentary or even a departure, I actually want to take some ownership of or participate in the conversation when we talk about Matisse, Manet, Romare Bearden, Balthus, Courbet, or even Warhol and Duchamp.

“Portrait of Din #4,” 2012. Courtesy of the artist, Kai Gupta Gallery, Chicago, and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As a black female artist with black female subjects, your work is often framed by identity politics. What’s your relationship to these discourses?

The fact that I am a woman artist inherently shifts the classic discussion of the male gaze. As a woman, I find myself identifying with my models, and I’m not at all interested in reducing them solely to the objects of my work. While the women in my work celebrate different notions of beauty, I think simultaneously they are providing a confrontational barrier that challenges the clichés traditionally laid on women of color. Through their assertive gazes, they are demanding to be seen, to be heard, and to be acknowledged.

You use very seductive materials—rhinestones, great patterns and fabrics. It’s clear that these aren’t just “decorative” choices; how do the materials function conceptually in the work?

I started playing around with rhinestones when I became interested in notions of pointillism during my undergrad years. In relation to my work, rhinestones seemed to be the most relevant material; they provide a perfect combination of content, process, and material. As a “decorative” material, they serve to challenge our ideas of what a paintings is, and can be. There was also a great satisfaction in the slow, meditative process of gluing each and every rhinestone to the surface of the painting.

Most of the fabrics I use are chosen with the intention of reconstructing elements of my childhood. My grandmother used to reupholster a lot of furniture; I always found that to be fascinating when I was growing up. Formally, I use them to complicate and break up the picture plane, just as I do with my photographs in my collages.

Both of these elements, alongside other materials that I employ, represent the notion of artifice, constructed ideas, and how we consider adornment of ourselves and of our environments: the concept of dressing up or covering something up. How we can utilize and manipulate them to exude a certain quality, beauty or light.

“Naomi Looking Forward #2,” 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

That’s a good place to talk about how you approach beauty. Your work indulges in beauty as something sensual and positive, and also addresses it as a set of cultural ideals that can be damaging to subjects who don’t identify with them.

I think beauty and ugliness are entwined propositions. When I used to collaborate with my mother, I witnessed her projecting and embodying a very powerful sense of her own beauty, yet her faith in her glamour and her femininity was a fragile, vulnerable thing. This combination of overwhelming beauty and vulnerability is where I found the heart of my mother’s charisma; I try to express some of this complexity in my paintings.

When I consider notions of beauty, I think of Lacan’s theories in relation to validation. The notions that he puts forth are interesting to me—he speaks of the representation of the mirror and how we see ourselves. But we don’t see ourselves or know our own beauty until it’s validated by how others see us. The mirror as an object is powerful because it’s the only time we see our own reflection. But the validation from others gives us true meaning.

“Clarivel with Black Blouse and White Ribbon,” 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mickalene Thomas’s new show “Mickalene Thomas: Do I Look Like a Lady?” opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, on October 16, 2016 and runs through February 6, 2017. Lede image credit: Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires 2010. Courtesy of the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

More

From VICE

-

A gang of men hide in a clown car at the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus. April 1977, New York City. -

-

Marilyn, an attorney and former professional dominatrix, poses for a photo with her sub who is fully encased in latex on the Vancouver Fetish Cruise. Photo by Paige Taylor White. -