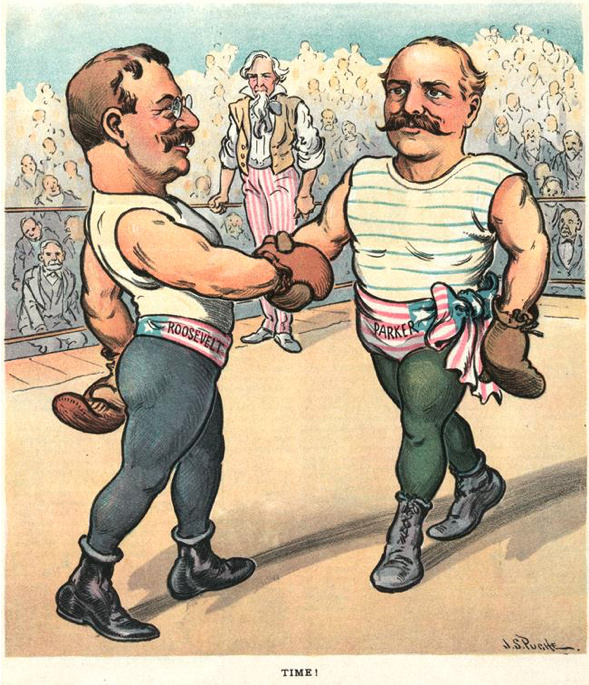

“I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph,” Theodore Roosevelt, then Governor of New York, declared in his 1899 speech “The Strenuous Life.” “We admire the man who embodies victorious effort; the man who never wrongs his neighbor, who is prompt to help a friend, but who has those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life. It is hard to fail, but it is worse never to have tried to succeed. In this life we get nothing save by effort. Freedom from effort in the present merely means that there has been stored up effort in the past.”

The future 26th President of the United States of America was speaking both figuratively and literally here. “The Strenuous Life” was a strident argument in favor of bootstrap-pulling, nationalism, and masculinity, among other things. But Roosevelt was also in favor of hard work that tested and strengthened the body as well as the mind, the soul, and the nation. His own life had been influenced and improved by a significant number of strenuous pursuits. Sometimes described as a “locomotive in human pants“, he almost turned tennis into a combat sport at one point. He augmented his ostensibly moderate hikes with various obstacles until they’d morphed into proto-Tough Mudder-style challenges. He also trained extensively in multiple martial arts, a good century or so before that became the thing to do.

Videos by VICE

As a child, Roosevelt first turned to boxing as a means of self defense. He was asthmatic and weak, and easy prey for a number of bullies. “Having been a sickly boy, with no natural bodily prowess and having lived much at home, I was at first quite unable to hold my own when thrown into contact with other boys of rougher antecedents,” he wrote in The Autobiography of Theodore Roosevelt. “I was nervous and timid.”

After a particularly demoralizing beatdown on a trip to Moosehehead Lake, a fourteen-year-old Roosevelt asked his father for boxing lessons and received his hearty approval.

He was a late bloomer. “I was a painfully slow and awkward pupil, and certainly worked two or three years before I made any perceptible improvement whatever,” he writes in his autobiography.

But his lessons were not without their moments of triumph. “My first boxing-master was John Long, an ex-prize-fighter. I can see his rooms now, with colored pictures of the fights between Tom Hyer and Yaknee Sullivan, and Heenan and Sayers, and other great events in the annals of the squared circle. On one occasion, to excite interest among his patrons, he held a series of “championship” matches for the different weights, the prizes being, at least in my own class, pewter mugs of a value, I should suppose, approximating fifty cents. Neither he nor I had any idea that I could do anything, but I was entered in the lightweight contest, in which it happened that I was pitted in succession against a couple of reedy striplings who were even worse than I was. Equally to their surprise and to my own, and to John Long’s, I won, and the pewter mug became one of my most prized possessions.”

Roosevelt went on to compete in both boxing and wrestling while he was at Harvard, with somewhat less impressive—but arguably no less exciting—results.

In a 1957 article for the The Harvard Crimson about Roosevelt’s time at the storied institution, Philip M. Boffey touches on the politician’s competitive history: “Roosevelt did not participate on any college teams, but he gained local fame for his boxing exploits. He entered several college boxing tournaments, and though only modestly successful, his obvious courage and determination won him a small following.”

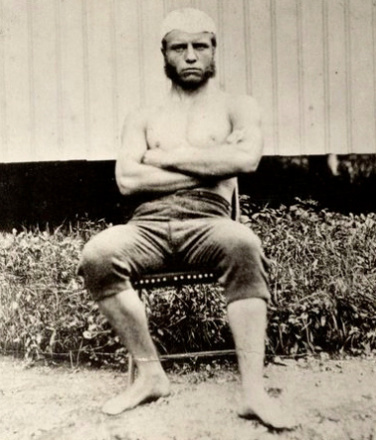

Teddy Roosevelt as a young man.

Apparently he fared better outside of competition. “Sometimes Roosevelt’s fighting was impromptu,” Boffey writes. “Frederic Almy, his class secretary, recalls that during a torchlight procession in the Hayes-Tilden presidential campaign a bystander on the sidewalk said something derogatory. The impulsive Teddy thereupon, recording to Almy, ‘reached out and laid the mucker flat.’”

Boffey then goes on to share a pair of anecdotes from a lightweight tournament held at the Harvard gym in March of 1879: “He won his first match, and also won the crowd with one of those chivalrous acts which sporting fans love. When the referee called “Time,” Roosevelt immediately dropped his hands, but the other man dealt him a savage blow in the face. The spectators shouted “Foul, foul!” and hissed, but Roosevelt is supposed to have cried out “Hush! He didn’t hear.”

“In his second match, he met Charley Hanks. They both weighed about 135 pounds, but Hanks was two or three inches taller and had a much longer reach. Roosevelt was also nearsighted, which made it hard for him to see and parry Hanks’ blows. “When time was called after the last round,” one spectator recalls, “his face was dashed with blood and he was much winded; but his spirit did not flag, and if there had been another round, he would have gone into it with undiminished determination.”

“From this contest sprang the legend that Roosevelt boxed with his eyeglasses lashed to his head, but some thirty years later T.R. said, “People who believe that must think me utterly crazy; for one of Charley Hanks’ blows would have smashed my eyeglasses and probably blinded me for life.”

For the majority of his political career as the Governor of New York (1899-1900), 25th Vice President of the United States (1901) and 26th President of the United States (1901-1909), Roosevelt favored grappling. As Governor, he hired the then American middleweight wrestling champion, who was also in Albany at the time, to train him three or four times a week.

“Roosevelt, who was in his early 40s at the time (nearly double the age of the wrestler), looked forward to his training sessions so much that he eventually bought a wrestling mat for the workout room,” Jon Finkel writes in Teddy: Roosevelt: The U.S. President That Was Always Tough And Ready To Throw Down for The Post Game. “While neither combatant had a problem with the wrestling mat, Roosevelt’s Comptroller did, and he refused to audit the bill for the mat, claiming that wrestling wasn’t ‘proper Gubernatorial amusement.’”

The Comptroller suggested a billiards table, but Roosevelt wasn’t interested and continued sparring with the champ and whoever else would take him on. After one particularly brutal battle in which Roosevelt managed to rough up both his opponent (a friend of the wrestler’s who was a rower by trade) and himself, the Governor decided that it would be best if he stopped boxing for the rest of his term.

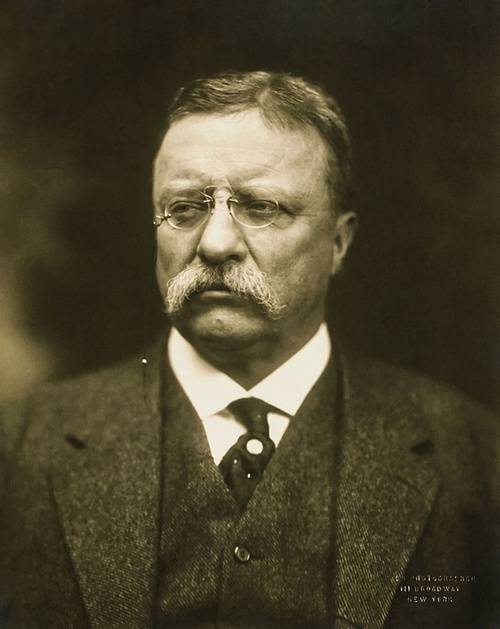

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Once he was in the White House, though, Roosevelt was back to doing whatever he wanted athletically, proving that wrestling, boxing, and judo were all proper Presidential amusement. “Roosevelt wasn’t exactly shy about his hobby,” Jenny Drapkin write in Theodore Roosevelt: Mojo in the Dojo for Mental Floss. He lined the White House basement with training mats, and he practiced with anyone who was willing to tussle—including his wife and sister-in-law. Once, he even brightened a boring state luncheon by throwing the Swiss minister to the floor and demonstrating a judo hold, to the delight of his guests.”

“He voluntarily subjected himself to a staggering number of brutal sparring sessions with championship-caliber fighters,” writes Finkel. “Boxers; wrestlers; martial artists—it didn’t matter to Roosevelt. If they’d be willing to punch him in the face or pin him to the ground, he’d take them on. He felt it was the only way he could maintain his ‘natural body prowess.’”

In a further effort to maintain said natural body prowess (and to control his weight, which was expanding in the early twentieth century), Roosevelt took judo lessons from Japanese master Yoshiaki (Yoshitsugu) Yamashita. He’d acquired a taste for the sport when a wrestling instructor taught him a few moves he’d picked up while working in Japan and was eager to learn more. Roosevelt then practiced those moves on every willing participating/victim he could find.

“The President’s training partners included his sons, his private secretary, the Japanese naval attache, Secretary of War William Howard Taft, and Secretary of the Interior Gifford Pinchot. When these people were unavailable, then Roosevelt tried tricks on husky young visitors,” Joseph R. Svinth writes in Professor Yamashita Goes to Washington, a 2000 article for the Journal of Combative Sport.

In a 1923 article in The Outlook, one of those visitors, Robert Johnstone Mooney, recounted the sparring session that he and his amateur boxer brother had with the President: “[He] sprang to his feet and excitedly asked: ‘By the way, do you boys understand jiu-jitsu?’ We replied in the negative, and he continued, pounding the air with his arms, ‘You must promise me to learn that without delay. You are so good in other athletics that you must add jiu-jitsu to your other accomplishments. Every American athlete ought to understand the Japanese system thoroughly. You know’—and he smiled reminiscently—’I practically introduced it to the Americans. I had a young Japanese—now at Harvard [A. Kitagaki]—here for six months, and I tried jiu-jitsu with him day after day. But he always defeated me. It was not easy to learn. However, one day I got him—I got him—good and plenty! I threw him clear over my head on his belly, and I had it. I had it.’”

An overabundance of enthusiasm was a common problem for Roosevelt. “According to an American journalist named Joseph Clarke, Yamashita later said that while Roosevelt was his best pupil, he was also ‘very heavy and very impetuous, and it had cost the poor professor many bruisings, much worry, and infinite pains during Theodore’s rushes to avoid laming the President of the United States,’” Svinth recounts.

Yamashita’s efforts to save the President from himself payed off. Roosevelt became America’s first brown belt while in office and remained the most decorated politician in martial arts until Russian President Vladimir Putin earned his eight degree black belt in karate. He continued happily sparring in his own unique mix of martial arts right up until his trademark enthusiasm earned him a devastating boxing injury in the middle of his presidency.

“Once again, TR found himself in the squared circle with a man almost half his age. After holding his own for several rounds, the president missed landing a left hook on his opponent, and the young captain ‘cross countered [the president] on the eye, smashing the little blood vessels,’” Finkel wrote. “Roosevelt’s eye never healed properly, which meant the punch signaled the end of our most storied presidential pugilist’s career.”