In just a few taps and clicks, the tool showed where a car had been seen throughout the U.S. A private investigator source had access to a powerful system used by their industry, repossession agents, and insurance companies. Armed with just a car’s plate number, the tool—fed by a network of private cameras spread across the country—provides users a list of all the times that car has been spotted. I gave the private investigator, who offered to demonstrate the capability, a plate of someone who consented to be tracked.

It was a match.

Videos by VICE

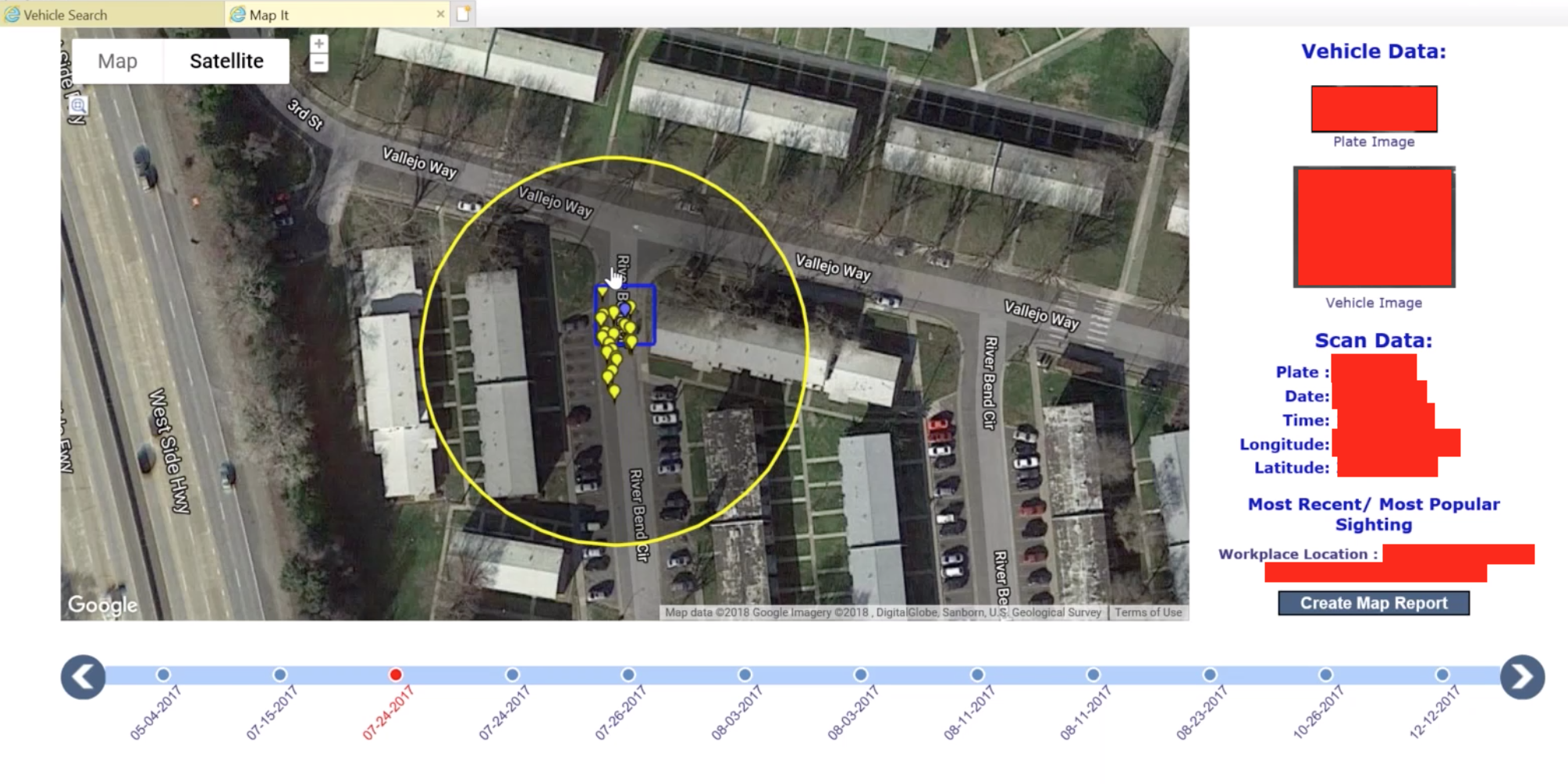

The results popped up: dozens of sightings, spanning years. The system could see photos of the car parked outside the owner’s house; the car in another state as its driver went to visit family; and the car parked in other spots in the owner’s city. Each was tagged with the time and GPS coordinates of the car. Some showed the car’s location as recently as a few weeks before. In addition to photos of the vehicle itself, the tool displayed the car’s accurate location on an easy to understand, Google Maps-style interface.

This tool, called Digital Recognition Network (DRN), is not run by a government, although law enforcement can also access it. Instead, DRN is a private surveillance system crowdsourced by hundreds of repo men who have installed cameras that passively scan, capture, and upload the license plates of every car they drive by to DRN’s database. DRN stretches coast to coast and is available to private individuals and companies focused on tracking and locating people or vehicles. The tool is made by a company that is also called Digital Recognition Network.

What DRN has built is a nationwide, persistent surveillance database that can potentially track the movements of car owners over long periods of time. In doing so, highly sensitive information about car owners can be made available to anyone who has access to the tool.

Even if you’re not suspected of a crime or behind on your car payments, your location information may be included in this database—in fact, the vast majority of vehicles captured are connected to innocent people. DRN claims to have more than 9 billion license plate scans, according to a DRN contract obtained by Motherboard. And DRN has admitted that people who are not supposed to be allowed to use the tool have gained access.

“DRN provides a very powerful tool to private industries such as insurance, investigations and asset recovery. A powerful tool can be abused and such abuses would infringe on the privacy of Americans,” Igor Ostrovskiy, a New York based private investigator with a firm called Ostro Intelligence, told Motherboard.

In Motherboard’s test, we found a person who consented to have their license plate entered into the DRN system. They then verified that the photos were of their car, and provided context of where the photos had been taken.

“Looks like that’s in front of my house!” the person said. The photo also included part of the building the car was parked in front of. Motherboard granted the person anonymity to protect their privacy. “Creepy,” they added.

Motherboard also obtained the results of a DRN search of a vehicle that was located primarily in a large U.S. city. These results were even more granular, showing their movements across the city on the highway, on smaller streets, and spotted in specific neighborhoods, too.

The data is easy to query, according to a DRN training video obtained by Motherboard. The system adds a “tag” to each result, categorising what sort of location the vehicle was likely spotted at, such as “workplace” or “home.”

Do you work at DRN or Vigilant? Did you used to? Or do you have more information about license plate readers? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

“If the scans are happening during the day, it’s assumed that the vehicle is at a work location,” a narrator says in the training video while demonstrating the tool. “If they were, say, in the evening, 6 p.m. to, say, 6 a.m., then this would show up as a residential location. It’s assumed that the person’s home.”

The table of results shows the most recent or popular sighting at the top, and clicking an option called “Map It” at the top of the tool’s control panel plots the location data onto a map for easier viewing. Users can create a PDF of their search results, which includes the map with all of the selected results, as well as the addresses of where the vehicle was spotted each time.

DRN charges $20 to look up a license plate, or $70 for a “live alert”, according to the contract. With a live alert, a user can enter a license plate they wish to receive updates on; when the DRN system spots the vehicle, it’ll send an email to the user with the newly discovered location.

“DRN takes data security seriously,” DRN told Motherboard in a statement. “It is a violation of the terms of our contract for a user to access or use the data for non-business purposes, or to provide access to a third-party—including media and reporters—in any form for any reason without DRN’s approval. Customers are also responsible for adhering to the terms of the contract to manage and monitor their users for appropriate system use and access privileges. Additionally, customers have specific obligations to comply with all laws, regulations and rules that govern the use of the data within DRN’s solutions.”

***

Over the last decade, DRN has created its license plate and photo database by outsourcing the collection process to its own customers. As repo men drive around the country in unmarked cars, they have a set of DRN cameras installed on their vehicle, scanning the plate of every car it sees. A four camera kit costs $15,000, according to DRN’s website. This tech not only alerts the driver if they pass a vehicle that has been marked for repossession by querying DRN’s database, but also constantly photographs any cars it passes and adds those photos to the database itself. DRN has more than 600 of these “affiliates” collecting data, according to the contract. These affiliates are paid a monthly bonus for gathering the data.

“DRN Affiliates equipped with LPR cameras scan license plates every day, building up a historical scan database that serves the Affiliate and the entire network in generating more hits and recoveries. DRN maintains the largest database of scans and the numbers continue to grow daily,” DRN’s website reads.

In marketing materials, DRN says it is “a game changer for insurance carriers” who can use the technology to catch people insuring their vehicle in one state for a cheaper price while actually living elsewhere. Meanwhile, DRN’s contract says the company has helped recover over one million vehicles since 2009 and saved billions of dollars for commercial clients. While DRN is focused on providing license plate reader technology to private industries, its sister company Vigilant Solutions sells the same technology to government agencies such as law enforcement. Vigilant also sells facial recognition products.

As well as providing its customers with access to its data banks of car location data and photos, DRN also resells that access to other companies who cater to even more clients. Those include a company called Delvepoint which more explicitly markets to private investigators.

“Theoretically with law enforcement, police go through training,” on how to properly use this technology in line with the law, Dave Maass, senior investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), told Motherboard in a phone call. “None of that affects private use.” Taking photos in public is generally protected by the First Amendment, and so many of the photos in the database are likely to have been taken legally.

There is wide room for abuse though. Maass pointed out that could include stalking, obtaining information for litigation through undisclosed means, gathering information on celebrities to sell, or more.

“Looks like that’s in front of my house!”

Over 1,000 accounts have access to the DRN system, the contract adds. These accounts can be shared among multiple people at an organization, though. In a closed Facebook group for private investigators that Motherboard gained access to, multiple posts include people asking for others to run plates for them through their own access to a license plate reader system, though they did not specifically mention DRN.

Company executives have previously admitted unauthorized users have gained access to the system. In a hearing in the City of Kyle, Texas, Vigilant Solutions Vice President of Sales Joseph Harzewski told councilmembers “we’ve had people hand out access where they shouldn’t have.” Harzewski added that this data exposure is “something we can’t do anything about, in the sense that we give bulletproof technology to our clients. They’re free to do with it as they see fit. We give them the complete control to ensure that what they decide to do with it is what happens with it.”

Notably, DRN does not immediately ban someone for abusing the service, according to the contract. It reads that if DRN determines or suspects that the user has used the data for personal or non-business purposes, “Licensor [DRN] shall notify Licensee in writing of the alleged breach and give Licensee an opportunity to cure any curable breaches within 30 days of Licensee’s receipt of such notice; thereafter Licensor may take immediate action, including, without limitation, terminating the delivery of, and the license to use, the Licensed Data.”

And members of the public have no realistic way of knowing whether their data has been collected by DRN, or examined by a DRN user. There are very few ways to pry information from private companies; details about government surveillance networks are at least theoretically subject to Freedom of Information Act requests and government oversight.

“Abuses can be deterred if the public has a way to audit access to the data stored specifically on them,” Ostrovskiy, the private investigator, said. “Responsible data providers will create responsible end users. Private industry needs big data to help solve problems such as fraud and private industry is much more responsible when they know the public is watching.”

DRN’s statement added, “DRN’s data includes a photograph of a license plate and the date, time and location the photograph was taken. It does not contain any personally identifiable information. DRN products are built with robust reporting and auditing capabilities to ensure transparency at the organization level into usage and compliance with state and federal laws, contractual obligations and internal policies.”

But armed with the license plate, an investigator or other third party could also use a different service to search for the name and address of who the vehicle is registered to. As Motherboard recently reported, Departments of Motor Vehicles (DMVs) are making tens of millions of dollars selling drivers’ names, addresses, and other personal information to an array of industries.

“A powerful tool can be abused and such abuses would infringe on the privacy of Americans.”

DRN’s legal argument for its collection is that the company is automating a task that has been done manually for years—capturing publicly available information.

“Because the camera is photographing license plates in public locations visible for all to see, there is no expectation of privacy in the data we collect,” the contract and various pieces of DRN marketing material read.

Critics say that taking photos and automatically uploading and parsing them at this scale qualitatively creates something to be concerned about.

“I think that argument is a serious understatement of the magnitude of the privacy invasion that this kind of technological advance enables,” Nate Wessler, a staff attorney from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), said in a phone call.

Although public photography is generally legal under the First Amendment and there has been some pushback against private collection in a few states, lawmakers haven’t fully grappled with the ramifications of turning plate photos into a persistent, searchable database that provides a map of millions of peoples’ lives.

“It’s one thing to have had private investigators be able to happen upon somebody’s car parked in their driveway or parked on the street,” Wessler said. “But what ths technology enables is creating a highly accurate digital dossier of the sum total of a person’s movements over time.”

In 2014, Arkansas banned the collection of license plate data by private entities while allowing law enforcement to continue using the technology. DRN pushed back, saying the law violates their First Amendment rights. DRN also contested a Utah law that banned private collection; the company dropped the suit after the state amended that law.

Beyond the collection, there is also the issue of accessing the data. In a recent filing in the Supreme Judicial Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the ACLU and the EFF weighed in on a case involving the technology. In that case, police used license plate data to track an alleged drug trafficker driving back and forth across bridges.

“The District Attorney suggests that these actions do not require a warrant because ‘it is simply unreasonable for any person to believe that their public conduct should remain private from observation in today’s society, where there is a significant amount of video surveillance,’” ACLU and EFF lawyers wrote. “Yet this Orwellian outcome is exactly what [article] 14 and the Fourth Amendment are meant to protect against.” That is, not subject to unreasonable searches and seizures. (The ACLU, EFF, and other lawyers argue in the filing that looking up historical location data collected by license plate readers should require a warrant.)

But one legal issue with industry use of license plate data is that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to non-government entities—a private investigator, or a repo man, or an insurance company does not need a warrant to search for someone’s movements over years; they just need to pay to access the DRN system, or find someone willing to share or leverage their access, like Motherboard did.

Jeramie D. Scott, senior counsel at privacy activist group EPIC, wrote in an email, “License plate readers have been used to create a mass surveillance system that has collected and aggregated billions of license plate records connected to millions of people. This kind of indiscriminate surveillance deserves more scrutiny as it undermines privacy and civil liberties and sets a bad precedent by implying that everything exposed to the public can be collected, aggregated, and analyzed for profit.”

He added, “Although there is a lesser expectation of privacy in the public that doesn’t mean there is no expectation of privacy.”

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.