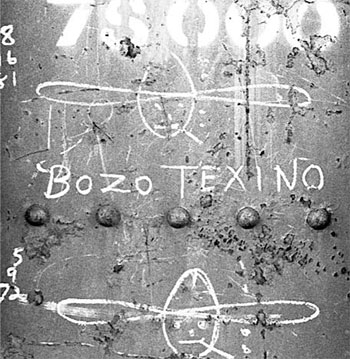

Filmmaker and photographer Bill Daniel documents the graffiti that hobos write on freight trains. Do you do anything anywhere near as old-timey as that? For 16 years, ol’ Bill has sniffed the decaying trail of the character Bozo Texino, a simple line drawing of a pipe-smoking cowboy streaked on boxcars for so many decades that its originator couldn’t possibly still be alive—or could he?

Bill’s research resulted in a movie called Who Is Bozo Texino?, the making of which spawned so much text-based info that he recently released an accompanying book, Mostly True (Microcosm Publishing), which is laid out in the confusing but nonetheless totally cool form of a serial zine that was supposedly printed in 1908. It’s an anthology of tramp graffiti, quasi-literate rants ’n’ raves from crusties and die-hard train hoppers and pissed-off rail workers, and folklore lexicography distinguishing the differences between, say, a poke-out vagabond and a bobo. It has so much of the charm and flair of the early Industrial Revolution that your fingers feel sooty after reading it.

I caught up with Bill as he was trying, so desperately trying, to hightail it out of town on a 6,000-mile-plus tour from his house in Braddock, Pennsylvania, to Canada, then down the West Coast and back. He used to project his film on what he’d dubbed his Sail Van, an orange beast of a vehicle that looks like at least one former owner used it to snatch children. It was outfitted with a ship’s mast and actual sails, but it had to be retired due to its petrol-guzzling infrastructure. When we met, Daniel was working on making a whole new Sail Van. Due to, as he put it, a “relentless series of poor decisions,” he was several days late and already had to cancel a few shows. Then I fucked up his plans a little bit more by making him sit down and talk about them.

Vice: How long has it been since you’ve had this house?

Bill Daniel: Since January. Before this I was chronically—I wouldn’t say homeless… I was, um, scrounging. Before this I had a warehouse in Portland for $250 a month.

I imagined you being a lot more transient.

All my stuff is out of California and out of Oregon, but I still have stuff in Texas and Louisiana.

And you’ve been following tramps for how long?

That project started in the 80s just from being turned on by graffiti on the freights. But you know it wasn’t just hobos, the graffiti was also done by rail workers.

I like that Mostly True busts myths while still playing into them. There’s nothing outright explanatory, it’s just something that as a reader you figure out as you notice cross-references in the articles.

I can’t give you a straight response here but I can say it has to do with the relationship between content and form. An easy way to deal with that is to find an object metaphor or something to pantomime.

Hence an old-timey zine.

Yeah.

Has your book wrapped up this long, obsessive project, or is it a lifelong thing that you think is never going to end?

I sort of wish it could end. The book was part of that goal. But it’s fascinating, the book brought up all these other leads. A month after it was out I got a letter from a grandnephew of J.H. McKinley, the guy who initially drew Bozo Texino. I had no contact with him before. Ten years ago I’d tracked some people down who knew people who knew him in San Antonio, but I lost the thread because I’m underfunded and transitory and have a short attention span. When I got this letter, I happened to be driving from Louisiana back to Braddock and he was on the way. So I went to the cousin’s house in the countryside in Kentucky and stayed with him, and he brought out this shoebox full of his great-uncle’s ephemera. Early drawings when Bozo Texino was still evolving, other tags that he did, photos of him. So there could easily be a whole other chapter. And I’m always getting these emails too. One came from a rail worker who in the late 70s was making Bozo Texino and Colossus of Roads t-shirts. I don’t know, the classic documentarian will hit and run with these serial relationships, one intense thing after another, you go and get the story and move on. I don’t really have that kind of killer instinct.

What kind of instinct do you have?

What kind of instinct do you have?

I want to participate in culture.

What’s your latest project?

It’s called Sunset Scavenger. It’s kind of a catch-all for what I’m doing these days, all the stuff that’s projected on the van—footage of Katrina in New Orleans, desert rats, and houseboats. Some pretty notable beatnik poets and painters were living on barges across the Golden Gate in the 40s. But after the Summer of Love, when the whole thing melted down, a bunch of people scattered and some went to Sausalito and built houseboats. An amazing culture started there, like these hippie houseboats. These people are called anchor-outs because they live on a boat but they’re not tied to a dock. People who live on boats and live next to a dock are totally bourgeois.

So Sunset Scavenger isn’t a narrative but it has a theme?

Yeah, the end of the oil age. For a prototype of Sunset Scavenger I turned what looked like a homeless person’s van into Noah’s Ark, with two projectors screening my footage. I was relating M. King Hubbert, the guy who invented the whole curve and science of peak oil, to a street preacher or to Noah, this person who has knowledge that the end is coming. And no one listens to him because they think he’s a crazy person. However, that person happens to be right. The end is not going to be nice and you better prepare.

Prepare how?

By living on a boat!

See, to me this taps the same point of interest as all the other stuff you’ve done. You’re into transient culture that is somehow linked with transportation. What is it? Where does it come from?

I love cars and bicycles; riding lawn mowers fascinate me. I have more books on boat building than I do on filmmaking. I guess it’s an adolescent male fixation. I really have a nesting urge that I’m starting to feel as time goes on and that’s what’s great about having this house.

Even if it’s not a lifestyle you’re pursuing, there’s clearly something inherently appealing to you.

People who live without jobs or without normal domestic structures have to improvise. They’re artists. Like when people take a school bus and turn it into a house. They’re way more about domesticity than travel. Sure, it’s mobile but all the love and ingenuity is how to turn it into a home. It’s like, “Oh, why don’t you just get a house? They already make ’em. The bathrooms work and the kitchens are spacious.” No. These people are trying to build something that’s readily available in straight culture but trying to build it within their own parameters of poverty or mental illness or social outcast-ness. Are they running from society? Within every individual it’s a different mix of push and pull. Repel from society because you can’t get along with people, or you’re a drug addict. Or pull toward this other life because you have other aspirations—you don’t really care for a big sink. When you have a big sink, it fills up with more dishes. If you have one bowl, you wash it and it’s always clean.

More

From VICE

-

(Rendering via Chinnachart Martmoh / Getty Images) -

(Photo by Jacqueline Anders / Getty Images) -

Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images for Cit -

Screenshot: Blizzard Entertainment