We have a certain image of Victorian womanhood: corsets, fainting couches, a devotion to needlework. It’s true that ladies of the late 1800s were experts in embroidery. But in the back pages of magazines like Home Needlework Journal, Needlecraft, and Modern Priscilla were ads for a Victorian lady’s second favorite hobby: furtive masturbation.

The advent of at-home electricity made the personal vibrator a reality as upper- and middle-class women had been going to their doctors to get off for centuries. Finally, the Industrial Revolution gave women the power to come in the privacy of their own homes. “The first home appliance to be electrified was the sewing machine in 1889,” writes Rachel Maines in her groundbreaking work, The Technology of Orgasm: “Hysteria,” the Vibrator, and Women’s Satisfaction. According to Maines, the electric vibrator was the fifth home electronic ever invented. It “preceded the electric vacuum cleaner by some nine years, the electric iron by ten, and the electric frying pan by more than a decade, possibly reflecting consumer priorities.”

Videos by VICE

So why is our conception of pre-sexual revolution women so vacuum-heavy and vibrator-light? Because to those wacky Victorians, stimulating the clitoris wasn’t masturbating—it wasn’t even sexual. Clitoral stimulation was the palliative cure for a disease. British physician Havelock Ellis’ 1913 work “The Sexual Impulse in Women” estimated that nearly 75 percent of women suffered from “hysteria,” a disease whose symptoms ranged from headaches to epileptic fits to coarse language. Nearly any behavior a woman demonstrated could be construed as hysteria. The number one cure—since the disease’s invention in ancient Greece—was pelvic massage.

Women in the Victorian era weren’t supposed to be able to feel sexual desire, so hysteria became a disease completely removed from sex. They even renamed the orgasm: If a woman became flushed and happy from her pelvic massage, she was said to have underwent a “hysterical paroxysm.” According to Maines, doctors surrounded themselves in “the comforting belief that only penetration was sexually stimulating to women. Thus the speculum and the tampon were originally more controversial in medical circles than was the vibrator.” If a woman desired her clitoris to be stimulated, she was clearly sick with “hysteria,” or so the theory went. And the only cure was to stimulate that clitoris until she didn’t want it to be stimulated anymore. Of course, this cure only worked for so long, and hysterics were lucrative repeat customers.

Ancient Greek physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia called the uterus “an animal within an animal.” He theorized that the womb, if left to its own devices, was prone to going walkabout and strangling the woman from the inside: It needed to be lured back into place with sweet-smelling oils. These oils happened to be applied on and around the clit in a vigorous manner, which likely induced a highly restorative effect for the woman.

Read more: The Racist and Sexist History of Keeping Birth Control Side Effects Secret

The reason behind hysteria changed over the millennia—from wandering womb in ancient times to demonic possession in the Middle Ages. Of course women are more easily possessed; the vagina is an entry point for demons like the exhaust port on the Death Star. Doctors recommended marriage, frequent horseback rides, or getting fingerblasted by a midwife to cure the ailment, according to Maines. By the Victorian era, the cause of hysteria was thought to be modern society and all its demands on fragile womanhood. “In the Victorian period, doctors attributed hysteria to the dangerous behaviors of intellectual women,” writes Greer Theus of Washington and Lee University. All these foot-powered sewing machines and increased literacy rates were tearing women’s delicate minds to shreds. Luckily there had also been advancements in the treatment of hysteria: the water cure, aka the pelvic douche.

Instead of revving up the vibrators, doctors began aiming fire hoses at fire crotches. Pelvic douches, which aimed a jet of water at the inner thighs, were installed in mineral baths all over Europe and America in the mid-1800’s. Women loved them and flocked to the spa towns where such a cure was provided. R.J. Lane, who wrote about his experiences at a spa in England, said men were somewhat fearful of the pelvic douche, but women were “frequently known, on coming out of the douche, to declare that they feel as much elation and buoyancy of spirits, as if they had been drinking champagne.”

With hands cramped and fingers fatigued, doctors loathed treating hysteria. “Physicians seem to have been no more eager to take on the task of producing orgasm in women than were the sexual partners who sent them there for therapy,” writes Maines. Any means of speeding up the hysterical paroxysm was eagerly sought. The first mechanized vibrator used a hand crank. And before cities started metering water usage, there was a brief vogue for home vibrators powered by a miniature water wheel that hooked up to a sink.

But the real game changer was the steam-powered vibrator.

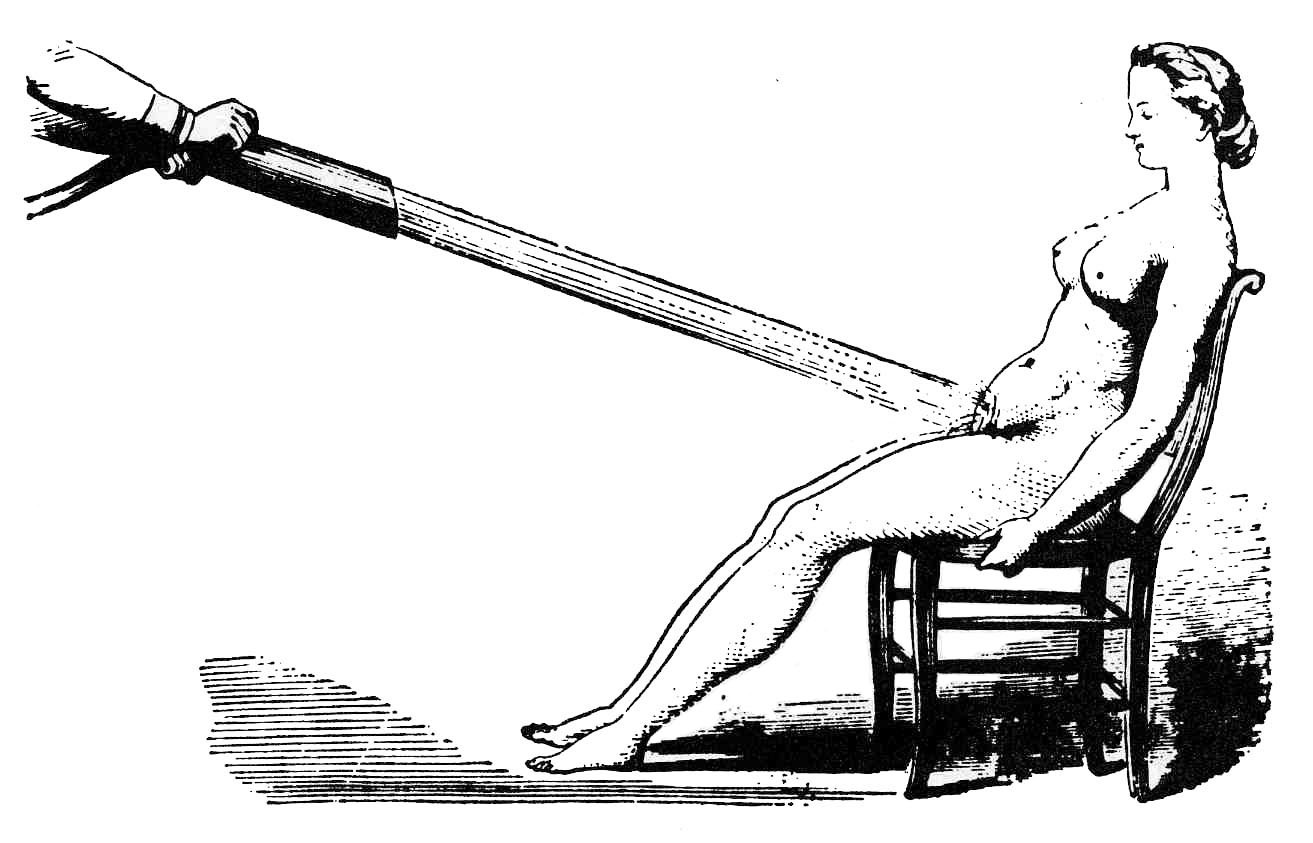

An American doctor named George Taylor patented the “Manipulator” in 1869. Patients sat on a padded table with a vibrating sphere in the center. “His principal markets were spas and physicians with a sufficiently large physical therapy practice to justify the expense of a large, heavy, and cumbersome instrument,” writes Maines.

Eventually, doctors grew weary of shoveling coal into the engines of their vibrators. Mortimer Granville invented the first battery-powered vibrator in the early 1880’s, although he made it explicitly clear that his device was not to be used on the clitoris: “I have avoided, and shall continue to avoid, the treatment of women by percussion, simply because I do not want to be hoodwinked, and help to mislead others, by the vagaries of the hysterical state or the characteristic phenomena of mimetic disease,” he wrote in 1883.

Rather than faking orgasms, Granville thought women were faking a disease in order to have orgasms.

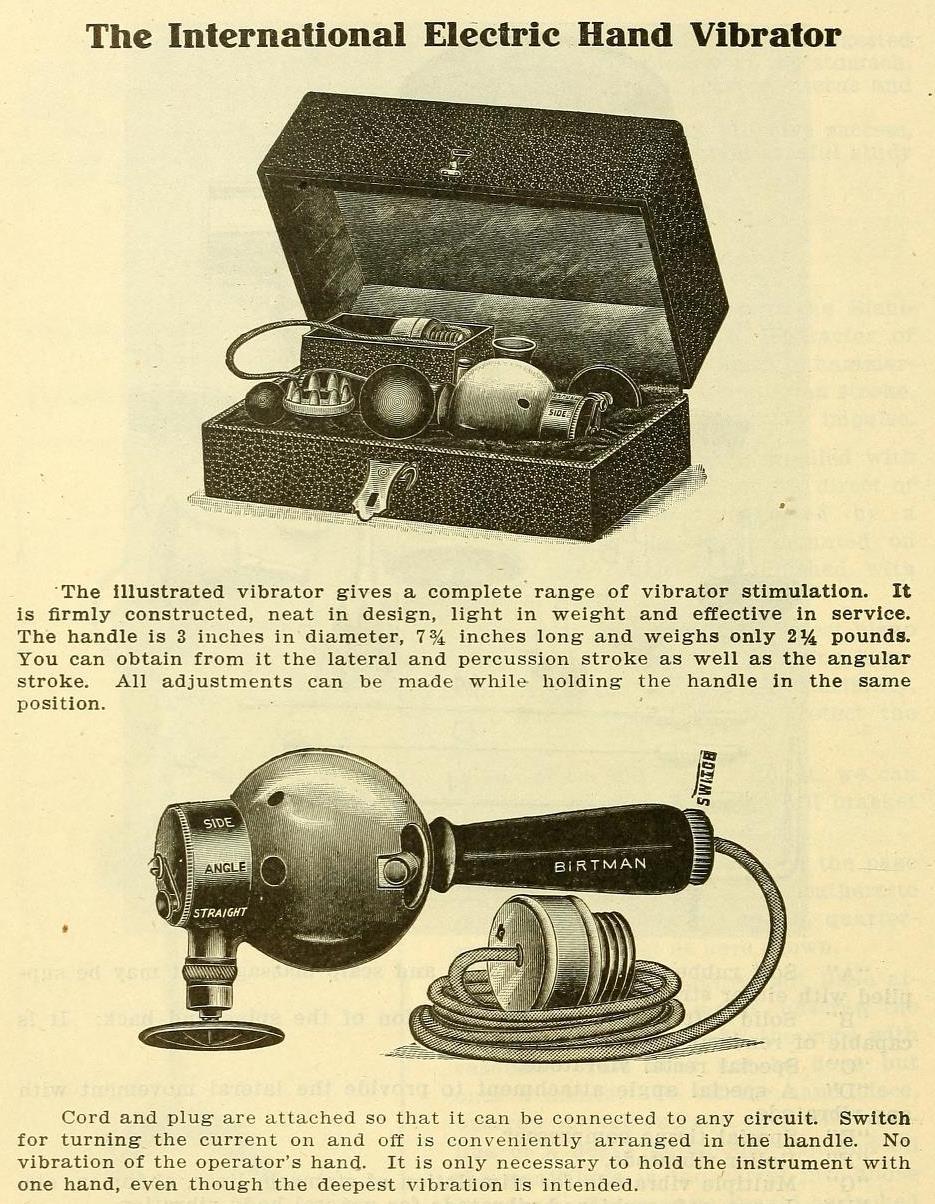

The battery in Granville’s vibrator weighed 40 pounds, but was ostensibly portable. As the turn of the century approached, batteries shrunk in size and women began purchasing vibrators for use in their own home. A 1918 Sears catalog advertised a home motor with several attachments—one attachment was for a vibrator, but the motor could be hooked up to attachments for “churning, mixing, beating, grinding, buffing, and operating a fan” as well, writes Maines.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

Vibrators were advertised prominently in ladies’ magazines until the 1920s, according to sex toy outlet Good Vibrations. The Antique Vibrator Museum notes that “as vibrators began appearing in stag films of the 1920s, it became difficult to ignore their sexual function. Probably as a result, advertisements for vibrators gradually disappeared from respectable publications.” According to Maines, the sex toy industry really took off in the 1980s, and vibrators became a normal part of everyday life. At long last, the device’s time in the spotlight had finally come.